When we think of dinosaurs, our mental images are often shaped by artistic reconstructions seen in museums, books, and films. But how do paleontologists know what dinosaurs looked like on the outside? The secret lies in rare and precious fossil impressions that preserve traces of soft tissues like skin, scales, and feathers. These exceptional fossils, often called “mummies” or impression fossils, offer direct evidence of external features that normally decay long before fossilization occurs. Researchers have dramatically transformed our understanding of dinosaur appearance, biology, and evolution over the past few decades through careful scientific analysis of these impressions.

The Unexpected Preservation of Soft Tissues

The preservation of soft tissues in the fossil record is exceedingly rare, requiring special conditions that prevent normal decomposition. Most dinosaur fossils consist only of mineralized bones, which tell us about skeletal structure but reveal little about external appearance. Soft tissue impressions typically form when a dinosaur’s body is rapidly buried in fine-grained sediment like mud or silt that can capture minute details before decomposition occurs. Sometimes, the body becomes naturally mummified through dehydration before burial, preserving skin impressions in three dimensions. In other cases, chemical conditions in the burial environment, such as high concentrations of iron or lack of oxygen, slow bacterial decay long enough for impressions to form. These exceptional conditions have provided us with fossil impressions from numerous dinosaur groups spanning the Mesozoic Era, offering precious glimpses of their external covering.

Scales: The Classic Dinosaur Covering

Scales represent the ancestral body covering for dinosaurs, and scale impressions have been found in fossils from multiple dinosaur lineages. In hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), remarkable specimens from North America and Asia preserve detailed scale patterns across large portions of the body. These fossils reveal that many hadrosaurs had small, non-overlapping scales arranged in patterns that varied by body region—tiny tubercle-like scales on some areas, and larger polygonal scales on others. Ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs) like Triceratops also possessed scales, with some specimens showing large, shield-like scales interspersed with smaller ones, possibly protecting predators. Sauropod skin impressions, though rarer, indicate these giant dinosaurs had small, bead-like scales arranged in rosette patterns, with no evidence of feathers. These varied scale morphologies suggest that dinosaur skin was not uniform but evolved specific textures and patterns adapted to different ecological niches and functional needs.

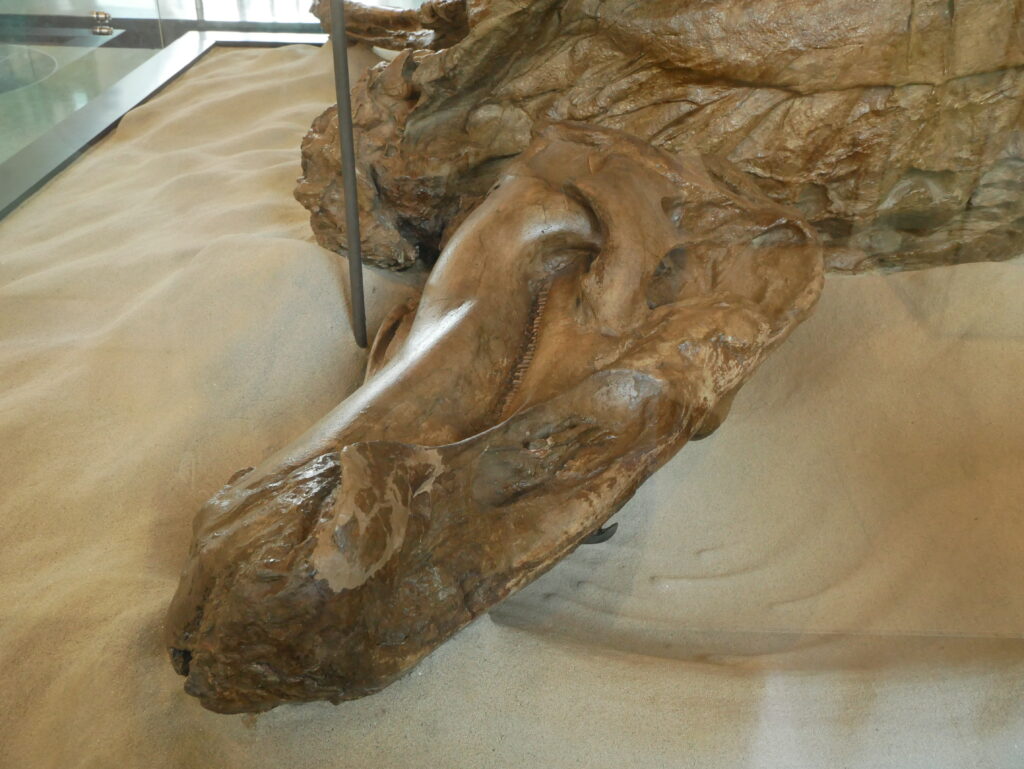

The “Dinosaur Mummies” of North America

Some of the most spectacular dinosaur skin impressions come from naturally mummified specimens found primarily in the Hell Creek and Lance Formations of the western United States. The most famous of these, the “Trachodon mummy” (actually an Edmontosaurus), discovered in 1908 in Wyoming, preserves nearly two-thirds of the animal’s skin impressions, showing remarkable detail in the texture and pattern of its scales. Another exceptional specimen is “Dakota,” a juvenile hadrosaur discovered in North Dakota in 1999, which preserves skin impressions so detailed that researchers could identify the thickness of the skin in different body regions and even analyze its internal structure. These natural mummies form when a dinosaur’s body desiccates rapidly after death, with the skin shrinking around the skeleton, before burial preserves these details. Careful excavation and preparation of these specimens have allowed paleontologists to create accurate life-sized models showing precisely how these dinosaurs appeared in life, complete with skin folds, wrinkles, and scale patterns that would be impossible to deduce from bones alone.

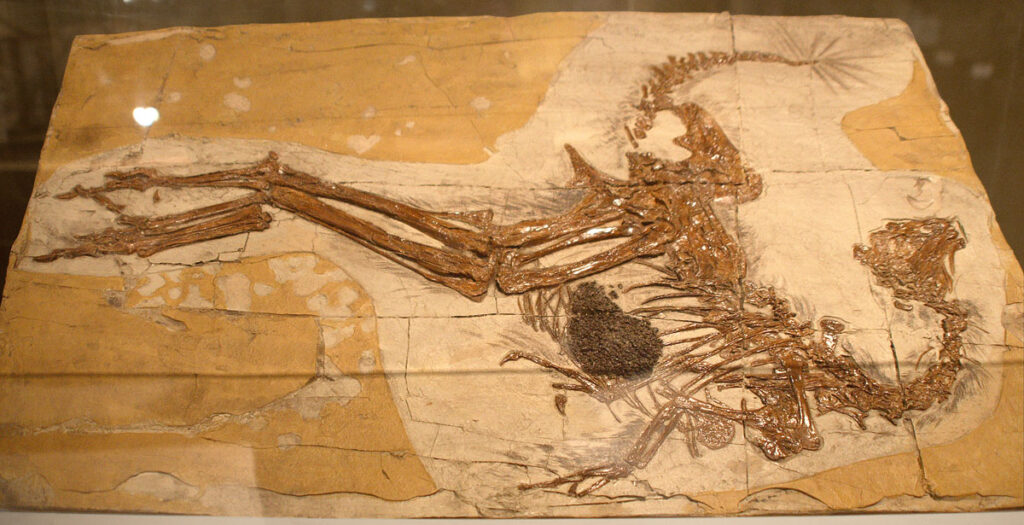

Feather Impressions and the Dinosaur-Bird Connection

The discovery of feathered dinosaur fossils, primarily from the fine-grained limestone deposits of Liaoning Province in China, has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur appearance and evolution. Beginning with the discovery of Sinosauropteryx in 1996, paleontologists have identified more than 30 non-avian dinosaur species with preserved feather impressions. These fossils reveal that many theropod dinosaurs (the group that includes Velociraptor and T. rex) possessed various types of feathery structures, from simple filaments to complex pennaceous feathers similar to those of modern birds. The preservation quality of these fossils is often extraordinary, with some specimens showing different feather types on different parts of the body and even preserving original coloration patterns. These discoveries have provided definitive evidence that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs and that feathers originally evolved for functions other than flight, such as insulation, display, or brooding of eggs, long before they were co-opted for aerial locomotion.

Analyzing the Structure of Dinosaur Feathers

Fossil impressions have allowed scientists to analyze the detailed structure of dinosaur feathers, revealing a surprising diversity of feather types across different species. The simplest type, seen in dinosaurs like Sinosauropteryx, consisted of single filaments resembling fur or down that likely provided insulation. More complex structures appear in maniraptoran dinosaurs, with some species showing branched feathers similar to the downy feathers of modern birds. Some dromaeosaurids and oviraptorosaurs possessed pennaceous feathers with a central shaft and barbs, structurally identical to modern bird feathers. Particularly remarkable are specimens of Microraptor, which show well-preserved flight feathers on both its arms and legs, suggesting it was a four-winged glider. By comparing these structures to modern feathers under electron microscopy, researchers have identified the preservation of melanosomes—tiny cellular structures containing pigment, which has even allowed the reconstruction of original feather colors in some species. These analyses have demonstrated that dinosaur feathers evolved through a series of structural innovations over millions of years before culminating in the flight feathers of birds.

Color Patterns Revealed in Fossilized Skin

One of the most exciting recent developments in paleontology has been the ability to determine the coloration of extinct dinosaurs through microscopic analysis of preserved skin and feathers. This breakthrough relies on the identification of melanosomes, cellular structures that contain melanin pigments, which can be preserved for millions of years in fossilized soft tissues. The shape, size, and arrangement of these melanosomes correlate with specific colors in modern animals, allowing researchers to infer the original coloration of extinct species. Studies of the feathered dinosaur Microraptor revealed it likely had iridescent black plumage similar to modern crows. Another small dinosaur, Sinosauropteryx, appears to have had a reddish-brown back and a banded tail. Even more remarkably, a study of the ceratopsian Psittacosaurus identified skin coloration showing countershading—darker on top and lighter underneath—a common camouflage pattern in modern animals. These discoveries are transforming dinosaur depictions from speculative to scientifically accurate representations based on direct evidence.

Skin Impressions from Titanosaurs and Other Sauropods

While feathered dinosaur discoveries have captured much public attention, equally important are fossils preserving the skin impressions of sauropods—the largest land animals ever to walk the Earth. Unlike their theropod relatives, sauropods appear to have retained scales throughout their evolutionary history. Remarkable skin impressions from titanosaurs found in Argentina reveal a distinctive pattern of small, non-overlapping scales with larger feature scales arranged in rosette patterns. A particularly important discovery was made in Spain, where hundreds of titanosaur skin impressions were found alongside a nesting site, showing variations in scale patterns between different body regions. These fossils refute earlier speculation that sauropods might have had feathery coverings like some other dinosaur groups. Instead, their skin more closely resembled that of modern reptiles, though arranged in distinctive patterns unique to sauropods. Interestingly, the small, non-overlapping scales might have helped these massive animals regulate their body temperature, as the channels between scales could have facilitated blood flow near the skin surface for cooling.

Techniques for Studying Fossil Impressions

Studying delicate skin and feather impressions requires specialized techniques far beyond those used for traditional bone fossils. Paleontologists often employ low-angle lighting to enhance the subtle topography of skin impressions that might be nearly invisible under direct light. Silicone peels—where liquid silicone is applied to a fossil and allowed to set—can create detailed casts that reveal features difficult to see in the original. For microscopic analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) allows researchers to examine the cellular structure of preserved soft tissues at magnifications thousands of times greater than possible with optical microscopes. More recently, synchrotron radiation techniques, which use highly focused X-rays generated by particle accelerators, have revealed chemical signatures of original organic compounds still present in some exceptionally preserved fossils. These advanced methods have enabled researchers to identify melanosomes, keratin structures, and other cellular components in fossil impressions. Modern photogrammetry and 3D scanning have also revolutionized the field, allowing the creation of high-resolution digital models that can be shared globally among researchers.

Skin Impressions from Ornithischian Dinosaurs

Ornithischian dinosaurs—including hadrosaurs, ceratopsians, stegosaurs, and ankylosaurs—have yielded some of the most extensive skin impressions in the fossil record. The “mummy” specimens of duck-billed dinosaurs from North America preserve skin across large portions of the body, revealing a complex covering of scales that varied by body region. Hadrosaurs typically had small, polygonal scales covering most of the body, with larger, feature scales arranged in rows or clusters in specific areas. The remarkable Psittacosaurus specimen from China preserves not only scales but also a series of stiff bristle-like structures along its tail that may have served a display function. Ankylosaurs, with their heavily armored bodies, show impressions of the bases of their bony armor plates as well as the smaller scales covering the skin between them. A particularly important specimen of the ankylosaur Borealopelta from Alberta, Canada, preserves skin so well that researchers could identify a reddish-brown coloration on its upper surfaces, suggesting even these heavily armored dinosaurs relied partly on camouflage for protection from predators.

Evidence of Dinosaur Display Structures

Fossil impressions have revealed that many dinosaurs possessed specialized skin structures likely used for display, communication, or species recognition. The most dramatic examples come from theropod dinosaurs like Caudipteryx and Microraptor, which had long display feathers on their tails and limbs that would have been useless for flight but striking in appearance. Evidence also exists for display structures in non-feathered dinosaurs. Fossil skin impressions of certain hadrosaurs show elaborate crests of modified scales that might have been brightly colored in life. The discovery of a well-preserved specimen of Psittacosaurus revealed a previously unknown fan-like structure on its tail composed of bristle-like projections that likely served a display function. Ceratopsian fossils occasionally preserve impressions of skin flaps or frills that extended the bony structures of their skulls, potentially creating even more impressive visual displays than the skeleton alone would suggest. These findings indicate that dinosaurs, like modern birds and reptiles, likely engaged in complex visual communication using both permanent anatomical features and seasonal display structures.

Reconstructing Dinosaur Appearance: Art Meets Science

Creating accurate reconstructions of dinosaur appearance has evolved from artistic speculation to science-based visualization through the study of fossil impressions. Modern paleoartists work closely with paleontologists, using evidence from skin and feather impressions to create scientifically rigorous depictions. This process typically begins with a skeletal reconstruction based on fossil bones, which provides the framework for body shape and proportions. Information from skin impressions is then mapped onto this skeleton, showing the texture and patterns of scales or feathers in different body regions. When coloration evidence exists, as with melanosomes in some feathered dinosaurs, this information is incorporated as well. For areas where direct evidence is lacking, artists apply the principle of phylogenetic bracketing—inferring likely features based on those present in closely related species. The resulting reconstructions undergo scientific peer review before being presented to the public. Over recent decades, this methodology has transformed dinosaur depictions from the drab, lizard-like creatures of early 20th-century reconstructions to today’s more vibrant, dynamic, and often feathered representations that reflect our current scientific understanding.

Future Frontiers in Dinosaur Soft Tissue Research

The field of dinosaur soft tissue research continues to advance rapidly, with new technologies offering opportunities to extract even more information from fossil impressions. Developments in chemical analysis allow researchers to identify traces of original organic molecules that may still be present in exceptionally preserved fossils. Portable X-ray fluorescence devices can now detect chemical signatures of soft tissues directly in the field, potentially revealing impressions not visible to the naked eye. Machine learning algorithms are being developed to analyze patterns in fossil impressions and compare them with skin and feather patterns in modern animals, potentially identifying biological features not previously recognized. Perhaps most exciting is the emerging field of paleoproteomics, which aims to extract and sequence ancient proteins from fossils—proteins being more durable than DNA and potentially recoverable from much older specimens. These advances suggest that future research may reveal not just what dinosaurs looked like on the outside, but also details of their physiology, metabolism, and even genetic makeup, continuing to refine our understanding of these fascinating extinct animals.

Conclusion: Reimagining Dinosaurs Through Their Skin

The study of fossil impressions has fundamentally transformed our understanding of dinosaurs from mere skeletons to living, breathing animals with complex external coverings. Through these rare windows into the past, we’ve learned that dinosaurs weren’t simply scaly reptiles but displayed a remarkable diversity of external coverings—from the complex scale patterns of hadrosaurs to the feathered coats of many theropods. We now know that many dinosaurs were colorful, with patterns serving functions from camouflage to display. Perhaps most importantly, skin and feather impressions have cemented the evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and birds, demonstrating that feathers evolved millions of years before the first bird took flight. As new specimens are discovered and new technologies are developed to analyze them, our picture of dinosaur appearance continues to be refined. Each fossil impression brings us closer to understanding these remarkable animals not as monsters from a prehistoric past, but as real creatures that once walked the Earth—diverse, dynamic, and far more bird-like than early paleontologists ever imagined.