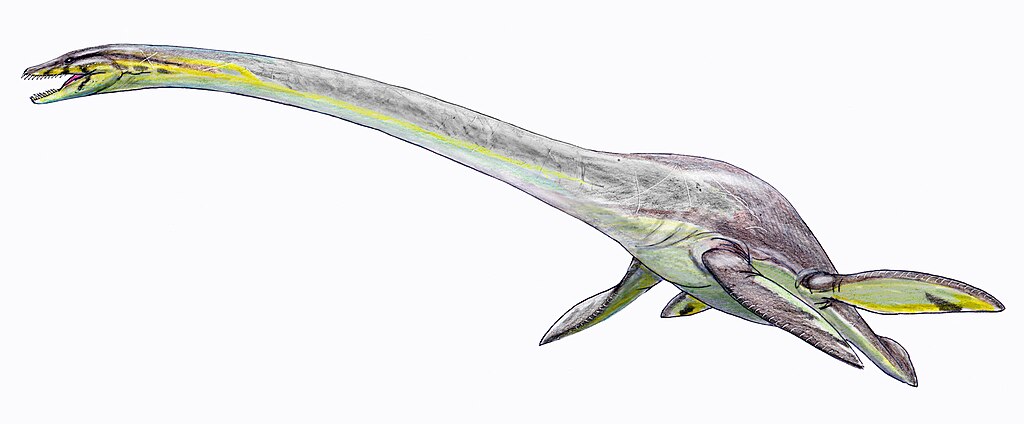

The prehistoric oceans were home to some of Earth’s most remarkable creatures, and few were as strikingly unusual as Elasmosaurus. This extraordinary marine reptile, with its impossibly long neck and streamlined body, swam through the waters of the Late Cretaceous period approximately 80.5 million years ago. As a member of the plesiosaur family, Elasmosaurus has captivated paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike since its discovery in the 1860s. Its distinctive anatomy—particularly that serpentine neck that contained more vertebrae than any other known vertebrate—has made it an icon of ancient marine life and a testament to the diverse evolutionary adaptations that emerged in Earth’s oceans long before humans walked the planet.

Discovery and Naming

Elasmosaurus was first discovered in 1867 by Dr. Theophilus Turner, a military surgeon stationed at Fort Wallace in western Kansas. The fossil remains were found in the Pierre Shale formation, which was once submerged beneath the Western Interior Seaway that divided North America during the Cretaceous period. Turner sent the specimens to paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, one of the prominent scientists involved in the infamous “Bone Wars” of early American paleontology. Cope named the creature Elasmosaurus platyurus in 1868, deriving the name from Greek words “elasmos” meaning “thin plate” and “saurus” meaning “lizard,” referencing the thin plate-like bones that formed parts of its skeleton. The initial reconstruction of Elasmosaurus by Cope became notoriously famous for an embarrassing scientific error—he placed the skull on the end of the tail rather than the neck, a mistake his rival Othniel Charles Marsh later pointed out to Cope’s great embarrassment.

Classification and Evolutionary History

Elasmosaurus belongs to the order Plesiosauria, specifically to the family Elasmosauridae, which is characterized by exceptionally long necks even among plesiosaurs. These marine reptiles were not dinosaurs but rather a separate lineage of reptiles that returned to the sea, similar to how whales evolved from land mammals millions of years later. Plesiosaurs first appeared in the Late Triassic period, approximately 220 million years ago, and diversified throughout the Jurassic period. The elasmosaurids, with their extreme neck elongation, represent a specialized evolutionary branch that reached its peak during the Late Cretaceous period. Fossil evidence suggests that the plesiosaur lineage, including Elasmosaurus, went extinct during the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event approximately 66 million years ago, the same catastrophic event that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs and many other forms of life on Earth.

Anatomical Marvel: The Extraordinary Neck

The most defining feature of Elasmosaurus was undoubtedly its astonishingly long neck, which contained between 70-76 vertebrae—the highest number of neck vertebrae in any known vertebrate animal, living or extinct. This remarkable adaptation accounted for more than half of the creature’s total body length, which could reach up to 14 meters (46 feet). Despite its length, the neck was not particularly flexible when compared to modern-day animals like swans; each individual vertebra had limited mobility, though the cumulative effect allowed for sweeping movements. The vertebrae themselves were relatively short and wide, providing structural support while minimizing weight. Research suggests that the neck couldn’t be held high above the water in a swan-like fashion as often depicted in older illustrations; biomechanical studies indicate that Elasmosaurus likely kept its neck straightened out horizontally while swimming, perhaps occasionally arching it downward to capture prey from the water below.

Body Structure and Size

Beyond its spectacular neck, Elasmosaurus possessed a body perfectly adapted for marine life. Its total length reached approximately 14 meters (46 feet), with the body proper being relatively compact compared to the neck and tail. The creature had a broad, flattened torso reinforced by robust shoulder and hip girdles that anchored its four powerful flipper-like limbs. These flippers, evolved from what were once legs in ancestral land-dwelling reptiles, featured elongated bones arranged in a paddle-like structure ideal for generating thrust through water. Unlike many marine animals that use lateral tail movements for propulsion, Elasmosaurus primarily used its flippers to “fly” through the water, similar to how modern sea turtles and penguins swim. The tail, while substantial, was relatively short compared to the neck and served primarily for stability and directional control rather than propulsion. Weight estimates for adult specimens range between 2 to 4 tons, making them substantial predators in their marine ecosystem.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Elasmosaurus inhabited the warm, shallow seas that covered much of North America during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 80.5 million years ago. Specifically, many of the best-preserved fossils have been discovered in what was once the Western Interior Seaway, an inland sea that divided North America into two landmasses stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean. This ancient marine environment was relatively shallow compared to modern oceans, with depths generally ranging from 100 to 600 meters. The warmer global climate of the Cretaceous period created ideal conditions for a diverse marine ecosystem within these waters. Fossil discoveries indicate that Elasmosaurus was widespread throughout this seaway, with specimens found from present-day Kansas, South Dakota, Colorado, and Texas in the United States, as well as from Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada, suggesting these marine reptiles had a considerable range across the North American marine environment of their time.

Feeding Behavior and Diet

The unusual anatomy of Elasmosaurus has prompted considerable scientific debate regarding its feeding strategies and dietary preferences. With small, needle-like teeth suited for grasping rather than tearing or crushing, Elasmosaurus was clearly not equipped to tackle large prey or hard-shelled organisms. Instead, paleontologists believe these creatures primarily fed on small, fast-moving fish, squid, and possibly crustaceans that they could snare with quick strikes of their extensive necks. Some theories suggest that Elasmosaurus might have hunted by hovering motionless in the water column, using its long neck as a stealth tool to approach prey with minimal body movement, then striking rapidly from an unexpected distance. Stomach contents preserved in some plesiosaur fossils have revealed fish scales, belemnite hooks (from squid-like animals), and occasionally small stones that may have functioned as gastroliths to aid digestion or for ballast. Recent research also suggests that some elasmosaurids may have fed by sifting through bottom sediments with their long necks, hunting for burrowing organisms or benthic creatures hidden in the seafloor.

Swimming Mechanics and Locomotion

The swimming method employed by Elasmosaurus represented a unique adaptation in marine locomotion that differs significantly from most aquatic vertebrates. Rather than using lateral undulations of the body and tail like fish or mosasaurs, Elasmosaurus primarily propelled itself using its four large, wing-like flippers in a movement pattern somewhat analogous to the “underwater flight” of penguins and sea turtles. Computer modeling and studies of the shoulder and hip anatomy suggest that Elasmosaurus used powerful up-and-down strokes with its front flippers, while the hind flippers provided additional thrust and steering capability. This distinctive four-flipper propulsion system would have made Elasmosaurus remarkably maneuverable, capable of precise movements despite its large size. The body remained relatively rigid during swimming, with the flippers generating most of the propulsive force. This locomotion strategy was energetically efficient for steady cruising but may have limited top speed compared to some other marine predators of the time, suggesting Elasmosaurus relied more on endurance and stealth than raw speed when hunting.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Our understanding of how Elasmosaurus reproduced comes largely from broader studies of plesiosaur fossils and comparisons with other marine reptiles. Unlike dinosaurs, which laid eggs on land, plesiosaurs gave birth to live young in the water—a logical necessity for creatures so completely adapted to marine life that they could no longer come ashore. This reproductive strategy, known as viviparity, is evidenced by fossils of pregnant plesiosaurs discovered with embryos preserved inside their body cavities. Studies suggest that plesiosaurs, including Elasmosaurus, likely gave birth to single, well-developed offspring rather than large litters, representing a significant parental investment in each young. Some paleontologists speculate that elasmosaurids may have provided extended parental care to their young, similar to modern whales and dolphins. Growth ring analysis of fossilized bones indicates that Elasmosaurus likely reached sexual maturity after about a decade of growth and could potentially live for several decades, with some estimates suggesting lifespans of 40 years or more for the largest individuals.

Predators and Ecological Relationships

Despite its impressive size, Elasmosaurus was not the apex predator of its marine ecosystem. These long-necked plesiosaurs shared their environment with several formidable predators, including mosasaurs—large marine lizards that could reach sizes comparable to modern killer whales—and massive prehistoric sharks like Cretoxyrhina, aptly nicknamed the “Ginsu shark” for its razor-sharp teeth. Evidence of predation on plesiosaurs comes from fossil specimens bearing distinctive bite marks matching these larger predators, as well as discoveries of shed shark teeth embedded in plesiosaur bones that healed before death, indicating survived attacks. Elasmosaurus likely occupied a middle-tier predator niche, feeding on smaller marine creatures while occasionally falling prey to the larger apex predators. This ecological positioning created complex food web interactions within the Late Cretaceous marine ecosystem. Additionally, Elasmosaurus coexisted with other plesiosaur species, including the shorter-necked, larger-headed polycotylid plesiosaurs, suggesting niche partitioning among these related marine reptiles that allowed multiple species to thrive in the same waters without excessive competitive overlap.

The Controversy of the “Head on the Wrong End”

One of the most infamous episodes in the history of paleontology involves the first scientific description of Elasmosaurus by Edward Drinker Cope in 1868. Working with an incomplete skeleton, Cope mistakenly reconstructed the animal with its skull attached to what was actually the tip of the tail, essentially putting the head on the wrong end of the body. This error occurred partly because no one had ever seen a reptile with such an extraordinarily long neck, leading Cope to assume the longer end must be the tail. His rival paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh later publicly pointed out this embarrassing mistake, reportedly during a lecture Cope was giving. Though Cope attempted to recall published copies of his paper, the error became widely known and damaged his scientific reputation. This incident became a defining moment in the intensely competitive “Bone Wars” between the two scientists, a feud that drove both men to remarkable fossil discoveries but also to scientific mistakes made in haste. Despite this infamous error, Cope’s work on Elasmosaurus still provided the foundation for understanding this remarkable marine reptile, demonstrating how scientific knowledge advances through both discovery and correction.

Comparison to Other Marine Reptiles

The Late Cretaceous seas hosted a diverse array of marine reptiles, each with distinctive adaptations that allowed them to exploit different ecological niches. Compared to its contemporaries, Elasmosaurus stands out primarily for its extreme neck elongation, which far exceeded that of any other marine vertebrate. Mosasaurs, the dominant marine predators of the time, evolved from monitor lizards and featured crocodile-like bodies with powerful tails for propulsion and large jaws lined with conical teeth—a striking contrast to the small-headed, long-necked body plan of Elasmosaurus. Ichthyosaurs, which somewhat resembled dolphins in body shape, had largely declined by the Late Cretaceous but represented yet another distinct marine reptile adaptation with their fish-like bodies, large eyes, and vertical tail flukes. Sea turtles were also present, having already evolved their distinctive shell protection. Even among other plesiosaurs, Elasmosaurus was exceptional—short-necked plesiosaurs like Liopleurodon and Kronosaurus had massive heads with powerful jaws for tackling large prey, representing the opposite evolutionary strategy to the small-headed, long-necked specialization of elasmosaurids. This diversity of marine reptiles demonstrates the evolutionary radiation that occurred as different lineages adapted to various predatory strategies in the ancient oceans.

Cultural Impact and Representation

Since its discovery, Elasmosaurus has captured the public imagination and influenced popular culture’s perception of prehistoric marine life. Its distinctive silhouette, with that improbably long neck, has made it one of the most recognizable prehistoric creatures outside of dinosaurs. The image of Elasmosaurus has featured prominently in museums worldwide, where full skeletal mounts or life-sized models often serve as centerpiece displays in marine fossil exhibitions. In popular media, Elasmosaurus has appeared in numerous documentaries, including BBC’s “Sea Monsters” and various programs on prehistoric life. The creature has also influenced cryptozoology, with some speculating that the legendary Loch Ness Monster might be a surviving plesiosaur—a scientifically impossible notion given the 66-million-year gap since their extinction, but one that speaks to the lasting impression these remarkable animals have made on human imagination. In children’s books and educational materials about prehistoric life, Elasmosaurus frequently appears as an ambassador for ancient marine ecosystems, helping young learners understand the diversity of life that once inhabited Earth’s oceans long before humans evolved.

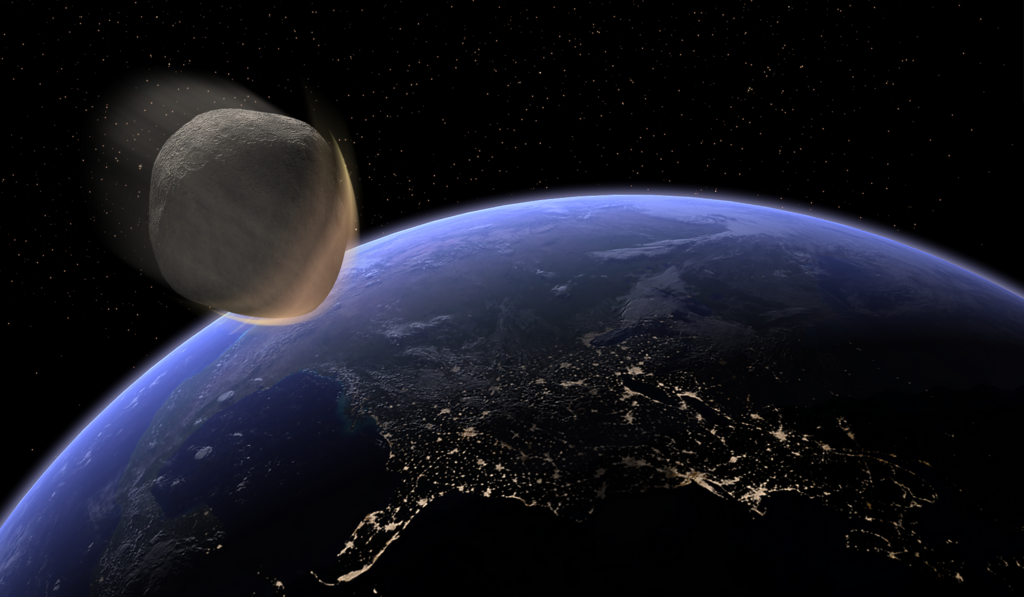

Extinction and Legacy

The reign of Elasmosaurus and its plesiosaur relatives came to an abrupt end approximately 66 million years ago during the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event, the same global catastrophe that eliminated the non-avian dinosaurs. This mass extinction, likely triggered by an asteroid impact in what is now the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, dramatically altered Earth’s climate and ecosystems. The resulting environmental changes, including potential ocean acidification, disruption of marine food chains, and cooling temperatures, proved insurmountable for many marine species, including all plesiosaurs. Despite their successful 135-million-year evolutionary history, these specialized marine reptiles left no direct descendants. However, the ecological niches once occupied by creatures like Elasmosaurus didn’t remain empty for long; in the recovery period following the mass extinction, marine mammals began their own evolutionary journey back to the sea, eventually producing whales, dolphins, and other cetaceans that would become the dominant large marine vertebrates of the modern era. Today, the scientific legacy of Elasmosaurus lives on through continued paleontological research that uses modern technologies like CT scanning and computer modeling to better understand the biomechanics, physiology, and lifestyle of these remarkable marine reptiles, providing valuable insights into the evolutionary processes that shape life on Earth.

Conclusion

Elasmosaurus represents one of nature’s most remarkable evolutionary experiments—a reptile so specialized for marine life that its anatomy challenges our imagination even today. With its extraordinary neck containing more vertebrae than any known animal and its unique four-flipper swimming style, Elasmosaurus exemplifies the diverse adaptations that evolved in marine reptiles during the Mesozoic Era. Although these spectacular creatures vanished during the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period, their fossils continue to provide valuable insights into ancient marine ecosystems and the evolutionary processes that shape life on Earth. As we continue to discover and study their remains, our understanding of these long-necked wonders grows, allowing us to piece together the fascinating story of life in Earth’s prehistoric oceans. Elasmosaurus may have disappeared from our planet’s waters 66 million years ago, but in the annals of evolutionary history and in our collective fascination with prehistoric life, these remarkable marine reptiles continue to make waves.