When dinosaurs roamed the Earth, another group of reptiles was quietly establishing its evolutionary legacy. Crocodilians—the group that includes modern crocodiles and alligators—not only lived alongside dinosaurs but managed to survive the catastrophic extinction event that wiped out their larger reptilian cousins 66 million years ago. Today’s crocodiles represent one of evolution’s most remarkable success stories, maintaining a body plan that has remained largely unchanged for over 200 million years while adapting to shifting environments and climates. Their survival through multiple mass extinctions offers fascinating insights into evolutionary resilience and adaptation. This article explores the extraordinary evolutionary journey of crocodilians, from their ancient origins to their position as the closest living relatives of the extinct dinosaurs and the birds that evolved from them.

Ancient Origins: The Archosaur Connection

Crocodilians belong to a larger group called archosaurs, the “ruling reptiles” that also gave rise to dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and eventually birds. This relationship explains many of the similarities between crocodiles and birds, despite their vastly different appearances. The archosaur lineage split approximately 250 million years ago during the early Triassic period, with one branch leading to dinosaurs and eventually birds, while the other led to crocodilians. This common ancestry makes crocodiles more closely related to birds than to other living reptiles like snakes, lizards, or turtles. Their shared archosaur heritage is evident in various anatomical features, including their four-chambered hearts, similar ankle structures, and advanced respiratory systems that differ significantly from those of other reptiles. This evolutionary connection also explains why crocodilian behavior, especially parental care, bears more resemblance to birds than to other reptiles.

The First True Crocodilians

The earliest direct ancestors of modern crocodiles emerged during the Late Triassic period, around 230 million years ago. These animals, known as “sphenosuchians,” were quite different from the crocodiles we recognize today—they were smaller, more lightly built, and primarily terrestrial. Rather than being the slow, semi-aquatic ambush predators of modern times, many early crocodylomorphs were active, quick-moving land animals that likely chased down prey. Some species were even fully bipedal, running on their hind legs much like some dinosaurs. The transition to the semi-aquatic lifestyle came gradually, with many intermediate forms showing partial adaptations for water living. By the Jurassic period, around 200 million years ago, crocodylomorphs had diversified into a wide range of ecological niches, including fully marine species with paddle-like limbs, terrestrial hunters, and the semi-aquatic forms that would eventually give rise to modern crocodilians.

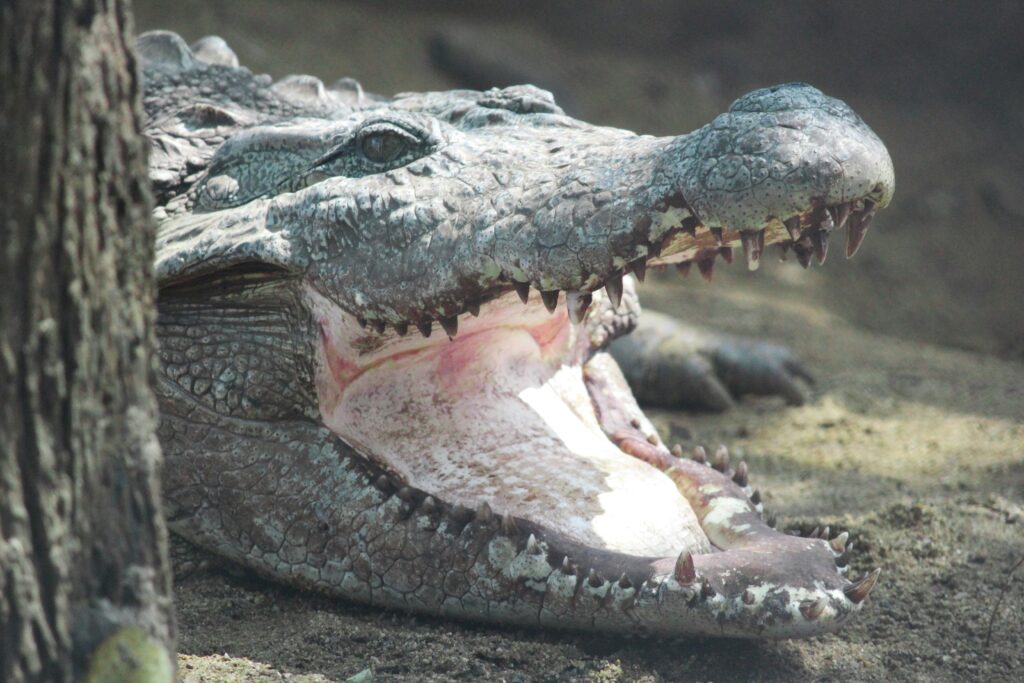

Anatomical Adaptations for Survival

Modern crocodilians possess a suite of specialized adaptations that have contributed to their evolutionary success. Their iconic armored bodies feature osteoderms—bony plates embedded in the skin that protect while still allowing flexibility. The crocodilian skull has undergone remarkable specialization, with elongated jaws lined with powerful conical teeth perfectly suited for capturing and holding prey. Their eyes, ears, and nostrils are positioned on top of the head, allowing them to remain nearly completely submerged while still able to see, hear, and breathe—a crucial adaptation for their ambush hunting strategy. Crocodilians also possess specialized valves at the back of their throats that seal off their respiratory systems when underwater, allowing them to open their mouths and capture prey without drowning. Perhaps most remarkable is their circulatory system, featuring a four-chambered heart that can selectively bypass the lungs during diving, effectively functioning like both a reptilian and mammalian heart depending on circumstances.

From Land to Water: The Aquatic Transition

The evolutionary shift from primarily terrestrial to semi-aquatic lifestyles represents one of the most significant transformations in crocodilian evolution. This transition involved profound changes to their anatomy, physiology, and behavior. Their limbs became shorter and more paddle-like, though still capable of powerful terrestrial movement. Their tails evolved into muscular, laterally compressed swimming organs that propel them through water with remarkable speed and agility. Their sensory systems adapted to aquatic environments, developing pressure receptors along their jaws that can detect minute water movements from potential prey, even in complete darkness. Physiologically, they developed enhanced abilities to regulate body temperature using their aquatic environment, improved oxygen storage capacity in their blood, and specialized metabolic adaptations that allow them to remain submerged for extended periods. This transition also coincided with changes in feeding strategy, as many lineages shifted from active pursuit predation to the ambush hunting style characteristic of modern crocodilians.

Marine Crocodilians: Masters of Ancient Oceans

While today’s crocodilians are primarily freshwater and estuarine species, their evolutionary history includes numerous lineages that conquered the open oceans. Thalattosuchia, commonly called “sea crocodiles,” were a group of highly specialized marine crocodylomorphs that evolved during the Jurassic period. These remarkable animals developed paddle-like limbs similar to those of sea turtles, fish-like tail fins, and streamlined bodies that made them formidable ocean predators. Some species, like Dakosaurus, evolved to become hypercarnivorous apex predators with serrated teeth resembling those of killer whales. Another group, the Metriorhynchidae, went even further in their marine adaptations, losing their osteoderms entirely to enhance swimming efficiency and developing salt glands to excrete excess salt from their marine environments. Unlike modern crocodilians that must return to land to lay eggs, some evidence suggests that the most advanced marine crocodylomorphs may have evolved live birth, similar to modern marine mammals and some other marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs.

Surviving the K-Pg Extinction Event

The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event 66 million years ago wiped out approximately 75% of all species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. Remarkably, crocodilians survived this catastrophic period relatively unscathed. Their survival has been attributed to several key factors that gave them an edge during this global cataclysm. Their semi-aquatic lifestyle may have provided some buffer against the immediate effects of the asteroid impact and subsequent environmental changes. Their ability to remain dormant for extended periods when conditions are unfavorable allowed them to weather food shortages. Additionally, crocodilians are opportunistic feeders capable of surviving on practically any available animal protein, including carrion, giving them flexibility when specific prey species disappear. Perhaps most importantly, their low metabolic rate meant they required far less food than similarly-sized warm-blooded animals, allowing them to survive on minimal resources during the post-impact environmental collapse. These combined adaptations effectively made crocodilians “survival specialists” pre-adapted to withstand the very conditions that proved fatal to dinosaurs.

Giant Crocodilians of the Past

Throughout their evolutionary history, crocodilians have included some truly massive species that dwarf even the largest modern examples. Perhaps the most famous prehistoric giant was Deinosuchus, which lived in North America during the Late Cretaceous period around 80 million years ago. Growing to estimated lengths of 10-12 meters (33-39 feet) and weighing up to 8-10 tons, Deinosuchus was large enough to prey upon dinosaurs, as evidenced by bite marks found on dinosaur fossils. Even more impressive was Sarcosuchus imperator, aptly nicknamed “SuperCroc,” which inhabited Africa during the Early Cretaceous. With estimated lengths reaching 11-12 meters (36-39 feet) and a weight of approximately 8 tons, it was one of the largest crocodylomorphs ever to exist. The Miocene epoch (23-5 million years ago) saw the evolution of Purussaurus, a caiman relative from South America that reached similar enormous dimensions. These giants evolved independently in different crocodilian lineages, demonstrating the group’s repeated tendency to produce apex predators when ecological conditions permitted.

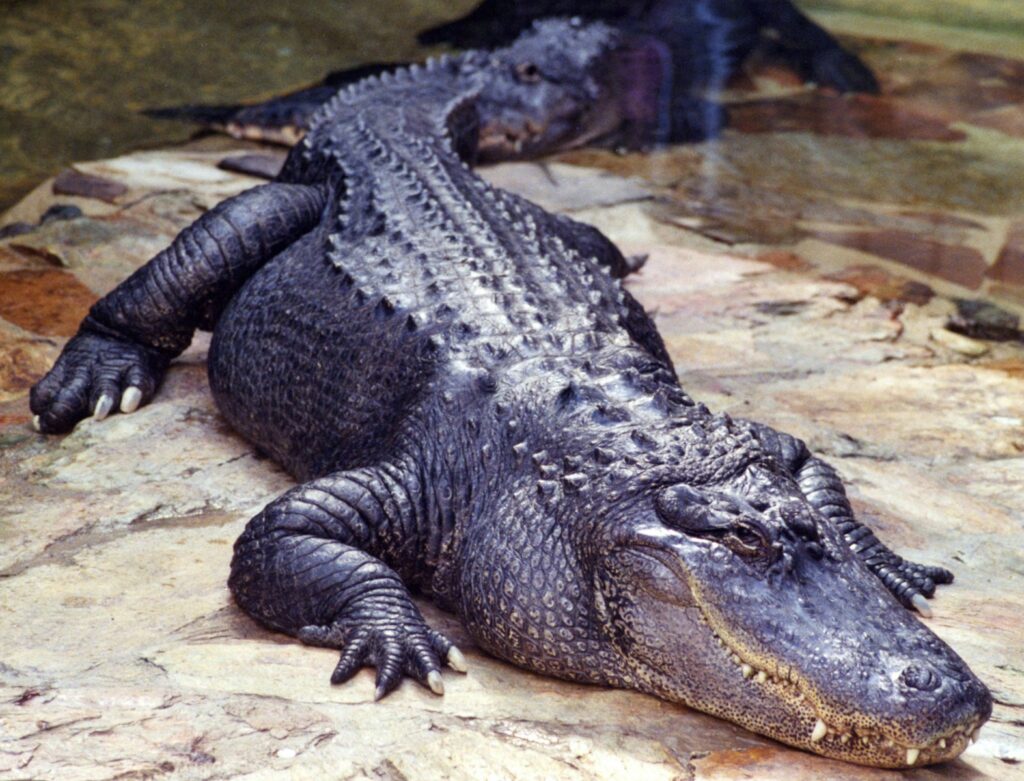

Modern Crocodilian Diversity

Today’s crocodilians represent just a fraction of their historical diversity, with 27 recognized species divided among three families: Crocodylidae (true crocodiles), Alligatoridae (alligators and caimans), and Gavialidae (gharials). Each family exhibits specialized adaptations for different ecological niches. True crocodiles generally have more V-shaped snouts and can tolerate saltwater due to specialized salt-excreting glands, allowing many species to inhabit coastal areas and even cross the open ocean. Alligators and caimans possess broader, U-shaped snouts better suited for crushing prey, and are primarily freshwater specialists lacking functional salt glands. Gharials represent the most specialized modern crocodilians, with extremely narrow snouts lined with needle-like teeth perfectly adapted for catching fish. The geographic distribution of these families reflects their evolutionary history: alligators are found in the Americas and China, true crocodiles have a pantropical distribution across Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas, while gharials are restricted to the Indian subcontinent. This modern diversity, though reduced from historical levels, still demonstrates the remarkable adaptability of this ancient lineage.

Evolutionary Stasis: Living Fossils?

Crocodilians are often described as “living fossils” due to their unchanged appearance over millions of years, but this characterization is somewhat misleading. While their basic body plan has remained recognizable for over 200 million years, crocodilians have undergone substantial evolutionary refinement during this time. Modern molecular studies reveal that crocodilians continue to evolve at the genetic level at rates comparable to other vertebrates, despite their morphological conservatism. Their seemingly unchanging appearance represents what evolutionary biologists call “stabilizing selection,” where the basic body plan is so well-adapted to its ecological niche that deviations are typically selected against. This doesn’t mean evolution has stopped—rather, it indicates that the crocodilian body plan represents a highly optimized solution for their semi-aquatic predatory lifestyle. The persistence of this body plan through vastly different global environments and climate regimes is testament not to evolutionary stagnation but to the remarkable effectiveness of the crocodilian design.

Molecular Evolution and Surprising Adaptations

Modern genomic research has revealed surprising aspects of crocodilian evolution invisible at the morphological level. Crocodilian genomes evolve more slowly than those of birds or mammals, providing valuable insight into ancestral archosaur genetics. Their immune systems have evolved remarkable antimicrobial properties, with blood that contains powerful antibiotics effective against a wide range of pathogens, including drug-resistant bacteria—adaptations likely developed from living in microbe-rich environments and dealing with serious injuries. Crocodilians also possess extraordinary healing abilities, recovering from severe wounds that would be fatal to most vertebrates. Genome sequencing has revealed unexpected sensory adaptations, including specialized neural structures for extreme sensitivity to touch around their faces and unique modifications to genes involved in light reception, suggesting more sophisticated vision than previously believed. Perhaps most surprisingly, research indicates that crocodilians possess highly developed parental care behaviors governed by complex neural circuitry more similar to birds than to other reptiles, reflecting their shared archosaur heritage and suggesting that such behaviors may have also been present in dinosaurs.

Climate Change and Past Crocodilian Distribution

The geographic distribution of crocodilians has expanded and contracted dramatically throughout geological history, largely in response to global climate fluctuations. During the Eocene thermal maximum, approximately 50 million years ago, when global temperatures were significantly warmer than today, crocodilians thrived in high-latitude regions that are currently temperate or even polar. Fossil evidence shows that crocodilians once inhabited the Arctic Circle on Ellesmere Island in what is now northern Canada, as well as Antarctica, when these regions supported lush forests in Earth’s warmer past. As global cooling occurred and ice ages became more frequent during the past few million years, crocodilian ranges contracted toward the equator, restricting them to the tropical and subtropical regions they inhabit today. This climate-driven distribution pattern makes crocodilians excellent proxies for paleoclimate research, as their presence in the fossil record typically indicates warm, wet conditions. The historical presence of crocodilians in polar regions also demonstrates that these animals are not intrinsically restricted to tropical environments but rather limited by modern climate conditions.

Future Challenges to Crocodilian Survival

Despite surviving multiple mass extinctions and 200 million years of environmental changes, many crocodilian species now face unprecedented threats primarily from human activities. Habitat destruction poses perhaps the most significant challenge, as wetlands and waterways are drained, dammed, or polluted for agriculture and development. Hunting for skins and meat reduced many populations to critical levels during the 20th century, though international protection and sustainable use programs have allowed some recovery. Climate change presents complex challenges, potentially expanding suitable habitat in some regions while eliminating it in others through changing rainfall patterns and extreme weather events. Rising sea levels threaten coastal nesting areas for many species, while changing temperatures may affect sex determination in eggs, as crocodilian gender is determined by incubation temperature. Invasive species and diseases represent additional emerging threats to some populations. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection, sustainable management programs that provide economic incentives for local communities, and captive breeding initiatives for critically endangered species like the Chinese alligator and Philippine crocodile.

Crocodilian Cognition and Behavior

Research increasingly reveals that crocodilians possess cognitive abilities far more sophisticated than traditionally recognized, challenging long-held perceptions of reptiles as primitive or unintelligent. Crocodilians demonstrate complex social behaviors, with intricate dominance hierarchies and social recognition capabilities that allow them to remember and respond differently to familiar and unfamiliar individuals. They engage in sophisticated hunting strategies, including cooperative hunting techniques where multiple individuals work together to herd fish or position themselves to trap prey. Tool use has been documented in multiple species, with crocodilians using sticks as bait to attract nesting birds, positioning the sticks on their snouts during nesting seasons when birds are searching for building materials. Their parental care is remarkably developed, with mothers responding to specific vocalizations from hatchlings and defending them fiercely for extended periods. Crocodilians also display impressive learning abilities, quickly adapting to new situations and remembering solutions to problems over long periods. These cognitive capabilities likely contributed significantly to their evolutionary success and ability to adapt to changing environments over millions of years.

Evolutionary Lessons from Crocodilian Survival

The extraordinary evolutionary journey of crocodilians offers valuable insights into biological resilience and adaptation that extend beyond these remarkable reptiles. Their survival through multiple mass extinctions demonstrates the value of evolutionary versatility—crocodilians possess adaptations that allow them to withstand extended periods of resource scarcity, including the ability to drastically lower their metabolic rates and survive without food for months or even years if necessary. Their success highlights the effectiveness of a generalist strategy in uncertain environments, as crocodilians can utilize virtually any prey they can catch and occupy habitats ranging from freshwater to marine environments. The persistence of crocodilians also illustrates that evolutionary success isn’t always about rapid change or innovation but can involve refining and maintaining an effective body plan across changing conditions. Perhaps most importantly, crocodilian survival reminds us that evolution does not follow a ladder of “progress” toward more complex forms—these ancient reptiles have persisted not because they were primitive but because they were supremely well-adapted to their ecological niches. In a changing world facing increasing extinction pressures, the lessons of crocodilian resilience may prove more relevant than ever.

The Evolutionary Resilience of Earth’s Oldest Reptilian Predators

Crocodilians represent one of evolution’s most remarkable success stories, maintaining their distinctive form and ecological role for over 200 million years through periods of dramatic environmental change that eliminated countless other lineages, including the non-avian dinosaurs. From their origins as terrestrial archosaurs to their adaptation to aquatic environments, their survival through the K-Pg extinction event, and their continued persistence in modern ecosystems, crocodilians demonstrate extraordinary evolutionary resilience. Today, as we face unprecedented rates of species loss and environmental change, these ancient survivors offer valuable lessons about adaptation and survival. The continued success of crocodilians in the modern world will depend largely on human conservation efforts, determining whether these remarkable reptiles that outlived the dinosaurs will continue their extraordinary evolutionary journey into the future.