Deep in the world’s remaining old-growth forests, hidden in crystal-clear mountain streams, and lurking beneath the murky waters of ancient lakes, Earth’s giant amphibians have thrived for millions of years. These remarkable creatures—some reaching lengths of over five feet—represent living connections to prehistoric times when amphibians ruled much of the planet. Today, however, these magnificent animals face unprecedented challenges that threaten their very existence. From the Chinese giant salamander’s precipitous decline to the struggle of massive aquatic frogs in Lake Titicaca, giant amphibians worldwide are disappearing at alarming rates. Their story is one of evolutionary marvel, ecological importance, and urgent conservation need as human activities increasingly encroach upon their shrinking habitats.

The Ancient Lineage of Giant Amphibians

Giant amphibians aren’t just impressive for their size—they represent some of the oldest vertebrate lineages still in existence. Many of today’s largest species evolved from ancestors that roamed Earth during the Jurassic period, making them living fossils in the truest sense. The Japanese giant salamander, for instance, belongs to a family that first appeared approximately 65 million years ago, around the time dinosaurs went extinct. These creatures have survived multiple mass extinction events through remarkable adaptability and specialized traits. Their persistence through time offers scientists unique opportunities to study evolutionary processes and adaptation mechanisms that have allowed them to survive while countless other species disappeared. This ancient heritage makes their current decline all the more tragic from both scientific and ecological perspectives.

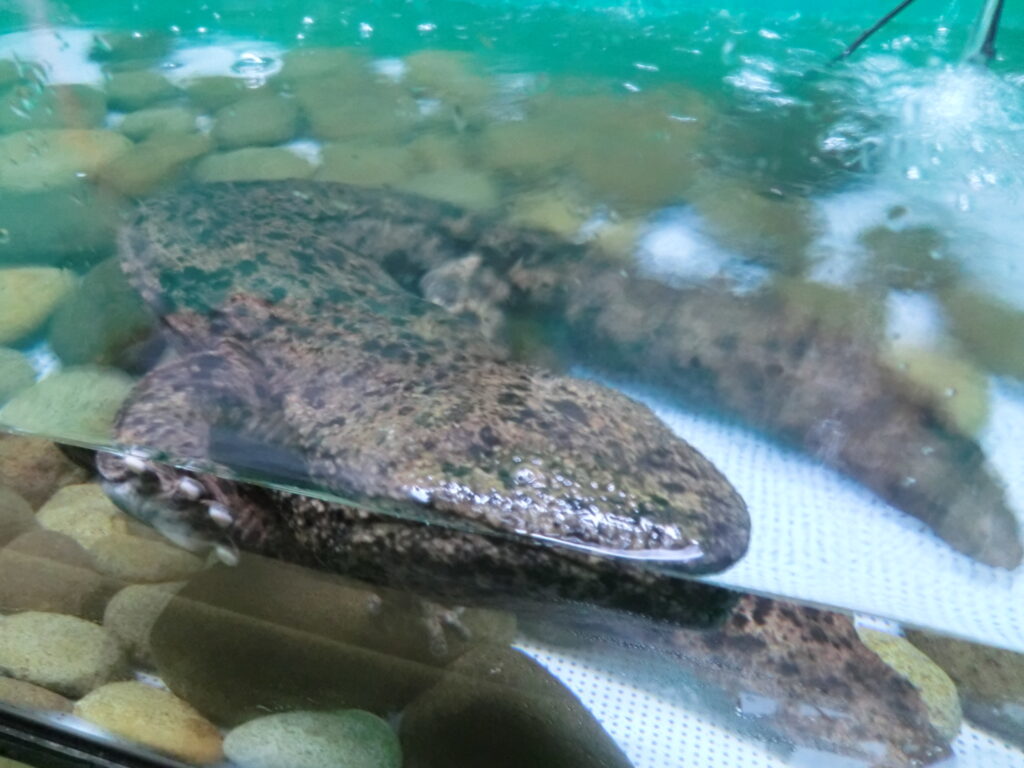

The Chinese Giant Salamander: World’s Largest Amphibian

The Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) stands as the undisputed titan of the amphibian world, capable of growing to an astonishing 6 feet (1.8 meters) in length and weighing up to 140 pounds (64 kilograms). These remarkable creatures possess wrinkled, brownish skin that helps them blend into their riverbed habitats, while their flattened bodies and broad heads are perfectly adapted for ambush hunting in fast-flowing mountain streams. Unlike many amphibians, they can live up to 60 years in the wild, making them among the longest-lived amphibians on Earth. Their unique vocalizations—described as sounding like a baby’s cry—have earned them the nickname “baby fish” in parts of China. Once abundant throughout central and southern China’s mountain streams, wild populations have plummeted by more than 80% since the 1950s, primarily due to overharvesting for luxury food markets and traditional medicine.

The Japanese Giant Salamander: Cultural Icon

The Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus), cousin to the Chinese species, has achieved a status few amphibians can claim—becoming a cultural icon deeply embedded in Japanese folklore and conservation consciousness. Growing to lengths of up to 5 feet (1.5 meters), these massive salamanders populate cold, fast-flowing mountain streams across central and western Japan. Their Japanese name, “Ōsanshōuo,” translates roughly to “giant pepper fish,” referring to the pepper-like scent they emit when threatened. In Japanese mythology, they appear as “river children” or “kappa”—water spirits that can be both mischievous and dangerous. Unlike their Chinese relatives, Japanese giant salamanders enjoy significant legal protection and cultural reverence, with some municipalities establishing special conservation zones and education centers dedicated to their preservation. This cultural integration has helped maintain populations better than in neighboring China, though habitat degradation and damming still pose serious threats to their long-term survival.

North America’s Hellbender: A Giant in Decline

North America hosts its giant amphibian in the form of the hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis), a remarkable salamander that can reach lengths of over two feet. These ancient creatures, sometimes called “snot otters” or “devil dogs” due to their slimy skin and unusual appearance, inhabit cool, oxygen-rich streams throughout the Appalachian region. Hellbenders possess a series of distinctive folds along their sides that increase their surface area, allowing them to absorb oxygen directly through their skin without using their simple lungs. Unlike their Asian relatives, hellbenders are completely aquatic and rarely leave the protection of the large, flat rocks under which they make their homes. Despite being protected in many states, hellbender populations have declined by more than 70% across much of their range due to stream sedimentation, water pollution, and dam construction that alters the fast-flowing, oxygen-rich conditions they require. Conservation efforts now include captive breeding programs and artificial nest boxes to help restore declining populations before they disappear entirely.

Lake Titicaca’s Giant Frog: Adapting to Extreme Environments

High in the Andes Mountains, straddling the border between Peru and Bolivia, Lake Titicaca hosts another remarkable giant amphibian—the Lake Titicaca frog (Telmatobius culeus). These extraordinary frogs can grow to over 20 inches (50 cm) long and weigh up to 2.2 pounds (1 kg), making them among the largest truly aquatic frogs in the world. What truly sets them apart, however, is their highly specialized adaptation to the oxygen-poor waters of Lake Titicaca, which sits at an elevation of 12,500 feet (3,810 meters). Their skin has evolved extensive folds and wrinkles that dramatically increase surface area, earning them the nickname “scrotum frogs” due to their appearance. These skin adaptations allow them to extract enough oxygen from the water that they rarely need to surface for air, even in the cold, thin-air conditions of their high-altitude home. Unfortunately, these unique frogs face catastrophic population declines due to overharvesting for supposed medicinal properties, pollution from mining operations, and the introduction of invasive trout that prey on juvenile frogs.

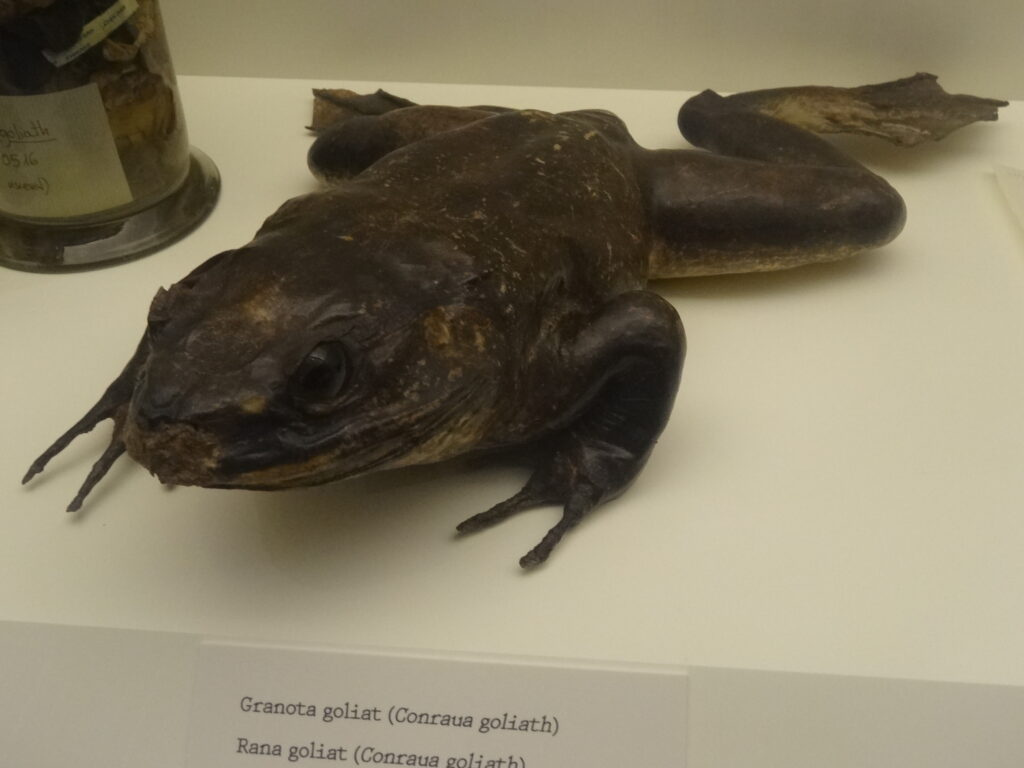

The Goliath Frog: Africa’s Heavyweight Champion

Africa contributes to the roster of giant amphibians with the impressive Goliath frog (Conraua goliath), the world’s largest frog by weight. Native to fast-flowing rivers in Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea, these massive amphibians can reach lengths of over 12 inches (32 cm) and weigh up to 7 pounds (3.3 kg)—roughly the size of a house cat. Unlike many frogs that produce thousands of eggs, female Goliath frogs lay just a few hundred large eggs in carefully constructed rock nests within rapids. What’s particularly remarkable about these giants is their incredible strength and jumping ability; despite their bulk, they can leap nearly 10 feet (3 meters) in a single bound. Recent research has revealed that male Goliath frogs engage in a unique breeding behavior by moving rocks weighing up to their body weight to build protected pools for their offspring. This extraordinary commitment to parental care is rare among amphibians but may explain why they produce relatively few eggs compared to other frog species. Sadly, Goliath frog populations have declined by more than 50% in recent decades due to deforestation, hunting for bushmeat markets, and hydroelectric projects that disrupt their breeding sites.

South American Horned Frogs: Voracious Giants

The South American continent hosts several species of exceptionally large amphibians known as horned frogs or “Pacman frogs” (Ceratophrys species), named for their enormous mouths and voracious appetites. These ground-dwelling ambush predators can grow to 8 inches (20 cm) in length and weigh over 2 pounds (0.9 kg), with females typically larger than males. Their most distinctive feature is the pair of horn-like projections above their eyes, which, combined with their massive jaws, give them a formidable appearance. These frogs possess extraordinarily powerful jaws that can deliver a bite force equivalent to many mammalian predators several times their size. Their aggressive feeding strategy allows them to consume prey up to half their body size, including other frogs, small reptiles, birds, rodents, and even venomous snakes. While not as immediately threatened as some other giant amphibians, several horned frog species face habitat loss in the Amazon basin and other South American ecosystems, while collection for the exotic pet trade has impacted some populations.

The Ecological Importance of Giant Amphibians

Giant amphibians play crucial ecological roles that extend far beyond their impressive size, serving as both predators and prey within their ecosystems. As apex predators in aquatic environments, species like the Chinese giant salamander and hellbender help regulate populations of fish, crayfish, and smaller amphibians, maintaining balanced aquatic communities. Their feeding activities can influence the entire trophic structure of streams and lakes, preventing any single prey species from dominating. Additionally, many giant amphibian species serve as environmental indicators due to their sensitive skin and strict habitat requirements; their presence or absence provides valuable information about water quality and ecosystem health. The decline of these species often signals broader environmental degradation that ultimately affects human water sources as well. Their larvae and eggs also provide important food sources for numerous aquatic predators, creating essential energy pathways between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. This ecological significance makes their conservation not merely about saving individual species but preserving entire ecosystem functions.

Habitat Destruction: The Primary Threat

While giant amphibians face numerous challenges, habitat destruction remains the most pervasive and immediate threat to their survival worldwide. Deforestation in watershed areas leads to increased sedimentation in streams, literally suffocating the clean, rocky stream bottoms that many giant salamanders require for breeding and feeding. Damming projects have fragmented river systems and altered water flow patterns critical for species like the Chinese and Japanese giant salamanders, preventing migration to breeding grounds and isolating populations. Agricultural runoff containing pesticides and fertilizers is particularly devastating to amphibians, whose permeable skin readily absorbs these chemicals, causing developmental abnormalities, reproductive failures, and direct mortality. In Lake Titicaca, urban development and inadequate sewage treatment have introduced unprecedented levels of pollution, creating toxic conditions for the lake’s endemic giant frogs. Mining operations near amphibian habitats release heavy metals and alter pH levels in ways that can be immediately lethal or cause long-term reproductive damage. Without comprehensive habitat protection that addresses these multiple threat vectors, even the most well-intentioned species-specific conservation efforts may ultimately fail to save these remarkable giants.

Climate Change: New Challenges for Ancient Species

Climate change presents a particularly insidious threat to giant amphibians, whose evolutionary adaptations to specific environmental conditions leave them vulnerable to rapid change. Rising global temperatures directly impact cold-adapted species like the hellbender and Japanese giant salamander, whose physiological processes are optimized for cool, highly oxygenated water. Even small temperature increases can reduce dissolved oxygen levels below their minimum requirements, especially during critical reproductive periods. Altered precipitation patterns lead to more extreme flooding and drought cycles, washing away egg masses during floods or leaving breeding pools completely dry before metamorphosis can occur. For high-altitude specialists like the Lake Titicaca frog, warming temperatures allow the upward migration of predatory species and pathogens previously limited to lower elevations. Climate projections suggest that suitable habitat for many giant amphibian species could contract by 30-70% within the next several decades as temperature and precipitation patterns shift faster than these long-lived, slow-reproducing species can adapt. Their limited dispersal abilities further complicate matters, as many cannot simply migrate to more suitable habitats when their current ranges become inhospitable.

Overharvesting: From Traditional Medicine to Gourmet Tables

Human exploitation represents a direct and severe threat to several giant amphibian species, particularly in Asia, where these animals have long been valued in traditional medicine and cuisine. The Chinese giant salamander has been particularly devastated by commercial harvesting, with wild individuals commanding prices exceeding $1,000 per kilogram in specialty restaurants, where they’re considered a luxury delicacy and status symbol. Traditional medicinal practices attribute various healing properties to giant salamander parts, including treatments for respiratory ailments and sexual enhancement, despite no scientific evidence supporting these claims. In Peru and Bolivia, Lake Titicaca frogs are harvested and blended into “frog juice,” sold as a treatment for respiratory problems and as an aphrodisiac. The Goliath frog faces similar pressures in Central Africa, where it’s hunted for bushmeat markets and local consumption. While some countries have implemented legal protections for these species, enforcement remains challenging in remote areas, and black market demand continues to drive poaching. Conservation efforts increasingly focus on developing sustainable captive breeding programs that might satisfy commercial demand while allowing wild populations to recover, though the effectiveness of this approach remains controversial among conservationists.

Disease and Invasive Species: Modern Threats

Beyond habitat destruction and direct harvesting, giant amphibians face relatively new threats from emerging diseases and invasive species that their populations have little evolutionary experience confronting. The devastating chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), which has contributed to the decline or extinction of over 200 amphibian species worldwide, poses a serious threat to many giant amphibians. While some species show varying degrees of resistance, the fungus continues to spread into new areas, potentially affecting previously unexposed populations. Invasive species present another significant challenge, as introduced predatory fish like rainbow trout consume the eggs and larvae of giant amphibians, while competing species may displace natives from their ecological niches. In North America, for example, introduced crayfish species not only compete with hellbenders for food but also prey directly on their eggs and juveniles. The Lake Titicaca frog faces similar pressures from introduced trout that have devastated juvenile populations. Additionally, pollution-tolerant invasive bullfrogs often thrive in degraded habitats where native giant amphibians struggle, creating a compounding effect that accelerates the decline of these specialized giants while generalist invaders flourish in human-altered landscapes.

Conservation Efforts and Success Stories

Despite the numerous challenges facing giant amphibians, dedicated conservation efforts have begun to yield promising results in several regions. In Japan, extensive legal protections combined with public education campaigns have helped stabilize some populations of the Japanese giant salamander, with special protected areas established in key watersheds. North American hellbender conservation has made significant strides through artificial nest box programs, where concrete structures mimicking natural breeding sites have increased reproductive success in degraded habitats. The Cincinnati Zoo’s successful hellbender breeding program has released thousands of captive-reared juveniles into the wild, boosting populations in Ohio and Kentucky. For the Chinese giant salamander, strict enforcement of anti-poaching laws in certain provinces has reduced illegal harvesting, while state-sponsored conservation breeding facilities work to maintain genetic diversity for potential reintroduction programs. Several conservation organizations have established “amphibian arks”—specialized breeding facilities that maintain assurance populations of the most threatened species until wild habitat conditions improve. While these efforts represent important steps forward, conservationists emphasize that without addressing the underlying threats of habitat degradation and climate change, such interventions may only delay, rather than prevent, the extinction of these remarkable species.

The Future of Giant Amphibians: What Can Be Done?

Securing a future for the world’s giant amphibians will require coordinated action across multiple fronts, from local conservation initiatives to global policy changes. Expanding protected area networks specifically designed to safeguard watersheds where these species occur represents a crucial first step, particularly when these protections extend across entire river systems rather than isolated fragments. Strengthening and enforcing laws against poaching and illegal wildlife trade, especially in Asia where consumption pressures are highest, must be coupled with community education programs that build cultural value for living amphibians rather than consumed ones. Restoration of degraded habitats, particularly through riparian reforestation and stream channel rehabilitation, can recreate suitable conditions in areas where populations have been lost. Climate change mitigation efforts take on special urgency for these cold-adapted species, as many simply cannot survive in warming waters, regardless of other conservation measures. Perhaps most importantly, conservation strategies must engage local communities as partners through initiatives that provide sustainable livelihoods connected to amphibian conservation, whether through ecotourism, watershed protection jobs, or sustainable agriculture practices that reduce stream pollution. With their ancient lineages and remarkable adaptations, giant amphibians represent irreplaceable components of Earth’s biodiversity—living links to prehistoric ecosystems that, once lost, can never be recovered.

Evolutionary Marvels on the Brink of Disappearance

From the misty mountain streams of East Asia to the cold depths of Lake Titicaca, giant amphibians stand as remarkable examples of evolutionary specialization and ecological adaptation. Their outsized bodies house equally impressive biological innovations that have allowed them to thrive for millions of years—until now. As human activities increasingly