The ancient world of dinosaurs continues to captivate our imagination, even millions of years after their extinction. While we’ve made remarkable strides in understanding their physical characteristics through fossil evidence, the behavioral aspects of dinosaur lives remain more mysterious. One intriguing question is whether some dinosaur species might have exhibited complex social structures similar to those we observe in modern pack animals like wolves. This article explores the evidence, theories, and scientific reasoning behind the possibility of social dinosaurs, examining what paleontological findings can tell us about dinosaur behavior and social organization.

The Challenge of Understanding Dinosaur Behavior

Reconstructing dinosaur behavior presents unique challenges for paleontologists compared to studying physical characteristics. While bones and fossils provide concrete evidence of size, shape, and physical adaptations, behavior leaves few direct traces in the fossil record. Scientists must rely on indirect evidence such as trackways, nesting sites, and comparisons with modern animals to form theories about dinosaur social structures. This interpretive approach requires careful analysis of multiple lines of evidence and often leads to ongoing scientific debates. Despite these challenges, researchers have developed increasingly sophisticated methods to decode behavioral patterns from the limited evidence available, allowing us to glimpse aspects of dinosaur social life that were once thought impossible to determine.

Evidence from Trackways and Footprints

Dinosaur trackways offer some of the most compelling evidence for social behavior among certain dinosaur species. Multiple parallel trackways of the same species heading in identical directions suggest coordinated movement similar to that seen in modern herds or packs. Particularly revealing are trackways showing different-sized footprints of the same species moving together, indicating family groups with adults and juveniles traveling as cohesive units. In locations such as the Davenport Ranch in Texas, hadrosaur trackways show dozens of individuals moving in the same direction, maintaining consistent spacing between individuals. These fossilized “snapshots” of dinosaur movement patterns provide direct evidence that at least some dinosaur species engaged in coordinated group behavior rather than living as solitary individuals.

Nesting Sites and Colonial Breeding

Discoveries of extensive nesting grounds have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur reproductive behavior and potential social structures. Sites like “Egg Mountain” in Montana reveal hundreds of Maiasaura nests nearby, suggesting colonial nesting similar to that seen in modern birds. The organization of these nesting colonies, with nests spaced at regular intervals, indicates a level of social coordination among breeding adults. Even more telling is evidence that some species, such as Maiasaura, remained at nest sites to care for their young after hatching, as indicated by the development stage of hatchling bones found in nests. This parental care represents a significant social investment and suggests more complex social relationships than previously assumed for reptilian animals. The communal nature of these nesting grounds points to social systems that may have included protection of young through group vigilance.

Pack Hunting Theories in Predatory Dinosaurs

The possibility of coordinated pack hunting among certain theropod dinosaurs represents one of the most wolf-like social behaviors hypothesized in the dinosaur world. Evidence supporting this theory includes sites where multiple predator species appear to have attacked a single large prey animal, such as the famous “Fighting Dinosaurs” specimen showing a Velociraptor locked in combat with a Protoceratops. More compelling are bonebeds containing multiple individuals of the same predator species, such as the Deinonychus assemblages associated with Tenontosaurus remains. These findings suggest multiple predators may have attacked a single, larger prey animal – a strategy that would require coordination similar to that seen in wolf packs. The anatomical adaptations of certain theropods, including enlarged brains and stereoscopic vision, further support the cognitive capacity necessary for coordinated hunting behaviors.

Social Hierarchies and Dominance Displays

Anatomical features of many dinosaur species suggest potential social hierarchies were maintained through visual displays rather than just physical combat. The elaborate crests, frills, and horns of dinosaurs like Parasaurolophus, Triceratops, and Pachycephalosaurus likely served communication functions within social groups. These structures show evidence of being display features rather than purely defensive adaptations, suggesting roles in establishing dominance hierarchies or attracting mates. Studies of bone microstructure in such ornamental features reveal high vascularization, indicating they may have been used for visual signaling through blood flow changes, similar to how modern birds use wattles and combs in social displays. The presence of these specialized social signaling adaptations suggests social structures complex enough to warrant elaborate communication systems within the species.

Age-Based Social Organization

Growth series fossils from single dinosaur species provide insights into potential age-based social structures reminiscent of wolf packs. Especially revealing are finds like the Coelophysis quarry at Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, where dozens of individuals of different ages were preserved together. Such assemblages suggest groups comprised of multiple age cohorts living together rather than age segregation. In some hadrosaur and ceratopsian species, studies of bone beds indicate that individuals of various growth stages died together, suggesting mixed-age social groups. This pattern differs from many reptiles but resembles mammalian social structures where experience from older individuals benefits group survival. The presence of juveniles, sub-adults, and adults in the same fossil assemblages suggests complex social relationships that possibly included knowledge transfer between generations.

Brain Size and Social Complexity

Endocasts of dinosaur braincases provide tantalizing clues about cognitive capabilities that would support complex social behavior. Certain dinosaur groups, particularly maniraptoran theropods like Troodon, possessed remarkably large brains relative to their body size compared to other reptiles. These enlarged brains featured expanded cerebral hemispheres, areas associated with higher cognitive functions in modern animals. Particularly significant is evidence of well-developed optic lobes, suggesting sophisticated visual processing critical for social species that rely on visual cues for communication. The encephalization quotient (brain-to-body ratio) of some theropods approaches that of modern birds, which frequently display complex social behaviors. These neurological adaptations would have provided the cognitive foundation necessary for maintaining the social memories and recognition capabilities essential to wolf-like pack structures.

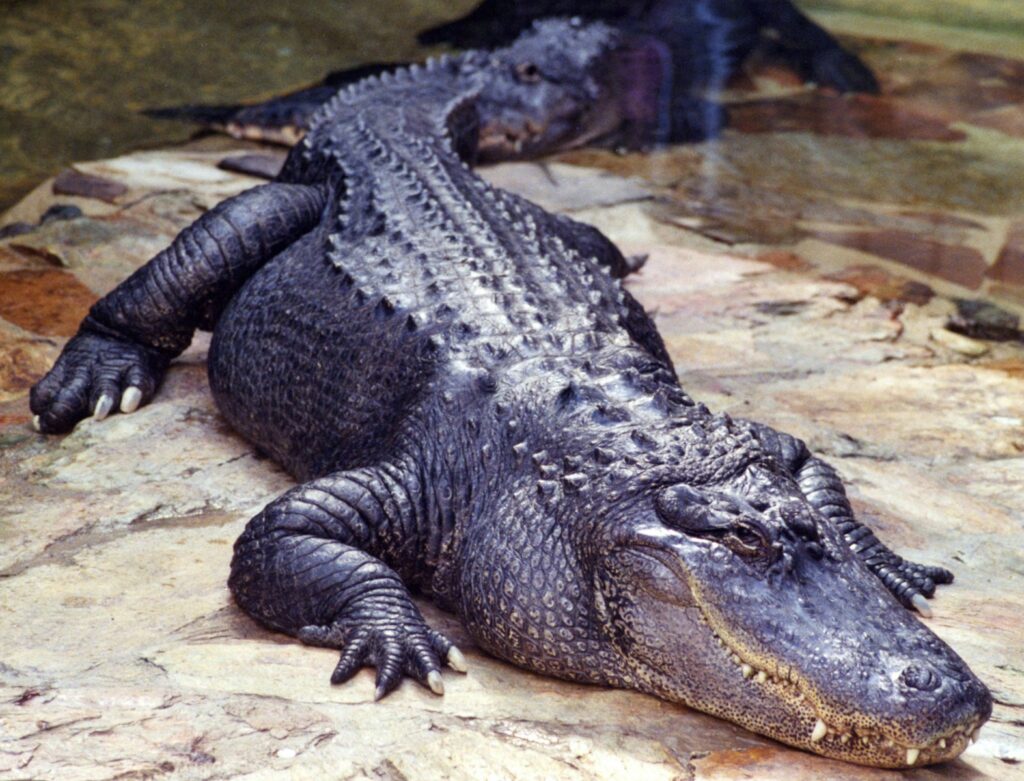

Comparing Evidence with Modern Social Animals

Drawing parallels between dinosaur evidence and modern animal behavior provides a framework for understanding potential dinosaur sociality. While wolves represent one model of complex social structure, scientists also compare dinosaur evidence with modern birds (dinosaurs’ closest living relatives) and crocodilians (another archosaur group). Many modern birds display elaborate social systems ranging from pair bonds to complex hierarchical flocks, suggesting similar potential in their dinosaur ancestors. The discovery that some dinosaurs, particularly theropods, possessed feathers further strengthens the behavioral connections to birds. Crocodilians, though less socially complex than wolves, still demonstrate coordinated hunting, communal nesting, and parental care – behaviors that may represent baseline social capacities present in the common ancestor of dinosaurs and crocodilians. These comparative approaches help scientists establish plausible boundaries for dinosaur social complexity.

Parental Care as Social Foundation

Evidence of extended parental care in dinosaurs suggests the fundamental social bonds that could evolve into more complex social structures. Fossil nests containing partially grown juveniles, particularly among hadrosaurs like Maiasaura (whose name means “good mother lizard”), indicate that parents provided extended care to offspring well beyond hatching. This contrasts with the minimal parental investment seen in many modern reptiles. Even more revealing are adult specimens found in direct association with multiple juveniles, suggesting protection or feeding of young similar to modern wolves’ care for pups. The wear patterns on teeth of adult hadrosaurs compared to juveniles suggest different feeding strategies, possibly indicating parents processed food for younger individuals. This level of parental investment represents a critical evolutionary foundation for more complex social bonds extending beyond immediate family groups.

Evolutionary Advantages of Dinosaur Sociality

Examining the selective pressures that would favor social structures helps evaluate which dinosaur groups most likely developed wolf-like social systems. For medium-sized predatory dinosaurs like dromaeosaurs, pack hunting would have provided access to prey significantly larger than individuals could handle alone, just as it does for wolves. For large herbivores like sauropods and ceratopsians, moving in herds would have reduced predation risk through increased vigilance and the dilution effect. Social living also creates opportunities for cooperative defense of the young, as seen in modern ungulate herds and bird colonies. The recurring evolution of sociality across multiple animal lineages suggests powerful adaptive advantages that would likely have applied to dinosaurs facing similar environmental challenges. These evolutionary benefits make it plausible that at least some dinosaur lineages independently evolved social structures comparable to those of modern wolves.

Communication Methods Among Social Dinosaurs

Effective communication forms the backbone of complex social structures in modern animals, raising questions about how dinosaurs might have coordinated group behaviors. Anatomical evidence suggests multiple communication channels were available to dinosaurs. The elaborate resonating chambers in hadrosaur crests would have produced distinctive sounds for long-distance communication within herds. Evidence of good vision in predatory dinosaurs indicates visual signals likely played a key role in their social interactions. The discovery of feathers in many theropod dinosaurs suggests the potential for visual displays similar to those used by modern birds for social signaling. Even scent marking, though difficult to detect in the fossil record, was likely important given the well-developed olfactory regions in many dinosaur endocasts. These multiple communication channels would have provided the necessary foundation for coordinating the complex social behaviors observed in modern pack animals.

Differing Social Structures Across Dinosaur Groups

The diversity of dinosaurs suggests varying degrees of social complexity across different lineages rather than a uniform pattern. Sauropods likely formed simple herds offering protection through numbers but perhaps lacking the complex social dynamics seen in wolves. Ceratopsians, with their elaborate cranial displays, may have maintained dominance hierarchies within relatively stable social groups. Evidence suggests that the most wolf-like social structures would have occurred among certain theropods, particularly dromaeosaurs and troodontids, with their enhanced sensory capabilities and cognitive potential. Hadrosaurs represent another group with compelling evidence for complex sociality, including migratory herds and extensive parental care. This diversity of social arrangements reflects the varied ecological niches dinosaurs occupied, with different selective pressures favoring different types of social organization. Just as modern mammals exhibit a spectrum of sociality from solitary to highly cooperative species, dinosaurs likely displayed a similar range of social adaptations.

Future Research and Unanswered Questions

Despite significant advances in understanding dinosaur sociality, critical questions remain that guide ongoing research. New technological approaches like CT scanning of fossils reveal previously inaccessible details about brain structure and sensory capabilities that would have influenced social behavior. Chemical analysis of fossil bone microstructure may eventually provide insights into stress hormones that could indicate social stress similar to that experienced by subordinate members in modern hierarchical groups. Continued discoveries of mass death assemblages and trackway sites will further clarify which species traveled in groups and their age compositions. Computer modeling of dinosaur biomechanics and predator-prey dynamics helps test hypotheses about the advantages of cooperative hunting or herding behaviors under different conditions. As research methodologies continue to advance, our understanding of dinosaur social structures will inevitably become more nuanced, potentially revealing social complexities rivaling those of modern wolves and other highly social vertebrates.

Conclusion

The question of whether dinosaurs maintained wolf-like social structures cannot be answered with absolute certainty, but the accumulating evidence suggests many dinosaur species were far more socially complex than traditionally portrayed. From coordinated movement patterns and colonial nesting to potential pack hunting and sophisticated communication systems, multiple lines of evidence point to social capabilities that in some cases may indeed have rivaled those of modern wolves. Different dinosaur lineages likely developed varying levels of sociality in response to their specific ecological pressures, just as we see in modern animals. While we may never have complete knowledge of dinosaur behavior, continuing research promises to further illuminate the social lives of these fascinating creatures, revealing increasingly sophisticated portraits of dinosaurs not just as biological entities but as social beings navigating their ancient worlds through cooperation and communication.