For over 165 million years, dinosaurs dominated Earth’s landscapes, yet only recently have we begun to understand the complex parental behaviors these remarkable creatures may have exhibited. Far from the cold, reptilian abandonment once imagined, evidence increasingly suggests many dinosaur species were devoted parents that provided extensive care for their offspring. From nest-building to food provision and protection from predators, dinosaur parenting strategies appear to have been diverse and sophisticated, perhaps rivaling those of modern birds, their closest living relatives. This article explores the fascinating evidence for dinosaur parental care and what it reveals about these ancient animals’ social lives.

The Fossil Evidence: Nests and Egg Clutches

The most direct evidence for dinosaur parental care comes from remarkably preserved fossil nests. Paleontologists have discovered thousands of dinosaur nests worldwide, from Mongolia’s Gobi Desert to Montana’s Two Medicine Formation, containing carefully arranged egg clutches. Many nests show distinct architectural patterns that would have required deliberate construction by adult dinosaurs. For instance, the duck-billed hadrosaur Maiasaura (whose name means “good mother lizard”) created bowl-shaped nests approximately seven feet in diameter with raised rims to prevent eggs from rolling away. Some theropod dinosaurs, like Oviraptor and Troodon, arranged their eggs in circular patterns with the adult positioned centrally, much like modern brooding birds. These organized nest structures strongly suggest intentional design rather than simple egg dumping, indicating a level of parental investment before hatching even occurred.

Brooding Behaviors: Warming the Next Generation

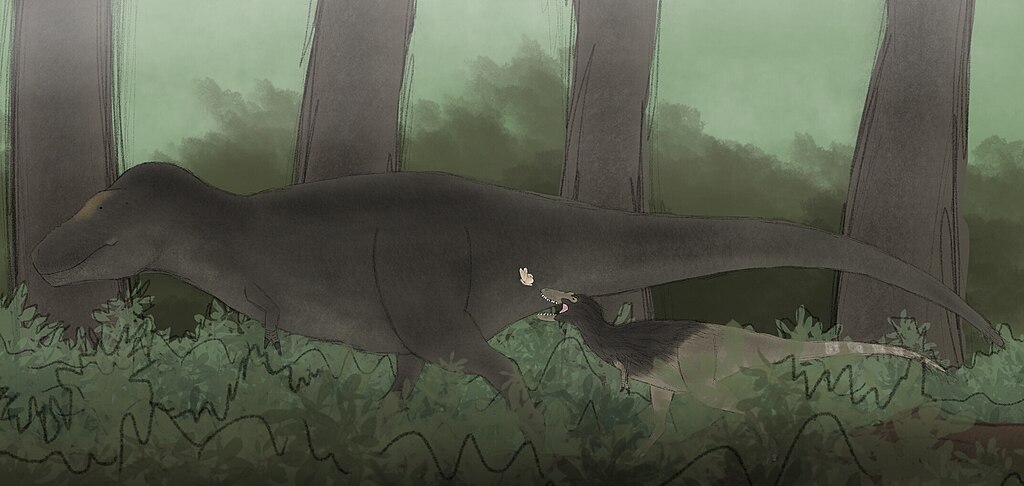

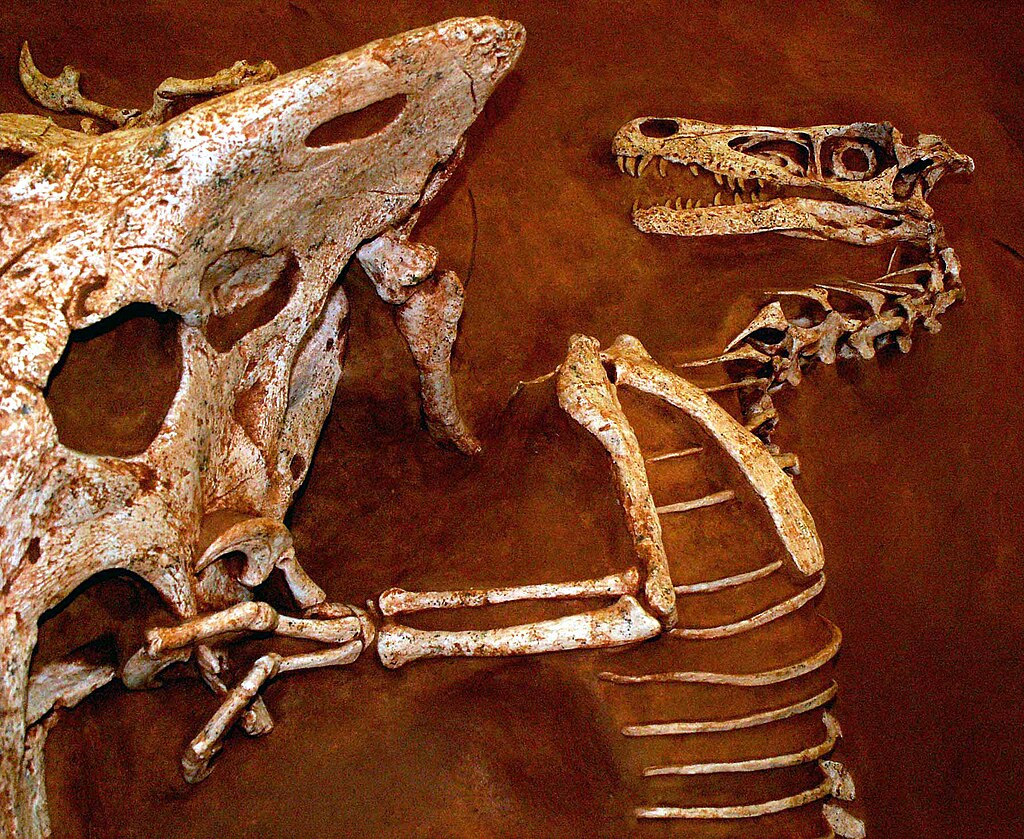

Perhaps the most striking evidence for dinosaur parental care comes from fossils of adult dinosaurs preserved directly atop their nests in brooding postures. The most famous example is the Oviraptor specimen nicknamed “Big Mama,” discovered in Mongolia with its limbs symmetrically arranged around a clutch of eggs. Initially misinterpreted as an egg thief (hence the name “Oviraptor” meaning “egg seizer”), paleontologists now recognize that this dinosaur was protecting its eggs. Similar brooding postures have been found in other small theropods like Citipati and Troodon, with adults positioned with their arms spread over the eggs in a bird-like fashion. The positioning of these adults strongly suggests they were insulating their eggs with body heat and protecting them from environmental hazards and predators. This behavior, virtually identical to modern avian incubation, indicates these dinosaurs made significant time investments in egg care.

Altricial vs. Precocial Young: Different Parenting Strategies

Dinosaur species appear to have developed different strategies regarding offspring development, much like modern animals. Some species produced precocial young—fully developed hatchlings capable of independent movement and feeding shortly after hatching. Evidence for precocial development comes from embryonic remains showing well-developed bones and proportionally large egg sizes that would allow for more development before hatching. Other dinosaur species, particularly some ornithischians like Maiasaura, show evidence of altricial young—hatchlings that were relatively helpless and required extended parental care. Maiasaura nests contain the remains of hatchlings with underdeveloped leg bones, suggesting these babies couldn’t immediately leave the nest and required adult feeding and protection. This fundamental difference in offspring development would have demanded very different parental investment strategies across dinosaur groups, with altricial species requiring much more extensive post-hatching care than their precocial counterparts.

Feeding the Young: Evidence from Bone Microstructure

How dinosaurs fed their young remains one of the most intriguing questions in paleontology, and bone microstructure analysis has provided fascinating insights. By examining the growth lines in fossilized baby dinosaur bones—similar to tree rings—scientists can determine how quickly youngsters grew. Many juvenile dinosaurs show incredibly rapid growth rates that would have been impossible without substantial parental food provision. Baby Maiasaura fossils reveal they doubled in size within weeks of hatching while still nest-bound, suggesting adults must have brought food to the nest. Unlike modern reptiles, which grow slowly and opportunistically, many dinosaur hatchlings grew at rates more similar to birds, whose parents actively feed them. The tooth wear patterns in some juvenile dinosaurs also differ from adults, suggesting different feeding strategies or that parents may have provided pre-processed food to their young, similar to how some modern birds regurgitate partially digested meals for their chicks.

Colony Nesting: Communal Protection Strategies

Many dinosaur species appear to have nested in large colonies, suggesting sophisticated social structures that enhanced offspring survival. Massive nesting grounds containing dozens or even hundreds of nests nearby have been discovered for species ranging from the duck-billed Maiasaura to the horned Protoceratops. These dinosaur “rookeries” closely resemble the colonial nesting behaviors seen in modern birds like penguins or flamingos. The colonial approach likely offered numerous advantages for protecting vulnerable eggs and hatchlings. Adults could potentially take turns guarding groups of nests, allowing others to forage for food. The sheer concentration of vigilant adults would have deterred predators through safety in numbers. Additionally, colonial nesting may have facilitated knowledge transfer between generations as young dinosaurs observed adult behaviors within the colony. The existence of these dinosaur nurseries strongly suggests complex social structures beyond simple individual parenting.

Nest Attendance: How Long Did Parents Stay?

The duration of parental care varied significantly across dinosaur species, with some appearing to provide extended post-hatching supervision. Trackway evidence occasionally shows adult and juvenile footprints in close association, suggesting parents and offspring traveled together for some period after leaving the nest. In the case of Maiasaura, nest sites contain remains of juveniles at different growth stages, indicating they remained in or near the nest while growing to about three feet long, approximately half adult size. This suggests weeks or months of parental attendance, similar to modern ground-nesting birds like emus or rheas. For larger dinosaurs like sauropods, the enormous size difference between hatchlings and adults would have made direct physical care challenging, possibly resulting in more limited attendance. Some theropod dinosaurs may have exhibited the most extended care, as evidenced by family groups preserved together, such as the small ceratopsian Psittacosaurus found fossilized with what appears to be its young clustered around it.

Dinosaur Parenting Among Different Groups

Parental care strategies varied dramatically across the major dinosaur lineages, reflecting their diverse lifestyles and evolutionary relationships. Theropods—the meat-eating dinosaurs that eventually gave rise to birds—show the most bird-like parenting behaviors, including brooding and nest guarding. Small, feathered theropods like Oviraptor and Troodon likely provided the most intensive care, possibly including direct feeding of young. Among herbivorous ornithischians, the hadrosaurs like Maiasaura and Hypacrosaurus show compelling evidence for extended nest care and feeding of altricial young in colonial settings. Ceratopsians, including Protoceratops, left abundant nesting traces suggesting at least egg-tending behaviors. The evidence for sauropod parental care is more limited, with their massive size potentially restricting direct physical care, though they likely selected and prepared nest sites carefully. These variations in care strategies likely evolved in response to different ecological pressures and reproductive strategies, with smaller, more vulnerable species generally showing more intensive parenting behaviors.

The Bird Connection: Evolutionary Roots of Parental Care

The sophisticated parenting behaviors observed in dinosaur fossils make perfect evolutionary sense when we consider that birds are living dinosaurs. Modern birds exhibit some of the animal kingdom’s most dedicated parenting, with behaviors ranging from egg incubation to feeding chicks and teaching survival skills. These traits didn’t appear suddenly with the evolution of birds but were inherited from their dinosaur ancestors. The discovery of brooding behaviors in small theropods like Oviraptor and Troodon—dinosaurs closely related to birds—demonstrates that key aspects of avian parenting were already established in non-avian dinosaurs. Features like nest construction, egg-turning, and brooding postures evolved in dinosaurs millions of years before the first birds appeared. The remarkable similarity between some dinosaur nesting sites and those of ground-nesting birds today suggests a direct evolutionary continuity in reproductive strategies. This connection provides a perfect example of how paleontological discoveries can illuminate evolutionary pathways that connect ancient extinct animals to modern species.

Temperature Regulation and Nest Construction

Dinosaurs invested considerable effort in constructing nests that would maintain optimal incubation temperatures for their eggs. Fossil evidence reveals sophisticated nest designs across different species, from the shallow depressions created by some theropods to the vegetation mounds built by hadrosaurs. Many dinosaurs appear to have used rotting vegetation in their nests, which would have generated heat through decomposition—a strategy still employed by modern crocodilians and some birds like megapodes. Other species relied more on direct body heat, especially the smaller feathered theropods that could effectively insulate their eggs. The orientation and positioning of nests also suggest temperature awareness, with many nests located to maximize sun exposure in cooler environments or positioned for shade in warmer regions. Some dinosaurs, like the duck-billed Maiasaura, created nests with specific soil types that would maintain more stable temperatures. These sophisticated approaches to nest microclimate management demonstrate remarkable parental investment even before hatching occurs.

Parental Defense: Protecting Vulnerable Offspring

The fossil record provides compelling evidence that many dinosaur parents actively defended their young from predators. Some of the most dramatic examples come from ceratopsians like Protoceratops, where adults have been found fossilized in positions suggesting they died while protecting their nests from attackers. The famous “fighting dinosaurs” fossil showing a Velociraptor locked in combat with a Protoceratops may represent an attempted nest raid that ended fatally for both participants. Large body size itself served as a deterrent for many dinosaur species, with massive adults creating a formidable barrier between predators and vulnerable nests or hatchlings. Defense capabilities like the horns of ceratopsians or the tail clubs of ankylosaurs may have evolved partially for offspring protection. Colonial nesting would have enhanced defensive capabilities through collective vigilance, with multiple adults available to respond to threats. The risk of injury or death while defending young represents one of the most significant parental investments, suggesting strong selection pressure for effective protective behaviors in dinosaur parents.

Teaching and Social Learning in Dinosaur Families

Though difficult to preserve in the fossil record, mounting evidence suggests dinosaurs may have engaged in teaching behaviors and social learning within family groups. Trackways occasionally preserve evidence of adults and juveniles moving together, potentially representing teaching moments for behaviors like migration or foraging techniques. The prolonged association between adults and juveniles seen in some species would have provided ample opportunity for young dinosaurs to observe and learn survival skills from experienced parents. In highly social dinosaurs like the duck-billed hadrosaurs or horned ceratopsians, juvenile development appears to have included extended periods within family groups or herds where they could acquire complex social behaviors. The discovery of age-segregated herds in some dinosaur species suggests a structured learning environment where juveniles gradually integrated into adult society. While direct evidence of teaching is necessarily circumstantial, the complex behaviors exhibited by many dinosaurs would have required significant learning periods, just as we see in their modern avian descendants.

Challenges in Studying Dinosaur Parenting

Despite significant advances, paleontologists face substantial challenges when investigating dinosaur parenting behaviors. The fossil record captures only rare moments in time, making it difficult to document extended behavioral sequences or subtle interactions between parents and offspring. Preservation biases favor hard tissues like bones and eggs, while soft tissues that might reveal feeding adaptations rarely fossilize. Behavior itself doesn’t fossilize directly, forcing scientists to make careful inferences based on skeletal evidence, nest structures, and comparisons with modern relatives. Another significant challenge is distinguishing true parental care from other explanations for adult-juvenile associations, such as opportunistic predation or coincidental preservation. The long time spans involved also complicate interpretation, as nests that appear to contain different-aged juveniles might represent sequential nesting events rather than extended family care. Despite these challenges, the cumulative evidence from multiple lines of inquiry—including nest structures, growth rates, and comparative biology—has allowed paleontologists to construct increasingly detailed models of dinosaur parenting behaviors.

Future Research Directions in Dinosaur Parental Care

The study of dinosaur parenting continues to advance through innovative research approaches and new fossil discoveries. Advanced imaging technologies like CT scanning now allow paleontologists to examine dinosaur eggs non-destructively, revealing embryonic development stages and potential adaptations for parental care. Chemical analysis of fossil eggshells and bones can reveal diet and environmental conditions during development, potentially identifying parental feeding signatures. Improved dating techniques help establish more precise timelines for nest usage and juvenile development. Computer modeling of dinosaur biomechanics provides insights into how adults might have physically interacted with eggs and young. Perhaps most promising is the ongoing discovery of new fossil nesting sites worldwide, particularly in previously unexplored regions of Asia, South America, and Africa, which continues to expand our understanding of parenting diversity across dinosaur groups. As research continues, paleontologists hope to answer remaining questions about feeding methods, parental recognition systems, and the possible existence of extended family structures in these remarkable ancient animals.

Conclusion

The fossil evidence increasingly reveals that many dinosaurs were dedicated, attentive parents who invested substantially in their offspring’s survival. From the elaborate nest construction and brooding behaviors of small theropods to the extended care provided in hadrosaur nurseries, dinosaur parenting strategies appear to have been diverse, sophisticated, and adapted to each species’ ecological niche. This parental investment represents an evolutionary bridge between the limited care seen in most reptiles and the intensive parenting characteristic of modern birds. As new fossils and analytical techniques continue to emerge, our understanding of dinosaur family life grows ever richer, transforming our perception of these ancient animals from cold, solitary reptiles to complex social beings embedded in family groups and communities. The dinosaur legacy lives on not just in the bones of museum displays but in the devoted parenting behaviors of the birds that share our world today.