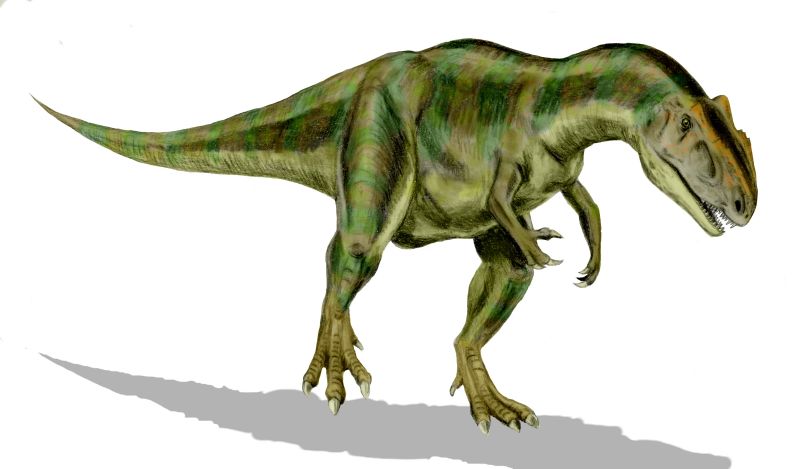

The prehistoric world was filled with fearsome predators, but few were as distinctive as Carnotaurus sastrei. This peculiar theropod dinosaur, whose name translates to “meat-eating bull,” roamed the landscapes of South America during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 72-69 million years ago. With its unique combination of bull-like horns, tiny forelimbs, and a body seemingly built for speed, Carnotaurus has captured the imagination of paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike.

What makes this carnivore particularly special is that it’s known from one of the most complete theropod skeletons ever discovered in the Southern Hemisphere, providing scientists with remarkable insights into its appearance and lifestyle. Let’s delve into the fascinating world of this distinctive predator and uncover what made Carnotaurus such a remarkable creature of its time.

Discovery and Naming: A South American Sensation

Carnotaurus sastrei was discovered in 1984 by paleontologist José Bonaparte during an expedition to Patagonia, Argentina. The find was extraordinary, not just for its completeness but also because it included rare fossilized skin impressions, giving scientists an unprecedented look at the animal’s exterior. The genus name “Carnotaurus” combines the Latin words “carno” (flesh) and “taurus” (bull), referencing both its carnivorous diet and its distinctive bull-like horns.

The species name “sastrei” honors Angel Sastre, the owner of the ranch where the fossil was discovered. This remarkable specimen was described scientifically in 1985, quickly becoming one of the most important dinosaur discoveries from South America. The fossil remains included about 60% of the skeleton, including a nearly complete skull, making Carnotaurus one of the best-known theropods from the Southern Hemisphere.

Physical Characteristics: A Predator Unlike Any Other

Carnotaurus possessed a suite of physical characteristics that set it apart from other theropod dinosaurs. It measured approximately 7.5 to 9 meters (25 to 30 feet) in length and stood about 2.5 meters (8 feet) tall at the hip. Despite this imposing size, it was relatively lightweight for a large theropod, estimated to have weighed between 1.5 and 2 tons. Its most distinctive feature was undoubtedly its skull, adorned with two short, thick horns above the eyes that projected sideways rather than forward.

The skull itself was short, deep, and remarkably robust, with powerful jaw muscles that would have given Carnotaurus a formidable bite. Another unusual feature was its extraordinarily tiny forelimbs, even more reduced than those of the famous Tyrannosaurus rex, with the arms measuring less than 30 cm (12 inches) in length and featuring four stubby fingers. The body of Carnotaurus was streamlined, with powerful hind limbs suggesting it was built for speed rather than power.

The Distinctive Horns: Form and Function

The most iconic feature of Carnotaurus was undoubtedly its pair of thick, bony horns that protruded sideways from above its eyes. These horn cores were approximately 15 cm (6 inches) long and would have been covered with a keratinous sheath in life, potentially making them even larger and more impressive. Unlike the forward-pointing horns of many horned dinosaurs, Carnotaurus’s horns jutted directly sideways, creating a distinctive profile that resembled a bull—hence its name. Paleontologists have debated the function of these unusual structures for decades.

The leading theory suggests they were primarily used in intraspecific competition—males may have engaged in pushing or shoving contests to establish dominance, similar to modern horned mammals. Alternative hypotheses propose they may have served as display structures to attract mates or as species recognition features. Some researchers have even suggested they might have been used as battering rams against prey, though the relatively delicate construction of the skull makes this less likely.

Tiny Arms: The Mystery of Reduced Forelimbs

One of the most puzzling features of Carnotaurus was its extraordinarily tiny forelimbs, which were even more reduced than those of Tyrannosaurus rex. These diminutive arms measured just 25-30 cm (10-12 inches) in length—proportionally smaller than those of any other large theropod. Each arm ended in four small fingers lacking claws, making them essentially useless for grasping prey. This extreme reduction has led paleontologists to conclude that the forelimbs served virtually no practical purpose in the animal’s daily life.

The evolutionary trend toward reduced forelimbs appears in several theropod lineages, suggesting that as the head and jaws took on more functions in hunting and feeding, the arms became increasingly vestigial. Some researchers have proposed that the tiny arms might have played a role in mating behaviors or helped the animal rise from a prone position, though most evidence suggests they were simply evolutionary remnants. The reduced weight of these tiny limbs may have also helped Carnotaurus maintain its center of gravity, potentially enhancing its speed and agility.

Speed and Locomotion: Built for the Chase

Unlike many large theropods that relied on power and strength, Carnotaurus appears to have been built for speed. Its leg bones show proportions similar to those of modern cursorial (running) animals, with long, slender femurs and tibiae that would have enabled swift movement. Biomechanical studies of its skeleton suggest Carnotaurus could have reached speeds of up to 48-56 km/h (30-35 mph), making it one of the fastest large theropods of its time. The animal’s relatively lightweight build further supports this interpretation, as does its narrow body and stiffened tail.

The tail of Carnotaurus was particularly specialized, featuring interlocking vertebral processes that limited lateral movement, effectively turning the tail into a rigid counterbalance during rapid turns and acceleration. This combination of adaptations suggests Carnotaurus was an active pursuit predator rather than an ambush hunter, potentially specializing in chasing down smaller, agile prey across the Patagonian landscapes of the Late Cretaceous.

Skin Impressions: A Rare Paleontological Treasure

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Carnotaurus discovery was the preservation of extensive skin impressions, covering portions of the neck, tail, and sides of the body. These impressions reveal that, unlike many other dinosaurs, Carnotaurus lacked feathers and was instead covered in a mosaic of small, non-overlapping scales measuring 4-5 mm in diameter. Interspersed among these small scales were larger feature scales arranged in rows along the sides of the animal, creating a distinctive pattern. Particularly noteworthy were larger conical scales along the animal’s flanks that may have served as display features.

The skin lacked the osteoderms (bony plates) found in some other theropods, suggesting Carnotaurus had minimal dermal armor. These skin impressions represent one of the most extensive and well-preserved examples of dinosaur integument ever found for a large theropod, providing invaluable insights into the external appearance of these ancient creatures. The pattern and arrangement of scales may have provided camouflage in the animal’s natural habitat or played a role in thermoregulation.

Hunting and Diet: Predatory Strategies

As a medium-sized theropod carnivore, Carnotaurus would have been an active predator in its ecosystem. Its skull structure and dentition provide important clues about its feeding habits. The teeth of Carnotaurus were blade-like and serrated, ideal for slicing through flesh, though they were shorter and less robust than those of some other large theropods. This suggests it may have targeted smaller prey or focused on different parts of carcasses than contemporaneous predators. The unusually strong neck musculature, evidenced by attachment sites on the skull and vertebrae, indicates Carnotaurus could deliver powerful, slashing bites, possibly employing a “bite-and-slice” strategy rather than the bone-crushing tactics of some larger theropods.

Its powerful hind limbs and streamlined build suggest it was capable of pursuing prey at high speeds, potentially specializing in hunting smaller, faster dinosaurs that other large predators might have had difficulty catching. Some paleontologists have proposed that Carnotaurus might have employed its horns in hunting, perhaps to deliver stunning blows to prey, though this remains speculative given the relatively delicate construction of its skull.

Habitat and Environment: Life in Late Cretaceous Patagonia

Carnotaurus inhabited the landscapes of what is now Patagonia, Argentina, during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 72-69 million years ago. During this time, this region of South America experienced a warm, semi-arid climate with seasonal rainfall. The environment consisted of open woodlands and riparian forests along rivers and streams, rather than dense jungle. Fossil evidence from the Auca Mahuevo and La Colonia formations, where Carnotaurus remains have been found, indicates a diverse ecosystem inhabited by a variety of dinosaurs, including titanosaurid sauropods, which may have been potential prey.

Other fauna included small to medium-sized ornithopods, primitive birds, crocodilians, turtles, and various small vertebrates. The geography of Late Cretaceous Patagonia featured floodplains, meandering rivers, and seasonal wetlands, creating a mosaic of habitats that Carnotaurus could exploit. This environment would have provided both open spaces where Carnotaurus could utilize its speed for hunting and vegetated areas that might have served as ambush points.

Evolutionary Relationships: Where Carnotaurus Fits in the Dinosaur Family Tree

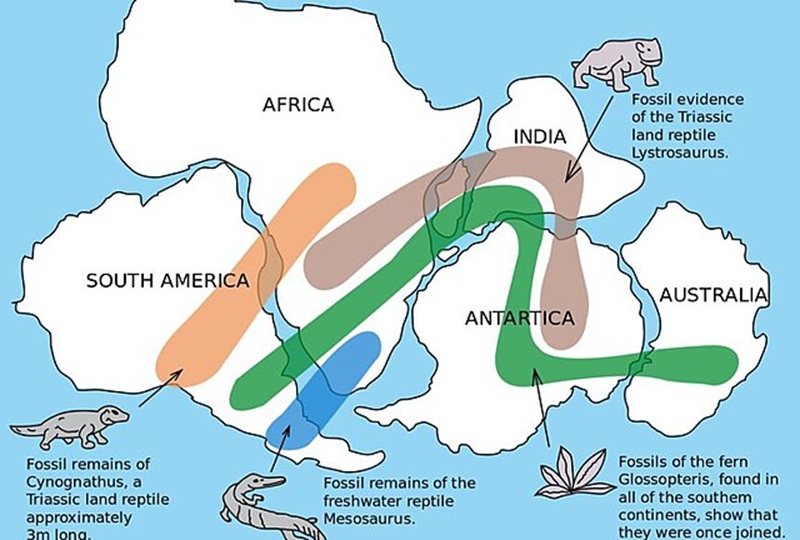

Carnotaurus belongs to the Abelisauridae, a family of ceratosaurian theropods that dominated the predatory niches in the Southern Hemisphere during the Late Cretaceous period. This family is characterized by shortened skulls, reduced forelimbs, and often elaborate cranial ornamentation. Within this family, Carnotaurus is placed in the subfamily Carnotaurinae alongside relatives like Aucasaurus and Majungasaurus. Abelisaurids evolved separately from the tyrannosaurs that dominated Northern Hemisphere ecosystems, representing a case of convergent evolution where different lineages developed similar ecological roles in separate regions.

Carnotaurus represents one of the most specialized members of its family, with its extreme limb reduction and unique horned skull being evolutionary experiments not seen in quite the same form in any other dinosaur. The isolation of South America during much of the Late Cretaceous likely contributed to the distinctive evolutionary path taken by Carnotaurus and its relatives, as they adapted to local environmental conditions and ecological opportunities without competition from other major theropod groups like tyrannosaurs.

Social Behavior: Lone Hunter or Pack Predator?

The social behavior of Carnotaurus remains largely speculative, as no definitive fossil evidence of group behavior has been discovered. However, by examining the animal’s physical adaptations and comparing them to both modern predators and other theropods, paleontologists have developed several hypotheses. The horns of Carnotaurus suggest some form of intraspecific competition or display, indicating these animals likely interacted with members of their own species at least during mating season.

Some researchers have proposed that Carnotaurus might have been a solitary hunter, using its speed to chase down prey that larger, slower theropods might have had difficulty catching. Others suggest it might have engaged in loose social groupings similar to some modern reptilian predators, perhaps cooperating temporarily when taking down larger prey.

The relatively standard brain size for a theropod of its dimensions suggests Carnotaurus wasn’t particularly more or less social than other large predatory dinosaurs. Without direct fossil evidence of multiple individuals preserved together, the question of whether Carnotaurus hunted alone or in groups remains one of the many mysteries surrounding this distinctive dinosaur.

Carnotaurus in Popular Culture: A Distinctive Celebrity Dinosaur

With its distinctive horns and unusual proportions, Carnotaurus has become a popular dinosaur in contemporary media despite being less well-known than icons like Tyrannosaurus or Velociraptor. Its most prominent appearance came in Disney’s 2000 animated film “Dinosaur,” where a pair of Carnotaurus served as the main antagonists, though they were portrayed as larger and more powerful than their real-life counterparts.

Carnotaurus also made a brief but memorable appearance in “Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom” (2018), showcasing its distinctive horned profile to mainstream audiences. In the world of literature, Carnotaurus features in Michael Crichton’s novel “The Lost World,” though it was omitted from the film adaptation. Various documentaries, including several episodes of the BBC’s “Planet Dinosaur,” have featured Carnotaurus, typically highlighting its unusual combination of speed and distinctive horns.

The dinosaur has also become a staple in dinosaur-themed video games, toys, and educational materials, where its unique appearance makes it instantly recognizable even among the crowded field of theropod dinosaurs. This media presence has helped transform Carnotaurus from an obscure South American fossil to one of the more recognizable non-avian dinosaurs in popular culture.

Research Challenges: Working with Limited Fossil Evidence

Despite the remarkable completeness of the original Carnotaurus specimen, paleontologists still face significant challenges in studying this unusual dinosaur. The primary limitation is that only one relatively complete specimen has been discovered, making it difficult to assess variations between individuals or changes that might occur during growth and development. Without multiple specimens of different ages, scientists cannot construct a growth series to understand how juvenile Carnotaurus might have differed from adults or whether sexual dimorphism existed in the species.

Additionally, certain aspects of the skeleton, particularly parts of the hands and feet, are not perfectly preserved, leaving some anatomical details to be inferred rather than directly observed. The delicate nature of the skull, with its distinctive horns, has also presented preservation challenges, leading to ongoing debates about the exact appearance and function of these structures. Despite these limitations, continued research using advanced technologies like CT scanning and biomechanical modeling has allowed paleontologists to extract remarkable amounts of information from the available fossil material, gradually building a more complete picture of this fascinating predator.

Extinction: The End of the Horned Hunter

Carnotaurus disappeared from the fossil record approximately 69 million years ago, well before the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event that wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs around 66 million years ago. This suggests that Carnotaurus and its immediate lineage may have fallen victim to more localized extinction pressures rather than the global catastrophe caused by the Chicxulub asteroid impact. Several factors may have contributed to its disappearance, including changes in the South American climate and ecosystem, competition from other predators, or the evolutionary dead-end of its highly specialized adaptations. The extreme reduction of its forelimbs and unique cranial morphology represent specialized adaptations that may have limited its ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

During the Late Cretaceous, South America was experiencing significant geological and environmental changes as the continent continued to separate from Africa and move toward its modern position. These changes likely altered habitats and prey availability, potentially putting pressure on specialized predators like Carnotaurus. While we may never know exactly why this distinctive predator disappeared, its specialized anatomy provides a fascinating case study in evolutionary experimentation among theropod dinosaurs.

Legacy: What Carnotaurus Teaches Us About Dinosaur Evolution

Carnotaurus stands as a remarkable example of evolutionary specialization, demonstrating how natural selection can produce extreme adaptations in response to specific ecological pressures. Its tiny forelimbs represent one of the most dramatic examples of limb reduction in theropod evolution, while its horned skull showcases how display structures and species recognition features could evolve in predatory dinosaurs. As one of the best-known abelisaurids, Carnotaurus helps illuminate the distinct evolutionary path taken by Southern Hemisphere theropods during the Late Cretaceous, showing how isolated continental faunas could develop their own unique apex predators convergent with but distinct from those on other landmasses.

The discovery of preserved skin impressions with the Carnotaurus skeleton has provided invaluable data about dinosaur integument, challenging earlier assumptions and contributing to our understanding of how these animals appeared in life. Perhaps most importantly, the unique combination of features seen in Carnotaurus—horns, reduced arms, speed-adapted limbs—