The ancient world was a complex ecosystem teeming with diverse life forms, each carving out their niche in the prehistoric landscape. Among these creatures, dinosaurs and crocodilians stand out as iconic representatives of the Mesozoic Era. While dinosaurs have captured our imagination through countless movies and museum exhibits, crocodilians have persisted virtually unchanged into the modern era. But how did these powerful reptiles interact during their shared time on Earth? Did they compete directly for resources and territory, or did they establish distinct ecological roles that allowed for coexistence? This article explores the fascinating relationship between dinosaurs, crocodilians, and other reptiles during their overlapping reign, examining how these magnificent creatures divided or competed for space in their ancient world.

The Timeline of Coexistence

Dinosaurs and crocodilians shared the Earth for an extensive period, with their coexistence spanning much of the Mesozoic Era (252-66 million years ago). Crocodilians evolved from archosaurs during the Late Triassic period, roughly 230 million years ago, while dinosaurs had already begun their evolutionary journey slightly earlier. This lengthy period of concurrent existence—over 160 million years—provided ample opportunity for ecological interactions between these groups. Throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, both dinosaurs and crocodilians underwent significant evolutionary diversification, adapting to various environments and environmental niches. This shared timeline makes questions about competition and coexistence particularly relevant, as both groups would have faced similar environmental challenges and resource limitations throughout their evolutionary history.

Ecological Niches: How Space Was Divided

One of the primary reasons dinosaurs and crocodilians could coexist was their occupation of different ecological niches, reducing direct competition. Dinosaurs diversified into numerous terrestrial roles—from massive herbivorous sauropods browsing tall vegetation to agile bipedal predators like Velociraptor hunting in open plains. Meanwhile, crocodilians primarily established themselves in semi-aquatic environments, becoming specialized predators in rivers, lakes, and coastal regions. This ecological separation allowed both groups to thrive without extensive direct competition for the same resources. The principle of niche partitioning was especially evident in their feeding behaviors, with most crocodilians developing ambush-hunting strategies near water, while predatory dinosaurs typically employed pursuit-hunting in more terrestrial settings. This division of ecological space represents a fundamental aspect of how these reptilian giants managed to share the Mesozoic world.

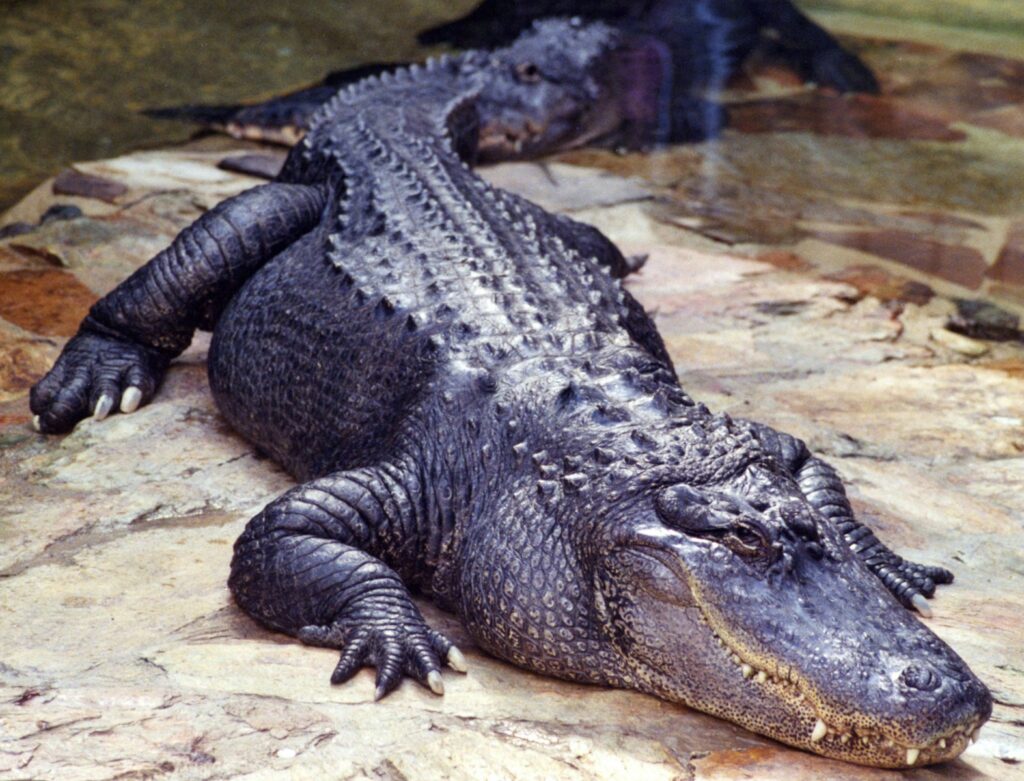

The Semi-Aquatic Advantage of Crocodilians

Crocodilians possessed a significant competitive advantage through their semi-aquatic lifestyle, which most dinosaurs did not share. Their streamlined bodies, powerful swimming tails, and specialized physiological adaptations allowed them to exploit aquatic environments effectively. These adaptations included salt glands for marine species, specialized lung capacity for remaining submerged, and sensory organs like pressure receptors that could detect movement in water. By dominating waterways and shorelines, crocodilians carved out a niche that remained relatively unthreatened by dinosaurian competition. This aquatic specialization also provided crocodilians with unique hunting opportunities, allowing them to ambush terrestrial dinosaurs that came to water sources to drink. The semi-aquatic lifestyle eventually proved crucial for crocodilian survival through the end-Cretaceous extinction event, as aquatic ecosystems were somewhat buffered from the catastrophic effects that eliminated all non-avian dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs vs. Crocodilians: Size Comparisons

Size disparities between dinosaurs and crocodilians likely influenced their competitive interactions and spatial distribution. While some extinct crocodilians reached impressive dimensions—Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus grew to estimated lengths of 11-12 meters—they were still dwarfed by the largest dinosaurs. Sauropods like Argentinosaurus could reach lengths of 30-40 meters and heights, allowing them to browse vegetation far beyond the reach of any crocodilian. This size differential meant that adult specimens of many dinosaur species were simply too large to be threatened by even the largest crocodilians. Conversely, smaller dinosaur species likely needed to remain vigilant near waterways where large crocodilians lurked. The size relationship between these groups wasn’t static throughout the Mesozoic; during the Late Cretaceous, some crocodilians evolved into massive sizes precisely when large theropod dinosaurs were becoming less common in certain ecosystems, suggesting a possible response to reduced competition or increased opportunity in the predator niche.

Terrestrial Crocodilians: The Exceptions to the Rule

Not all prehistoric crocodilians confined themselves to aquatic environments, and these terrestrial forms potentially engaged in more direct competition with dinosaurs. During the Triassic and early Jurassic periods, several crocodylomorph lineages evolved fully terrestrial lifestyles, including the notosuchians and sebecids, which had longer limbs positioned more directly under their bodies for efficient land movement. These terrestrial crocodilians often possessed heterodont dentition (different tooth types) similar to mammals, suggesting specialized feeding strategies that might have put them in competition with certain dinosaur groups. Particularly in South America during the Cretaceous period, notosuchians diversified into numerous ecological roles, including potential herbivores and specialized carnivores. This terrestrial adaptation placed these crocodilian relatives in more direct spatial competition with dinosaurs, requiring more significant niche partitioning through differences in diet, activity patterns, or geographic distribution to facilitate coexistence.

Competition During Different Life Stages

The competitive dynamics between dinosaurs and crocodilians likely shifted dramatically across different life stages. Juvenile dinosaurs, particularly from larger species, would have been vulnerable to predation by crocodilians when they ventured near water. This vulnerability created a competitive disadvantage for young dinosaurs in riparian (riverside) environments where crocodilians dominated. Conversely, hatchling and juvenile crocodilians faced potential predation from terrestrial dinosaurs, especially smaller theropods that could hunt effectively in shallow water margins. These stage-dependent interactions meant that spatial competition was not uniform throughout the animals’ lives. Evidence from modern ecosystems suggests that this dynamic might have influenced nesting site selection, with dinosaurs potentially avoiding nesting near crocodilian-dominated waterways and crocodilians seeking protected areas for their reproduction, creating a mosaic of spatial partitioning based on reproductive needs.

Fossil Evidence of Direct Interactions

Paleontological discoveries have provided tantalizing glimpses of direct interactions between dinosaurs and crocodilians. Particularly compelling are fossils showing evidence of predation or scavenging, such as crocodilian tooth marks on dinosaur bones or, conversely, dinosaur remains in the stomach contents of fossilized crocodilians. One famous example comes from the Kem Kem beds of Morocco, where fossils suggest interactions between the massive crocodilian Sarcosuchus and dinosaurs like Spinosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus. Similarly, the massive Late Cretaceous crocodilian Deinosuchus has been associated with bite marks on dinosaur fossils, indicating it preyed upon dinosaurs that ventured too close to its aquatic domain. These fossil findings, while relatively rare, confirm that direct competition and predatory relationships did occur between these groups. However, the limited frequency of such evidence compared to the abundance of both animal types suggests that widespread, continuous competition was not the norm.

Regional Variations in Competition

The intensity of competition between dinosaurs and crocodilians varied significantly across different geographic regions and habitats. In river delta environments and coastal plains, where crocodilian diversity was typically highest, spatial competition would have been more pronounced, particularly for access to prime hunting territories along waterways. Conversely, in inland areas distant from major water bodies, dinosaurs could dominate with minimal crocodilian competition. This geographic variation created a patchwork of competitive intensity across the Mesozoic landscape. Paleobiogeographic studies indicate that certain regions, like the Late Cretaceous ecosystems of what is now Madagascar and South America, hosted particularly diverse assemblages of both groups, suggesting evolved mechanisms for coexistence. Climate also played a crucial role in this regional variation, with seasonal dry periods potentially intensifying competition around remaining water sources, while wet seasons allowed for greater niche separation as resources became more abundant and widely distributed.

Competition with Other Reptile Groups

Beyond the dinosaur-crocodilian dynamic, various other reptile groups factored into the competitive landscape of the Mesozoic. Pterosaurs, though not dinosaurs but rather flying reptilian relatives, occupied aerial niches and competed minimally with either dinosaurs or crocodilians for physical space, though they may have competed for food resources at shorelines or carrion sites. Marine reptiles like plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and mosasaurs dominated oceanic environments, occasionally competing with coastal or marine crocodilians but rarely with dinosaurs. Smaller reptiles, including lizards, tuataras, and early snakes, evolved to exploit microhabitats and resource opportunities too small to interest most dinosaurs or crocodilians. The presence of these additional reptilian groups created a complex competitive ecosystem with multiple layers of spatial partitioning. This diversity ultimately contributed to the remarkable richness of Mesozoic ecosystems, where numerous reptile lineages coexisted through specialization rather than through direct competition for identical resources.

The Impact of Changing Environments

Throughout the Mesozoic Era, Earth’s environments underwent significant transformations that influenced competitive dynamics between dinosaurs and crocodilians. Sea level fluctuations dramatically altered coastlines and inland waterways, alternately expanding and contracting habitable zones for semi-aquatic crocodilians. Climate shifts, particularly warming periods during the Jurassic and early Cretaceous, favored crocodilian expansion into higher latitudes where they could compete with dinosaurs in previously inaccessible territories. Continental drift gradually separated populations, leading to regional specialization and altered competitive landscapes on different landmasses. During periods of environmental stress, such as volcanic activity or asteroid impacts, the resulting ecological disruptions temporarily shifted competitive advantages between these groups. These environmental changes rarely affected both groups equally—crocodilians generally showed greater resilience to certain types of environmental disruption due to their semi-aquatic lifestyles and physiological adaptations, while dinosaurs demonstrated superior adaptability to terrestrial habitat changes.

Modern Analogs: Crocodilians and Mammals Today

The relationship between modern crocodilians and mammals offers insights into how dinosaurs and ancient crocodilians might have interacted. In current ecosystems, crocodilians occupy niches somewhat similar to their Mesozoic ancestors, primarily dominating as apex predators in aquatic environments while ceding terrestrial dominance to mammals, the ecological successors to dinosaurs. Observations of Nile crocodiles competing with large mammals like hippos for space in African waterways demonstrate how size and aggression create zones of exclusion and respect between different animal groups. Research in the Florida Everglades shows how American alligators and various mammal species establish temporal and spatial partitioning to minimize direct competition. The competitive outcomes typically depend on the specific environment; crocodilians dominate in water, while mammals control terrestrial zones, creating boundary areas where competition intensifies. These modern patterns suggest that Mesozoic crocodilians and dinosaurs likely established similar “zones of influence” with dynamic boundaries that shifted based on seasonal conditions, individual size, and specific habitat features.

Why Crocodilians Survived While Dinosaurs Perished

The end-Cretaceous mass extinction 66 million years ago eliminated all non-avian dinosaurs while allowing crocodilians to survive, fundamentally altering their competitive relationship. This extinction disparity likely resulted from several factors related to their different ecological adaptations. Crocodilians possessed physiological advantages, including ectothermic metabolism that allowed them to survive long periods without food, a crucial adaptation during the resource-scarce aftermath of the asteroid impact. Their semi-aquatic lifestyle provided buffers against extreme temperature fluctuations and access to aquatic food webs that remained somewhat intact even as terrestrial ecosystems collapsed. Additionally, crocodilians had specialized feeding adaptations that allowed dietary flexibility, including scavenging capabilities that proved advantageous during ecosystem disruption. The relatively smaller body size of surviving crocodilian lineages compared to many dinosaur species meant lower food requirements during the resource-limited post-impact world. This differential survival fundamentally reshaped Earth’s ecosystems, eliminating much of the spatial competition that had existed between these groups and allowing mammals to rise into many niches previously occupied by dinosaurs.

Lessons from Prehistoric Coexistence

The long coexistence of dinosaurs and crocodilians offers valuable insights into how seemingly competitive species can share environments through ecological specialization. Rather than engaging in constant direct competition, these groups largely evolved complementary adaptations that minimized spatial overlap and resource conflicts. This pattern of niche partitioning represents a fundamental ecological principle that continues to shape modern ecosystems. The dinosaur-crocodilian relationship demonstrates how competition itself serves as an evolutionary driver, pushing species toward specialization rather than confrontation. For paleontologists and ecologists, this prehistoric example highlights the importance of considering multiple dimensions of ecological separation—not just geographic space, but also differences in diet, activity patterns, microhabitat preferences, and life history strategies. Understanding how these ancient reptiles divided their world provides a valuable framework for interpreting modern conservation challenges, particularly in predator-rich ecosystems where similar mechanisms of coexistence continue to operate.

Conclusion

The relationship between dinosaurs and crocodilians throughout the Mesozoic Era was characterized more by coexistence through niche specialization than by constant competition. While these impressive reptiles certainly interacted and occasionally competed directly for resources, they largely evolved to exploit different aspects of their shared environments. Crocodilians dominated aquatic habitats with specialized adaptations for semi-aquatic lifestyles, while dinosaurs diversified into numerous terrestrial niches. Their long coexistence demonstrates nature’s tendency toward ecological partitioning rather than continuous competitive exclusion. When we marvel at both the fossilized remains of extinct dinosaurs and the living crocodilians that have persisted virtually unchanged for millions of years, we’re witnessing the results of an ancient balancing act—one that allowed these magnificent reptiles to share a planet for over 160 million years through specialization, adaptation, and the efficient division of ecological space.