While dinosaurs vanished from Earth 66 million years ago, their contemporaries—the crocodilians—continue to thrive in modern ecosystems. These remarkable reptiles have maintained their basic body plan for over 200 million years, earning them the title of “living fossils.” The story of how crocodiles survived multiple mass extinctions while dinosaurs perished is a fascinating tale of evolutionary resilience and adaptation. Through a combination of specialized anatomy, behavioral flexibility, and ecological adaptability, crocodilians have persisted through dramatic changes in Earth’s climate and ecosystems. Their journey from the Mesozoic Era to the present day offers valuable insights into evolutionary processes and the mysterious factors that determine which species endure and which disappear into extinction.

Ancient Origins: The Crocodilian Lineage

Crocodilians belong to the archosaur clade, the same evolutionary branch that gave rise to dinosaurs and eventually birds. The first proto-crocodilians appeared during the Late Triassic period, approximately 230 million years ago, evolving from more terrestrial ancestors called pseudosuchians. These early crocodile relatives were diverse in form and ecological niche, with many species being fully terrestrial and some even adopting bipedal locomotion. The lineage that would lead to modern crocodilians—the Crocodylomorpha—emerged around 225 million years ago, gradually developing the semi-aquatic lifestyle and body plan we recognize today. Through millions of years of evolutionary refinement, the group diversified into numerous species that occupied various ecological niches across the ancient world, setting the stage for their remarkable survival story.

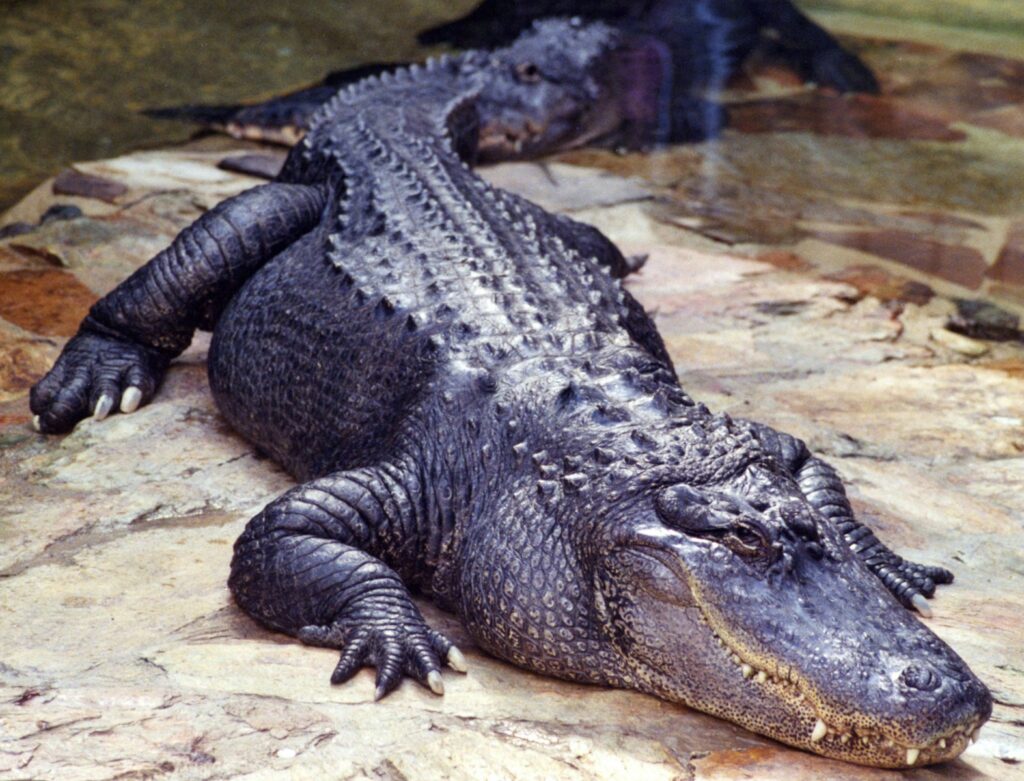

Anatomy Built to Last: Crocodilian Body Plan

The fundamental crocodilian body plan has remained remarkably consistent for over 200 million years, demonstrating the effectiveness of their design for their semi-aquatic predatory lifestyle. Their elongated snouts house powerful jaws with conical teeth designed for gripping prey, while their eyes, ears, and nostrils are positioned on top of their heads to allow them to remain submerged while still sensing their environment. Their streamlined bodies feature powerful tails that serve as both propulsion mechanisms in water and defensive weapons on land. The distinctive armor of overlapping osteoderms (bony plates) beneath their skin protects while allowing flexibility and contributing to thermoregulation. This anatomical blueprint has proven so successful that it has required only minor modifications throughout the eons, allowing crocodilians to maintain their ecological role as apex predators in wetland environments across geological epochs.

Surviving the K-Pg Extinction Event

The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago presented a monumental challenge for all life on Earth. This catastrophic event, triggered by an asteroid impact and exacerbated by volcanic activity, eliminated approximately 75% of all species. Crocodilians, however, managed to survive where many other reptilian groups failed. Their survival can be attributed to several key adaptations, including their semi-aquatic lifestyle, which buffered them from the immediate effects of the impact and subsequent environmental changes. Their ability to remain submerged for extended periods may have protected them from the initial heat pulse following the impact. Additionally, crocodilians’ capacity for metabolic dormancy—slowing their metabolism during food scarcity—allowed them to endure the prolonged period of reduced primary productivity that followed. Their opportunistic feeding habits, capable of sustaining themselves on carrion during times of scarcity, likely contributed to their ability to persist through this evolutionary bottleneck.

Metabolic Advantages: The Cold-Blooded Edge

One of crocodilians’ most significant evolutionary advantages has been their ectothermic (cold-blooded) metabolism, which provides substantial benefits during periods of environmental stress. Unlike endothermic mammals and birds that require constant fuel to maintain body temperature, crocodilians can survive for extended periods, sometimes more than a year, without food by dramatically lowering their metabolic rate. This metabolic flexibility allowed crocodilians to endure prolonged periods of food scarcity that would have proven fatal to many endothermic animals. Their efficient energy utilization means they convert a much higher percentage of consumed calories into body mass compared to endothermic animals. Interestingly, research suggests that early crocodylomorphs may have possessed higher metabolic rates than modern forms, with the shift toward the extreme metabolic efficiency seen in extant species representing an adaptation to their semi-aquatic ambush predator lifestyle. This metabolic strategy, while limiting activity levels, has proven remarkably successful for long-term evolutionary survival.

Habitat Versatility Through Time

Crocodilians have demonstrated remarkable ecological versatility throughout their evolutionary history, adapting to shifting habitats as continental configurations and global climates changed. The fossil record reveals crocodylomorphs thriving in environments ranging from fully marine settings to freshwater systems and even terrestrial habitats. During warmer periods of Earth’s history, crocodilians expanded their range to higher latitudes, with fossils discovered in polar regions that were once warm enough to support these predominantly tropical reptiles. When global cooling trends emerged, crocodilians retreated toward equatorial regions but maintained strongholds in tropical and subtropical aquatic ecosystems. Their semi-aquatic lifestyle has provided consistent access to water, an essential buffer against temperature extremes, and a reliable source of prey. This ecological flexibility has allowed crocodilians to persist through dramatic shifts in Earth’s climate that proved insurmountable for many other reptilian groups, including the non-avian dinosaurs.

Reproductive Strategies for Long-Term Survival

Crocodilian reproductive biology has contributed significantly to their evolutionary longevity through a combination of high reproductive output and parental care. Female crocodilians typically lay between 20-60 eggs per clutch, ensuring that even with high mortality rates, some offspring survive to maintain the population. Unlike many reptiles that abandon their eggs, crocodilians exhibit sophisticated maternal behaviors, with females guarding their nests against predators throughout the incubation period. After hatching, mothers respond to the vocalizations of their young, helping them emerge from the nest and transporting them safely to water in their mouths. This parental protection continues for several months to over a year in some species, substantially improving offspring survival rates. Temperature-dependent sex determination, while potentially vulnerable to climate change, has historically allowed crocodilian populations to maintain appropriate sex ratios across varying environmental conditions, further contributing to their evolutionary resilience.

Behavioral Adaptability and Intelligence

Contrary to their reputation as primitive creatures, crocodilians display sophisticated behaviors and cognitive abilities that have contributed to their evolutionary success. Research has revealed that crocodilians use tools, such as balancing sticks on their snouts to lure nesting birds, and engage in cooperative hunting strategies in some contexts. They exhibit complex social behaviors, including hierarchical structures within populations and sophisticated communication through vocalizations, body postures, and chemical signals. Their brains, while differing in structure from mammalian brains, show specialized adaptations for their ecological niche and support learning and memory capabilities. This behavioral flexibility has allowed crocodilians to adjust their strategies as environments and prey species changed over geological time. Their ability to learn from experience and adapt their behaviors accordingly has provided a crucial advantage in their long evolutionary journey, allowing them to persist where more specialized predators failed.

Diversification Throughout the Ages

The crocodylomorph lineage has undergone remarkable diversification throughout its evolutionary history, producing an array of forms far more varied than today’s crocodilians. During the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, the group included fully marine forms like Metriorhynchids, which evolved dolphin-like bodies with paddle-shaped limbs and tail fins for life in open oceans. Other lineages produced small, fleet-footed terrestrial forms with longer legs adapted for running, and some even developed herbivorous diets with specialized dentition for processing plant material. The Notosuchia included bizarre forms like Simosuchus, with a blunt snout and leaf-shaped teeth adapted for plant consumption, while others like Baurusuchus were fully terrestrial ambush predators with blade-like teeth. This remarkable adaptive radiation demonstrates the evolutionary potential within the crocodilian blueprint. While modern crocodilians represent only a fraction of this ancient diversity, they descend from the lineages that proved most resilient to changing conditions, retaining the fundamental adaptations that have ensured their survival across geological epochs.

Comparisons with Dinosaurian Relatives

Crocodilians and dinosaurs shared a common ancestor approximately 250 million years ago, both belonging to the archosaur clade that dominated terrestrial ecosystems throughout the Mesozoic Era. While dinosaurs evolved toward primarily terrestrial lifestyles, crocodylomorphs diversified into the range of forms discussed previously. The fundamental question of why crocodilians survived the K-Pg extinction while non-avian dinosaurs perished likely relates to their different ecological adaptations and physiological requirements. Dinosaurs, particularly the larger forms, required substantial and consistent food resources to maintain their endothermic or mesothermic metabolisms, making them vulnerable to the collapse of terrestrial food webs following the asteroid impact. In contrast, crocodilians’ ectothermic metabolism and semi-aquatic lifestyle buffered them from these effects. Aquatic ecosystems, while affected by the extinction event, provided more stable refuges than terrestrial environments, allowing crocodilians to persist while their dinosaurian cousins, except birds, disappeared from Earth’s ecosystems.

Genetic Conservation and Evolutionary Stasis

The genetic basis for crocodilians’ evolutionary stability has fascinated scientists studying these living fossils. Genome sequencing of various crocodilian species has revealed remarkably slow rates of molecular evolution compared to other vertebrates, with fewer mutations accumulating over time. This genomic conservation may contribute to the morphological stability observed in the group over millions of years. Research suggests that certain regulatory genes controlling development have remained particularly stable, preserving the basic body plan that has proven so successful. However, this genomic stability does not indicate a complete lack of evolution—crocodilians have continued to adapt at the molecular level to changing environmental pressures while maintaining their fundamental form. The selective pressures on semi-aquatic apex predators appear to have remained relatively consistent across geological time, favoring conservation of traits rather than dramatic innovation. This example of evolutionary stasis demonstrates that sometimes the most successful strategy for long-term survival is refining an already effective design rather than radical reinvention.

Modern Crocodilian Diversity

Today’s crocodilians represent the surviving branches of a once much more diverse evolutionary tree, comprising 24 recognized species across three families. The Crocodylidae includes the true crocodiles, such as the Nile crocodile and saltwater crocodile, which tend to be more tolerant of saltwater environments. The Alligatoridae encompasses alligators and caimans, generally found in freshwater habitats and distinguished by their broader snouts and dental arrangement where lower teeth are mostly hidden when the mouth is closed. The Gavialidae consists solely of the gharial and false gharial, specialized fish-eaters with extremely slender snouts adapted for capturing prey in aquatic environments. Though modest in species count compared to their historical diversity, modern crocodilians occupy crucial ecological roles across tropical and subtropical ecosystems worldwide. Their current distribution spans Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas, with each species adapted to specific local conditions while maintaining the fundamental crocodilian blueprint that has ensured their evolutionary success for over 200 million years.

Conservation Challenges in the Anthropocene

Despite surviving multiple mass extinctions and 200 million years of environmental changes, many crocodilian species now face their greatest challenge: human activity. Historically hunted for their valuable skins and as perceived threats to human communities, numerous crocodilian populations were decimated during the 20th century. Habitat destruction through wetland drainage, river regulation, and coastal development continues to threaten remaining populations by fragmenting their habitats and disrupting breeding areas. Climate change poses additional challenges through altered rainfall patterns, increased temperatures affecting sex ratios in species with temperature-dependent sex determination, and rising sea levels threatening coastal habitats. Pollution, particularly agricultural runoff and industrial contaminants, impacts both crocodilians and their prey species. While conservation efforts have successfully recovered some species, such as the American alligator and saltwater crocodile, from the brink of extinction, eight crocodilian species remain critically endangered. The irony is stark: after surviving the cataclysm that eliminated dinosaurs and persisting through countless environmental changes, these evolutionary marathoners may be undone by the activities of a single species that has existed for a mere fraction of their tenure on Earth.

Lessons from Evolutionary Survivors

Crocodilians offer profound insights into evolutionary processes and the factors that determine long-term survival in Earth’s ever-changing environments. Their persistence demonstrates the value of adaptable, generalist strategies over extreme specialization, which can become an evolutionary liability when conditions change. The effectiveness of their basic body plan—essentially unchanged for 200 million years—challenges the assumption that constant innovation is necessary for evolutionary success. Their example suggests that once a highly effective adaptation evolves, selection may favor refinement rather than reinvention. Crocodilians also illustrate the importance of metabolic efficiency and behavioral flexibility in navigating environmental challenges, from dramatic climate shifts to changes in available prey. Perhaps most significantly, their survival through multiple mass extinctions, including the one that eliminated non-avian dinosaurs, highlights how certain ecological niches and life strategies prove more resilient to planetary crises than others. As humanity faces self-inflicted environmental challenges of potentially extinction-level magnitude, the evolutionary wisdom embodied in these ancient survivors merits our attention and respect.

How Crocodiles Outlasted Dinosaurs and Defied Extinction

The story of crocodilians—from their emergence alongside early dinosaurs to their continued presence in modern ecosystems—represents one of evolution’s most remarkable success stories. Their ability to weather environmental catastrophes that claimed countless other lineages testifies to the effectiveness of their adaptations and life strategy. While often portrayed as primitive or unchanged, crocodilians are better understood as perfectly refined—their apparent stability reflecting not evolutionary stagnation but rather the enduring success of their fundamental design. As we face an uncertain environmental future, these living fossils remind us of nature’s resilience while simultaneously warning us that even the most successful evolutionary lineages have their limits. After 200 million years of overcoming everything nature could throw at them, crocodilians’ greatest challenge may be surviving the impact of humanity by the very species now studying their remarkable evolutionary journey.