In the popular imagination, dinosaurs often conjure images of towering terrestrial giants roaming prehistoric landscapes. Their dominance on land has been well-documented through fossil discoveries and scientific research. However, a question that frequently emerges is whether these remarkable reptiles ever ventured into the vast oceanic realms that cover much of our planet. The answer reveals a fascinating chapter in Earth’s prehistoric story, challenging some common assumptions about dinosaur habitats and lifestyles. Let’s dive into the surprising truth about dinosaurs and their relationship with marine environments.

Defining What Makes a Dinosaur

To accurately answer whether dinosaurs lived in oceans, we must first establish what scientifically constitutes a dinosaur. Dinosaurs belong to a specific group of reptiles that emerged during the Triassic period about 245 million years ago. They are defined by distinct anatomical features, including their upright stance with legs positioned directly beneath their bodies, rather than sprawling to the sides like many other reptiles. This classification is crucial because many prehistoric marine reptiles are often mistakenly labeled as dinosaurs in popular culture. Scientifically speaking, dinosaurs form a natural group (clade) descended from a common ancestor, with specific skeletal characteristics that unite them and distinguish them from other reptilian groups.

The True Habitat of Dinosaurs

Dinosaurs, by scientific definition, were exclusively terrestrial animals. They evolved specific adaptations for life on land, including limb structures designed for supporting weight against gravity and respiratory systems optimized for air breathing. Throughout their 165-million-year reign on Earth, from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous period, dinosaurs diversified enormously, occupying virtually every terrestrial habitat from dense forests to arid deserts and from coastal plains to mountainous regions. Some species ventured into freshwater environments occasionally, but none evolved the specialized adaptations necessary for a fully aquatic lifestyle in oceans. Their skeletal structure and physiological features remained fundamentally suited for land-dwelling existence, even as they diversified into thousands of species across the planet.

Common Misconceptions About Marine Dinosaurs

Many prehistoric marine reptiles are frequently misidentified as dinosaurs in popular media and culture. Creatures like plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and mosasaurs often appear in dinosaur books and toys, creating widespread confusion about dinosaur classification. This misconception is so pervasive that many people are genuinely surprised to learn that iconic marine reptiles like the long-necked Elasmosaurus or dolphin-shaped Ichthyosaurus were not dinosaurs at all. The confusion stems partly from the fact that these creatures lived during the “Age of Dinosaurs” and, like dinosaurs, were reptiles. However, they belonged to entirely different evolutionary lineages that diverged from the dinosaur line millions of years earlier. These marine reptiles evolved from land-dwelling ancestors who returned to the sea, similar to how whales evolved from land mammals.

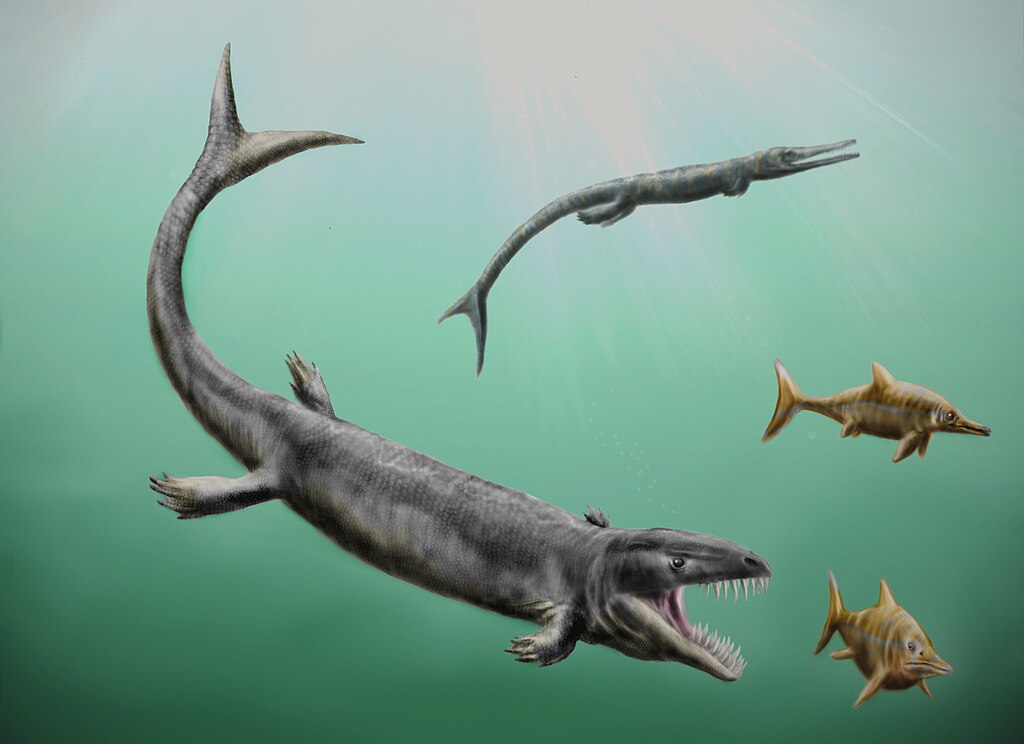

The Great Marine Reptiles of the Mesozoic

While dinosaurs ruled the land, the oceans teemed with remarkable reptilian predators that dominated marine ecosystems. Ichthyosaurs, with their streamlined, dolphin-like bodies and powerful tails, became sophisticated oceanic hunters during the Triassic and reached their peak in the Jurassic period. Plesiosaurs, characterized by their long necks, small heads, and paddle-like limbs, emerged in the Late Triassic and diversified throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Perhaps most formidable were the mosasaurs, giant marine lizards related to modern monitor lizards and snakes, which rose to prominence in the Late Cretaceous, with some species growing to lengths exceeding 50 feet. These marine reptiles evolved spectacular adaptations for aquatic life, including streamlined bodies, fins or flippers modified from limbs, and specialized breathing mechanisms. Despite living alongside dinosaurs temporally, they represent separate evolutionary lines that mastered life in the ocean while dinosaurs dominated on land.

The Evolutionary Relationships

Understanding the evolutionary relationships between dinosaurs and marine reptiles clarifies why we don’t find true dinosaurs in ancient oceans. Dinosaurs belong to the archosaur lineage, which also includes crocodilians and birds. Marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs evolved from different reptilian ancestors. Mosasaurs, for instance, were derived from terrestrial lizards related to modern Komodo dragons and developed adaptations for marine life independently. The distinction is similar to how whales and dolphins are mammals, not fish, despite their aquatic lifestyle. This evolutionary divergence occurred deep in the reptilian family tree, well before dinosaurs emerged as a distinct group. While dinosaurs were developing specialized features for terrestrial dominance, these other reptilian lineages were undergoing their own remarkable evolutionary journey into marine environments, resulting in parallel but separate success stories in Earth’s Mesozoic ecosystems.

Spinosaurus: The Swimming Dinosaur?

Recent discoveries about Spinosaurus aegyptiacus have dramatically challenged our understanding of dinosaur lifestyles. This massive theropod dinosaur from North Africa, known for its impressive sail-like structure on its back, has emerged as the strongest candidate for a semi-aquatic dinosaur. Fossil evidence reveals adaptations unprecedented among dinosaurs: dense bones for buoyancy control, a crocodile-like snout with sensory pits for detecting underwater prey, and most remarkably, a paddle-like tail that could have propelled it through water with considerable efficiency. Paleontologists now believe Spinosaurus spent significant time hunting in rivers and lakes, perhaps even pursuing prey underwater. However, it’s crucial to note that even Spinosaurus wasn’t a fully marine creature like whales or mosasaurs – it likely hunted in freshwater environments rather than open oceans. Its adaptations represent the closest any known dinosaur came to an aquatic lifestyle, occupying a unique ecological niche between land and water.

Other Water-Friendly Dinosaurs

While Spinosaurus stands out for its aquatic adaptations, several other dinosaur species showed features suggesting comfort around water environments. Baryonyx, another spinosaurid with crocodile-like jaws and fish remains preserved in its stomach cavity, likely specialized in catching fish along riverbanks. Suchomimus, with its long narrow snout filled with conical teeth, appears adapted for a fish-based diet as well. Evidence suggests that some hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) may have been strong swimmers, possibly using their powerful tails and webbed feet to navigate lakes and rivers. Paleontologists have also identified possible semi-aquatic behavior in certain theropods based on isotopic analyses of their teeth, suggesting they obtained a significant portion of their diet from aquatic sources. Despite these water-friendly adaptations, it’s important to emphasize that these dinosaurs remained fundamentally terrestrial animals that exploited aquatic resources rather than fully committed marine creatures.

Birds: The Dinosaurs That Conquered Water

In a fascinating evolutionary twist, birds—which are technically avian dinosaurs—have achieved what their non-avian dinosaur ancestors never did: mastery of aquatic environments. Modern birds like penguins, cormorants, and diving-petrels have evolved remarkable adaptations for marine life, including waterproof feathers, specialized breathing systems, and flippers modified from wings. Penguins, in particular, have become so specialized that they essentially “fly” underwater with wing-derived flippers, diving to impressive depths to hunt fish and squid. This aquatic success story represents the ultimate irony in the question of whether dinosaurs lived in oceans—while non-avian dinosaurs never truly conquered marine environments, their direct descendants eventually did. The evolutionary journey from terrestrial dinosaurs to aquatic birds spans over 150 million years, demonstrating the remarkable plasticity of the dinosaur lineage and its ability to eventually adapt to almost every environment on Earth, including the oceans.

Why Didn’t Dinosaurs Colonize the Oceans?

The absence of fully marine dinosaurs raises intriguing questions about evolutionary constraints and ecological competition. One likely explanation involves timing and ecological niches – by the time dinosaurs evolved, marine reptiles had already established dominance in oceanic ecosystems. These groups had developed specialized adaptations for marine life over millions of years, potentially leaving few available niches for dinosaurs to exploit. Dinosaur physiology may have presented another barrier – their respiratory systems and metabolic requirements, while efficient for active terrestrial life, might have required extensive modification for deep-diving marine existence. Additionally, the successful terrestrial radiation of dinosaurs likely created evolutionary momentum favoring further specialization in land environments rather than dramatic habitat shifts. The few dinosaurs that did develop semi-aquatic adaptations, like Spinosaurus, primarily exploited freshwater environments where competition with marine reptiles was reduced. These factors collectively help explain why dinosaurs remained primarily terrestrial throughout their long evolutionary history.

The Coastal Connection

While true dinosaurs didn’t live in oceans, many species undoubtedly interacted with coastal environments. Fossil trackways have revealed dinosaur footprints preserved in ancient shoreline sediments, indicating these animals frequently traversed beach zones. Coastal dinosaurs likely exploited the rich resources of shoreline ecosystems, feeding on beached marine organisms, shoreline plants, or small animals in tidal areas. Some may have scavenged carcasses washed ashore, while others possibly hunted prey that ventured onto beaches. The fossil record occasionally presents tantalizing evidence of dinosaurs that died near shores and were subsequently washed out to sea, where their remains became preserved in marine sediments. These fossils don’t indicate marine lifestyles but rather document post-mortem transport into ocean environments. Coastal zones likely served as important ecological interfaces where terrestrial dinosaurs could access marine resources without needing full aquatic adaptations.

Modern Parallel: Reptiles at the Water’s Edge

Examining modern reptiles provides valuable insights into the ecological boundaries that likely influenced dinosaur evolution. Today’s reptiles demonstrate varying degrees of aquatic adaptation without fully committing to marine life. Marine iguanas of the Galapagos Islands feed underwater on algae but return to land for warmth and reproduction, representing a fascinating middle ground between terrestrial and marine existence. Saltwater crocodiles, Earth’s largest living reptiles, excel in both freshwater and saltwater environments but still require land for nesting and basking. These contemporary examples suggest potential limitations that may have affected dinosaurs’ ability to fully transition to marine life. Physiological constraints related to temperature regulation, egg-laying requirements, and respiratory adaptations likely created evolutionary thresholds that non-avian dinosaurs never crossed. The modern examples highlight how even highly water-adapted reptiles maintain crucial connections to terrestrial environments, providing a framework for understanding why dinosaurs remained fundamentally land animals despite some species developing limited aquatic capabilities.

What Fossil Evidence Tells Us

The fossil record provides our clearest window into ancient ecological relationships and habitat preferences. Despite over 150 years of intensive dinosaur fossil collection worldwide, paleontologists have never discovered dinosaur remains with the suite of adaptations necessary for a fully marine lifestyle. While occasional dinosaur fossils appear in marine sediments, taphonomic evidence (study of how organisms decay and become fossilized) typically indicates these represent carcasses washed out to sea rather than animals that lived there. Contrastingly, marine reptile fossils consistently display clear aquatic adaptations: hydrofoil-like limbs, specialized vertebral structures for swimming, and modified skull features for underwater feeding. The absence of such adaptations in dinosaur fossils, despite the excellent preservation potential of marine environments, strongly supports the conclusion that dinosaurs remained terrestrial throughout their evolutionary history. When combined with positive evidence of terrestrial adaptations in all known dinosaur groups, the fossil record presents a compelling case that true dinosaurs never evolved to live in oceans.

The Legacy of Marine Reptiles and Dinosaurs

The extinction event that eliminated non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous period approximately 66 million years ago also claimed the dominant marine reptile groups, including mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. This simultaneous disappearance created ecological opportunities that were eventually filled by mammals returning to the sea, leading to the evolution of whales, dolphins, and seals. Meanwhile, surviving avian dinosaurs—birds—continued to diversify, with some lineages independently evolving aquatic and marine adaptations. The parallel evolution of marine birds and mammals following the disappearance of Mesozoic marine reptiles demonstrates the persistent ecological pressures favoring large vertebrate predators in ocean ecosystems. Today’s oceans, populated by mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles like sea turtles, represent the latest configuration in a long evolutionary succession of marine vertebrate communities. Understanding the distinction between dinosaurs and marine reptiles helps clarify this evolutionary narrative while highlighting the remarkable adaptability of vertebrate life throughout Earth’s history.

Conclusion

The question “Did any dinosaurs live in the ocean?” leads us to a fascinating exploration of prehistoric ecology and taxonomy. The scientific evidence conclusively demonstrates that dinosaurs, strictly defined, were terrestrial animals that never fully adapted to oceanic life. The marine creatures often mistakenly identified as dinosaurs—ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs—represent separate reptilian lineages that evolved aquatic adaptations independently from the dinosaur line. While some dinosaurs like Spinosaurus showed unprecedented semi-aquatic features, these adaptations were primarily for freshwater environments rather than open oceans. Ironically, it would be the avian dinosaurs—birds—that eventually conquered marine environments millions of years after their non-avian relatives disappeared. This evolutionary story underscores the importance of scientific precision in classification while highlighting the remarkable diversity of reptilian adaptation during the Mesozoic Era, both on land and in the sea.