Picture this: a world where massive herbivores still roam the African savanna, where flying reptiles soar over pristine coastlines, and where apex predators the size of school buses patrol ancient forests. It sounds like a fantasy, but what if it didn’t have to be? What if humanity had existed alongside the dinosaurs during their final moments 66 million years ago – could we have prevented the most famous extinction event in Earth’s history? While time travel remains firmly in the realm of science fiction, exploring this hypothetical scenario reveals fascinating insights about conservation, extinction, and the delicate balance of life on our planet.

The Asteroid That Changed Everything

The Chicxulub asteroid impact wasn’t just another cosmic event – it was a planet-altering catastrophe that reshaped life on Earth in ways we’re still discovering. When this 6-mile-wide space rock slammed into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula, it released energy equivalent to billions of atomic bombs, instantly vaporizing rock and creating a crater over 90 miles wide.

The immediate aftermath was nothing short of apocalyptic. Massive tsunamis swept across continents, earthquakes shook the globe, and superheated debris rained down like a deadly storm. But the real killer was what came next – a thick cloud of dust and debris that blocked out the sun for months, plunging the planet into a nuclear winter that would make our harshest ice ages look mild.

Could even the most advanced conservation efforts have saved the dinosaurs from this cosmic catastrophe? The sheer scale of destruction suggests that traditional wildlife protection methods would have been utterly useless against such a force of nature.

Early Warning Systems for Extinction

Modern astronomers track potentially hazardous asteroids using sophisticated telescopes and computer models, giving us decades of advance warning for most cosmic threats. If such technology had existed in the late Cretaceous period, dinosaur-era scientists might have spotted the Chicxulub impactor years before it arrived.

With sufficient warning, hypothetical prehistoric conservationists could have implemented emergency protocols to protect key species. Deep underground bunkers, similar to our modern seed vaults, might have housed breeding populations of smaller dinosaur species along with stockpiles of food and water.

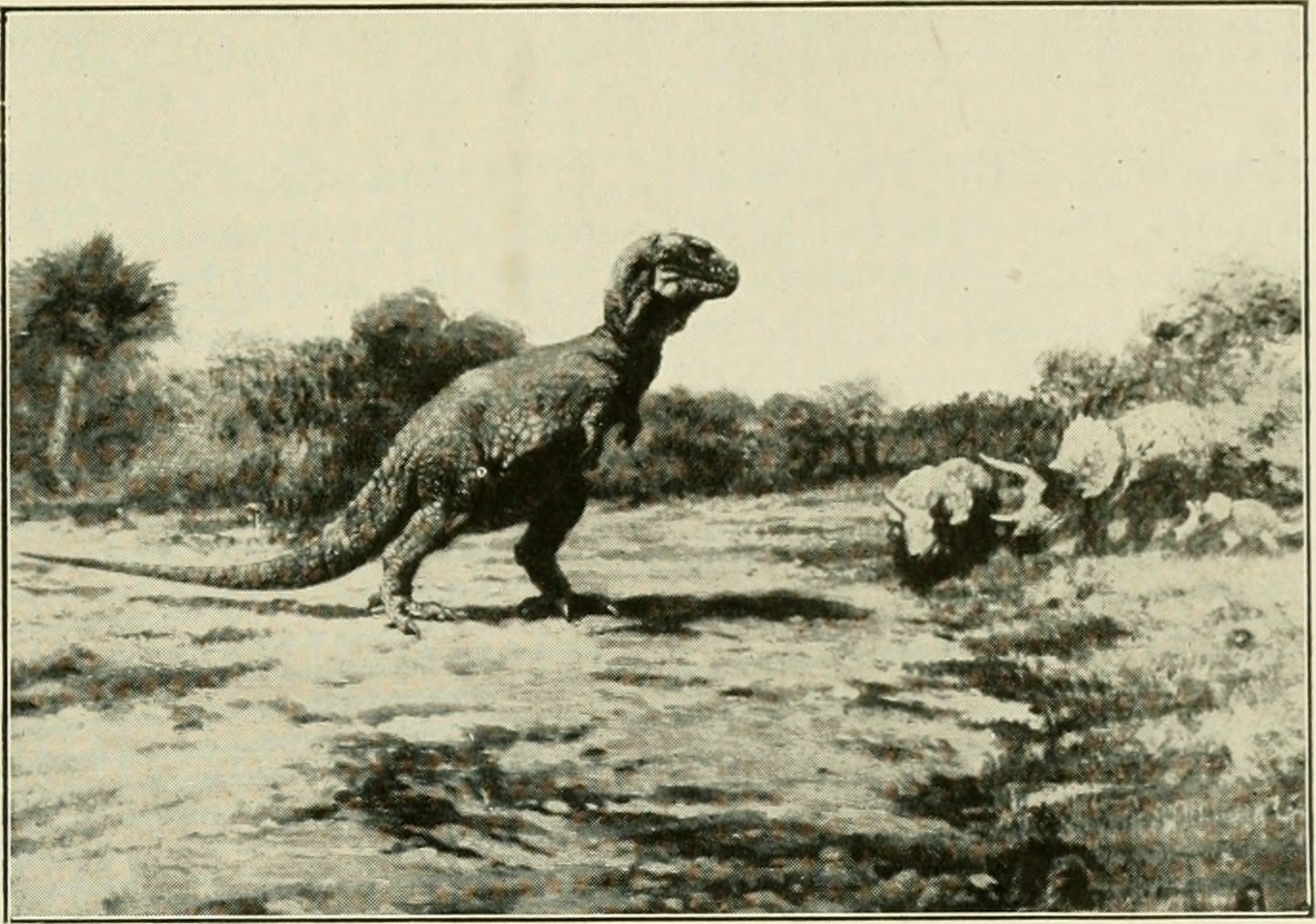

The challenge would have been enormous – how do you relocate a 40-ton Triceratops or convince a territorial Tyrannosaurus rex to enter a protective facility? Even with advance warning, the logistics of saving creatures that size would have tested the limits of any conservation program.

Genetic Rescue Before It Was Too Late

Today’s conservation biologists use genetic tools that would have seemed like magic to earlier generations. DNA banking, artificial insemination, and embryo transfer techniques have saved species from the brink of extinction and could theoretically have been applied to dinosaurs.

Imagine prehistoric geneticists collecting DNA samples from dying dinosaur populations, preserving their genetic material in specialized facilities designed to survive the impact winter. With modern techniques like CRISPR gene editing, scientists could have potentially enhanced dinosaur embryos to survive in the harsh post-impact environment.

The concept of “genetic rescue” – introducing genetic material from healthy populations to struggling ones – might have prevented the genetic bottlenecks that likely contributed to dinosaur extinctions. However, the technology required would have been far beyond what was possible 66 million years ago.

Underground Cities for Giants

The most ambitious conservation project would have involved creating massive underground habitats capable of supporting dinosaur populations through the impact winter. These subterranean refuges would have needed to be engineering marvels, with artificial lighting systems, temperature control, and self-sustaining ecosystems.

Consider the space requirements: a single adult Brontosaurus needed roughly the same amount of food as 40 modern elephants. Underground facilities would have required enormous caverns, sophisticated ventilation systems, and massive food production capabilities to sustain even small populations of large dinosaurs.

The construction challenges alone would have been staggering. Moving excavated material from sites large enough to house dinosaurs would have required technology and coordination on a scale that dwarfs our modern mega-projects. Yet without such facilities, the largest dinosaurs would have had virtually no chance of survival.

The Food Chain Collapse Crisis

Even if conservationists had successfully sheltered dinosaur populations, they would have faced an even greater challenge: reconstructing the complex food webs that sustained these ancient ecosystems. The asteroid impact didn’t just kill dinosaurs – it devastated plant life, collapsed marine ecosystems, and triggered a cascade of extinctions throughout the food chain.

Herbivorous dinosaurs depended on specific plant species that disappeared during the impact winter. Without these food sources, even well-protected dinosaur populations would have slowly starved. Carnivorous species faced their own crisis as prey animals vanished, creating a domino effect that rippled through entire ecosystems.

Modern conservation efforts focus heavily on habitat preservation because protecting individual species without their environments rarely succeeds long-term. Saving the dinosaurs would have required preserving and reconstructing entire prehistoric ecosystems – a task that would have challenged even the most advanced civilization.

Climate Engineering on a Planetary Scale

The impact winter following the Chicxulub asteroid created global climate conditions that were fundamentally incompatible with dinosaur survival. Temperatures plummeted, precipitation patterns shifted dramatically, and the lack of sunlight made photosynthesis nearly impossible for months.

Hypothetical prehistoric conservationists might have attempted climate engineering projects to counteract these effects. Massive greenhouse structures could have maintained warm temperatures for selected habitats, while artificial lighting systems might have kept essential plant species alive during the darkest period.

The scale of such interventions would have required unprecedented cooperation and resources. Imagine coordinating global climate modification efforts while simultaneously managing refugee populations of displaced dinosaurs – it would have been the ultimate test of any civilization’s technological and organizational capabilities.

Marine Sanctuaries for Sea Giants

The oceans suffered tremendously during the mass extinction event, but they also offered some potential refuge from the worst effects of the impact winter. Marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and mosasaurs faced their own conservation challenges, but underwater environments might have provided better protection from the immediate aftermath of the asteroid impact.

Establishing marine protected areas could have given sea-dwelling dinosaurs and marine reptiles a better chance of survival. These sanctuaries would have needed to protect not just the large predators but also the smaller organisms that formed the base of marine food webs.

The challenge would have been maintaining water quality and temperature in a world where normal ocean circulation patterns were disrupted. Massive artificial reef systems might have provided shelter and breeding grounds for surviving marine species, creating pockets of life in otherwise devastated seas.

The Mammal Competition Factor

Even if dinosaurs had survived the initial extinction event, they would have faced intense competition from rapidly evolving mammalian species. Small mammals weathered the crisis better than large reptiles, and in the aftermath, they quickly diversified to fill ecological niches left vacant by dinosaur extinctions.

Conservation efforts would have needed to address this competitive pressure by creating protected spaces where dinosaurs could recover without facing mammalian competitors. Think of it as prehistoric wildlife corridors designed to give dinosaurs room to rebuild their populations.

The irony is striking – the same adaptability that helped mammals survive the extinction event would have made them formidable competitors for recovering dinosaur populations. Successful dinosaur conservation might have required controlling mammalian populations, essentially reversing the natural course of evolution.

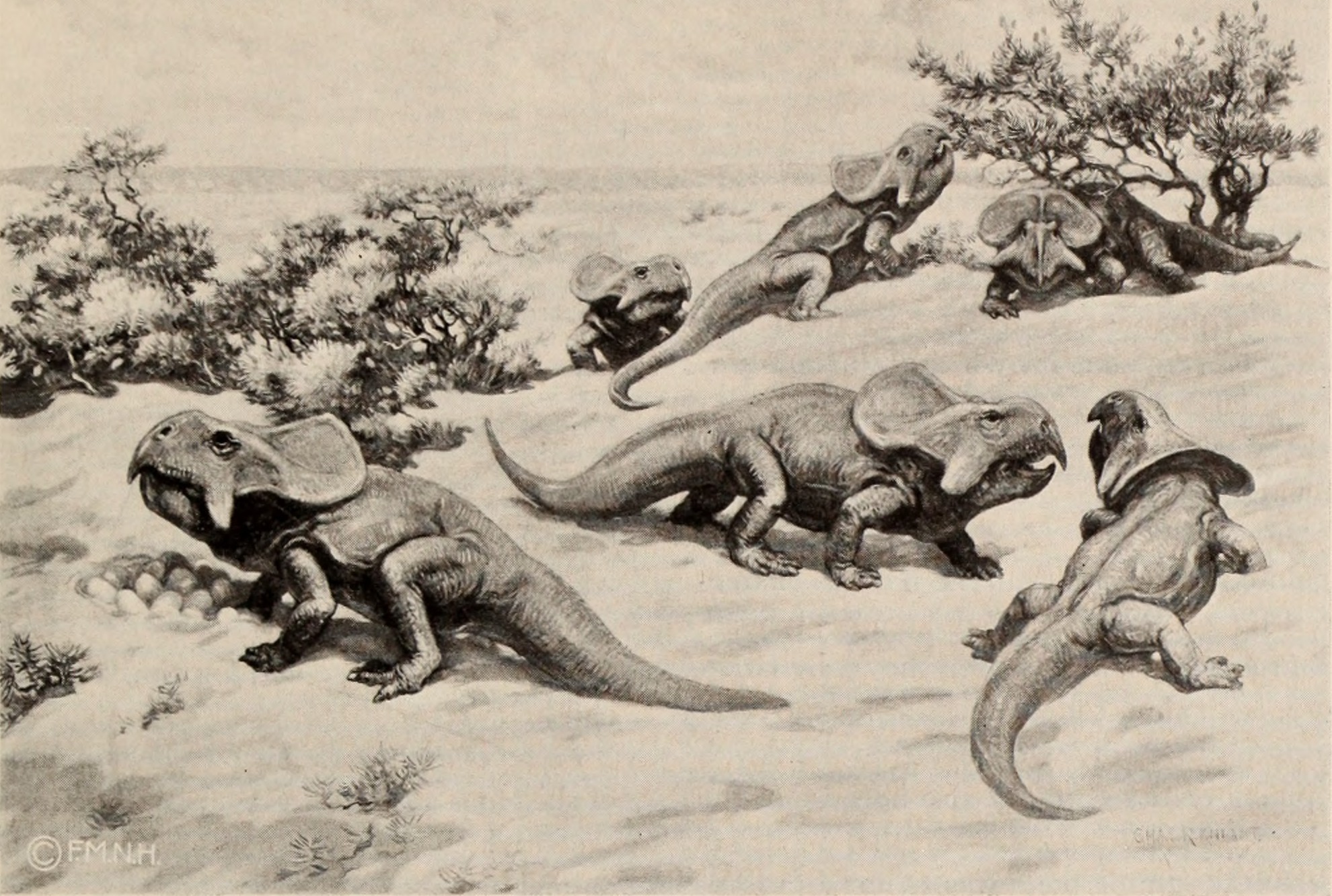

Breeding Programs for Extinct Giants

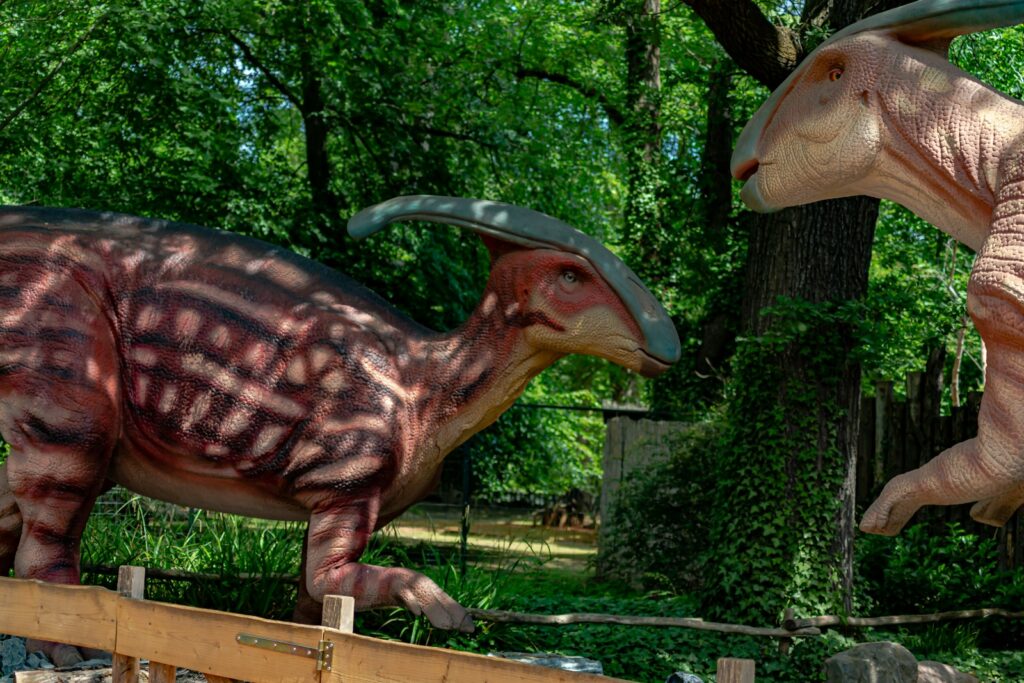

Modern captive breeding programs have brought species back from the brink of extinction, but scaling these efforts to dinosaur-sized animals would have presented unique challenges. Breeding programs for large dinosaurs would have required facilities comparable to modern zoos, but designed for creatures that could weigh as much as ten elephants.

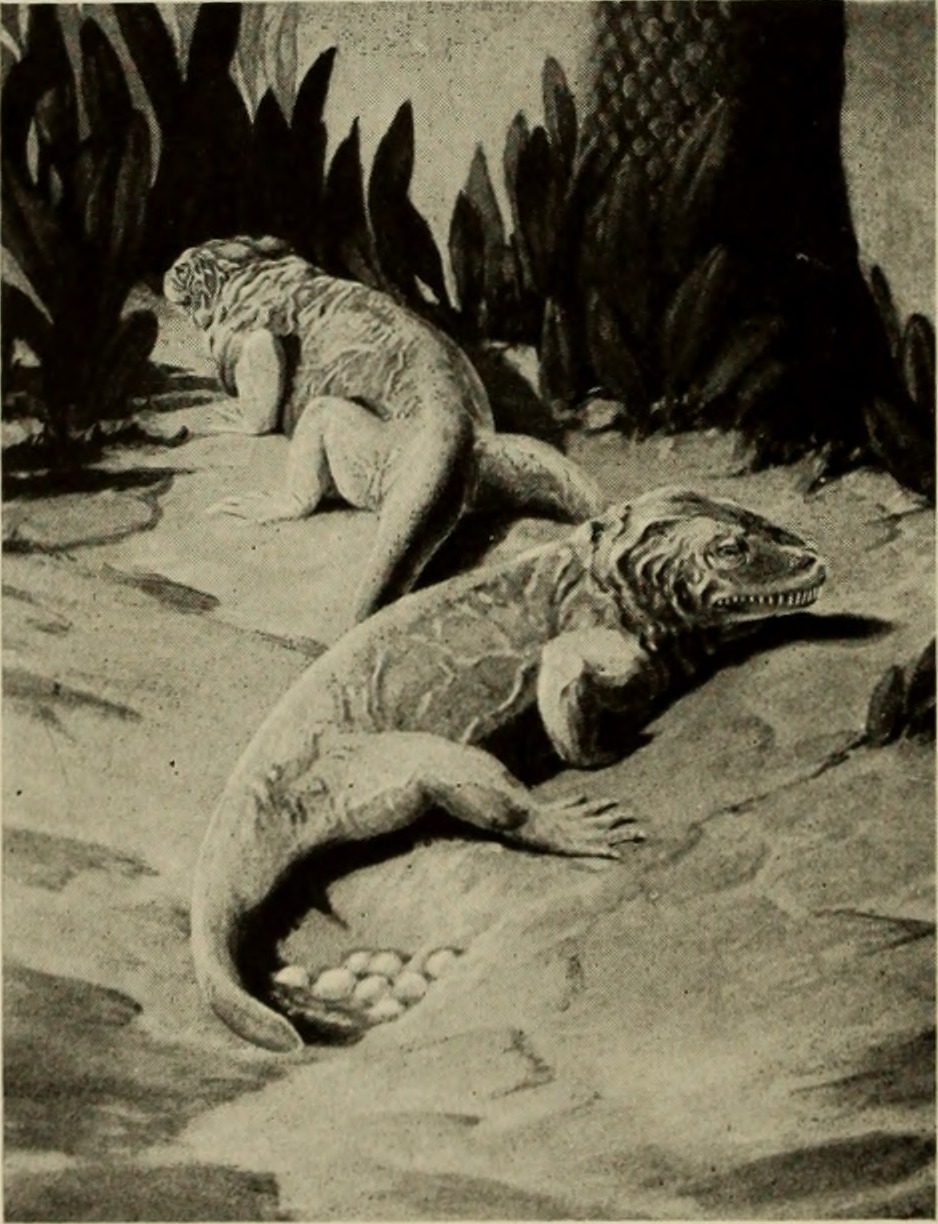

The logistics of dinosaur reproduction would have been staggering. Some sauropods laid eggs the size of footballs, requiring specialized incubation facilities and round-the-clock monitoring. Baby dinosaurs would have needed protection from their own parents, as many species showed little parental care beyond nest-building.

Genetic diversity would have been crucial for long-term success. Maintaining healthy breeding populations would have required careful record-keeping and strategic breeding decisions to prevent inbreeding depression – concepts that modern conservation biology has only recently perfected.

Technology That Could Have Made a Difference

The hypothetical conservation of dinosaurs would have required technology far beyond what existed in the Cretaceous period. Advanced materials science would have been essential for constructing facilities strong enough to contain enormous predators, while biotechnology would have been crucial for maintaining dinosaur health and reproduction.

Climate control systems would have needed to maintain stable temperatures across vast areas, while water purification technology would have been essential for keeping aquatic habitats healthy. Even transportation would have been a challenge – how do you safely move a sick Triceratops to a veterinary facility?

The communication and coordination requirements alone would have demanded sophisticated information networks. Managing conservation efforts across multiple continents would have required real-time data sharing and coordination on a scale that challenges even modern global organizations.

The Human Element in Prehistoric Conservation

Even with perfect technology, dinosaur conservation would have required unprecedented human cooperation and dedication. The scale of the crisis would have demanded that entire civilizations dedicate their resources to saving species that many people might never see in person.

Public support would have been crucial – imagine trying to convince taxpayers to fund massive underground facilities for creatures that had been apex predators just years before. The psychological challenge of coexisting with dinosaurs would have been enormous, especially for species like Tyrannosaurus rex that viewed humans as potential prey.

Cultural and religious considerations would have played a major role in conservation efforts. Different societies might have had varying views on whether dinosaurs deserved salvation, and competing priorities could have undermined global conservation efforts when unity was most needed.

Lessons from Failed Conservation Attempts

History shows us that even well-intentioned conservation efforts can fail spectacularly. The passenger pigeon, once numbering in the billions, went extinct despite last-minute attempts to save the species. These failures offer sobering lessons about the challenges of preventing extinctions once they gain momentum.

Habitat destruction often proves more devastating than direct hunting or natural disasters. Even if dinosaurs had been protected from the immediate effects of the asteroid impact, the long-term environmental changes might have made their survival impossible regardless of human intervention.

The complexity of ecosystem interactions means that saving individual species without preserving their entire ecological context rarely succeeds. This lesson suggests that piecemeal dinosaur conservation efforts would have been doomed from the start – only comprehensive ecosystem preservation could have worked.

Alternative Extinction Scenarios

The asteroid impact wasn’t the only threat dinosaurs faced during the late Cretaceous period. Volcanic activity, climate change, and disease outbreaks all contributed to declining dinosaur populations even before the final catastrophe. These alternative extinction pressures might have been more manageable with proper conservation efforts.

If the asteroid had missed Earth entirely, dinosaurs might have faced a slower extinction process that conservation efforts could have addressed. Disease management, habitat protection, and population monitoring might have been enough to prevent the gradual decline that was already underway.

The multiple stressors affecting dinosaur populations suggest that successful conservation would have required addressing numerous threats simultaneously. This comprehensive approach would have been far more achievable than trying to protect dinosaurs from a planet-killing asteroid impact.

What Modern Conservation Can Learn

While we can’t save the dinosaurs, their hypothetical conservation offers valuable insights for protecting today’s endangered species. The challenges faced by prehistoric conservationists mirror many problems confronting modern wildlife protection efforts – habitat loss, climate change, and human-wildlife conflict remain persistent threats.

The scale of resources required for dinosaur conservation highlights the importance of acting before species reach critical endangerment levels. Prevention is always more effective and less expensive than emergency intervention, whether we’re talking about dinosaurs or modern elephants.

Global cooperation would have been essential for dinosaur conservation, just as it is for protecting today’s migratory species and shared ecosystems. The hypothetical failure to save dinosaurs reminds us that conservation efforts must transcend national boundaries and political differences to succeed.

The question of whether dinosaurs could have been saved ultimately reveals more about human nature than prehistoric biology. While the technological and logistical challenges would have been overwhelming, the real barrier might have been our ability to cooperate on a global scale during a crisis. Today’s conservation efforts face similar challenges – though thankfully on a smaller scale than a planet-killing asteroid. The dinosaurs’ fate reminds us that extinction is forever, making every current conservation success story that much more precious. Perhaps the most important lesson is that we shouldn’t wait for our own asteroid moment to take wildlife protection seriously. What would future civilizations think if they discovered we had the tools to prevent extinctions but chose not to use them?