The roars we hear in Jurassic Park are pure Hollywood fiction. Those terrifying came from recordings of elephant bellows, lion roars, and even somebody’s pet dog. Yet the question remains tantalizingly mysterious: what did these magnificent creatures actually sound like millions of years ago?

Scientists today are tackling this challenge using cutting-edge technology, fossil evidence, and computational modeling. They’re turning silent fossils into sound generators, breathing acoustic life back into creatures that vanished eons ago.

The Digital Reconstruction Revolution

Scientists at Sandia National Laboratories pioneered the digital approach by creating three-dimensional computer models of fossilized dinosaur crests using CT scans, taking about 350 cross sections of skulls at 3mm intervals. Once the size and shape of air passages were determined with powerful computers and unique software, it became possible to determine the natural frequency of sound waves the dinosaur pumped out, much the same as the size and shape of a musical instrument governs its pitch and tone.

This breakthrough happened with Parasaurolophus, a duck-billed dinosaur whose bony crest had puzzled scientists for decades. The cross sections were loaded in numerical form into a computer to reconstruct an undistorted crest, with scientists studying the images and instructing the computer how to read density to sort out which was bone and which was sandstone and clay that filled the fossil.

Physical Modeling with Modern Materials

To understand the acoustic properties of dinosaur crests, researchers created physical models that mirrored fossil structures, consisting of tubes arranged to resemble the hollow chambers within actual crests. The model was delicately suspended by cotton threads, with a small speaker used to introduce sound vibrations and a microphone positioned to capture resulting frequencies.

These experiments represent a hands-on approach to paleoacoustics. Such physical models highlighting that while it isn’t an exact replica of the Parasaurolophus crest, it provides something simplified and accessible for both modeling and building a physical device.

Discovering Ancient Voice Boxes

In the mid-1990s, Vegavis iaai, an ancient bird dating to around 66 to 68 million years ago, was excavated in Antarctica, and Dr. Julia Clarke later found evidence that Vegavis had a vocal organ specific to birds, known as a syrinx. The organ is made of calcified cartilage like shark skeletons and rarely becomes fossilized, which is why most shark fossils are actually teeth and why the oldest syrinx previously found was only a couple million years old.

The discovery wasn’t immediate. During subsequent analysis, further analysis of CT scan images revealed something new – a tiny structure that looked like a simple bone fragment on the rock surface, which turned out to be the syrinx. Comparison with syrinxes of 12 modern birds suggested Vegavis has a syrinx most closely related to those of ducks and geese, and judging from how specialized it looked, the organ evolved relatively late in their evolutionary line.

Computational Sound Simulation

Computer scientists and paleontologists produced low-frequency sounds using computed tomography (CT) scans and powerful computers, with the dinosaur apparently emitting a resonating low-frequency rumbling sound that can change in pitch. “It’s only recently that computers have become powerful enough to allow that to happen,” with the computer then instructed to simulate air blowing through the crest, resulting in sound that probably approximates the noises the dinosaur crest could produce fairly well.

High-performance computers were used for initial image processing, analysis and actual sound creation, including Compaq Computer professional workstations, Intergraph Corporation TDZ workstations, and Silicon Graphics infinite reality workstations, using the same computer-modeling techniques Sandia uses to create complex three-dimensional models for conducting simulations of problems that cannot be subjected to real-world tests.

Closed-Mouth Vocalizations Theory

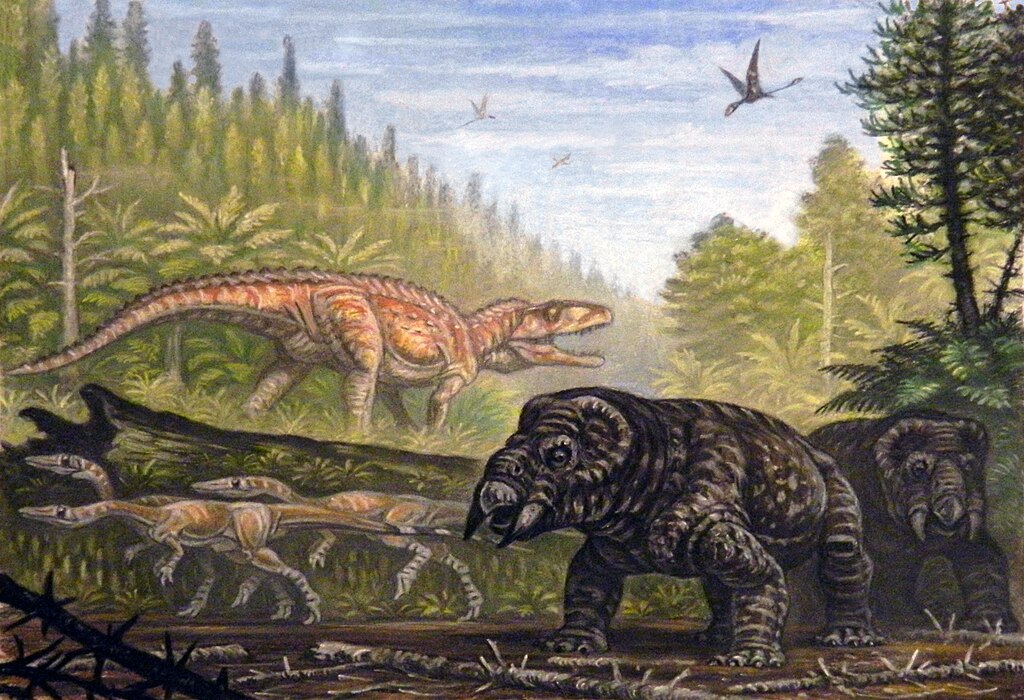

Scientists theorize that many dinosaurs may have produced closed-mouth vocalizations by inflating their esophagus or tracheal pouches while keeping their mouth closed, producing something comparable to a low-pitched swooshing, growling, or cooing sound. These closed-mouth vocalizations are lower and more percussive, as opposed to bird calls which are more varied in pitch and almost melodic, with modern examples including crocodilian growls and ostrich booms.

This challenges Hollywood depictions completely. The exciting, blood-curdling roars in the Jurassic Park franchise are not scientifically accurate, with current evidence supporting that Tyrannosaurus rex made closed-mouth vocalizations, but in the films, the Tyrannosaurus opens its mouth every time it roars.

Rare Fossilized Voice Box Discoveries

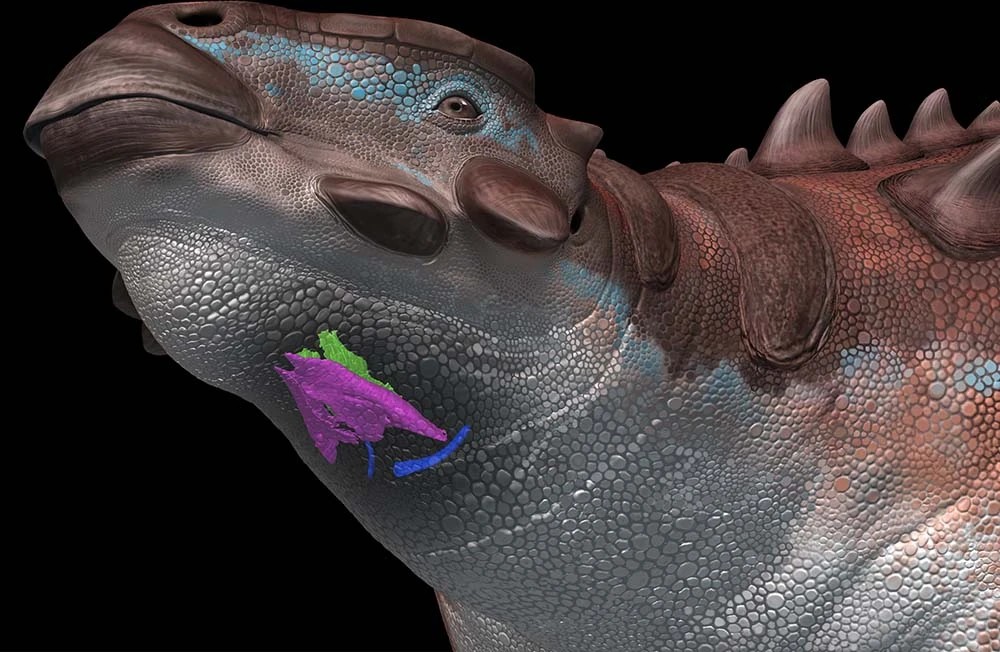

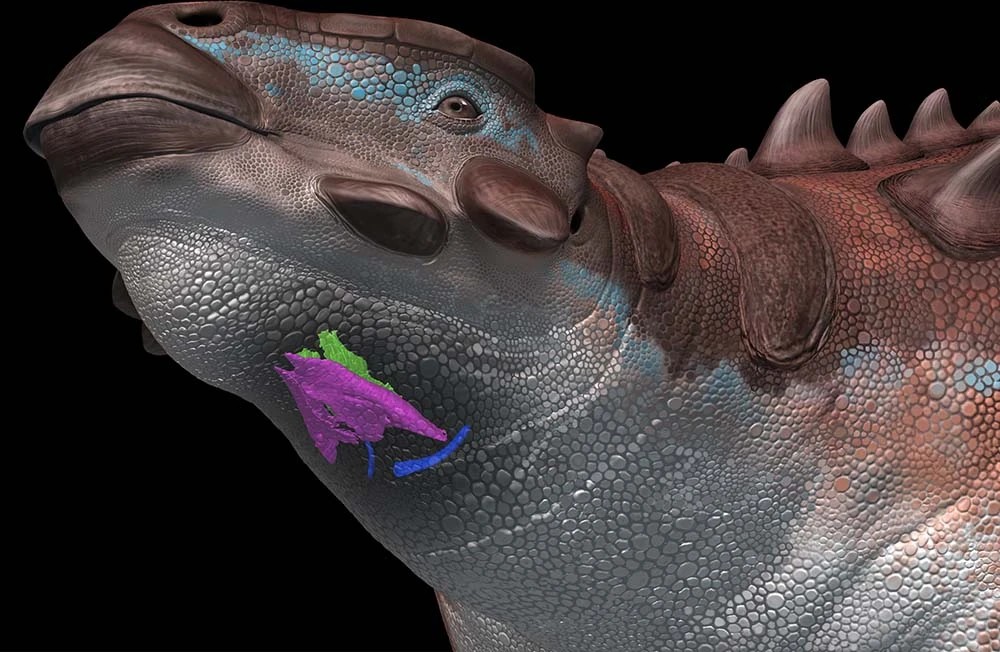

Research on Pinacosaurus grangeri, a squat, armor-plated and club-tailed ankylosaur from Mongolia, represents the first fossilized voice box found in a non-avian dinosaur. Researchers studied two parts of the fossilized larynx that would have worked with muscles to elongate the airway and alter its shape, finding that P. grangeri had a very large cricoid and two long bones used to adjust its size – a layout that turned the voice box into a vocal modifier.

Ancient voice box specimens like this are extremely rare, as these respiratory tissues don’t normally survive to make it into the fossil record, yet against the odds, the larynx of this ankylosaur has remained preserved since around 84-72 million years ago.

Evolutionary Implications and Future Research

Dinosaurs fossils are the most studied out of all fossils with literally millions in collections all over the planet, but not one single syrinx has been found in nonavian dinosaurs – either scientists have missed some, or dinosaurs never had them which means they didn’t make honking noises. The apparent absence of syrinxes in nonavian dinosaur fossils of the same age indicates that the organ may have originated late in the evolution of birds and that other dinosaurs may not have been able to make noises similar to the bird calls we hear today.

As research progresses, scientists hope to unravel whether these sounds were unique to each species, locality, or even individual, with the broader implications of paleoacoustic research being vast as scientists can apply these methods to other prehistoric animals, providing a comprehensive soundtrack of the past. This specimen helps us better understand the evolutionary history of dinosaur vocal anatomy but also opens up new questions about whether paleontologists have overlooked similar laryngeal structures in other early dinosaurs, and whether the syrinx evolved earlier than thought.

The quest to reveals how science can transform silent stones into symphonies from the past. Through digital reconstruction, physical modeling, and rare fossil discoveries, researchers are slowly piecing together the acoustic landscape of prehistoric Earth. While we may never hear the exact sounds that echoed through Mesozoic forests, these scientific endeavors bring us tantalizingly close to experiencing what it might have sounded like when giants walked the Earth. What sounds do you think would have surprised you most in the age of dinosaurs?