When we look at the fossil record of dinosaurs, we’re confronted with some of evolution’s most spectacular experiments. From the dramatic three-horned face of Triceratops to the imposing sail of Spinosaurus, prehistoric reptiles evolved remarkable ornaments and defensive structures that continue to captivate scientists and the public alike. These extraordinary anatomical features weren’t merely for show – they served crucial biological functions including species recognition, thermoregulation, defense against predators, and sexual selection. The diversity of these adaptations gives us a glimpse into the complex ecosystems of the Mesozoic Era and reminds us that nature’s creativity knows few bounds.

The Evolution of Dinosaur Ornamentation

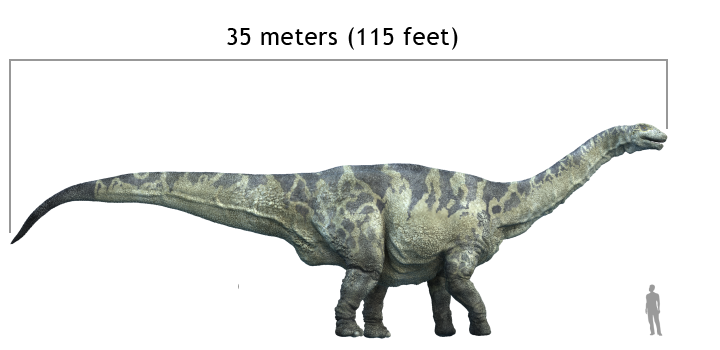

The development of horns, spikes, and sails in dinosaurs represents one of evolution’s most fascinating pathways, emerging independently across multiple dinosaur lineages. These distinctive features didn’t appear suddenly but evolved gradually over millions of years through natural selection processes. Fossil evidence suggests that many of these ornamental structures became more elaborate over time, with early ancestors displaying more modest versions of the spectacular decorations seen in later species. This pattern of increasing ornamentation aligns with what paleontologists call Cope’s Rule – the tendency for body size and complexity to increase over evolutionary time within a lineage. Importantly, the genetic modifications that allowed for these structures demonstrate how developmental pathways can be repurposed to create entirely new anatomical features, showcasing evolution’s remarkable plasticity in generating biological novelty.

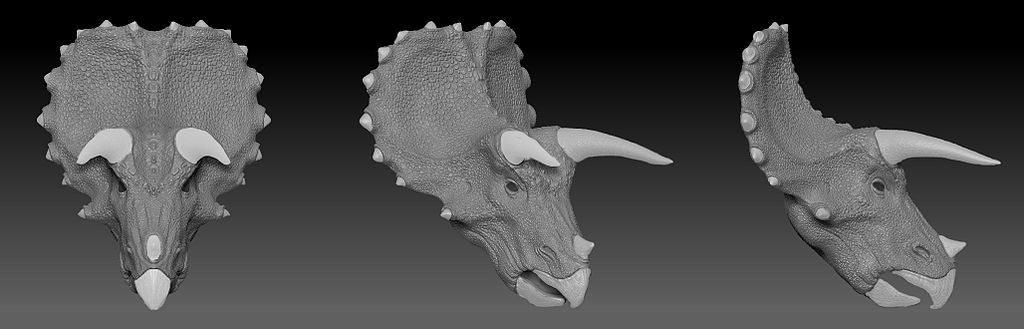

Ceratopsians: The Horn-Faced Dinosaurs

Among the most recognizable horned dinosaurs are the ceratopsians, a diverse group of herbivores that dominated the Late Cretaceous landscape. Triceratops, with its three prominent facial horns and expansive bony frill, represents the quintessential member of this family, but the ceratopsian group included numerous species with variations on this basic design. Centrosaurus featured a single large nasal horn and a frill adorned with hook-like projections, while Styracosaurus displayed a dramatic array of long spikes extending from its neck shield. Protoceratops, a smaller and more primitive relative, possessed a modest frill but lacked the impressive horns of its descendants. These varying horn and frill configurations likely evolved primarily for species recognition and sexual display, allowing individuals to identify potential mates from the same species in environments where multiple ceratopsian species coexisted.

Stegosaurus and Its Puzzling Plates

Stegosaurus stands as one of the most distinctive dinosaurs, instantly recognizable by the double row of large, alternating triangular plates along its back and the four sharp spikes on its tail (collectively known as the thagomizer). For decades, scientists debated the function of these unusual plates, proposing theories ranging from defensive armor to thermoregulatory devices. Current research supports a multi-purpose explanation, with the plates likely serving both for temperature regulation and visual display. The plates contained extensive networks of blood vessels that could have helped the animal cool down or warm up by controlling blood flow through these thin, broad structures. Additionally, the dramatic silhouette created by these plates would have made Stegosaurus instantly recognizable to others of its kind, potentially playing a role in mate selection and species identification. The tail spikes, unlike the plates, had a more straightforward defensive purpose, providing a powerful weapon against predators like Allosaurus.

Ankylosaurus: The Living Tank

Few dinosaurs were as heavily armored as Ankylosaurus, a Late Cretaceous herbivore that evolved one of nature’s most effective defensive systems. Its body was covered in bony plates called osteoderms that formed a solid protective shield, while numerous spikes protruded from its sides, providing additional protection from predators. Most impressively, Ankylosaurus wielded a massive club-like structure at the end of its tail, composed of fused vertebrae and large bony knobs, creating a formidable weapon that could deliver devastating blows to any would-be attacker. This tail club represents one of the most specialized defensive adaptations in dinosaur evolution, with studies suggesting it could generate enough force to break bones. Unlike the primarily display-oriented features of some other dinosaurs, the spiky armor of ankylosaurs evolved specifically as an anti-predator adaptation, allowing these relatively slow-moving herbivores to survive in environments dominated by large theropod predators like Tyrannosaurus rex.

Sail-Backed Dinosaurs: Spinosaurus and Ouranosaurus

Perhaps the most enigmatic ornamental structures among dinosaurs were the tall neural spine “sails” seen in dinosaurs like Spinosaurus and Ouranosaurus. Spinosaurus, the largest known carnivorous dinosaur, sported a massive sail along its back formed by greatly elongated neural spines that could reach heights of over 5 feet (1.5 meters). Similarly, the herbivorous Ouranosaurus displayed an impressive sail-like structure, though scientists debate whether it supported a true sail or a fatty hump similar to modern bison. These structures likely served multiple functions, with thermoregulation being a primary purpose – the large surface area could dissipate excess heat in hot environments or collect warmth in cooler conditions. Additionally, these dramatic sails would have made these dinosaurs appear larger and more imposing when viewed from the side, potentially intimidating rivals or predators. Recent research on Spinosaurus has revealed its semi-aquatic lifestyle, suggesting its sail might have had additional functions related to underwater movement or display while fishing.

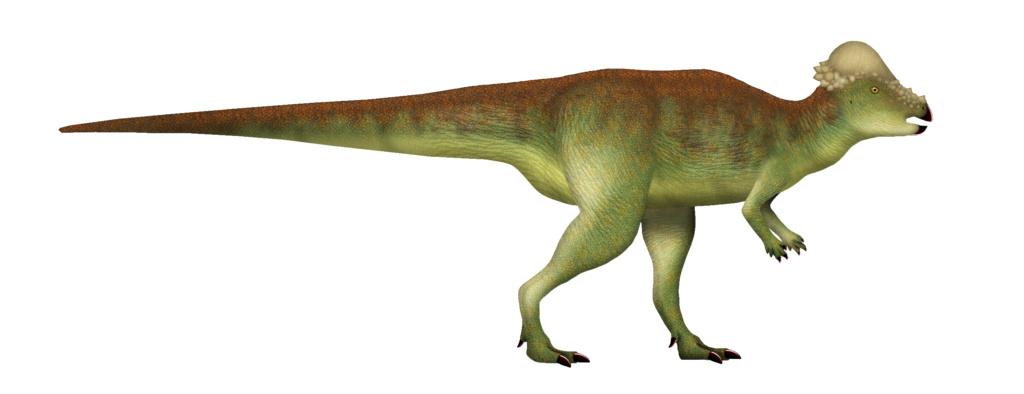

Pachycephalosaurs: The Dome-Headed Dinosaurs

While not sporting traditional horns or spikes, pachycephalosaurs developed one of the most unusual cranial structures among all dinosaurs – thick, dome-shaped skulls reinforced with up to 10 inches (25 cm) of solid bone. The most famous member of this group, Pachycephalosaurus, featured not only a dramatic dome but also ornamental knobs and spikes around the rear edge of its skull. These remarkable adaptations have long fascinated paleontologists, who initially hypothesized that pachycephalosaurs engaged in head-butting contests similar to modern bighorn sheep. However, more recent biomechanical analyses suggest that their skulls may not have withstood direct high-speed impacts, leading to alternative theories that they engaged in flank-butting behavior instead. What remains clear is that these elaborate skull modifications served some social function, likely related to establishing dominance hierarchies or competing for mates within their species.

Amargasaurus: The Bizarre Double-Spined Sauropod

Among the long-necked sauropod dinosaurs, Amargasaurus stands out for its utterly unique anatomical feature – two parallel rows of tall, narrow neural spines running down its neck and back. These spines, which could reach up to 2 feet (60 cm) in length, created a striking silhouette unlike any other known dinosaur. Paleontologists have proposed several hypotheses for their function, including the possibility that they supported a sail-like structure, formed a defensive display similar to a porcupine’s quills, or were covered with keratin sheaths to create impressive spikes. Another interesting theory suggests these spines may have been used for intraspecific combat or display, with males potentially engaging in “neck-fencing” competitions. Found in Early Cretaceous Argentina, this medium-sized sauropod demonstrates that even within well-established dinosaur body plans, evolution could produce remarkably specialized adaptations that don’t fit neatly into our understanding of other species.

Thermoregulation: Keeping Cool and Warm

Many dinosaur ornamentations likely played crucial roles in temperature regulation, a critical function for these potentially warm-blooded animals. Large-bodied dinosaurs faced significant challenges in managing body temperature, particularly in maintaining optimal brain temperature in varying environmental conditions. Structures like the frills of ceratopsians, the plates of stegosaurs, and the sails of spinosaurids provided expansive surfaces where blood vessels could dissipate excess heat or absorb warmth depending on need. By controlling blood flow to these structures, dinosaurs could effectively manage their internal temperatures without the metabolic costs of sweating or panting. This thermoregulatory function is supported by microscopic examinations of fossil structures that reveal extensive vascularization – networks of blood vessel channels that would have facilitated heat exchange. For dinosaurs living in seasonal environments with significant temperature fluctuations, these adaptations would have provided substantial evolutionary advantages by extending the range of conditions in which they could remain active and efficient.

Sexual Selection and Species Recognition

Many of the most elaborate dinosaur ornamentations likely evolved through sexual selection – the evolutionary process where certain traits become more prominent because they attract mates. Just as a peacock’s tail or a deer’s antlers serve primarily to impress potential partners, the frills, horns, and crests of many dinosaurs may have functioned as indicators of genetic quality and health. Fossil evidence suggests that some ornamental features were sexually dimorphic, meaning they differed between males and females of the same species, further supporting their role in mating displays. Additionally, these distinctive structures would have helped individuals recognize members of their own species in environments where multiple similar dinosaur types coexisted. For instance, the wide variety of horn and frill configurations among ceratopsians living in the same habitats would have prevented breeding attempts between different species, maintaining genetic boundaries. This dual function – attracting mates and ensuring appropriate species recognition – likely drove the evolution of increasingly elaborate structures over millions of years.

Defensive Adaptations Against Predators

While some ornamental structures evolved primarily for display, others served direct defensive purposes against the formidable predators of the Mesozoic Era. The tail club of ankylosaurs represents one of the clearest examples of an anti-predator weapon, capable of delivering powerful blows to attackers. Similarly, the tail spikes of stegosaurs – the so-called thagomizer – provided an effective deterrent against predators approaching from behind. For ceratopsians, the impressive facial horns could have served as defensive weapons, particularly when these herbivores adopted a charging posture similar to modern rhinoceros. Experimental studies of fossilized Triceratops horns suggest they were capable of penetrating the hide of potential predators like Tyrannosaurus rex. Even primarily display-oriented structures often had secondary defensive benefits – a Spinosaurus with its sail raised would have appeared significantly larger and more intimidating to potential threats. These various defensive adaptations illustrate the intense predatory pressures that shaped dinosaur evolution and drove the development of increasingly effective protection mechanisms.

The Debate Over Dinosaur Ornamentation

Scientific understanding of dinosaur ornamentation continues to evolve as new fossils are discovered and novel analytical techniques are applied. One of the most significant ongoing debates concerns the relative importance of different functions – whether a particular feature evolved primarily for display, defense, thermoregulation, or some combination of purposes. This question becomes particularly complex when examining extreme adaptations like the elaborate frills of ceratopsids or the neural spine sails of spinosaurids. Another contentious area involves determining whether certain ornamentations were covered with keratin sheaths, skin, or supported other soft tissues that haven’t been preserved in the fossil record. The recent discovery of exceptionally preserved specimens with skin impressions has begun to resolve some of these uncertainties, but many questions remain. Additionally, the evolutionary pathways that led to these specialized structures continue to be refined as new intermediate fossil forms fill gaps in our understanding of how these remarkable adaptations developed over millions of years.

Modern Descendants: Horns and Frills in Living Reptiles

While the dinosaurs that roamed the Mesozoic landscapes have long since vanished, their evolutionary legacy continues in modern birds – the only surviving dinosaur lineage. Interestingly, some contemporary reptiles (though not directly descended from dinosaurs) display convergent evolution of horn-like and frill-like structures reminiscent of their ancient counterparts. The frilled lizard of Australia possesses a large extensible neck frill that serves a similar intimidation purpose as the ceratopsian frill. Horned lizards of North America feature crown-like arrangements of pointed scales that provide protection similar to the horns of ceratopsians. Perhaps most striking is the casque of the cassowary, a large flightless bird whose prominent helmet-like structure on its head serves multiple functions including protection, sexual display, and possibly amplifying low-frequency sounds. These modern examples help scientists understand how similar selective pressures can produce comparable adaptations across different evolutionary lineages and time periods, providing living models for how dinosaur ornamentations might have functioned.

Reconstructing Dinosaur Appearance: Challenges and Breakthroughs

Accurately reconstructing the external appearance of ornamented dinosaurs presents significant scientific challenges, as soft tissues rarely preserve in the fossil record. For decades, scientists debated whether structures like the plates of Stegosaurus were covered in skin, keratin, or supported sail-like membranes. Recent advances in comparative anatomy, microscopic analysis of bone structure, and the discovery of exceptional fossils preserving skin impressions have dramatically improved our understanding. Examination of bone texture can reveal whether a structure was likely covered in a keratin sheath (similar to bovid horns) or supported skin and blood vessels. Additionally, modern technologies like CT scanning allow paleontologists to examine the internal structure of ornamentations, revealing blood vessel channels and growth patterns that provide clues to their function and appearance. Perhaps most exciting are the increasing discoveries of fossilized skin impressions that directly show scale patterns and soft tissue attachments, removing some of the guesswork from reconstructions and allowing for increasingly accurate depictions of these magnificent animals as they appeared in life.

Conclusion

The extraordinary array of horns, spikes, frills, and sails that adorned dinosaurs represents one of evolution’s most spectacular showcases of anatomical innovation. These structures served multiple, overlapping functions – from species recognition and mate attraction to temperature regulation and defense against predators. The sheer diversity and sometimes extreme nature of these adaptations reflect the intense selective pressures of Mesozoic ecosystems and the remarkable plasticity of vertebrate development. As paleontological methods continue to advance, our understanding of these strange and wonderful creatures grows increasingly sophisticated, yet many questions remain. What we can say with certainty is that these ornamentations were not evolutionary frivolities but critical adaptations that helped these animals thrive for over 150 million years – a testament to nature’s endless capacity for creative problem-solving through the power of natural selection.