In the shadowy waters of prehistoric rivers and coastal regions, enormous crocodilian predators lurked, some growing large enough to prey upon dinosaurs that ventured too close to the water’s edge. These ancient reptiles were not the crocodiles we recognize today but were their distant relatives, often larger and more terrifying. Some of these massive predators shared ecosystems with dinosaurs for millions of years, evolving specialized adaptations that allowed them to become apex predators in their own right. This article explores the fascinating world of giant prehistoric crocodilians, their relationships with dinosaurs, and the evidence that reveals their hunting behaviors.

Origins of Giant Crocodilians

The crocodilian lineage extends back over 200 million years, evolving alongside dinosaurs during the Mesozoic Era. While modern crocodiles and alligators belong to the group Crocodylia, the giant prehistoric forms included members of several related lineages, collectively known as Crocodyliformes. These ancient crocodile relatives diverged from their common ancestor with dinosaurs during the Triassic period, around 250 million years ago. Through natural selection, certain crocodyliform lineages evolved massive body sizes, powerful jaws, and hunting strategies that allowed them to prey on large animals, including some dinosaurs. The fossil record indicates that these giants were particularly prevalent during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 100 to 66 million years ago, when some species reached truly monstrous proportions and became dominant predators in many aquatic ecosystems.

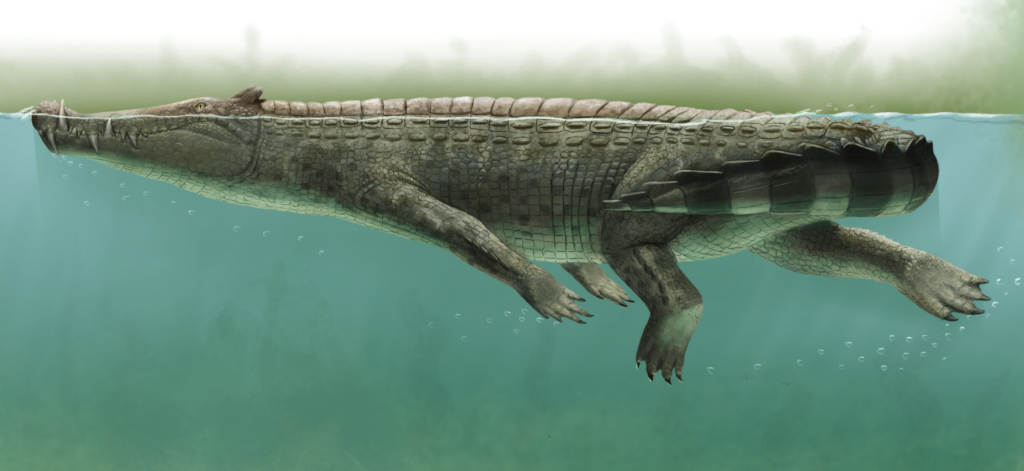

Sarcosuchus: The “Flesh Crocodile”

Perhaps the most famous of these prehistoric giants was Sarcosuchus imperator, aptly nicknamed the “flesh crocodile” or “SuperCroc.” This enormous reptile lived during the Early Cretaceous period, approximately 112 million years ago, primarily in what is now Africa. Reaching an estimated length of 39-40 feet (12 meters) and weighing up to 8 tons, Sarcosuchus dwarfed even the largest modern crocodiles. Its massive skull, measuring over 6 feet (1.8 meters) long, housed more than 100 teeth and generated bite forces powerful enough to crush bones. Particularly distinctive was its expanded bulla at the end of the snout, which may have enhanced its sense of smell or been used for vocalizations. Fossil evidence suggests that Sarcosuchus likely preyed on fish and dinosaurs that came to the water’s edge, including iguanodontids and spinosaurids that shared its habitat.

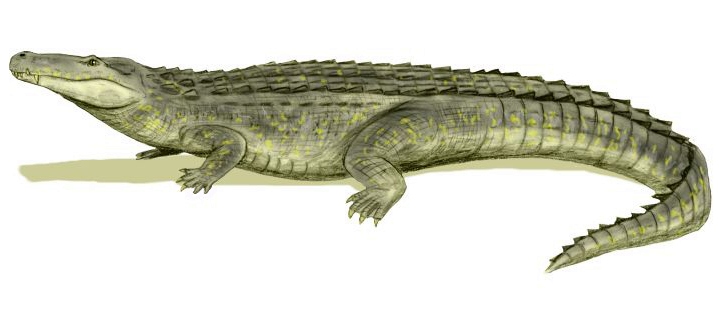

Deinosuchus: Terror of North America

Deinosuchus, meaning “terrible crocodile,” was another fearsome giant that terrorized coastal regions of North America during the Late Cretaceous period, between 82 and 73 million years ago. This massive alligatoroid reached lengths of 33-39 feet (10-12 meters) and may have weighed up to 5-10 tons. Its enormous skull featured robust, blunt teeth perfect for crushing prey, including marine turtles whose shells bear distinctive Deinosuchus bite marks. Paleontologists have uncovered compelling evidence that Deinosuchus preyed on dinosaurs, including bite marks on dinosaur bones and even a partially digested dinosaur bone found within fossilized Deinosuchus stomach contents. Unlike some other giant crocodilians, Deinosuchus had a relatively short, broad snout more similar to modern alligators, suggesting it was an ambush predator that could burst from the water to capture unwary dinosaurs at the shoreline.

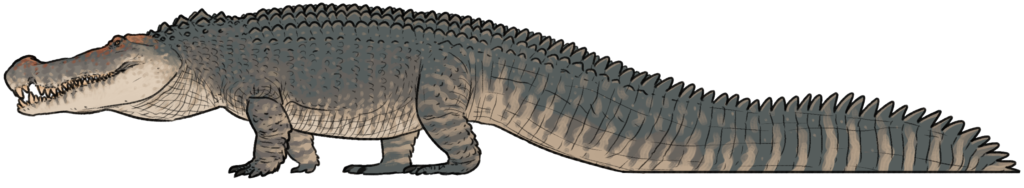

Purussaurus: Amazon’s Ancient Giant

Though slightly younger than the true dinosaur era, Purussaurus brasiliensis deserves mention as possibly the largest crocodilian that ever lived. This massive caiman relative inhabited the wetlands of the Amazon region during the Late Miocene, approximately 8 million years ago. With an estimated length of up to 41 feet (12.5 meters) and weighing potentially 8-11 tons, Purussaurus possessed a skull nearly 5.9 feet (1.8 meters) long. Its wide, robust jaws could generate an estimated bite force of 69,000 newtons (7 tons-force), one of the strongest ever calculated for any animal. This incredible power would have allowed Purussaurus to attack and dismember giant prehistoric relatives of capybaras, ground sloths, and other large mammals that dominated South America during this period. While not contemporaneous with dinosaurs, Purussaurus represents the apex of crocodilian evolution in terms of size and predatory capability.

Hunting Strategies and Adaptations

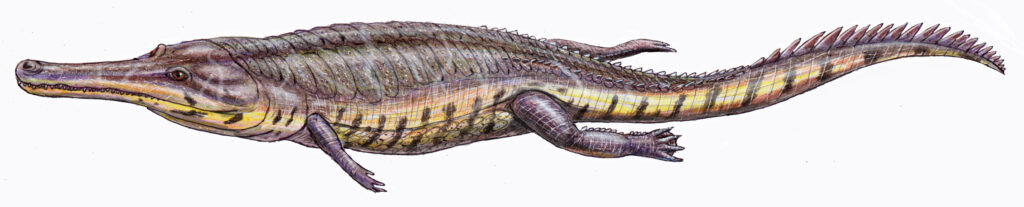

Giant crocodilians employed hunting strategies remarkably similar to those of their modern descendants, though often on a more terrifying scale. Their primary hunting technique was likely the ambush, lying submerged with only their eyes, nostrils, and part of their snout visible at the water’s surface. When dinosaurs or other prey came to drink, these massive predators would explode from the water with incredible speed, grabbing victims with their powerful jaws. Skeletal adaptations reveal that many giant crocodilians had reinforced skulls to withstand the immense forces generated during prey capture and the infamous “death roll” technique used to dismember large prey. Their powerful tails provided explosive acceleration in water, while their semi-aquatic lifestyle gave them an advantage over purely terrestrial dinosaurs at the water’s edge. Some species showed adaptations for different hunting styles—Sarcosuchus had a long, narrow snout suited for fishing, while Deinosuchus had a broader snout better adapted for taking larger prey.

Evidence of Dinosaur Predation

Compelling physical evidence confirms that giant crocodilians preyed on dinosaurs. Paleontologists have discovered dinosaur bones bearing distinctive crocodilian bite marks, characterized by deep punctures and sometimes scrape marks from being dragged into water. In some remarkable finds, partially digested dinosaur remains have been discovered within fossilized crocodilian stomach contents. The bite force calculations for giants like Deinosuchus and Sarcosuchus indicate they could easily crush the bones of many dinosaur species. Further evidence comes from coprolites (fossilized feces) containing dinosaur bone fragments. One particularly dramatic fossil discovery from Madagascar shows a small dinosaur with crocodilian tooth marks, suggesting it was killed but not consumed, possibly indicating a territorial attack rather than predation. Together, these lines of evidence paint a clear picture that giant crocodilians were effective dinosaur predators when the opportunity presented itself.

Baurusuchus: The “Land Crocodile”

Not all dinosaur-hunting crocodilians were semi-aquatic giants. Baurusuchus, whose name means “Bauru crocodile” (named after the Bauru Formation in Brazil where it was discovered), represents a fascinating departure from the typical crocodilian body plan. This 8-10 foot (2.5-3 meter) predator lived during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 90 million years ago, and unlike most crocodilians, was primarily terrestrial. Baurusuchus had long legs positioned directly beneath its body rather than splayed to the sides, allowing it to run efficiently on land, possibly even galloping. Its skull was tall and narrow, with serrated, blade-like teeth more reminiscent of carnivorous dinosaurs than typical crocodilians. These adaptations made Baurusuchus a direct competitor with small to medium-sized theropod dinosaurs, hunting prey on land rather than from water. This convergent evolution with dinosaurian predators demonstrates the remarkable adaptability of the crocodyliform lineage.

Prehistoric Ecological Niches

Giant crocodilians occupied crucial ecological niches in Mesozoic ecosystems, often serving as apex predators in waterways and coastal regions. Their presence influenced the behavior of dinosaurs and other animals, creating “landscapes of fear” around water sources. In some ecosystems, crocodilians dominated aquatic environments while dinosaurs controlled terrestrial habitats, creating a complex predator-prey relationship at the water’s edge. This ecological segregation allowed both groups to thrive in the same regions without direct competition for resources. Fossil evidence suggests that some ecosystems supported multiple crocodilian species simultaneously, with different species specialized for different prey types—some focusing on fish, others on turtles, and the largest species occasionally taking dinosaurs. This niche partitioning, along with their semi-aquatic lifestyle, may help explain how crocodilians survived the end-Cretaceous extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago.

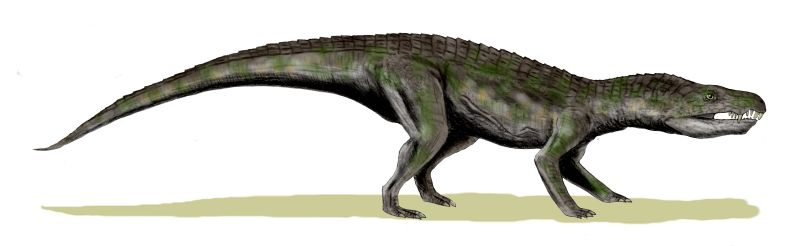

Kaprosuchus: The “Boar Crocodile”

Among the most bizarre dinosaur-era crocodilians was Kaprosuchus saharicus, nicknamed the “boar crocodile” or “BoarCroc.” This unusual predator lived approximately 95 million years ago in what is now Niger, Africa. Unlike typical crocodilians, Kaprosuchus had three pairs of tusk-like teeth that protruded from its jaws when closed, reminiscent of a wild boar’s tusks. Growing to about 20 feet (6 meters) in length, it had long legs positioned directly under its body, suggesting it was primarily terrestrial and capable of galloping at high speeds. Its skull featured bony knobs over the eyes and an unusually deep snout reinforced for powerful biting. These adaptations suggest Kaprosuchus was an active predator that likely hunted dinosaurs on land rather than ambushing them from water. Although smaller than giants like Sarcosuchus, Kaprosuchus represents the remarkable diversity of crocodyliform hunting strategies that evolved during the dinosaur era.

Machimosaurus: The Marine Dinosaur Hunter

Not all giant crocodilians that encountered dinosaurs lived in freshwater—some specialized in marine environments. Machimosaurus was a genus of massive teleosaurid crocodylomorphs that lived during the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous periods, approximately 155-130 million years ago. The largest species, Machimosaurus rex, reached lengths of 30-32 feet (9-10 meters), making it one of the largest marine crocodilians ever discovered. Machimosaurus had a relatively short, robust snout filled with blunt, crushing teeth perfectly adapted for breaking through the shells of marine turtles and ammonites. Though primarily marine, these giants likely encountered coastal dinosaurs, particularly those that ventured into shallow waters. Fossil evidence suggests that Machimosaurus could have preyed on small to medium-sized dinosaurs that ventured into its coastal domain. Its massive size and powerful jaws would have made it a formidable predator capable of attacking even large prey animals, including certain dinosaur species that inhabited coastal environments.

Razanandrongobe: The Dinosaur-Like Crocodilian

Perhaps the most dinosaur-like of all crocodilians was Razanandrongobe sakalavae, nicknamed “Razana.” This massive predator lived during the Middle Jurassic period, approximately 167 million years ago, in what is now Madagascar. Recent fossil analysis has confirmed that Razana was a notosuchian crocodylomorph rather than a theropod dinosaur as initially suspected. This confusion is understandable, as Razana possessed numerous dinosaur-like features, including serrated, ziphodont teeth similar to those of large carnivorous dinosaurs, and possibly a fully terrestrial lifestyle. With an estimated body length of 13-23 feet (4-7 meters) and a massive skull measuring about 2.6 feet (80 cm) long, Razana was among the largest predators in its ecosystem. Its jaws contained teeth designed for slicing rather than the conical piercing teeth of typical crocodilians. These adaptations suggest that Razana actively competed with and hunted dinosaurs on land, taking a predatory niche typically occupied by large theropods.

Surviving the K-Pg Extinction

One of the most remarkable aspects of the crocodilian lineage is that while non-avian dinosaurs went extinct during the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event approximately 66 million years ago, crocodilians survived. This differential survival provides important insights into both groups’ biology and the nature of the extinction event itself. Several factors likely contributed to crocodilian survival. Their semi-aquatic lifestyle provided a buffer against the immediate effects of the asteroid impact and subsequent environmental changes. Their poikilothermic (cold-blooded) metabolism allowed them to survive on minimal food for extended periods, unlike the likely warm-blooded dinosaurs with higher energy requirements. Additionally, crocodilians had broader dietary flexibility, able to consume virtually any animal matter, including carrion. Juvenile crocodilians are also relatively small, requiring less food than juvenile dinosaurs of similar adult size. These adaptations allowed crocodilian lineages to persist through the extinction bottleneck, though many of the giant forms did disappear, with smaller species ultimately becoming the ancestors of modern crocodilians.

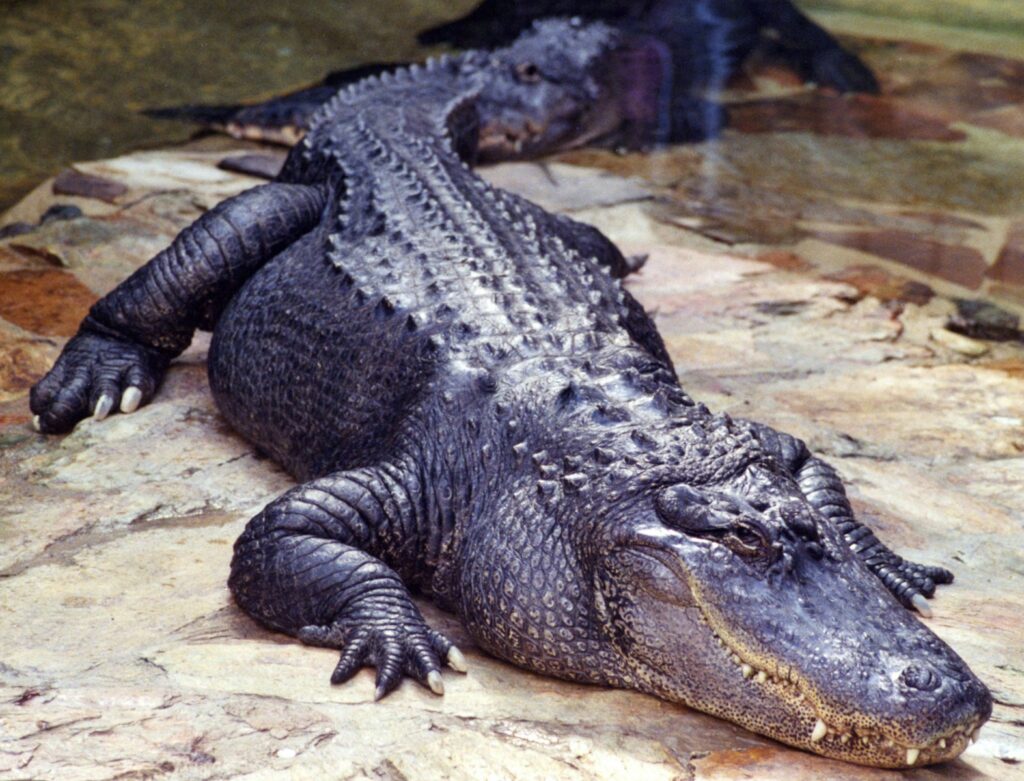

Modern Relatives and Legacy

Today’s crocodilians—including crocodiles, alligators, caimans, and gharials—are the living descendants of the lineage that once produced dinosaur-hunting giants. Modern crocodilians retain many of the same hunting strategies and adaptations that made their ancestors successful, though on a more modest scale. The saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), the largest living reptile, can reach lengths of about 20 feet (6 meters) and weights of 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg)—impressive, but only half the size of giants like Sarcosuchus or Deinosuchus. Modern crocodilians continue to be ambush predators that use water as their hunting domain, though none prey on animals as large as dinosaurs. The study of giant prehistoric crocodilians has important implications for understanding evolutionary patterns, including convergent evolution, niche partitioning, and the factors that drive gigantism in animal lineages. These ancient giants also provide crucial insights into Mesozoic ecosystems and predator-prey relationships, helping scientists better understand the complex world in which dinosaurs lived and the diverse threats they faced.

Conclusion: Lords of the Prehistoric Waters

The giant crocodilians that hunted dinosaurs represent an extraordinary chapter in Earth’s evolutionary history—a time when massive reptilian predators dominated waterways and challenged even the largest dinosaurs. From the bone-crushing Deinosuchus to the bizarre tusked Kaprosuchus, these creatures evolved remarkable adaptations for predation on an epic scale. Their fossils tell stories of dramatic predator-prey interactions, with bite marks on dinosaur bones serving as direct evidence of these ancient confrontations. While most of these giants disappeared millions of years ago, their legacy continues in modern crocodilians, which retain many of the same hunting strategies that made their ancestors such successful predators. As paleontologists continue to unearth new fossils and apply advanced analytical techniques, our understanding of these magnificent predators grows, revealing an increasingly complex picture of life during the Age of Dinosaurs—an era when the line between predator and prey was often determined not by taxonomic classification, but by which animal controlled the critical boundary between land and water.