Pterodactyls, with their leathery wings and prehistoric appearance, have captivated our imagination for generations. From their dramatic appearances in films like Jurassic Park to their prominent place in museum displays, these flying reptiles are often grouped with dinosaurs in popular culture. But is this classification scientifically accurate? Many people assume that any large, extinct reptile from the Mesozoic Era must be a dinosaur, but the reality is more complex and fascinating. This article explores the true classification of pterodactyls, their relationship to dinosaurs, and why this distinction matters in our understanding of prehistoric life.

The Common Misconception About Pterodactyls

When most people think of dinosaurs, images of Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, and perhaps flying pterodactyls immediately come to mind. This widespread association stems largely from how prehistoric creatures are portrayed in popular media and even some educational contexts. Movies, books, and toys frequently lump pterodactyls together with dinosaurs, creating a persistent misconception that has proven difficult to correct. Even museum gift shops sometimes sell pterodactyl models in their “dinosaur” collection, further cementing this inaccurate connection. This confusion is understandable given that these creatures lived during the same periods and their fossilized remains are often displayed together in paleontological classification, pterodactyls belong to an entirely different taxonomic group than dinosaurs, despite their concurrent existence during the Mesozoic Era.

Defining What Makes a Dinosaur

To understand why pterodactyls aren’t dinosaurs, we must first clarify what constitutes a dinosaur in scientific terms. Dinosaurs belonclade Dinosauria, which is defined by specific anatomical features. Among these defining characteristics are a hole in the hip socket and limbs positioned directly beneath the body, creating an upright stance rather than the sprawling posture seen in many other reptiles. Dinosaurs also possess distinctive vertebral features and specialized ankle bones that set them apart from other reptilian groups. Additionally, all dinosaurs are strictly terrestrial animals that evolved from ground-dwelling ancestors. This terrestrial origin is crucial to the definition – true dinosaurs never evolved from flying or swimming ancestors, though some dinosaur lineages later adapted to these niches. These specific anatomical traits create a clear boundary around what can scientifically be classified as a dinosaur.

The Proper Classification of Pterodactyls

Pterodactyls, more accurately called pterosaurs (with Pterodactylus being just one genus among many pterosaurs), belong to the order Pterosauria. This group represents the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight, achieving this remarkable feat millions of years before birds. Pterosaurs are part of the larger group Archosauria, which also includes dinosaurs, crocodilians, and their extinct relatives. Within Archosauria, pterosaurs form their distinct branch that evolved separately from the lineage that produces dinosaurs. The earliest pterosaurs appeared in the Late Triassic period, around 228 million years ago, and the group continued to diversify and thrive until their extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period, approximately 66 million years ago. Their classification as a separate order reflects their unique evolutionary history and specialized adaptations for flight, which differ significantly from those found in any dinosaur group.

Anatomical Differences Between Pterosaurs and Dinosaurs

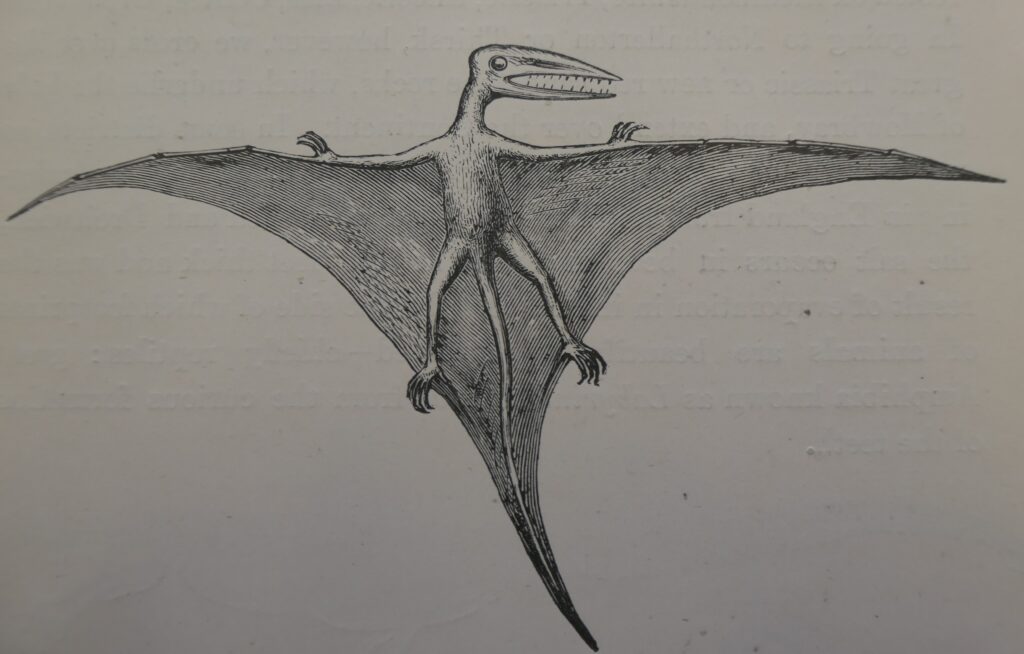

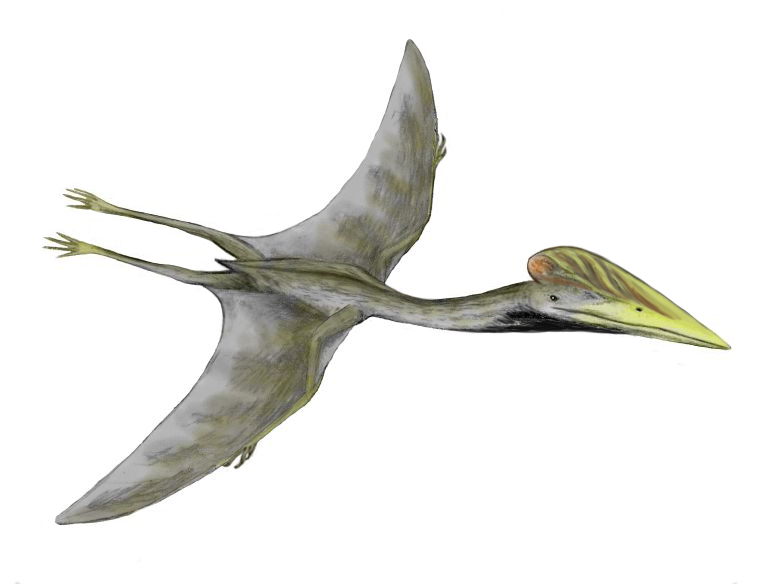

Pterosaurs possessed several distinctive anatomical features that differentiated them from dinosaurs. Most notably, pterosaurs differentiated their limbs with an elongated fourth finger that supported a wing membrane made of skin, muscle, and other tissues. This unique wing structure is entirely different from the feathered wings that evolved independently in some dinosaur lineages. Pterosaur skulls were often specialized with crests, elongated snouts, or other adaptations related to their diverse feeding strategies. Their bones were hollow and thin-walled, containing air spaces (pneumatic bones) that reduced weight for flight efficiency – a convergent adaptation also seen in birds but evolved independently. Perhaps most importantly from a classification standpoint, pterosaurs lacked the distinctive hip structure that defines all dinosaurs. Their ankle joints and pelvis configuration were structured differently, reflecting their separate evolutionary pathway and adaptation to an aerial rather than terrestrial lifestyle.

The Evolution of Pterosaurs

Pterosaurs evolved from small, likely terrestrial reptiles during the Triassic period, developing along a separate evolutionary path from dinosaurs. Their earliest ancestors were probably agile, tree-dwelling reptiles that initially evolved membranes between their limbs for gliding, similar to modern flying squirrels or colugos. Over millions of years, these proto-pterosaurs refined their anatomy for active, powered flight, resulting in the diverse pterosaur lineages we know from the fossil record. Early pterosaurs like Eudimorphodon and Dimorphodon were relatively small, with wingspans of just a few feet, but retained primitive features like teeth and long tails. As pterosaur evolution progressed through the Jurassic and into the Cretaceous periods, they diversified into numerous specialized forms. Some developed into massive creatures like Quetzalcoatlus, with wingspans approaching 36 feet, while others evolved specialized features for fishing, fruit-eating, or even filter-feeding. This evolutionary history shows a distinct trajectory separate from dinosaur evolution, despite occurring during the same geological timeframe.

The Closest Dinosaur Relatives to Pterosaurs

While pterosaurs are not dinosaurs, they do share a common ancestry with them in the deeper past. Both groups belong to the larger clade Archosauria, which emerged in the early Triassic period following the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event. This archosaur clade split into two major branches: the Pseudosuchia (which led to modern crocodilians) and the Avemetatarsalia (which includes pterosaurs and dinosaurs). Within Avemetatarsalia, pterosaurs represent one early offshoot, while dinosaurs represent another. The last common ancestor of pterosaurs and dinosaurs lived approximately 245 million years ago – a small, likely bipedal reptile that possessed features common to early archosaurs. Some of the earliest dinosaurs, like Herrerasaurus and Eoraptor from the late Triassic period, would represent the closest dinosaur relatives to pterosaurs, though they still belonged to entirely separate evolutionary lineages by that point. This relationship makes pterosaurs more like dinosaurs’ cousins rather than members of the dinosaur family.

Flying Dinosaurs: Birds and Their Relationship to Pterosaurs

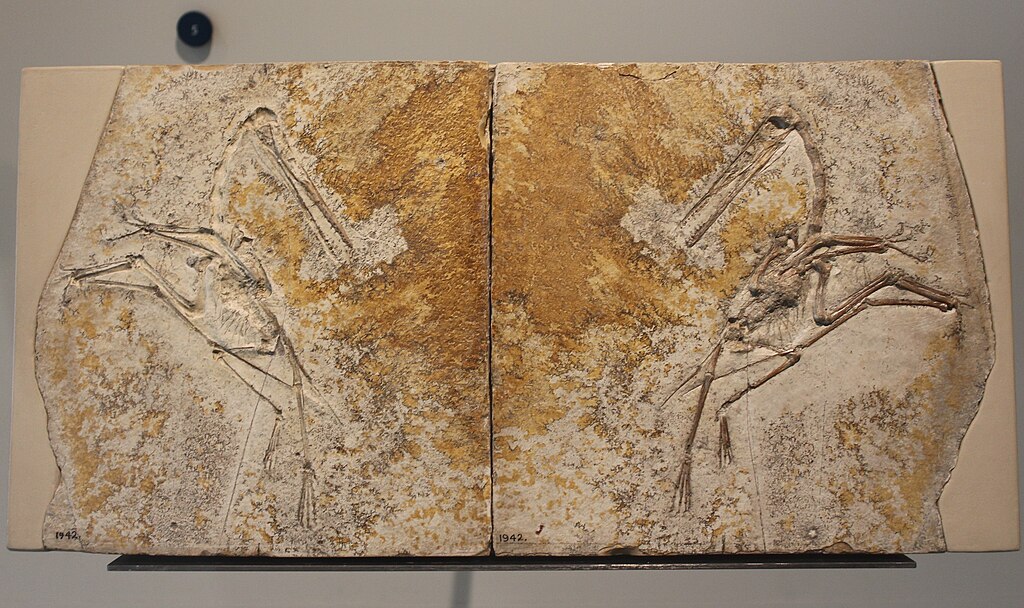

When discussing flying prehistoric creatures, it’s important to clarify that there actually were flying dinosaurs, but they weren’t pterosaurs. Birds (Aves) evolved from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, with Archaeopteryx often cited as an important transitional fossil demonstrating this evolutionary link. Unlike pterosaurs, birds are genuine dinosaurs, specifically part of the maniraptoran theropod lineage that includes velociraptors and other dromaeosaurs. The flight capabilities of birds and pterosaurs represent a remarkable case of convergent evolution – two distantly related groups independently evolving similar adaptations (powered flight) in response to similar selective pressures. Birds developed wings from modified forelimbs covered with feathers, while pterosaurs evolved their wing structure from an elongated finger supporting a membrane. These different anatomical solutions to the challenge of flight highlight their separate evolutionary origins. Modern birds are technically living dinosaurs, but they share no direct ancestral relationship with pterosaurs beyond their common archosaur heritage.

Pterosaur Diversity and Notable Species

The pterosaur group encompassed remarkable diversity throughout its 160-million-year existence, with over 200 known species representing various adaptations and ecological niches. The pterosaur family tree includes the early, long-tailed rhamphorhynchoids like Rhamphorhynchus, which retained primitive features including teeth and extended tails that often ended in distinctive, vaned-like structures. Later pterodactyloids, including the namesake Pterodactylus, evolved shorter tails and diverse skull morphologies adapted to specialized diets. Among the most impressive pterosaurs were the azhdarchids, including Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx, which rank among the largest flying animals ever to exist, with wingspans exceeding 30 feet and heights comparable to giraffes when standing. Other notable pterosaurs include the filter-feeding Pterodaustro with its hundreds of bristle-like teeth for straining small organisms from water, the crested Pteranodon known for its striking backward-pointing cranial crest, and the unusual Dsungaripterus with its upturned, heavy beak specialized for crushing hard-shelled prey. This diversity demonstrates how pterosaurs exploited numerous ecological opportunities despite being separate from dinosaurs.

Living Alongside Dinosaurs: Ecological Relationships

Throughout the Mesozoic Era, pterosaurs and dinosaurs coexisted in diverse ecosystems, each group occupying different niches while occasionally competing for resources. Pterosaurs dominated the skies as the primary large flying vertebrates for most of this period, though they eventually shared this aerial domain with early birds during the late Jurassic and Cretaceous. In coastal environments, pterosaurs like Pteranodon soared over waters where mosasaurs and plesiosaurs (also non-dinosaurs) swam, while on land, various dinosaur species dominated terrestrial niches. Some pterosaurs likely fed on small dinosaurs or dinosaur hatchlings, while others may have scavenged from dinosaur carcasses. Competition between pterosaurs and dinosaurs would have been most pronounced in shoreline environments, where fish-eating pterosaurs might have competed with similarly adapted theropod dinosaurs. This ecological partitioning similarly groups thrive simultaneously for millions of years, despite belonging to separate evolutionary lineages. Their concurrent existence and frequent portrayal together in popular media have contributed significantly to the misconception that pterosaurs were dinosaurs.

Extinction Patterns: Different or Similar Fates?

The extinction patterns of pterosaurs and dinosaurs share important similarities but also key differences. Both groups disappeared from the fossil record at the end of the Cretaceous period, approximately 66 million years ago, during the catastrophic mass extinction event typically associated with an asteroid impact at Chicxulub, Mexico. This event dramatically altered global environments through the impact of winter, acid rain, and widespread habitat destruction. However, recent research suggests that pterosaurs may have been declining in diversity for millions of years before the final extinction event, particularly among smaller and medium-sized species. By the late Cretaceous, pterosaur diversity had narrowed significantly, with azhdarchids becoming the dominant group in many ecosystems. In contrast, non-avian dinosaurs appear to have remained highly diverse right until their abrupt extinction. The one critical difference in their extinction patterns lies with birds – the avian dinosaurs survived the mass extinction event while all pterosaur lineages perished. This selective survival of avian dinosaurs but complete extinction of pterosaurs has important implications for understanding the nature of the end-Cretaceous extinction mechanisms.

Why the Distinction Matters to Science

The distinction between pterosaurs and dinosaurs isn’t merely an exercise in taxonomic pedantry but carries significant implications for our understanding of evolution and prehistoric ecosystems. Recognizing pterosaurs as a separate lineage helps scientists accurately trace the independent evolution of flight in vertebrates, which occurred at least three times (in pterosaurs, birds, and bats) through different mechanical solutions. This classification clarity allows paleontologists to better understand convergent evolution – how similar environmental pressures can produce comparable adaptations in unrelated groups. Accurate classification also informs our understanding of extinction patterns and survival strategies, helping explain why certain groups persisted while others perished during mass extinction events. For evolutionary biologists, maintaining clear distinctions between these groups provides crucial insights into the development of major anatomical innovations and the constraints of body plans. Additionally, precise taxonomy helps scientists communicate effectively about fossil discoveries and evolutionary relationships, building a more accurate picture of Earth’s biological history and the complex interrelationships between prehistoric animal groups.

Pterosaurs in Popular Culture: Perpetuating Misconceptions

Popular media has played a significant role in reinforcing the mistaken belief that dinosaurs were dinosaurs. The Jurassic Park and Jurassic World franchises, despite their groundbreaking depictions of dinosaurs, have consistently portrayed pterosaurs alongside dinosaurs without clearly distinguishing between the groups. In the original Jurassic Park novel by Michael Crichton, the pterosaur species Cearadactylus is even housed in the “Pterosaur House” within the dinosaur park, blurring this taxonomic line. Children’s books frequently include pterosaurs in volumes dedicated to dinosaurs, while toy manufacturers regularly include pterosaur figures in dinosaur-themed playsets. Even educational television programs sometimes fail to make this distinction clear, referring to pterosaurs as “flying dinosaurs” for simplicity’s sake. These consistent portrayals have embedded the misconception deeply in public consciousness, making it one of the most persistent errors in popular paleontology. The dramatic, winged appearance of pterosaurs makes them visually compelling additions to prehistoric scenes, but their continued misclassification undermines accurate scientific understanding among general audiences.

Setting the Record Straight: Educational Approaches

Correcting the widespread misconception about pterosaurs requires intentional educational strategies across multiple platforms. Museum exhibits can play a crucial role by clearly labeling pterosaur displays with explicit information about their classification separate from dinosaurs, perhaps in dedicated sections that explain the different groups of Mesozoic reptiles. Science educators in schools should specifically address this common misconception, using it as an opportunity to teach students about taxonomic classification and how evolutionary relationships are determined. Popular science communicators and paleontology experts can highlight this distinction in books, articles, and media appearances, explaining not just that pterosaurs aren’t dinosaurs but why this matters scientifically. Documentary producers should be encouraged to maintain scientific accuracy even when simplifying complex topics for general audiences. Digital resources, including websites and educational apps about prehistoric life, can incorporate clear explanations about pterosaur classification alongside engaging visuals and interactive elements. By consistently reinforcing accurate information across these channels, the persistent myth of pterosaurs as dinosaurs can gradually be corrected in public understanding.

Conclusion

The classification of pterosaurs as distinct from dinosaurs represents an important scientific distinction that goes beyond mere technicalities. While both groups were reptiles that thrived during the Mesozoic Era, they followed separate evolutionary paths from their common archosaur ancestors. Pterosaurs developed specialized adaptations for flight, including membrane wings supported by an elongated fourth finger, while dinosaurs evolved distinct hip structures and upright postures for terrestrial life. Understanding this distinction enriches our appreciation of prehistoric biodiversity and the different evolutionary solutions that emerged in response to environmental pressures. Although popular media continues to blur the line between these fascinating creatures, recognizing pterosaurs as their remarkable group, rather than as dinosaurs, allows us to better appreciate their u,que place in Earth’s evolutionary history. The next time you see a pterosaur soaring across a prehistoric landscape in a movie or museum display, remember: you’re witnessing not a dinosaur, but a different and equally extraordinary branch on the tree of life.