The discovery of dinosaur fossils in the early 19th century sparked a revolution not just in science but in the public imagination. As paleontologists unearthed these prehistoric giants, society encountered creatures unlike anything in living memory—beasts that challenged biblical timelines and evolutionary understanding. The journey from initial scientific puzzlement to worldwide dinosaur mania represents one of history’s most fascinating intersections of scientific discovery and popular culture. This transformation from obscure fossils to cultural icons illuminates how scientific breakthroughs can capture public fascination, reshaping our understanding of Earth’s history while simultaneously influencing art, literature, and entertainment for generations to come.

The First Discoveries: Puzzling Bones and Initial Confusion

Long before the word “dinosaur” existed, large fossil bones occasionally surfaced throughout human history, often misinterpreted as the remains of biblical giants or mythological creatures. The first scientifically documented dinosaur remains emerged in early 19th century England, when unusual teeth and bones caught the attention of natural scientists. In 1822, Mary Ann Mantell, wife of physician and geologist Gideon Mantell, reportedly spotted unusual teeth while accompanying her husband on a country walk, leading to the eventual identification of Iguanodon. Meanwhile, quarry workers in Oxfordshire had unearthed massive bones that would later be named Megalosaurus, studied by William Buckland and described formally in 1824. These initial findings created considerable confusion, as scientists struggled to place these enormous creatures within the known natural order, initially suggesting they might be extraordinarily large lizards or perhaps evidence of antediluvian monsters mentioned in scripture.

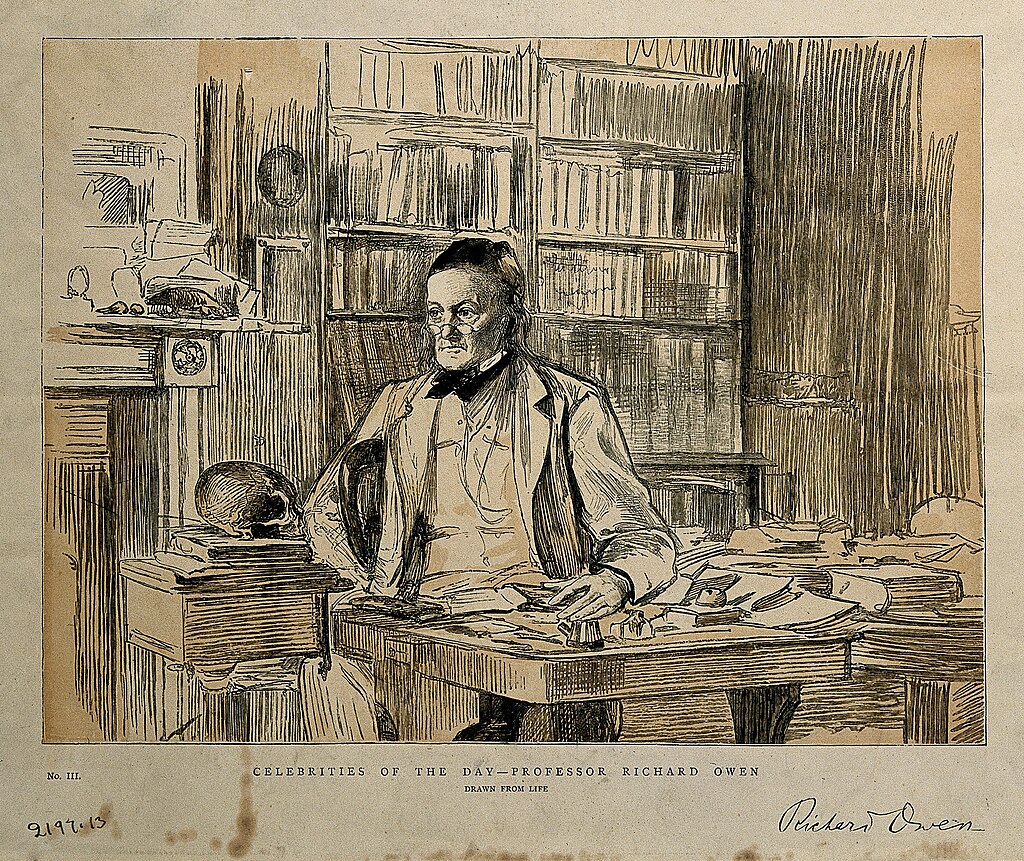

Sir Richard Owen and the Birth of “Dinosauria”

The scattered puzzle pieces of prehistoric reptile discoveries gained coherence in 1842 when anatomist Sir Richard Owen coined the term “Dinosauria,” meaning “terrible lizards,” to unite these creatures as a distinct taxonomic group. Owen’s recognition that Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus shared specific anatomical features represented a watershed moment in paleontology, establishing dinosaurs as a unique group of animals unlike modern reptiles. By identifying distinctive vertebral structures and upright limb positions, Owen determined these were not merely oversized lizards but represented something entirely different—a group of often massive reptiles that had dominated terrestrial ecosystems in the distant past. His presentation to the British Association for the Advancement of Science effectively launched dinosaur paleontology as a scientific discipline and provided the foundation for public understanding of these extinct creatures. Despite later revisions to many of Owen’s conclusions, his conceptual framework of dinosaurs as a unified group of prehistoric animals permanently altered both scientific classification and popular imagination.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: First Public Representations

The most dramatic early convergence of dinosaur science and public spectacle occurred at London’s Crystal Palace Park in the 1850s, where Owen collaborated with sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to create the world’s first life-sized dinosaur models. These massive concrete and brick sculptures—representing Iguanodon, Megalosaurus, and other prehistoric creatures—became an immediate sensation when unveiled in 1854, providing Victorian audiences their first visual encounter with the ancient world. The sculptures reflected Owen’s interpretation of dinosaurs as massive, quadrupedal reptiles, a view later proved incorrect but which shaped early public perceptions. Famously, Hawkins and Owen even hosted a New Year’s Eve dinner party inside an unfinished Iguanodon model in 1853, with scientific luminaries dining within the beast’s ribcage—perhaps the first example of dinosaur-themed entertainment. Though scientifically outdated today, the Crystal Palace dinosaurs remain historically significant as the first attempt to visualize these creatures for public consumption, and they still stand as protected monuments, offering a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of paleontological understanding.

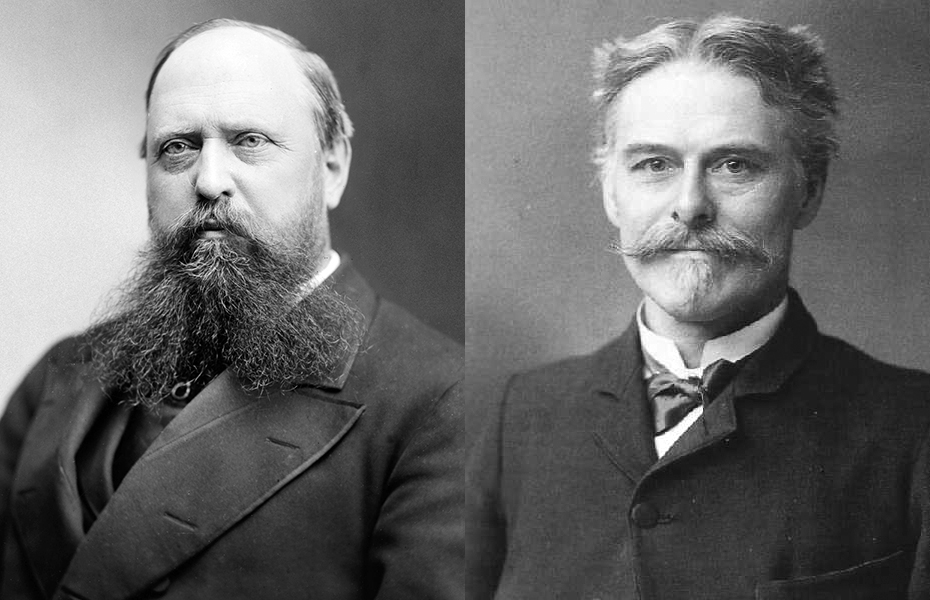

The Bone Wars: Scientific Competition Fuels Public Interest

American dinosaur paleontology exploded into public consciousness during the infamous “Bone Wars” of the late 19th century, a fierce rivalry between paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh that transformed both scientific knowledge and public fascination. Between the 1870s and 1890s, these scientific adversaries engaged in increasingly antagonistic competition, racing to discover, name, and publish findings on new dinosaur species across the American West. Their bitter rivalry—marked by espionage, sabotage, and public attacks in scientific journals—led to hasty fieldwork and scientific shortcuts, yet paradoxically resulted in the discovery of over 130 new dinosaur species, including iconic specimens like Triceratops, Stegosaurus, and Diplodocus. Newspapers eagerly covered this scientific feud, bringing paleontological discoveries directly to the American public through sensationalized accounts that emphasized both the spectacular nature of the fossils and the personal drama between the scientists. The Bone Wars effectively transformed dinosaur discovery from an obscure scientific pursuit into newsworthy material that captured public imagination, establishing dinosaurs as household names and creating the first real dinosaur celebrities among both the scientists and their discoveries.

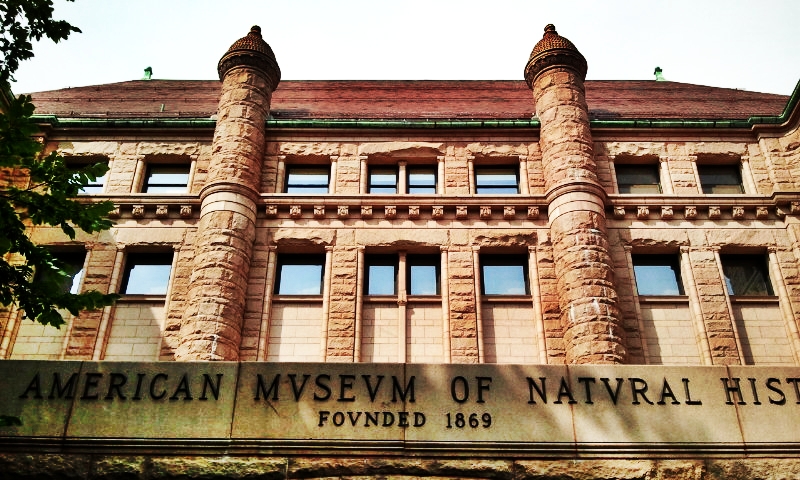

Museum Displays: Bringing Dinosaurs to the Masses

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a revolutionary transformation in natural history museums, as institutions raced to mount complete dinosaur skeletons for public display, forever changing how ordinary people encountered prehistoric life. The American Museum of Natural History in New York, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, and London’s Natural History Museum competed to collect, prepare, and display increasingly spectacular specimens that would draw crowds and establish institutional prestige. The first mounted Diplodocus skeleton, unveiled at the Carnegie Museum in 1907, shocked visitors with its 84-foot length, while the American Museum’s Brontosaurus (now Apatosaurus) became an immediate icon when displayed in 1905. These early exhibitions typically presented dinosaurs as lumbering, tail-dragging behemoths in static poses—scientific interpretations later revised, but which shaped public perception for generations. Museum directors recognized dinosaurs’ unique appeal as attention-grabbing spectacles that could attract visitors while simultaneously educating them about evolutionary history and geological time. The resulting “dinosaur halls” became centerpieces of natural history museums worldwide, establishing these institutions as temples of both scientific knowledge and public entertainment where visitors could stand in the literal shadow of Earth’s lost giants.

Challenging Biblical Timelines: Dinosaurs and Religious Controversy

Dinosaur discoveries introduced profound theological challenges in the 19th century, as these ancient creatures existed nowhere in biblical accounts and required timeframes far exceeding traditional religious chronologies. Many Christian authorities of the era adhered to Bishop James Ussher’s 17th-century calculation placing Earth’s creation at 4004 BCE—a timeline utterly incompatible with creatures that had lived tens of millions of years earlier and disappeared long before human existence. Some religious thinkers attempted reconciliation by suggesting dinosaur fossils were planted by God to test faith, or alternatively, that they represented casualties of Noah’s flood. The growing acceptance of geological deep time forced significant theological reconsideration, with some religious authorities eventually adopting interpretations that separated “creation days” from literal 24-hour periods. Dinosaur fossils thus became central exhibits in the broader Victorian debate between science and religion, contributing to the period’s intense cultural anxiety about traditional belief systems. This theological disruption helps explain why dinosaurs captured such intense public interest—they weren’t merely scientific curiosities but creatures whose very existence challenged fundamental assumptions about creation, biblical authority, and humanity’s place in natural history.

The Shifting Image: From Sluggish Reptiles to Dynamic Creatures

The scientific understanding of dinosaurs has undergone dramatic revisions since their initial discovery, with each major shift in interpretation generating renewed public fascination. Early Victorian paleontologists portrayed dinosaurs as oversized, sluggish reptiles—essentially gigantic lizards with elephantine postures—an interpretation visibly embodied in the Crystal Palace sculptures where Iguanodon appears as a heavy quadruped with a misplaced thumb spike on its nose. This view began changing in the early 20th century, most notably with the discoveries of Roy Chapman Andrews and the Central Asiatic Expeditions, which found dinosaur eggs and nesting sites suggesting more complex behaviors. A revolutionary reassessment occurred in the 1960s when John Ostrom described Deinonychus as an active, warm-blooded predator, launching the “Dinosaur Renaissance” that reimagined many species as agile, dynamic animals closer to birds than reptiles. Each scientific reinterpretation—from the discovery of feathered dinosaurs in China to evidence of complex social behaviors—has triggered waves of public excitement and media coverage. These evolving scientific views have repeatedly refreshed dinosaurs’ cultural appeal, with each generation encountering creatures that seem simultaneously familiar yet newly surprising as paleontological understanding advances.

Literary Dinosaurs: Prehistoric Beasts in Early Fiction

The literary world quickly recognized dinosaurs’ narrative potential, with authors incorporating these prehistoric creatures into fiction beginning in the late 19th century, transforming scientific discoveries into adventure stories that further amplified public fascination. Charles Dickens’ magazine “Household Words” published “Extinct Animals” in 1854, bringing Owen’s paleontological work to a broader reading audience and helping establish dinosaurs in the public lexicon. Jules Verne’s “Journey to the Center of the Earth” (1864) featured prehistoric creatures still surviving in subterranean realms, establishing a template for “lost world” narratives. This approach reached its definitive expression in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Lost World” (1912), where Professor Challenger discovers living dinosaurs on a South American plateau, directly inspiring generations of dinosaur adventure tales. These early fictional treatments reinforced dinosaurs’ cultural status as both scientifically legitimate and imaginatively compelling—creatures with one foot in serious natural history and another in spectacular entertainment. By translating paleontological discoveries into narrative adventures, authors helped cement dinosaurs in popular culture long before film or television existed, expanding their audience beyond those who visited museums or read scientific journals.

Dinosaurs as National Treasures: Patriotic Paleontology

Dinosaur discoveries quickly acquired patriotic dimensions as nations came to view impressive specimens as symbols of national prestige and scientific achievement, particularly during the imperial age. American institutions emphasized the spectacular size of dinosaurs from the Western frontier, with creatures like Brontosaurus and Tyrannosaurus rex becoming unofficial national symbols that represented American natural bounty and scientific prowess. European powers similarly invested in dinosaur collecting as extensions of imperial scientific enterprise, with German expeditions to Tendaguru (in what is now Tanzania) recovering the massive Brachiosaurus, proudly displayed in Berlin until World War II. The British Museum organized collecting expeditions throughout its colonial territories, presenting resulting specimens as testament to Britain’s global scientific leadership. Argentina and other South American nations later embraced their unique dinosaur heritage, with creatures like Giganotosaurus and Argentinosaurus becoming sources of national pride. This nationalistic dimension helped secure government funding for paleontological research and museum construction while simultaneously raising dinosaurs’ profile in public consciousness. By becoming entangled with national identity, dinosaurs transcended purely scientific interest to become cultural patrimony—prehistoric creatures adopted as symbols of modern nations.

Educational Outreach: Dinosaurs as Gateway to Science

Educators and science communicators quickly recognized dinosaurs’ unique ability to capture children’s imagination, making them invaluable tools for introducing younger audiences to broader scientific concepts. Natural history museums developed specialized dinosaur-focused educational programs as early as the 1920s, using these creatures as entry points to discuss evolution, geology, climate change, and extinction events. Children’s books about dinosaurs proliferated in the early 20th century, with works like Roy Chapman Andrews’ popular accounts of his Mongolian expeditions introducing generations of young readers to both paleontology and scientific methodology. The American Museum of Natural History’s dinosaur halls became required destinations for school field trips, exposing millions of children to scientific inquiry through their intrinsic fascination with these prehistoric creatures. This educational utility helped justify continued institutional investment in dinosaur research and exhibitions despite their scientific specialization. Even today, studies consistently show dinosaurs serve as one of the most effective “gateway sciences” for children, often representing their first substantive encounter with scientific concepts and potentially inspiring lifelong scientific interest. This educational dimension has been central to dinosaurs’ enduring cultural prominence, ensuring their continued presence in curriculum, children’s media, and educational programming.

The Commercial Appeal: Early Dinosaur Merchandising

The commercial potential of dinosaurs emerged remarkably early, with entrepreneurs recognizing their marketability as distinctive characters that could sell products, toys, and experiences. Sinclair Oil Corporation adopted the Brontosaurus (now Apatosaurus) as its corporate logo in 1930, claiming that the petroleum in their products originated during the “Age of Dinosaurs”—a scientifically dubious but marketing-savvy connection that made their green dinosaur one of America’s most recognized corporate symbols. Toy dinosaurs appeared in the early 20th century, with manufacturers like Marx producing detailed plastic dinosaur playsets by the 1950s that became staples of childhood play. Publishers capitalized on dinosaur appeal with illustrated books and trading cards, while natural history museums developed gift shops centered around dinosaur merchandise, turning exhibition visitors into customers. The 1933 film “King Kong” featured dinosaurs as spectacular adversaries on Skull Island, demonstrating their cinematic appeal decades before “Jurassic Park.” This commercial dimension established dinosaurs as valuable intellectual property and recognizable characters with built-in audience appeal. The resulting economic incentives encouraged further investment in dinosaur research, museum exhibitions, and media portrayals, creating a positive feedback loop where scientific discovery, public interest, and commercial exploitation mutually reinforced dinosaurs’ cultural prominence.

The Legacy: How Early Dinosaur Reception Shaped Modern Understanding

The patterns established during the first century of dinosaur reception continue to influence both scientific practice and public engagement with paleontology today, creating enduring frameworks for how we understand and interact with prehistoric life. Early sensationalist newspaper coverage of the Bone Wars established templates for media reporting on dinosaur discoveries that persist in contemporary journalism, where new species are still announced with dramatic headlines emphasizing size, ferocity, or superlative characteristics. The museum tradition of mounting complete skeletons as public spectacles remains central to institutional identity and visitor expectations, with technology merely enhancing rather than replacing this fundamental approach to exhibition. Early fictional portrayals of dinosaurs as adventure story elements set narrative patterns still evident in everything from “Jurassic Park” to children’s programming. Even the scientific tensions between specialists and popularizers that characterized early disagreements between Richard Owen and Gideon Mantell continue in modern debates about scientific accuracy versus public accessibility. The early fusion of scientific legitimacy with entertainment value established dinosaurs in a unique cultural position that they retain today—creatures that simultaneously belong to serious scientific inquiry and popular culture, equally at home in peer-reviewed journals and children’s lunch boxes. This dual citizenship between scientific and popular domains explains dinosaurs’ remarkable cultural longevity and continued ability to fascinate successive generations.

Conclusion

The transformation of dinosaurs from obscure scientific specimens to global cultural icons represents one of history’s most successful bridges between specialized scientific knowledge and popular enthusiasm. The early reception of dinosaur discoveries established enduring patterns in how science enters public consciousness, demonstrating that scientific breakthroughs can capture imagination across social classes, educational backgrounds, and national boundaries when they engage with fundamental questions about our world and its history. From the Crystal Palace sculptures to museum halls, from academic debates to children’s toys, dinosaurs traveled a remarkable path from scientific curiosity to cultural ubiquity. This journey illuminates not just paleontological history but the broader relationship between scientific discovery and public engagement—a relationship that continues to evolve as new technologies and media create novel ways for people to encounter Earth’s most famous extinct inhabitants. The enduring fascination with dinosaurs testifies to their unique power as creatures that, despite having vanished millions of years before human existence, somehow feel intimately connected to our understanding of the planet we inhabit.