When we imagine dinosaurs, we typically picture them roaming across prehistoric landscapes, hunting or grazing in ancient forests and plains. However, paleontological evidence increasingly suggests that many dinosaur species were quite comfortable in aquatic environments. Recent fossil discoveries and anatomical studies have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur capabilities, revealing that some species weren’t just capable of swimming but were specialized for aquatic lifestyles. From Spinosaurus with its paddle-like tail to duck-billed hadrosaurs with webbed feet, the evidence points to a much more diverse range of dinosaur behaviors than previously thought. This article explores the fascinating evidence that some dinosaurs weren’t just occasional swimmers but might have been exceptional divers and aquatic predators.

The Prehistoric Swimming Debate

The question of whether dinosaurs could swim has been debated among paleontologists for decades. Early assumptions that dinosaurs were strictly terrestrial animals have gradually given way to a more nuanced understanding. The swimming capabilities of dinosaurs haven’t been easy to determine from the fossil record alone, as swimming behaviors don’t always leave obvious skeletal markers. However, various lines of evidence, including fossil trackways showing possible swim marks, anatomical adaptations, and depositional environments where fossils are found, have all contributed to our current understanding. Today, most paleontologists agree that many dinosaurs could probably swim when necessary, similar to many modern land animals, but the debate centers more on which species might have been specialized for aquatic lifestyles rather than whether dinosaurs could swim at all.

Spinosaurus: The Dinosaur Swimmer That Rewrote History

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus represents perhaps the most dramatic evidence for swimming dinosaurs. This massive theropod, larger even than the Tyrannosaurus rex, lived approximately 99-93.5 million years ago in what is now North Africa. The discovery of a remarkably complete Spinosaurus tail in Morocco in 2020 revolutionized our understanding of this dinosaur. The tail was notably different from other theropods, featuring tall neural spines that created a fin-like structure perfect for propulsion through water. Biomechanical studies of this tail confirmed it would have been an efficient swimming appendage, similar to those of modern crocodilians but even more specialized. This evidence, combined with its crocodile-like snout and dense bones that would have helped with buoyancy control, strongly suggests Spinosaurus was primarily aquatic, potentially the first known swimming dinosaur specialized for hunting in deep water environments.

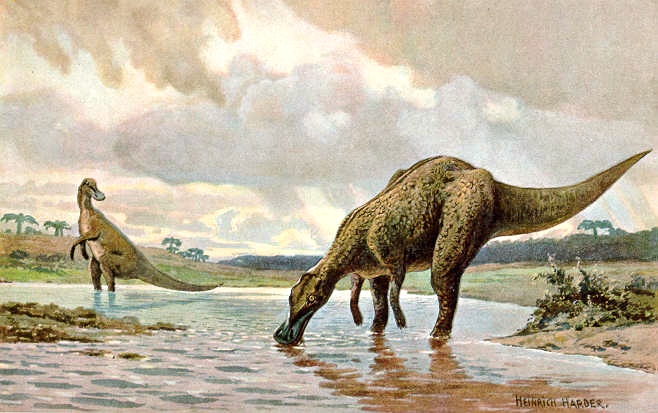

Duck-Billed Dinosaurs: Built for Both Land and Water

Hadrosaurs, commonly known as duck-billed dinosaurs, show several adaptations suggesting they were comfortable in aquatic environments. These herbivorous dinosaurs possessed powerful tails that could have provided propulsion in water, similar to modern crocodilians. Some fossil specimens show evidence of webbing between their fingers, which would have aided in swimming. Their namesake duck-like bills were likely used for filter-feeding aquatic vegetation, much like modern ducks. Particularly compelling evidence comes from trackways discovered in Spain, Alaska, and other locations showing hadrosaur footprints transitioning from walking to swimming patterns as the dinosaurs entered deeper water. The combination of these anatomical features and behavioral evidence strongly suggests that hadrosaurs were semi-aquatic dinosaurs, capable of efficient locomotion both on land and in water environments.

Dinosaur Trackways: Footprints in Ancient Shorelines

Fossil trackways have provided some of the most direct evidence of swimming dinosaurs. In several locations worldwide, paleontologists have discovered dinosaur tracks that transition from clear footprints to marks where only claw tips touched the bottom, indicating the animal was swimming with its body buoyant in the water. These “swim tracks” provide a remarkable snapshot of behavior, showing dinosaurs actively swimming rather than just wading. Particularly notable are trackways found in Spain and Korea showing evidence of dinosaurs using their powerful hind limbs to push against the bottom while their bodies floated. Some tracks even show tail drag marks that suggest how the dinosaurs were using their tails for stabilization or propulsion while swimming. These fossil trackways offer rare glimpses of behavior that bone fossils alone cannot provide, giving us windows into the actual movements of dinosaurs in aquatic environments.

Baryonyx and Suchomimus: Fishing Specialists

Spinosaurids like Baryonyx and Suchomimus show compelling evidence for semi-aquatic lifestyles focused on fishing. Baryonyx, discovered in England, possessed a crocodile-like skull with conical teeth perfect for grasping slippery prey like fish. The smoking gun for its fishing lifestyle came with the discovery of fish scales and bones in the stomach region of a Baryonyx fossil. Suchomimus, meaning “crocodile mimic,” had similar adaptations, including large, curved claws that may have been used for gaffing fish from the water. Both dinosaurs had long, low snouts with nostrils positioned high on the skull, an adaptation seen in modern crocodilians that allows breathing while partially submerged. Their center of gravity and posture also suggest comfort near water, with dense bones that would have provided ballast for swimming and diving. These adaptations point to spinosaurids as specialized fish-eaters that were likely excellent swimmers.

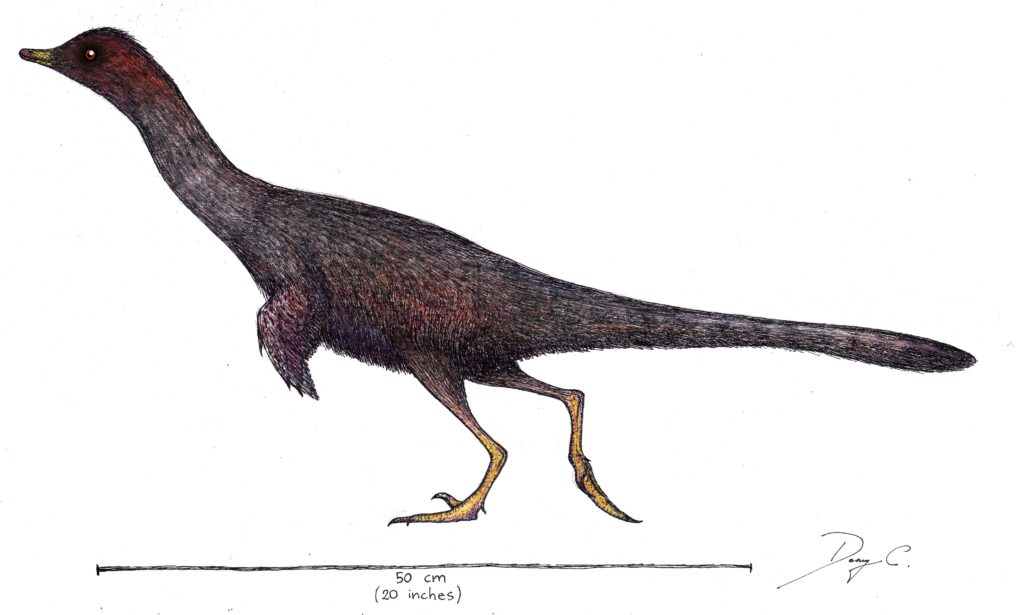

The Halszkaraptor Mystery: A Swimming Raptor?

One of the most unexpected swimming dinosaurs may have been Halszkaraptor escuilliei, a small dromaeosaurid (raptor) dinosaur that lived in Mongolia about 75 million years ago. This unusual dinosaur shows a combination of features never before seen in dinosaurs but reminiscent of modern aquatic birds. Its forelimbs appear to have been modified for swimming like penguins, while its long neck and snout, filled with sensitive teet, suggest it hunted for small prey in shallow waters. CT scans of the fossil revealed a network of neurovascular canals in its snout similar to those in modern aquatic birds that use touch to locate prey underwater. Additionally, its bone density patterns match those of diving birds rather than land-dwelling dinosaurs. While some paleontologists remain cautious about these interpretations, Halszkaraptor remains one of the most intriguing potential examples of a highly specialized swimming dinosaur from an unexpected family.

Diving Capabilities: Could Dinosaurs Submerge?

Beyond simple swimming, evidence suggests some dinosaurs may have been capable of active diving and underwater foraging. Bone density studies provide compelling evidence for this behavior. Several dinosaur species, particularly spinosaurids, show a condition called pachyostosis – unusually dense, heavy bones that would have provided ballast, making diving easier. This condition is commonly seen in modern diving animals like penguins and hippos. Some dinosaurs also show evidence of enlarged nasal cavities that may have housed specialized tissues to help manage pressure changes during diving. The structure of certain dinosaur lungs, inferred from their vertebral columns, suggests they may have had respiratory adaptations that would have facilitated underwater activity. While not as specialized as modern diving birds or marine mammals, these adaptations suggest that some dinosaurs could have actively pursued prey beneath the water’s surface for extended periods, particularly in freshwater environments.

Amphibious Dinosaurs: Living Between Two Worlds

Some dinosaur species appear to have lived truly amphibious lifestyles, comfortable both on land and in water. Beyond the already mentioned Spinosaurus, other candidates for amphibious lifestyles include certain ornithopods and theropods. The unusual theropod Limusaurus, for instance, shows evidence of having frequented boggy environments. Some hadrosaurs appear to have been well-adapted for navigating swampy terrain, with wide, possibly webbed feet that would have prevented sinking in mud and facilitated swimming. Fossil evidence of stomach contents and coprolites (fossilized feces) sometimes reveal mixtures of terrestrial and aquatic plant material, suggesting these dinosaurs foraged in both environments. Studies of bone microstructure in some of these species show patterns consistent with animals that spend significant time in water, similar to modern amphibious mammals like hippopotamuses. These dinosaurs likely exploited the resources of both aquatic and terrestrial environments, moving between them as needed for feeding, protection, or thermoregulation.

Swimming Mechanics: How Dinosaurs Moved Through Water

Biomechanical studies have provided insights into how different dinosaurs likely propelled themselves through water. Theropods like Spinosaurus appear to have used undulating, crocodile-like tail movements, with their tall neural spines creating an effective paddle shape that would have generated significant thrust. Computer modeling of these movements suggests they were remarkably efficient swimmers. Hadrosaurs and other ornithopods likely used their powerful hind limbs for propulsion, similar to modern frogs but on a much larger scale. Their muscular tails would have provided additional propulsion and steering capability. Some smaller theropods, particularly those with evidence of swimming adaptations like Halszkaraptor, may have used their forelimbs as paddles like modern aquatic birds. Muscle attachment points visible on fossils allow paleontologists to reconstruct the musculature that would have powered these different swimming styles, revealing diverse approaches to aquatic locomotion among dinosaur lineages.

Marine Reptiles vs. Swimming Dinosaurs

It’s important to distinguish between true swimming dinosaurs and the fully marine reptiles that lived alongside them. Iconic marine creatures like plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and mosasaurs were reptiles but not dinosaurs; they belonged to different evolutionary lineages that returned to the sea much like whales did millions of years later. These marine reptiles evolved flippers and fully aquatic lifestyles, becoming unable to move effectively on land. In contrast, even the most aquatic dinosaurs like Spinosaurus retained functional limbs for land movement, suggesting they remained semi-aquatic rather than fully committed to marine life. This fundamental difference highlights an evolutionary puzzle: Despite their 165 million years of dominance and remarkable diversity, dinosaurs never evolved fully marine forms like whales or seals, instead remaining primarily terrestrial and freshwater-adapted animals. This pattern may reflect ecological competition with the already well-established marine reptiles of the Mesozoic Era.

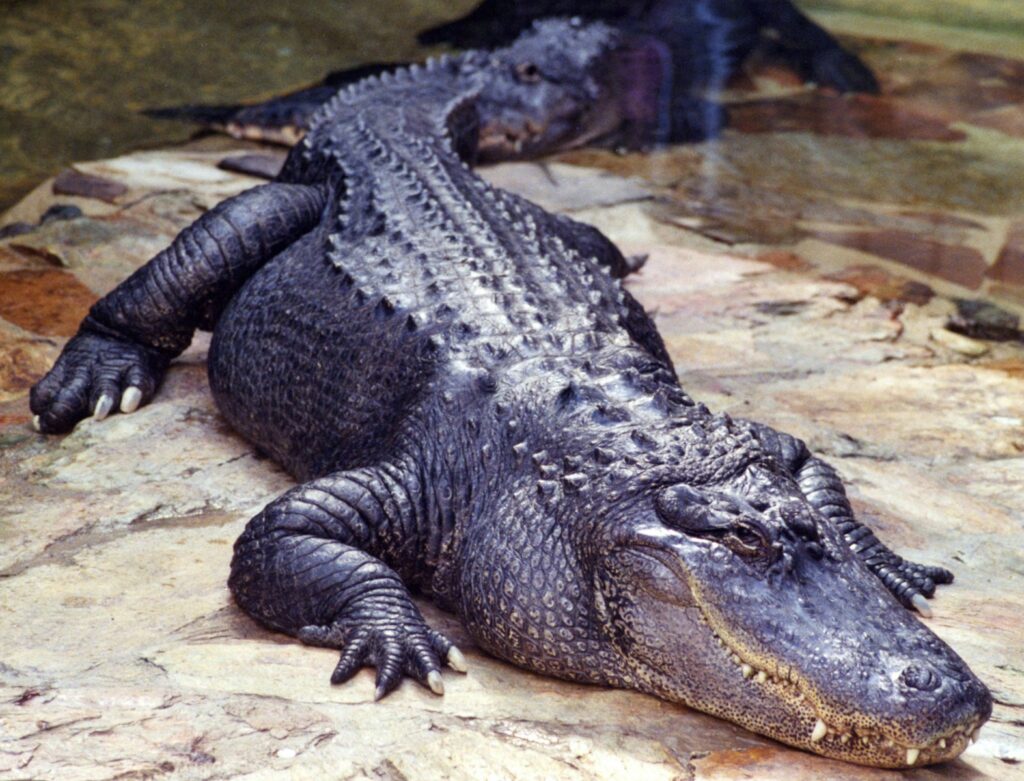

Modern Analogues: Birds and Crocodilians

Studying the aquatic capabilities of dinosaurs’ modern relatives provides valuable insights into potential dinosaur swimming behaviors. Birds, which are technically living dinosaurs, show a wide range of aquatic adaptations from the casual swimming of ducks to the specialized diving of penguins and cormorants. These adaptations demonstrate the evolutionary flexibility of the dinosaur body plan when it comes to water adaptation. Crocodilians, the closest living relatives to dinosaurs outside of birds, are highly capable swimmers that use powerful tail strokes for propulsion. The swimming mechanisms of crocodiles likely resemble those of some swimming dinosaurs, particularly theropods with similar body plans. By studying the bone densities, muscle attachments, and biomechanics of modern swimming birds and crocodilians, paleontologists can create more accurate reconstructions of how extinct dinosaurs might have moved through water. These living analogues provide critical reference points for understanding the swimming capabilities that existed within the dinosaur family tree.

Ecosystem Implications: Aquatic Dinosaur Niches

The recognition that many dinosaurs were adept swimmers has significant implications for our understanding of Mesozoic ecosystems. Swimming dinosaurs would have occupied ecological niches previously thought to be dominated exclusively by crocodilians and marine reptiles. As top predators in freshwater environments, semi-aquatic dinosaurs like Spinosaurus would have influenced the entire food web, potentially competing with large crocodilians for resources. Herbivorous swimming dinosaurs like hadrosaurs would have impacted aquatic vegetation and transported nutrients between terrestrial and aquatic systems. The presence of swimming dinosaurs also suggests more complex wetland ecosystems than previously envisioned, with dinosaurs potentially migrating between water bodies along river systems. Fossil evidence of multiple swimming dinosaur species in the same formations indicates they likely partitioned aquatic resources through specialization, much as modern waterbirds occupy different niches within the same wetland. These insights help paleontologists reconstruct more complete and accurate pictures of ancient ecosystems.

Ongoing Discoveries: The Future of Aquatic Dinosaur Research

Research into swimming dinosaurs continues to accelerate with new methodologies and fossil discoveries. Advanced techniques such as bone histology, which examines microscopic bone structure, can reveal patterns indicative of aquatic lifestyles through bone density and growth patterns. Isotopic analysis of dinosaur teeth provides information about diet and habitat, potentially distinguishing between terrestrial and aquatic feeding patterns. CT scanning of fossils reveals internal structures that might indicate swimming adaptations not visible from external examination. Computer modeling and simulation continue to improve our understanding of dinosaur biomechanics, including swimming capabilities. Paleontologists are also increasingly examining the depositional environments where dinosaur fossils are found, providing contextual clues about their habitats. As new fossils are discovered in previously unexplored regions, particularly in river and lake deposits, our picture of swimming dinosaurs will likely become even more diverse and nuanced in coming years, potentially revealing even more specialized aquatic dinosaurs waiting to be discovered.

Dinosaurs in Water: Evidence of Swimming and Diving

The evidence for swimming and diving dinosaurs has grown substantially in recent decades, challenging our traditional view of dinosaurs as exclusively terrestrial animals. From the fish-hunting Spinosaurus with its paddle-like tail to duck-billed hadrosaurs leaving swimming trackways in ancient mud, it’s clear that many dinosaurs were perfectly at home in water. Some species show adaptations specifically for aquatic lifestyles, including dense bones for diving, specialized limb structures for swimming, and feeding adaptations for aquatic prey. As paleontological methods continue to advance, we’re likely to discover even more examples of dinosaurs that weren’t just occasional swimmers but specialized aquatic predators. This expanding understanding reminds us that dinosaurs were remarkably adaptable creatures that successfully exploited virtually every habitat available to them during their long reign, including the underwater world.