The Ice Age conjures images of massive woolly mammoths trudging across tundra, but perhaps no prehistoric predator captures our imagination quite like the saber-toothed tiger. With its iconic elongated canines and powerful build, this magnificent hunter dominated Pleistocene landscapes for over two million years. Though commonly called a “tiger,” Smilodon (its scientific name) wasn’t related to modern tigers at all, representing instead a separate, now-extinct cat lineage that evolved specialized adaptations for hunting the megafauna of its era. From North to South America, these remarkable predators ruled their domains with evolutionary innovations that made them perfectly suited to thrive during one of Earth’s most challenging climatic periods. Let’s explore how these fascinating prehistoric cats came to dominate their world.

The Evolutionary Rise of Saber-Toothed Cats

Contrary to popular belief, saber-toothed cats weren’t a single species but rather a diverse group that evolved multiple times throughout mammalian history. The most famous genus, Smilodon, appeared approximately 2.5 million years ago during the Pleistocene epoch, but the saber-tooth adaptation emerged independently in several carnivorous lineages through convergent evolution. Paleontologists have identified at least three distinct families that developed elongated canines, including the nimravids (false saber-tooths), machairodontines (true saber-toothed cats), and the marsupial thylacosmilids of South America. This repeated evolution of similar dental adaptations across unrelated groups suggests that the saber-tooth design represented a highly effective hunting strategy for large-bodied predators. Smilodon itself evolved from earlier machairodontine ancestors, gradually developing more pronounced canines and more robust limbs as it specialized for hunting the large herbivores that dominated Ice Age landscapes.

Smilodon: The Most Iconic Saber-Tooth

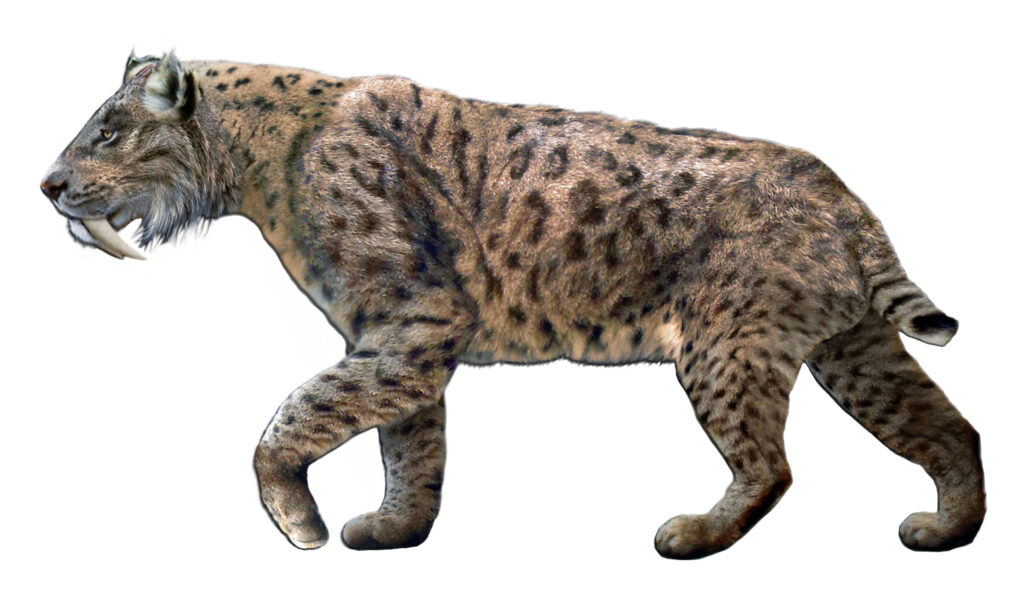

Of all saber-toothed cats, Smilodon fatalis and its larger relative Smilodon populator stand as the quintessential representations of these prehistoric predators. Smilodon fatalis roamed across North and Central America, while the imposing Smilodon populator inhabited South America and may have been the largest cat that ever lived, potentially reaching weights of up to 880 pounds. Unlike modern big cats with their sleek, agile builds, Smilodon possessed a remarkably robust physique with powerful forelimbs, a relatively short tail, and a muscular neck. Their skull structure differed significantly from modern felines, featuring a wider jaw gape that could open to nearly 120 degrees—an adaptation necessary to accommodate those impressive canines. The canine teeth themselves were flattened, curved, and serrated along the edges, more resembling knives than the conical teeth of modern cats. These distinctive features made Smilodon instantly recognizable and established it as the dominant predator across much of the Americas during the Late Pleistocene.

The Truth Behind the Iconic Teeth

The trademark feature of saber-toothed cats—their elongated caninehasve been the subject of extensive scientific research and debate. These impressive teeth could reach up to 7 inches in length in Smilodon populator, making them truly formidable weapons. Contrary to early assumptions, these teeth were remarkably strong despite their apparent fragility, composed of dentin surrounded by enamel that was thicker on the outer surface but thinner on the inside. This structure created a self-sharpening effect as the teeth wore down through use. The canines weren’t designed for crushing bone like those of modern lions and tigers; instead, they functioned more like surgical instruments, capable of slicing through soft tissue with minimal force. Microscopic wear patterns on fossilized teeth suggest they rarely contacted bone during hunting, indicating a highly specialized killing technique. Rather than being merely for display or intimidation, these elongated canines represented a sophisticated evolutionary adaptation that allowed Smilodon to efficiently dispatch large prey with minimal risk of injury to the predator itself.

Hunting Strategies of the Ice Age’s Top Predator

Smilodon employed hunting tactics vastly different from those of modern big cats, dictated by its unique physical attributes. Unlike the high-speed pursuits of cheetahs or the stalking approaches of lions and tigers, Smilodon was built for ambush and overwhelming power rather than sustained chases. Its stocky, muscular build with relatively shorter legs indicates it likely relied on surprise attacks, bursting from concealment to tackle large prey. Once the prey was subdued, Smilodon’s incredibly powerful forelimbs—approximately twice as strong as those of modern lions—would have held the struggling animal in place. The killing method likely involved a precisely targeted bite to the throat or belly using those specialized canines, severing major blood vessels and causing rapid blood loss. This hunting strategy allowed Smilodon to effectively target megafauna like giant ground sloths, young mammoths, and bison, prey animals sometimes several times its weight. Interestingly, recent biomechanical analyses suggest that Smilodon’s bite force was weaker than that of similar-sized modern cats, further indicating it relied on specialized killing techniques rather than crushing power.

Physical Adaptations Beyond the Teeth

While Smilodon’s impressive canines often dominate discussions, this predator possessed numerous other physical adaptations that contributed to its success. The cat’s exceptionally muscular neck featured elongated neural spines on the vertebrae, providing attachment points for powerful muscles that could both protect the canines from breakage and deliver devastating downward force during a kill. Its broad shoulder blades and robust forelimbs featured large attachment sites for muscles that granted tremendous grappling strength, allowing it to wrestle prey much larger than itself to the ground. Unlike modern cats with their flexible spines optimized for running, Smilodon had a stiffer, more bear-like back that provided stability and power during close-quarters combat with large prey. The hind limbs, while strong, were proportionally shorter than those of modern big cats, further indicating Smilodon was not built for sustained pursuit. Even its paws were specialized, with retractable claws that were larger and more curved than those of modern cats, providing superior grappling ability when subduing struggling prey.

Social Structure: Lone Hunters or Pack Predators?

The social behavior of Smilodon remains one of the most intriguing aspects of its biology, with evidence increasingly suggesting these cats may have lived in social groups similar to modern lions. The La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles have yielded hundreds of Smilodon specimens, with population demographics showing a relatively high number of healed injuries that would have temporarily disabled these predators. Such injuries would likely have proven fatal to solitary hunters unable to feed themselves while recovering, suggesting these cats may have benefited from group living and possibly cooperative hunting. Additional evidence comes from the relatively low degree of sexual dimorphism in Smilodon compared to solitary modern cats like tigers—a trait more consistent with group-living species. The ability to tackle extremely large prey would have been enhanced through cooperative hunting, as multiple Smilodons could more effectively subdue dangerous herbivores like giant bison or young mammoths. If Smilodon did indeed hunt in groups, this social structure would have represented a significant advantage in the competitive Ice Age ecosystem, allowing them to dominate as apex predators across their range.

The Perfect Predator for Megafauna

The Pleistocene epoch was characterized by an abundance of large mammalian species—collectively known as megafauna—that provided the perfect ecological niche for specialized predators like Smilodon. The Ice Age landscape sustained enormous herbivores, including woolly mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, and prehistoric bison that dwarfed their modern counterparts. Smilodon evolved specifically to exploit this abundance of large prey, with its unique combination of powerful build and specialized dentition allowing it to efficiently dispatch animals many times its size. Unlike modern big cats that often target prey smaller than themselves, Smilodon regularly hunted megaherbivores that could weigh several tons. Their saber teeth were particularly effective against the thick hides of these large mammals, capable of delivering precise, fatal wounds to vulnerable areas. This specialization made Smilodon extraordinarily successful during the Pleistocene but ultimately contributed to its vulnerability when the megafauna began to disappear. In essence, Smilodon represented a pinnacle of evolutionary specialization, perfectly adapted for the unique ecological conditions of the Ice Age.

Geographic Distribution and Species Diversity

The Smilodon genus achieved remarkable success across the Americas, evolving into three distinct species with different geographic ranges and physical characteristics. The earliest species, Smilodon gracilis, appeared around 2.5 million years ago in North America and was the smallest of the three, weighing approximately 200-300 pounds. This species eventually gave rise to Smilodon fatalis, which spread throughout North and Central America and parts of northwestern South America, reaching weights of 350-600 pounds. The most impressive species, Smilodon populator, evolved in South America and became the largest, with some individuals potentially reaching nearly 900 pounds. Their combined range extended from what is now Alaska to Patagonia at the southern tip of South America, demonstrating the remarkable adaptability of these predators across diverse habitats, including grasslands, open woodlands, and even semi-arid regions. This wide distribution allowed Smilodon to interact with numerous prey species and coexist with other large predators, including dire wolves, American lions, and the enormous short-faced bear, creating complex predator-prey dynamics across two continents.

Competitors in the Pleistocene Landscape

Despite its formidable hunting prowess, Smilodon didn’t rule the Ice Age unopposed. These specialized cats shared their territory with numerous other apex predators, creating intense competition for resources. In North America, Smilodon fatalis competed directly with the American lion (Panthera atrox), a cat even larger than modern African lions that likely targeted similar prey. Dire wolves (Canis dirus) hunted in packs and, while smaller individually than Smilodon, could potentially overwhelm a saber-tooth through numbers. The short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), standing up to 12 feet tall on its hind legs, represented perhaps the most intimidating competitor, capable of stealing Smilodon kills through sheer size advantage. Evidence from the La Brea Tar Pits suggests fierce competition occurred regularly, with multiple predator species sometimes trapped while attempting to feed on the same carcass. This competitive pressure likely drove further specialization in Smilodon’s hunting techniques, pushing it toward a niche that capitalized on its unique physical attributes to target specific prey in ways other predators couldn’t match.

The Science Behind Saber-Tooth Fossils

Our extensive knowledge of Smilodon comes primarily from an exceptionally rich fossil record, with the La Brea Tar Pits providing the most comprehensive collection of specimens anywhere in the world. These natural asphalt seeps in what is now Los Angeles, California, acted as perfect preservation traps over tens of thousands of years, capturing animals that became stuck while attempting to drink or feed on already-trapped prey. More than 2,000 Smilodon individuals have been recovered from La Brea alone, allowing scientists to analyze population demographics, study pathologies and injuries, and even extract ancient DNA fragments. Modern technological advances have revolutionized how researchers study these fossils, with CT scanning revealing internal structures of bones and teeth, isotope analysis determining dietary patterns, and digital biomechanical modeling testing hypotheses about hunting behavior. Microscopic examination of tooth wear patterns provides insights into feeding habits, while careful study of muscle attachment points on bones allows reasonable reconstruction of soft tissues. These scientific approaches have transformed Smilodon from a mysterious Ice Age monster into one of the most thoroughly understood extinct predators, providing a detailed picture of how these remarkable cats dominated their prehistoric world.

Climate Adaptation During the Ice Age

The Pleistocene epoch was characterized by dramatic climate fluctuations, with multiple glacial periods (ice ages) interspersed with warmer interglacial phases. Smilodon’s long evolutionary history spanning over two million years demonstrates remarkable adaptability to these changing conditions. Unlike the popular image of ice ages as uniformly frozen landscapes, the environments Smilodon inhabited varied considerably, including grasslands, savannas, open woodlands, and even semi-tropical regions during warmer periods. Evidence suggests Smilodon likely possessed a coat adapted to cooler temperatures, particularly in northern populations, though probably not as shaggy as ice age mammals like woolly mammoths. Their robust build would have provided favorable surface-area-to-volume ratios for heat conservation in colder climates. Perhaps most importantly, Smilodon’s specialization for hunting large herbivores served it well during climate shifts, as these prey animals represented walking reservoirs of calories and moisture that could sustain the predator through challenging seasonal conditions. This adaptability to climate variability allowed Smilodon to persist through multiple glacial-interglacial cycles, making it one of the most successful large predators of the Pleistocene.

The Mystery of Extinction

After thriving for over two million years, Smilodon disappeared relatively suddenly around 10,000 years ago, coinciding with the end of the last ice age and the arrival of humans throughout the Americas. This timing has fueled scientific debate about the causes of extinction, with two main theories predominating. The first proposes that climate change at the end of the Pleistocene altered habitats and reduced prey availability, particularly impacting specialized predators like Smilodon that depended on megafauna. The second theory implicates human hunting—the “overkill hypothesis”—suggesting that newly arrived human hunters efficiently targeted the same large herbivores Smilodon depended upon, effectively removing their food source. Most paleontologists now favor a combination of these factors, proposing that climate change stressed megafaunal populations that were then pushed to extinction by human hunting pressure. Smilodon, as a specialized predator of large mammals, would have been particularly vulnerable to this one-two punch. Unlike more adaptable carnivores such as wolves and pumas that survived this extinction event, Smilodon’s specialized hunting adaptations that had served it so well during the Ice Age proved disadvantageous when its preferred prey disappeared.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Though extinct for 10,000 years, the saber-toothed cat maintains a powerful presence in human culture and continues to influence our understanding of prehistoric predators. As one of the most recognizable Ice Age mammals, Smilodon appears frequently in museum exhibitions, nature documentaries, and popular media, often symbolizing the wild danger of prehistoric times. The La Brea Tar Pits museum in Los Angeles features Smilodon fatalis as its mascot, celebrating this predator’s significant presence in the local fossil record. California even designated Smilodon californicus (now classified as S. fatalis) as its official state fossil in 1973. Beyond public fascination, ongoing scientific research on Smilodon continues to provide valuable insights into evolutionary processes, predator-prey relationships, and extinction dynamics. Studies of its specialized adaptations help biologists understand how predators evolve in response to their environments and prey, while its ultimate extinction offers sobering lessons about the vulnerability of even the most successful specialized species to rapid environmental change. In this way, the saber-toothed cat remains a powerful icon of both evolutionary success and the transient nature of dominance in the natural world.

Conclusion

The saber-toothed tiger stands as one of nature’s most remarkable evolutionary experiments—a specialized predator perfectly designed for the unique conditions of the Pleistocene epoch. For over two million years, these magnificent cats ruled as apex predators across the Americas, their distinctive canines and powerful builds representing the pinnacle of carnivore specialization for taking down Ice Age megafauna. Though they eventually succumbed to the combined pressures of climate change and human arrival, their long reign testifies to the remarkable success of their evolutionary adaptations. The story of Smilodon reminds us that evolution produces not only generalists capable of surviving changing conditions but also specialists so perfectly adapted to their ecological niches that they temporarily dominate entire ecosystems. As we continue studying these magnificent prehistoric predators, they offer valuable insights into evolutionary processes, extinction dynamics, and the delicate balance of predator-prey relationships that shape our natural world.