When a massive asteroid struck Earth approximately 66 million years ago, it triggered catastrophic global changes that wiped out approximately 75% of all species, including the non-avian dinosaurs that had dominated terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years. Yet amid this devastation, certain animal groups managed to endure and eventually thrive in the post-impact world. Crocodilians, birds, and turtles stand as living testaments to evolutionary resilience, having weathered one of Earth’s most devastating extinction events. Their survival strategies and adaptations offer fascinating insights into how life persists through planetary disasters.

The Chicxulub Impact: A Global Catastrophe

The asteroid that struck near the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico created an immediate hellscape of tsunamis, wildfires, and a global darkness that lasted for months or years. The Chicxulub impactor, estimated to be about 10-15 kilometers in diameter, released energy equivalent to billions of Hiroshima bombs upon impact. This cataclysmic event vaporized rock and sent it into the atmosphere, creating a thermal pulse that ignited global wildfires. Sulfur-rich rocks at the impact site released aerosols that blocked sunlight, causing a nuclear winter effect that suppressed photosynthesis worldwide. The resulting collapse of food webs eliminated approximately three-quarters of all plant and animal species on Earth, marking the end of the Cretaceous period and beginning the Cenozoic era we live in today.

Birds: The Dinosaurs That Survived

Birds represent the only dinosaur lineage that survived the mass extinction, making them living dinosaurs in the truest sense. Research suggests that the ancestors of modern birds possessed several adaptations that proved crucial for survival. Their relatively small body sizes required less food than their larger dinosaur relatives, allowing them to subsist on limited resources during the post-impact famine. Many early birds had also evolved specialized beaks that could crack seeds—a significant advantage when global forests were decimated and seeds remained as dormant food sources. Additionally, some evidence suggests that the surviving bird lineages may have already developed the ability to forage on the ground rather than being exclusively tree-dwelling, which would have been advantageous when forests were devastated by wildfires and prolonged darkness.

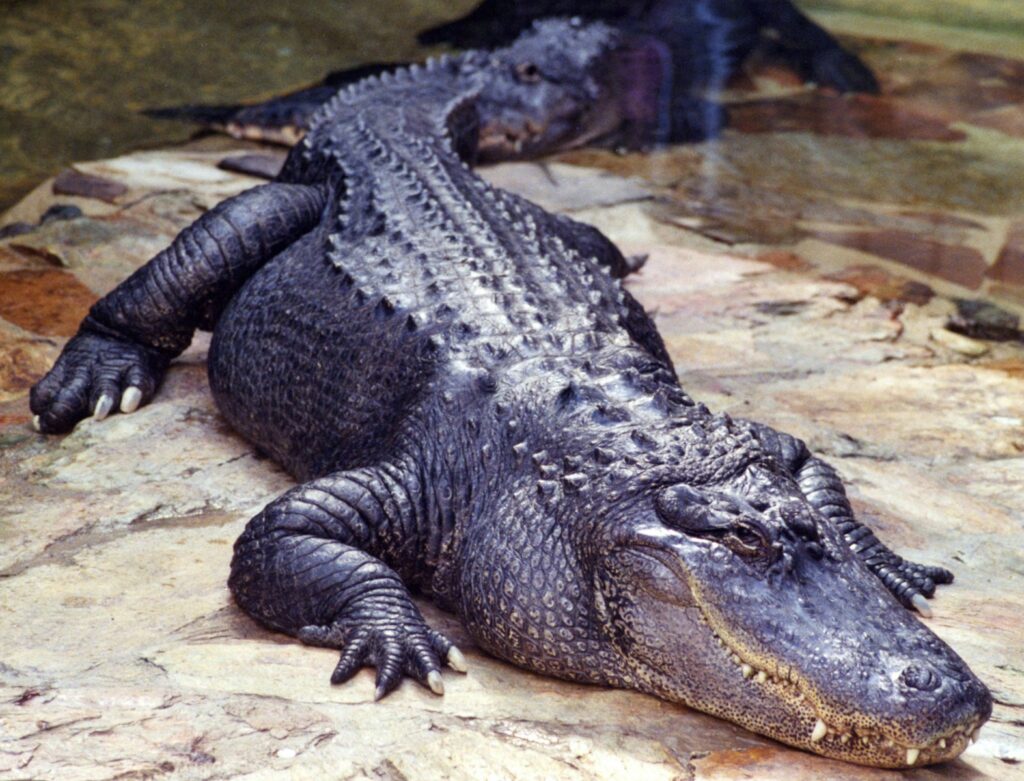

Crocodilians: Masters of Aquatic Adaptation

Crocodilians represent one of evolution’s greatest success stories, having survived virtually unchanged for over 200 million years through multiple mass extinctions. Their semi-aquatic lifestyle provided crucial protection during the immediate aftermath of the asteroid strike. Water bodies acted as buffers against the extreme temperature fluctuations and wildfires that ravaged terrestrial environments. Moreover, crocodilians possess remarkable metabolic adaptations that proved life-saving during the food-scarce post-impact years. Their ability to slow their metabolism dramatically allows them to survive without food for months or even years in extreme cases. This metabolic flexibility, combined with opportunistic feeding strategies that enable them to consume virtually any available prey, allowed crocodilians to endure conditions that proved fatal to many other large reptiles, including their dinosaur contemporaries.

Turtles: Sheltered from Extinction

Turtles showcase how evolutionary adaptations developed for one purpose can unexpectedly provide survival advantages during catastrophic events. Their protective shells, which evolved primarily as a defense against predators, may have shielded them from the immediate effects of the asteroid impact. Many turtle species are also capable of surviving extended periods without food—some can reduce their metabolic rates by up to 95% during brumation (reptilian hibernation). Aquatic turtles likely benefited from the relative stability of underwater environments during the extinction event. Freshwater ecosystems, while affected by the global catastrophe, generally experienced less dramatic temperature fluctuations than terrestrial habitats. Additionally, many turtle species are omnivorous scavengers with highly adaptable diets, allowing them to utilize whatever food sources remained available in the post-impact environment.

Aquatic Environments as Survival Refuges

Aquatic environments played a crucial role in buffering their inhabitants from the worst effects of the asteroid impact. Water’s high specific heat capacity meant that aquatic habitats experienced less extreme temperature fluctuations compared to land environments. The thermal protection provided by water bodies likely shielded aquatic species from the initial heat pulse that followed the asteroid impact, which is estimated to have raised global temperatures dramatically in the hours and days after the collision. Additionally, aquatic food webs were somewhat less disrupted than terrestrial ones, as they relied less directly on photosynthesis from land plants. Marine algae and phytoplankton, while severely affected, could recover more quickly than terrestrial forests once dust and aerosols began clearing from the atmosphere. This relative stability made aquatic and semi-aquatic lifestyles advantageous during the extinction crisis, benefiting animals like crocodilians and turtles.

Metabolic Adaptations: The Key to Survival

Perhaps the most crucial adaptation shared by crocodilians, birds, and turtles was their ability to adjust their metabolic rates in response to environmental conditions. Modern crocodilians can reduce their metabolism dramatically during periods of food scarcity, with some species capable of surviving more than a year without eating. Similarly, many turtle species enter brumation states during harsh conditions, significantly reducing their energy requirements. Birds, despite being warm-blooded, possess metabolic flexibility that their larger dinosaur relatives lacked. Some modern birds can enter torpor states to conserve energy during food shortages—a trait that may have evolved in their pre-extinction ancestors. This metabolic plasticity would have been invaluable during the years of darkness and reduced plant productivity that followed the asteroid impact. While large dinosaurs required constant food intake to maintain their massive bodies, these more metabolically flexible animals could endure extended periods of resource scarcity.

Behavioral Adaptations: Finding Opportunity in Crisis

Behavioral adaptations complemented physiological ones in helping certain species survive the mass extinction. Evidence suggests that the bird lineages that survived the asteroid impact were ground-foragers rather than tree-dwelling specialists. When forests were decimated by wildfires and subsequent climate changes, these ground-adapted birds could continue finding food in open environments. Many turtles and crocodilians display opportunistic feeding behaviors, allowing them to switch food sources based on availability—a crucial trait when preferred prey species were disappearing. Burrowing behaviors may have also protected some animals from the immediate effects of the impact. Recent fossil evidence indicates that some early mammals, turtles, and other vertebrates could have sheltered underground during the most severe environmental disruptions. These behavioral adaptations, combined with physiological resilience, created multiple survival pathways through the extinction bottleneck for these successful groups.

Dietary Flexibility as a Survival Strategy

Animals with specialized diets faced greater extinction risks than omnivores and dietary generalists during the mass extinction event. The collapse of plant communities following the asteroid impact created cascading effects through food webs, eliminating many specialist feeders. Crocodilians exemplify dietary opportunism—modern species are known to consume virtually anything they can capture, from fish and mammals to mollusks and carrion. This feeding flexibility would have been invaluable when preferred prey became scarce. Similarly, many turtle species are omnivorous, consuming both plant material and animal protein depending on availability. The early birds that survived the extinction appear to have been seed-eaters or omnivores rather than insect specialists. Seeds represent concentrated, storable energy packets that can remain viable in soil for extended periods, providing a crucial food resource when active plant growth was suppressed by post-impact climate changes. This dietary flexibility allowed these animals to utilize whatever food sources remained available during the extinction crisis.

Size Matters: The Advantage of Being Small

The fossil record clearly demonstrates that the K-Pg (Cretaceous-Paleogene) extinction preferentially eliminated larger animals, particularly those weighing more than 25 kilograms. This size-selective extinction pattern offered an advantage to relatively smaller species with lower absolute energy requirements. Large dinosaurs needed constant and substantial food intake to maintain their massive bodies, making them vulnerable when plant productivity collapsed following the asteroid impact. In contrast, smaller animals could survive on less food and often had more diverse feeding options. The birds that survived were among the smallest dinosaurs of their time, with body masses likely under 1 kilogram. While some crocodilian and turtle species were relatively large, they compensated with their ability to dramatically reduce metabolism during food shortages. This “size filter” effect of the extinction fundamentally reshaped terrestrial ecosystems, eliminating the dominance of large dinosaurs and creating ecological opportunities that would eventually be filled by mammals in the Cenozoic era.

Reproductive Strategies That Enhanced Survival

Reproductive strategies significantly influenced which species survived the mass extinction event. Animals capable of producing numerous offspring quickly had advantages in repopulating after population crashes. Many turtle and crocodilian species lay dozens of eggs per clutch, allowing their populations to potentially recover quickly when conditions improved. Egg-laying itself offered certain advantages during the extinction crisis, as eggs contain yolk reserves that can sustain embryonic development even when environmental food sources are scarce. Additionally, the hard-shelled eggs of birds, crocodilians, and turtles provided protection against environmental contaminants and radiation that may have been present after the asteroid impact. The ability to store sperm and delay egg development until environmental conditions improved—a trait present in many turtles and some birds—would have also been advantageous during periods of extreme environmental stress, allowing reproduction to be synchronized with resource availability.

Post-Extinction Recovery and Radiation

The survival of crocodilians, birds, and turtles through the extinction bottleneck positioned them for evolutionary success in the post-dinosaur world. Birds underwent remarkable adaptive radiation in the early Cenozoic, diversifying into numerous ecological niches that had been vacated by extinct dinosaur lineages and pterosaurs. From the relatively few bird lineages that survived the extinction emerged the incredible diversity of modern birds, comprising over 10,000 species today. Crocodilians, while less diverse in species numbers, maintained their ecological roles as apex predators in freshwater and coastal environments across tropical and subtropical regions. Turtles similarly diversified to occupy various aquatic and terrestrial niches worldwide, with approximately 350 species existing today. The evolutionary history of these groups demonstrates both their remarkable resilience during the extinction event and their subsequent ability to capitalize on ecological opportunities in the recovery period, establishing dynasties that have persisted for 66 million years after the dinosaurs’ demise.

Lessons from Ancient Survivors for Modern Conservation

The survival strategies that helped crocodilians, birds, and turtles endure the asteroid-induced mass extinction offer valuable perspectives for understanding modern biodiversity challenges. Many of these ancient survivors now face significant threats from human activities and climate change. Ironically, traits that once aided their survival—such as the long lifespans and delayed maturity of many turtles and crocodilians—now make their populations vulnerable to human exploitation. Their history demonstrates that even the most resilient groups can face extinction when environmental changes occur too rapidly for adaptation. However, understanding the factors that enabled these animals to survive past catastrophes might inform conservation strategies. Protecting aquatic refuges, maintaining habitat connectivity, and preserving populations large enough to retain genetic diversity could help modern descendants of these ancient survivors endure contemporary environmental changes. Their evolutionary resilience stands as both inspiration and warning as we navigate our current biodiversity crisis.

Conclusion

The survival of crocodilians, birds, and turtles through the catastrophic aftermath of the Chicxulub asteroid impact represents one of evolution’s most remarkable success stories. These diverse animal groups weathered an extinction event that eliminated approximately three-quarters of Earth’s species through a combination of fortunate pre-adaptations, including metabolic flexibility, dietary opportunism, aquatic lifestyles, and appropriate body sizes. Their endurance through this evolutionary bottleneck allowed them to diversify and thrive in the post-dinosaur world, establishing evolutionary lineages that continue to this day. As we face contemporary environmental challenges, these ancient survivors remind us of life’s remarkable resilience while simultaneously underscoring that even the most adaptable groups have limits to what they can withstand. The lessons from these extinction survivors remain relevant as we work to preserve biodiversity through our current human-driven extinction crisis.