Edmontosaurus, one of the most well-studied dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous period, was a magnificent herbivore that roamed across what is now North America. These duck-billed dinosaurs, known scientifically as hadrosaurs, left behind a remarkable fossil record that has enabled paleontologists to reconstruct their appearance, behavior, and ecological role with impressive detail. Living approximately 73 to 66 million years ago, these gentle giants witnessed the final days of the dinosaur era, browsing in vast herds along the coastal plains of the Western Interior Seaway. Their adaptability and social nature made them among the most successful dinosaurs of their time, and their abundant fossils continue to reveal new insights into prehistoric life.

Taxonomic Classification and Discovery History

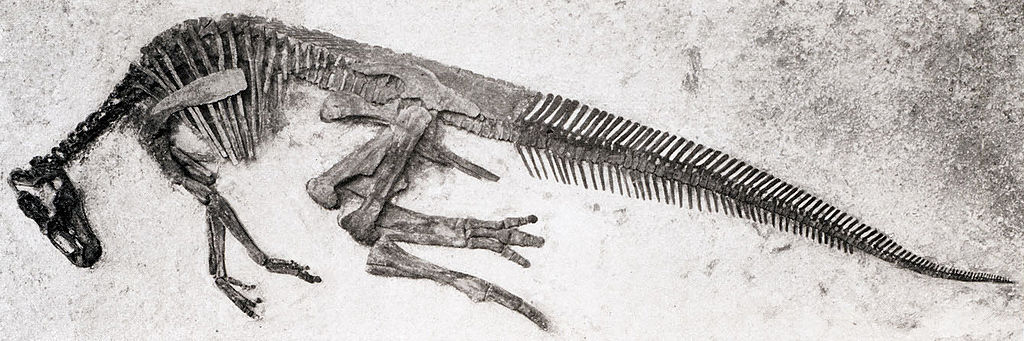

Edmontosaurus belongs to the family Hadrosauridae, commonly known as duck-billed dinosaurs, and specifically to the subfamily Saurolophinae (formerly Hadrosaurinae). The genus was first named in 1917 by Lawrence Lambe based on specimens discovered in the Edmonton Formation of Alberta, Canada, from which it derives its name. Two well-established species are recognized: Edmontosaurus regalis and Edmontosaurus annectens, though taxonomic debates have occasionally arisen regarding other potential species. The discovery history of Edmontosaurus spans more than a century, with significant specimens continually emerging from formations across western North America. Perhaps most remarkably, several “mummy” specimens with preserved skin impressions have been discovered, providing rare glimpses into the soft tissue anatomy of these prehistoric creatures.

Physical Characteristics and Size

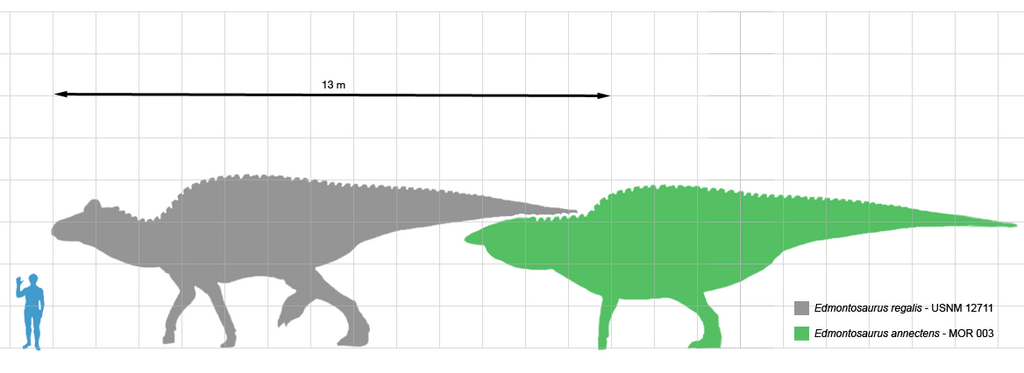

Edmontosaurus was among the largest hadrosaurs, with adults reaching lengths of up to 12 meters (39 feet) and weighing approximately 4 metric tons. These dimensions placed them among the largest herbivorous dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous. Their most distinctive feature was their broad, flattened snout that resembled a duck’s bill, which housed hundreds of teeth arranged in dental batteries—sophisticated structures that allowed for efficient grinding of plant material. Edmontosaurus walked primarily on its hind legs (bipedally) but could drop to all fours (quadrupedally) when feeding or moving slowly. Their front limbs were shorter than their powerful hind limbs, and their hands had hoof-like adaptations rather than claws. Their tails were long and stiffened by ossified tendons, providing balance and potentially serving as defensive weapons against predators.

The Remarkable Dental Battery

Perhaps the most impressive anatomical feature of Edmontosaurus was its sophisticated dental apparatus, which represents one of the most complex tooth arrangements in dinosaur evolution. Unlike most reptiles that simply replace individual teeth, hadrosaurs like Edmontosaurus possessed dental batteries consisting of hundreds of teeth stacked in columns of up to 60 teeth per jaw position. As the exposed teeth wore down through constant grinding of abrasive plant material, they were continuously replaced by new teeth pushing up from below. This conveyor-belt system ensured that Edmontosaurus maintained efficient grinding surfaces throughout its lifetime. Each tooth column functioned as a single grinding unit, creating a continuous surface that could process even tough, fibrous vegetation. This remarkable dental adaptation was key to the success of hadrosaurs, allowing them to exploit plant resources that were unavailable to other herbivorous dinosaurs.

Skin and External Appearance

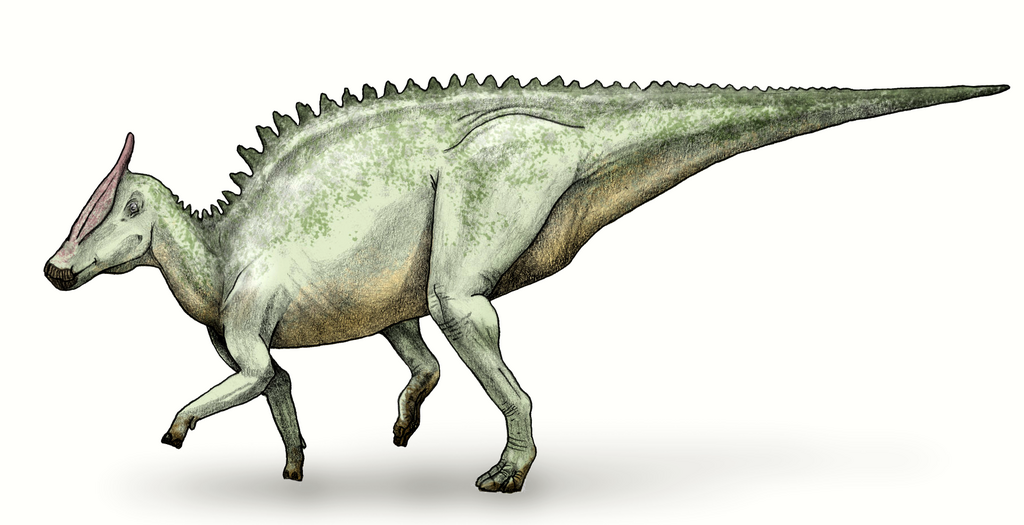

Unlike many dinosaurs known only from skeletal remains, Edmontosaurus has left behind exceptional “mummy” fossils with preserved skin impressions, providing rare insights into its external appearance. These specimens reveal that Edmontosaurus had pebbly skin covered with small, non-overlapping scales that varied in size across different body regions. The skin lacked feathers or prominent display structures, contrary to some other dinosaur groups. One particularly noteworthy discovery was the presence of a soft-tissue crest or wattle along the back of the head in at least some specimens, suggesting that Edmontosaurus may have had more elaborate soft-tissue structures than previously thought. The skin impressions also show that Edmontosaurus had a more robust and muscular build than early skeletal reconstructions suggested, with thick, powerful neck muscles and substantial thighs. The coloration remains speculative, though many scientists propose earthy tones that would have provided camouflage in their woodland and coastal plain environments.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Edmontosaurus fossils have been discovered across a vast geographic range, stretching from Alaska to Colorado and from Alberta to South Dakota. This extensive distribution makes it one of the most widespread dinosaur genera known from the Late Cretaceous period. Paleoenvironmental evidence suggests that Edmontosaurus inhabited coastal lowlands and river floodplains along the western edge of the Western Interior Seaway, a vast inland sea that divided North America into eastern and western landmasses during the Cretaceous period. These environments were characterized by subtropical to warm temperate climates with seasonal variations in rainfall. The vegetation would have included diverse angiosperms (flowering plants), conifers, cycads, and ferns—providing abundant food resources for these large herbivores. Fossil evidence indicates that Edmontosaurus could thrive in a variety of habitats, from coastal swamps to inland forests, demonstrating impressive ecological adaptability that likely contributed to its evolutionary success.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

As a hadrosaur, Edmontosaurus was exclusively herbivorous, with specialized adaptations for processing plant material. Microwear patterns on fossilized teeth suggest that these dinosaurs were primarily ground-level grazers, feeding on tough vegetation including horsetails, ferns, and flowering plants. Their broad, duck-like bills were perfect for cropping vegetation close to the ground, while their powerful dental batteries efficiently ground even fibrous plant materials. Edmontosaurus likely fed by using its flexible bill to gather vegetation before passing it to the dental batteries for processing. Studies of fossilized stomach contents and coprolites (fossilized feces) have revealed that these dinosaurs consumed a diverse plant diet, potentially including conifers, cycads, and early angiosperms. Their ability to process tough, fibrous vegetation that other herbivores couldn’t digest gave them access to abundant food resources and likely contributed to their widespread success across Late Cretaceous North America.

Social Behavior and Herding

Multiple bonebeds containing numerous Edmontosaurus individuals provide compelling evidence that these dinosaurs lived in large herds, perhaps numbering in the hundreds or thousands. This social behavior likely provided protection against predators like Tyrannosaurus rex, which is known to have preyed upon Edmontosaurus based on bite marks found on some specimens. Age distribution within these bonebeds suggests that herds included individuals of various life stages, from juveniles to adults, indicating family groups traveled together. Some paleontologists propose that Edmontosaurus undertook seasonal migrations, moving between feeding grounds as vegetation patterns shifted with the seasons. Their extensive geographic range supports this possibility, as does evidence of different wear patterns on teeth from different locations. Social structures within herds may have been complex, potentially including dominance hierarchies and cooperative behaviors, though direct evidence for specific social dynamics remains elusive.

Reproduction and Growth

The reproductive biology of Edmontosaurus has been pieced together through careful analysis of growth series and comparative studies with related hadrosaurs. Like other dinosaurs, Edmontosaurus laid eggs, though nests specifically attributable to this genus remain rare. Related hadrosaurs are known to have laid clutches of 20-25 eggs in shallow depressions, and Edmontosaurus likely followed a similar pattern. Growth ring studies in Edmontosaurus bones indicate rapid growth during early years, reaching nearly adult size within a decade. However, sexual maturity likely preceded full skeletal maturity, as seen in many modern reptiles and birds. Juvenile Edmontosaurus would have been vulnerable to predation, explaining their inclusion in protective herds. Growth curves suggest that Edmontosaurus experienced different growth phases, with an initial rapid growth period followed by slower growth as the animal approached adult size, a pattern consistent with many large-bodied dinosaurs.

Predators and Defense Mechanisms

Despite their impressive size, Edmontosaurus faced predation from contemporary theropods, most notably Tyrannosaurus rex. Direct evidence of this predator-prey relationship comes from healed bite marks on Edmontosaurus bones and even a fossilized Edmontosaurus tail vertebra with a T. rex tooth embedded in it. To counter such threats, Edmontosaurus relied primarily on safety in numbers, with herd behavior providing vigilance and confusing predators during attacks. Their substantial size would have deterred many predators, as adult Edmontosaurus were too large for most carnivores to tackle alone. When threatened, these dinosaurs could flee using bipedal locomotion, potentially reaching speeds of 25-30 mph in short bursts based on trackway evidence. Their powerful tails could deliver forceful blows, and their sturdy build would have made them formidable opponents even for large predators. Juveniles, being more vulnerable, likely remained protected within the center of herds, surrounded by larger adults.

Paleobiological Insights from “Mummy” Specimens

Exceptionally preserved “mummy” specimens of Edmontosaurus, where skin and other soft tissues were fossilized alongside bones, have provided unprecedented insights into the biology of these dinosaurs. The most famous of these, known as “Dakota,” discovered in North Dakota in 1999, preserved not only skin impressions but also muscle tissue and potentially other internal structures. Studies of these specimens have revealed that Edmontosaurus had more muscular limbs than previously thought, suggesting greater athletic capability than early reconstructions indicated. The preservation of skin from different body regions shows regional variation in scale patterns and thickness, with reinforced skin over areas subject to wear or pressure. Some specimens even show evidence of predation or scavenging, with tooth marks matching those of contemporary predators. These remarkable fossils continue to yield new information as advanced scanning and chemical analysis techniques develop, making Edmontosaurus one of the most completely understood dinosaurs in terms of both skeletal and soft-tissue anatomy.

Extinction at the K-Pg Boundary

Edmontosaurus has the distinction of being among the last non-avian dinosaurs to exist before the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event approximately 66 million years ago. Fossils of Edmontosaurus have been found in the Hell Creek Formation and equivalent deposits, often within meters of the iridium-rich clay layer that marks the impact event believed to have triggered the mass extinction. The abundance of Edmontosaurus in these terminal Cretaceous formations indicates that these dinosaurs were thriving right up until the sudden extinction event. Unlike some dinosaur groups that show evidence of declining diversity before the K-Pg boundary, hadrosaurs like Edmontosaurus remained diverse and widespread, making their abrupt disappearance all the more striking. This pattern suggests that environmental deterioration following the Chicxulub impact, rather than pre-existing ecological stress, was responsible for their extinction. Had the asteroid impact not occurred, Edmontosaurus and its relatives might have continued their evolutionary success into the Cenozoic Era.

Historical Reconstructions and Popular Culture

Edmontosaurus has undergone significant changes in its portrayal over the decades, reflecting evolving scientific understanding of dinosaur biology. Early reconstructions from the early 20th century depicted Edmontosaurus as a slow, tail-dragging swamp-dweller, often shown partially submerged in water. The “Dinosaur Renaissance” of the 1960s and 1970s transformed this image, repositioning Edmontosaurus as an active, terrestrial herbivore with horizontal posture and elevated tail. Modern reconstructions incorporate evidence from skin impressions and biomechanical studies, showing a more muscular animal capable of both bipedal and quadrupedal locomotion. In popular culture, Edmontosaurus has appeared in numerous documentaries, including BBC’s “Walking with Dinosaurs,” and features in museum displays worldwide. Though less iconic than Tyrannosaurus or Triceratops, it remains a staple in discussions of Late Cretaceous ecosystems and features prominently in educational programs about dinosaur social behavior and herbivory.

Ongoing Research and Recent Discoveries

Research on Edmontosaurus continues to yield new insights into dinosaur biology and evolution. Recent histological studies of bone microstructure have refined our understanding of Edmontosaurus growth rates and life history, suggesting these animals reached skeletal maturity at approximately 20 years of age. Advanced CT scanning of skull specimens has revealed previously unrecognized details of the nasal passages and brain cavity, providing clues about sensory capabilities and thermoregulation. Biomechanical modeling has improved our understanding of Edmontosaurus locomotion, suggesting these animals were more agile than previously thought. Geochemical analyses of tooth enamel are shedding light on seasonal dietary variations and potential migration patterns. Perhaps most excitingly, a 2013 study identified evidence of a soft-tissue crest in Edmontosaurus regalis, challenging the long-held view that this species lacked cranial ornamentation. This discovery highlights how even well-studied dinosaurs can still surprise paleontologists and underscores the importance of continuing research on these fascinating creatures.

Conclusion

Edmontosaurus stands as one of paleontology’s most illuminating windows into the world of dinosaurs. These remarkable herbivores, with their sophisticated dental adaptations, complex social behaviors, and widespread ecological success, dominated the Late Cretaceous landscapes of North America until the very end of the dinosaur era. Their abundant fossils, including rare “mummy” specimens with preserved soft tissues, continue to provide valuable insights into dinosaur biology. As research techniques advance, from microscopic analysis of bone structure to sophisticated computer modeling of biomechanics, our understanding of these fascinating creatures grows ever more detailed and nuanced. Edmontosaurus reminds us that even the most seemingly mundane plant-eaters had extraordinary adaptations and complex lives, playing crucial roles in prehistoric ecosystems and writing an important chapter in Earth’s evolutionary history.