For decades, our collective imagination of dinosaurs has been dominated by the iconic roars depicted in movies like Jurassic Park. These fearsome bellows have become so ingrained in popular culture that we rarely question their accuracy. However, recent scientific research has begun to challenge these long-held assumptions about dinosaur vocalizations. Paleontologists and biologists studying the anatomy of these prehistoric creatures have uncovered compelling evidence suggesting that dinosaurs likely sounded very different from the thunderous roars we’ve come to expect. This fascinating development in our understanding of dinosaur biology invites us to reimagine how these magnificent creatures might have communicated and interacted with their environment millions of years ago.

The Hollywood Roar: How Pop Culture Shaped Our Perception

The portrayal of dinosaurs in popular media has significantly influenced our perception of how these ancient creatures sounded. When Jurassic Park debuted in 1993, sound designers created the T. rex’s iconic roar by blending sounds from various modern animals, including tigers, alligators, and elephants. This creative sound engineering, while dramatically effective, was based more on artistic interpretation than scientific evidence. For generations since, children and adults alike have associated dinosaurs with these powerful, mammal-like roars. This widespread cultural programming has been so effective that even in scientific discussions, we often unconsciously default to these familiar soundscapes when imagining dinosaur vocalizations. The challenge for paleontologists has been to separate these ingrained fictional portrayals from evidence-based reconstructions of dinosaur sounds.

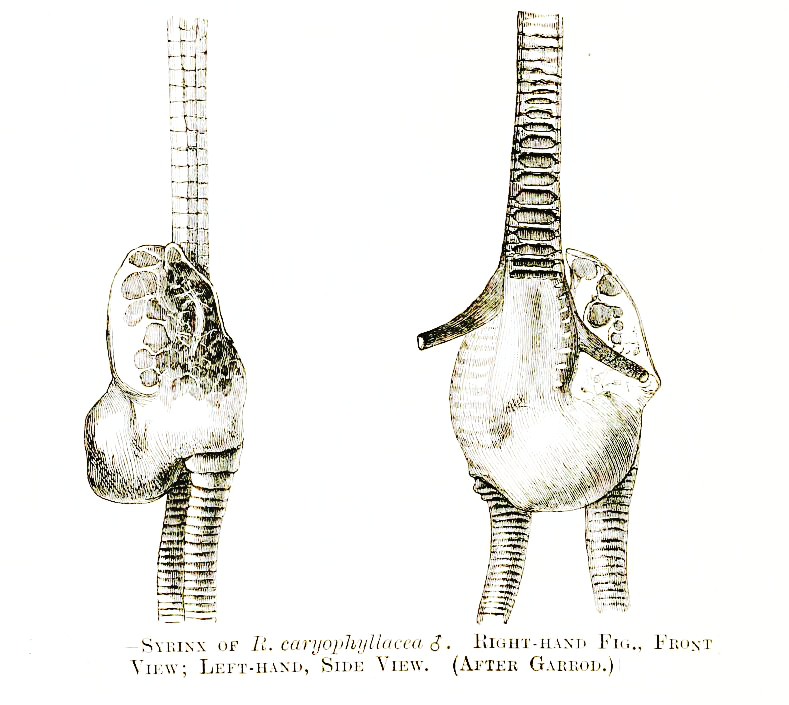

Anatomical Evidence: What Dinosaur Throats Tell Us

Research into dinosaur vocalization begins with examining their anatomical structures, particularly those related to sound production. Unlike mammals, which have a larynx (voice box), birds and reptiles possess a syrinx – a vocal organ located at the base of the trachea. Since birds are direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs, many scientists believe dinosaurs likely had syrinx-like structures rather than larynges. Fossil evidence of these structures is extremely rare due to their soft tissue nature, but a 2016 discovery of a fossilized syrinx in a Late Cretaceous bird provided valuable insights. Additionally, studies of dinosaur skull anatomy, particularly the structures around the nasal passages and sinuses, suggest they could have produced resonant sounds, though likely different from mammalian roars. The length and structure of the dinosaur’s neck would also have influenced sound production, potentially creating unique acoustic properties unlike anything we hear from modern animals.

The Bird Connection: Clues from Modern Descendants

The evolutionary relationship between dinosaurs and birds offers one of our most promising pathways to understanding dinosaur vocalizations. Modern birds, as the direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs, provide living models for how dinosaur sound production might have worked. Birds produce their diverse vocalizations using a syrinx, which allows for complex sounds including songs, calls, and even mimicry in some species. The discovery that many dinosaurs, particularly theropods, had hollow air-filled bones similar to those in modern birds further strengthens this connection. These pneumatic bones could have functioned as resonating chambers, enhancing and modifying sounds. Some paleontologists theorize that certain dinosaur species, especially those most closely related to birds, might have been capable of relatively complex vocalizations – perhaps not singing like songbirds, but potentially producing more nuanced sounds than simple hisses or moans. This bird-dinosaur connection suggests that at least some dinosaur species were likely more vocally sophisticated than previously thought.

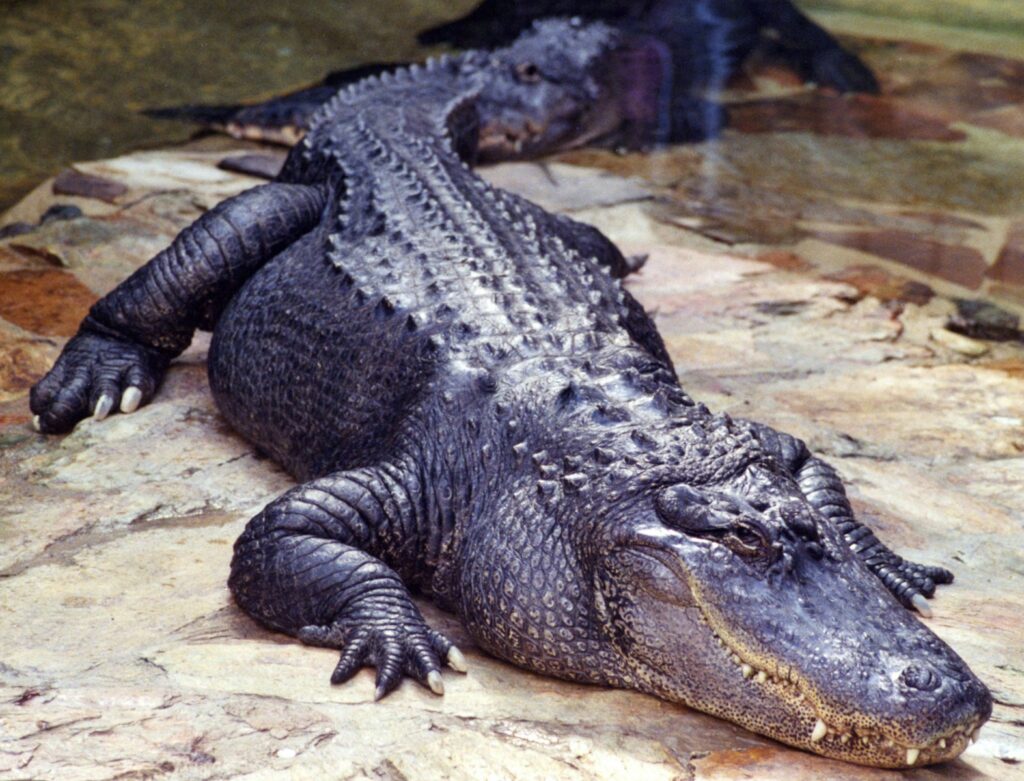

Closed-Mouth Vocalization: The Crocodile Model

Another compelling theory about dinosaur sounds comes from studying their other living relatives: crocodilians. A 2016 study published in the journal “Evolution” suggested that many dinosaurs might have used closed-mouth vocalization similar to modern crocodiles, alligators, and certain bird species. This form of vocalization creates low-frequency sounds by vibrating air in the throat while keeping the mouth closed, resulting in a resonant, rumbling sound rather than an open-mouthed roar. This method is used by modern crocodilians when they bellow to mark territory or during mating displays. The study examined 52 archosaur species (the group containing birds, crocodilians, and dinosaurs) and found that closed-mouth vocalization evolved independently numerous times, suggesting it was likely present in some dinosaur lineages. This theory is particularly relevant for large dinosaurs, as the resonant chambers in their bodies could have amplified these low-frequency sounds, potentially allowing them to communicate over significant distances without expending the energy required for loud roars.

Infrasound: Communication Beyond Human Hearing

One fascinating possibility is that some dinosaurs, particularly the largest sauropods like Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus, may have communicated using infrasound – sound frequencies below the range of human hearing. Modern elephants are known to use infrasound to communicate over distances of several kilometers, and the enormous body size of many dinosaurs would have made them physically capable of producing such low-frequency sounds. The massive nasal passages and hollow cranial crests of some dinosaur species could have served as resonating chambers for these low-frequency vocalizations. This theory is supported by the discovery that the elaborate crests of hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) contained complex nasal passages that could have functioned as sound-producing and amplifying structures. If dinosaurs did use infrasound, they could have maintained communication across vast territories without humans ever being able to hear them, even if we had been present in the Mesozoic era. This adds an intriguing “silent” dimension to how we envision dinosaur social behavior.

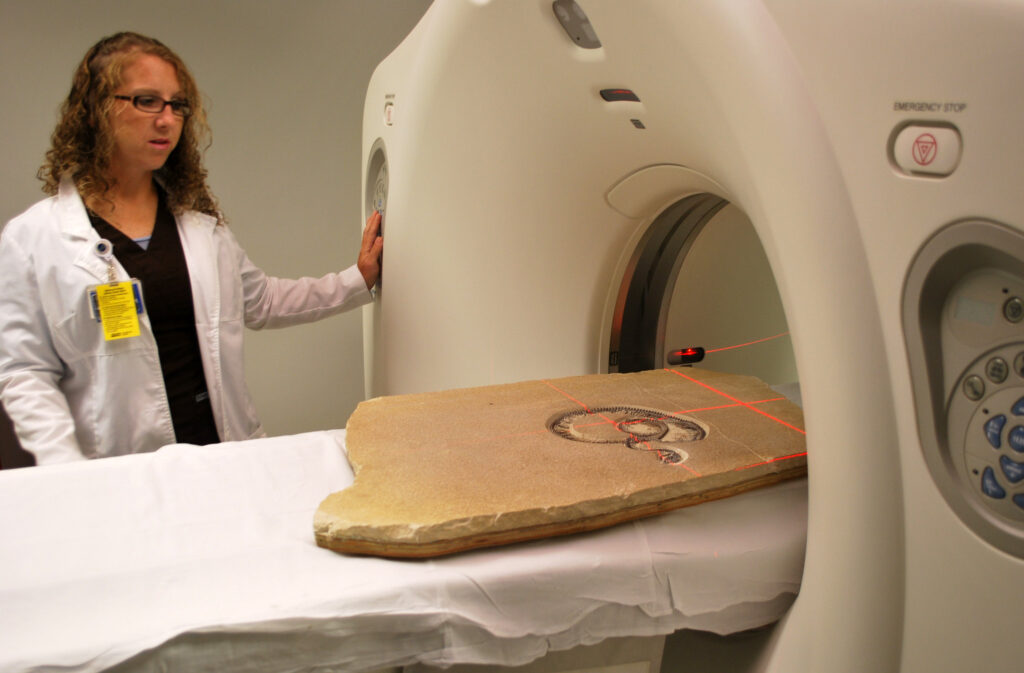

Digital Reconstructions: Using Technology to Hear the Past

Advances in computer modeling and acoustic technology have allowed scientists to create more accurate reconstructions of potential dinosaur vocalizations. By combining CT scans of dinosaur skulls with acoustic modeling software, researchers can simulate how air might have moved through these ancient structures and what sounds could have resulted. One notable example is the work done with Parasaurolophus, a hadrosaur with an elaborate hollow crest extending from its skull. Computer models suggest this crest functioned as a resonating chamber, potentially producing deep, trumpet-like sounds rather than roars. Similar work has been done with other dinosaur species, using their fossilized remains to create digital models of their vocal tracts. These reconstructions suggest a wide range of possible sounds, from low-frequency rumbles in large sauropods to higher-pitched calls in smaller theropods. While these models necessarily involve some speculation, they represent our best scientific attempts to “hear” dinosaurs based on their anatomical structures.

Hadrosaur Headgear: Nature’s Prehistoric Trumpets

Hadrosaurs, commonly known as duck-billed dinosaurs, possess some of the most compelling evidence for unique dinosaur vocalizations. Species like Parasaurolophus, Corythosaurus, and Lambeosaurus had elaborate hollow crests extending from their skulls, containing complex nasal passages that looped through these structures before connecting to the airway. When researchers created physical and digital models of these passages, they discovered these crests could have functioned essentially as natural trumpets or trombones. The sound produced would have been deep and resonant, similar to brass instruments rather than mammalian roars. Different hadrosaur species had differently shaped crests, suggesting each might have produced its own distinctive sound. This variation could have enabled species recognition, mate selection, and hierarchical communication within herds. The investment these dinosaurs made in growing these elaborate structures suggests vocal communication was significant to their social lives, perhaps more so than in many other dinosaur groups.

The Quieter Dinosaurs: Were Some Species Relatively Silent?

Not all dinosaurs were likely vocal performers, and some species may have been relatively quiet compared to others. Many modern reptiles, such as certain lizards and turtles, make few vocalizations, primarily hissing or making breathing sounds when threatened. Some dinosaur groups, particularly those without specialized sound-producing anatomy like elaborate crests or evidence of air sacs, may have similarly been limited in their vocal repertoire. Ceratopsians like Triceratops, for instance, show less evidence of specialized sound-producing structures compared to hadrosaurs. Instead, their elaborate frills and horns suggest visual display may have been more important for their communication. Similarly, armored dinosaurs like ankylosaurs and stegosaurs may have relied more on visual signals and physical displays rather than complex vocalizations. This suggests a diverse communication landscape across different dinosaur groups, with some being relatively vocal while others may have been comparatively silent, using alternative methods to communicate with conspecifics.

Social Context: How the Environment Shaped Dinosaur Sounds

The habitats and social structures of different dinosaur species likely influenced the evolution of their vocal abilities. Dinosaurs living in densely forested environments, where visibility was limited, may have relied more heavily on vocalizations to communicate with group members compared to those inhabiting open plains. Evidence suggests that many dinosaur species were social animals living in herds or family groups, which would have created evolutionary pressure for effective communication systems. Different vocalizations might have served various purposes – from alarm calls warning of predators to territorial announcements or mating displays. The size of dinosaur territories and typical group structures would have influenced optimal sound frequencies and volumes. For instance, herd-dwelling dinosaurs might have needed distinctive calls to maintain group cohesion, while predatory species might have benefited from stealthier communication methods. Understanding these ecological contexts helps paleontologists develop more nuanced theories about dinosaur vocalizations beyond simple questions of mechanical production.

Beyond Vocalizations: Alternative Communication Methods

Sound production was likely just one component of dinosaur communication systems. Many modern animals use multiple channels to communicate, and dinosaurs probably did the same. Visual displays would have been particularly important, as evidenced by the elaborate frills, crests, horns, and color patterns suggested by fossil evidence. Physical displays such as head-bobbing, tail-whipping, or stomping may have complemented or substituted for vocal communication in many contexts. Some dinosaurs may have used infrasonic communication through ground vibrations, similar to how elephants can detect the footfalls of other elephants over long distances. Chemical communication through scent marking was likely important as well, particularly for territorial species. Recent studies into the olfactory bulbs of dinosaur brains suggest many species had a well-developed sense of smell. This multi-modal approach to communication would have created a rich and complex social environment far beyond what can be captured by focusing solely on potential roars or calls.

Dinosaur Sounds Across the Ages: Evolutionary Changes

Dinosaur vocalizations likely evolved significantly over their 165-million-year reign on Earth. Early dinosaurs from the Triassic period probably had vocalization capabilities similar to their archosaur relatives, capable of hisses, grunts, and perhaps closed-mouth resonant sounds. As dinosaurs diversified throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, their vocal abilities likely became more specialized and varied between different lineages. The evolution of larger body sizes in some groups would have shifted vocal frequencies lower, while the development of specialized structures like hollow crests in hadrosaurs created new sound-producing possibilities. The theropod lineage that eventually led to birds showed increasing sophistication in sound production, culminating in the highly advanced syrinx of modern birds. This evolutionary progression suggests that if we could travel back in time to different periods of the Mesozoic era, the soundscape would be noticeably different in each age, reflecting the changing diversity and specialization of dinosaur species. This timeline of vocal evolution provides a fascinating dimension to our understanding of dinosaur adaptation and speciation.

Implications for Dinosaur Behavior and Intelligence

The complexity of dinosaur vocalization systems has significant implications for our understanding of their behavior and cognitive abilities. Species with more sophisticated communication capabilities generally exhibit more complex social behaviors and problem-solving skills. The evidence for varied and potentially complex vocalizations in some dinosaur groups suggests these animals may have had richer social lives than previously thought. Communication systems requiring distinct calls for different situations – warnings, mating displays, territorial claims, or coordinating group movements – imply a level of cognitive processing beyond basic instinctual responses. This aligns with recent research suggesting some dinosaurs, particularly theropods and certain ornithischians, had relatively large brain-to-body ratios compared to reptiles. The evolution of complex communication systems would have both required and further driven cognitive development. While we should be careful not to anthropomorphize dinosaurs, the emerging picture suggests at least some species possessed intelligence and social complexity that would surprise many people who think of them merely as primitive reptiles.

Continuing Research: How Modern Science Is Clarifying the Picture

The field of dinosaur vocalization research continues to advance with new technologies and methodologies. CT scanning technology has become increasingly sophisticated, allowing researchers to create more detailed models of dinosaur skull anatomy, including nasal passages and potential resonating chambers. Advances in acoustic modeling software enable more accurate simulations of how these structures might have produced and modified sounds. Comparative studies with modern birds and crocodilians provide increasingly detailed insights into the vocal mechanisms of archosaurs. New fossil discoveries, particularly of the rarely preserved throat regions or exceptionally preserved specimens showing soft tissue impressions, occasionally provide direct evidence related to sound production. The growing field of paleoacoustics combines aspects of paleontology, physics, and biology to create increasingly refined theories about prehistoric soundscapes. As this research continues, our understanding of dinosaur vocalizations will become more nuanced and evidence-based, though the exact sounds of dinosaurs may remain somewhat speculative without the ability to observe living specimens.

Conclusion: Reimagining the Sounds of the Prehistoric World

As we continue to uncover new evidence about dinosaur anatomy and biology, we’re forced to reimagine many aspects of these fascinating creatures, including how they sounded. The thunderous roars popularized by Hollywood likely bear little resemblance to the actual vocalizations of most dinosaur species. Instead, the prehistoric world was probably filled with a diverse soundscape of low-frequency rumbles, closed-mouth bellows, resonant calls through elaborate head crests, and perhaps even bird-like vocalizations from some theropods. This revised understanding of dinosaur sounds doesn’t diminish their majesty; rather, it adds another layer of fascinating complexity to these extraordinary animals that dominated Earth for over 160 million years. By piecing together anatomical evidence, using modern analogs, and employing advanced technology, scientists continue to bring us closer to hearing the true voices of the distant past, giving us an increasingly accurate window into a world long gone.