Picture yourself floating through crystal-clear waters two hundred million years ago. The sun filters down through waves, illuminating a world completely different from today’s oceans. You’re witnessing what scientists now call the Jurassic aquarium – an underwater realm where massive marine reptiles rule the seas, enormous spiral shells drift like living submarines, and razor-toothed predators patrol ancient coral reefs.

While most people think of dinosaurs when they hear “Jurassic,” the real action during this period was happening beneath the waves. When dinosaurs ruled the land, the oceans teemed with equally fascinating and fearsome creatures. These prehistoric seas were packed with life forms so extraordinary that they make today’s marine animals look ordinary by comparison.

The Ocean Giants: Plesiosaurs and Their Legendary Necks

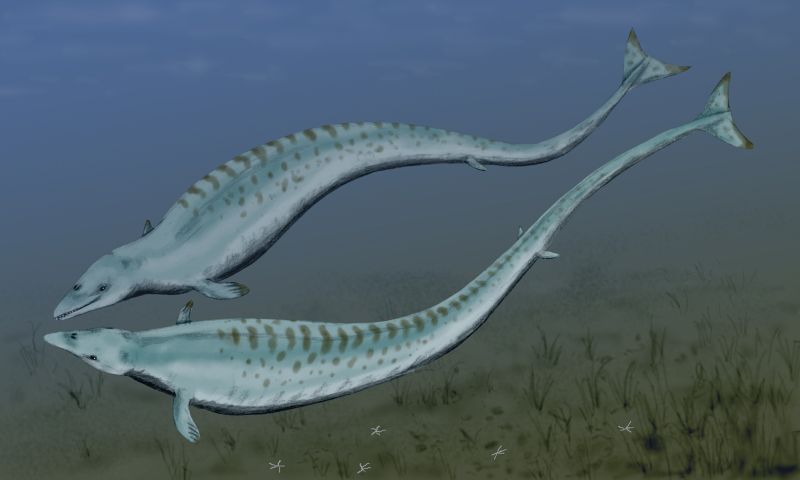

Long before whales dominated the seas, plesiosaurs were the undisputed rulers of Jurassic waters. These weren’t dinosaurs – they were marine reptiles that had evolved specifically for life in the ocean. Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period, possibly in the Rhaetian stage, about 203 million years ago. They became especially common during the Jurassic Period, thriving until their disappearance due to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 66 million years ago.

What made these creatures so remarkable was their incredible diversity in size and shape. Plesiosaurus is one of my favorite prehistoric creatures. They were massive with long necks that made up half the length of their bodies. They grew up to 43 feet, about the size of a very large bus, but their size didn’t stop them from flying through the water. Can you imagine encountering one of these gentle giants gliding through the warm Jurassic seas, their impossibly long necks swaying like underwater serpents?

The discovery of plesiosaurs has one of the most inspiring stories in paleontology. The Plesiosaurus was discovered in 1823 by Mary Anning, also known as the mother of paleontology. She was ahead of her time, documenting fossils before the word “dinosaur” was even around, it wouldn’t be coined until 1842. She would search for fossils along the coasts near her home with her trusty dog Tray. She found her first ichthyosaur when she was just 12!

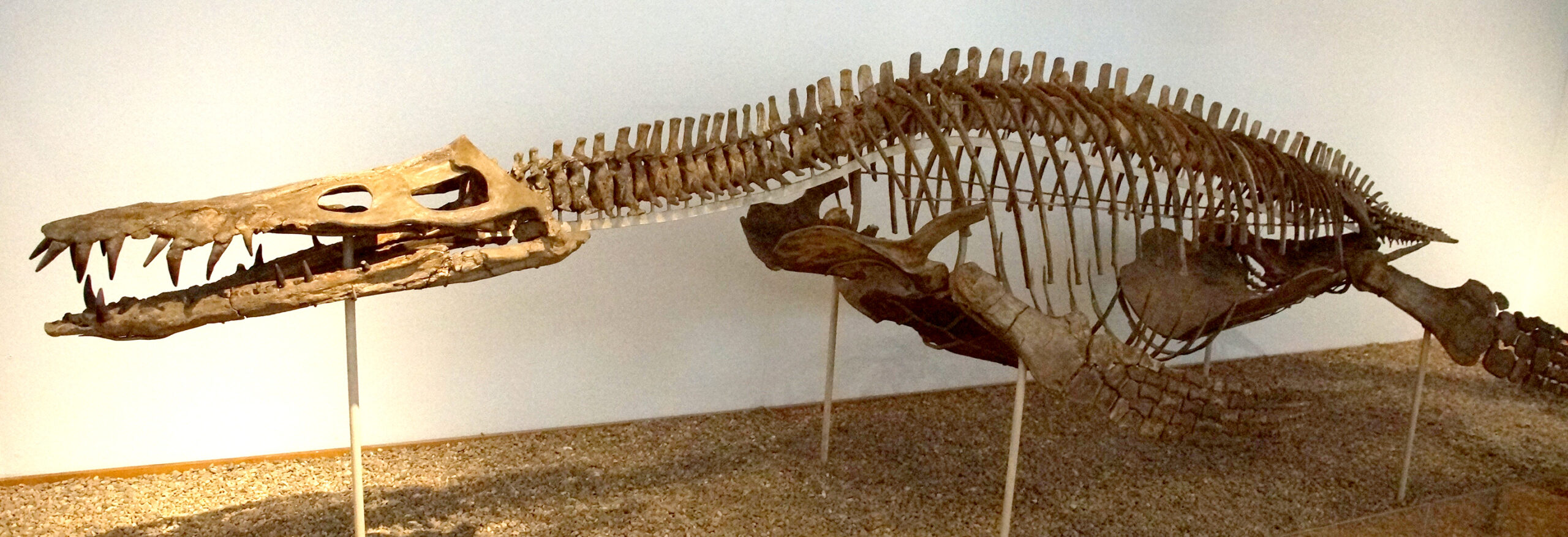

Dolphin Mimics: The Streamlined Ichthyosaurs

If plesiosaurs were the gentle giants, ichthyosaurs were the speed demons of the Jurassic seas. These remarkable marine reptiles evolved to look almost exactly like modern dolphins – a perfect example of how similar environments create similar body shapes across millions of years. During the Early Triassic epoch, ichthyosaurs and other ichthyosauromorphs evolved from a group of unidentified land reptiles that returned to the sea, in a development similar to how the mammalian land-dwelling ancestors of modern-day dolphins and whales returned to the sea millions of years later, which they gradually came to resemble in a case of convergent evolution.

These weren’t just any ordinary marine reptiles – they were built for speed and deep diving. Ichthyosaurs had sleek profiles similar to those of modern fast-swimming fish and had large eye orbits, perhaps the largest of any vertebrate ever. Think about that for a moment – the largest eyes of any vertebrate that ever lived! Temnodontosaurus, with eyes that had a diameter of twenty-five centimetres, could probably still see at a depth of 1,600 metres.

Some ichthyosaurs reached absolutely mind-boggling sizes. The gigantic Shonisaurus sikanniensis (considered as a shastasaurus between 2011 and 2013) whose remains were found in the Pardonet Formation of British Columbia, has been estimated to be as much as 21 m (69 ft) in length. Ichthyotitan, found in Somerset, has been estimated to be as much as 26 m long – if correct, the largest marine reptile known to date. These were essentially whale-sized predators with the agility of dolphins!

Apex Predators: The Terrifying Pliosaurs

While their long-necked cousins were graceful filter-feeders, pliosaurs were the T. rex of the sea – massive, powerful, and absolutely terrifying. Pliosaur, a group of large carnivorous marine reptiles characterized by massive heads, short necks, and streamlined tear-shaped bodies. Pliosaurs possessed powerful jaws and large teeth, and they used four large fins to swim through Mesozoic seas.

The most famous of these sea monsters was Liopleurodon, a name that strikes fear into the hearts of anyone who’s ever watched a dinosaur documentary. Reaching 6 m and perhaps twice this, Liopleurodon has a giant, long-snouted skull lined with deeply rooted, conical teeth. It was undoubtedly a powerful predator of other vertebrates, presumably grabbing and dismembering other plesiosaurs as well as ichthyosaurs, crocodyliforms and fish.

But Liopleurodon wasn’t even the biggest pliosaur. Some thalassophonean pliosaurs, such as some species of Pliosaurus, had skulls up to two metres in length with body lengths estimated around 10–12 meters (33–39 ft), making them the apex predators of Late Jurassic oceans. Picture a skull two meters long – that’s taller than most people! These were the ultimate marine predators, capable of taking down almost anything that swam in their domain.

Living Submarines: The Mysterious Ammonites

Among the most abundant and beautiful creatures of the Jurassic seas were the ammonites – cephalopods with coiled shells that functioned like natural submarines. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family Nautilidae). The earliest ammonoids appeared during the Emsian stage of the Early Devonian (410.62 million years ago), with the last species vanishing during or soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (66 million years ago).

These weren’t just pretty shells – they were sophisticated creatures with remarkable engineering. The ammonite itself lived in only the last chamber, the body-chamber; earlier chambers were filled with gas or fluid, which the ammonite was able to regulate in order to control its buoyancy and movement, much like a submarine. The variety in size was staggering. Ammonites show an enormous range in size, from the very small to the height of a human. For example, the Late Jurassic Nannocardioceras is very small; complete adults are rarely more than 20 mm in diameter. Parapuzosia seppenradensis, from the Late Cretaceous, is 1.95 m in diameter. If complete, this specimen would have had a diameter of about 2.55 m.

What’s fascinating is how they lived and fed. Though it would largely have depended on their size, ammonites would likely have eaten similar things to today’s cephalopods, such as crustaceans, bivalves and fish. Smaller species would probably have eaten plankton. They weren’t just passive drifters – they were active participants in the marine ecosystem, both as predators and prey.

The Bullet-Shaped Hunters: Belemnites

If ammonites were the submarines of the Jurassic, belemnites were the torpedoes. Belemnites were marine animals belonging to the phylum Mollusca and the class Cephalopoda. Their closest living relatives are squid and cuttlefish.They h ad a squid-like body but, unlike modern squid, they had a hard internal skeleton. This internal skeleton, called a rostrum, is what we usually find as fossils – bullet-shaped structures that once helped these creatures maintain balance while swimming.

The size range of belemnites was impressive, though nowhere near as extreme as their ammonite cousins. The largest belemnite rostrum known comes from Indonesia. It is about 46 cm long; the animal itself must have been 4-5 m long. Neohibolites minimus has a rostrum only about three centimetres long. These creatures were incredibly important to the marine ecosystem. Belemnites were an important food source for many Mesozoic marine creatures, both the adults and the planktonic juveniles and they likely played an important role in restructuring marine ecosystems after the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event.

The Gentle Filter-Feeders: Leedsichthys

Not everything in the Jurassic seas was a fearsome predator. Leedsichthys, meaning “Leeds’ fish,” is considered the biggest ray-finned fish. It roamed the Jurassic seas, potentially reaching 27 meters (88.5 ft) in length. This prehistoric sea creature was a gentle filter feeder. Similar to a modern Blue Whale, Leedsichthys sieved plankton from the water with its 40,000 teeth.

Imagine encountering this massive fish – longer than most whales today – peacefully swimming along with its mouth wide open, filtering countless tiny organisms from the water. Despite its colossal size, Leedsichthys wasn’t invincible to predators like Liopleurodon and Metriorhynchus. In addition, the annual shedding of its filter plates left it vulnerable for weeks. Interestingly, Leedsichthys holds the title of the earliest identified giant filter-feeding marine animal, showcasing a unique evolutionary path during the plankton-rich Jurassic period.

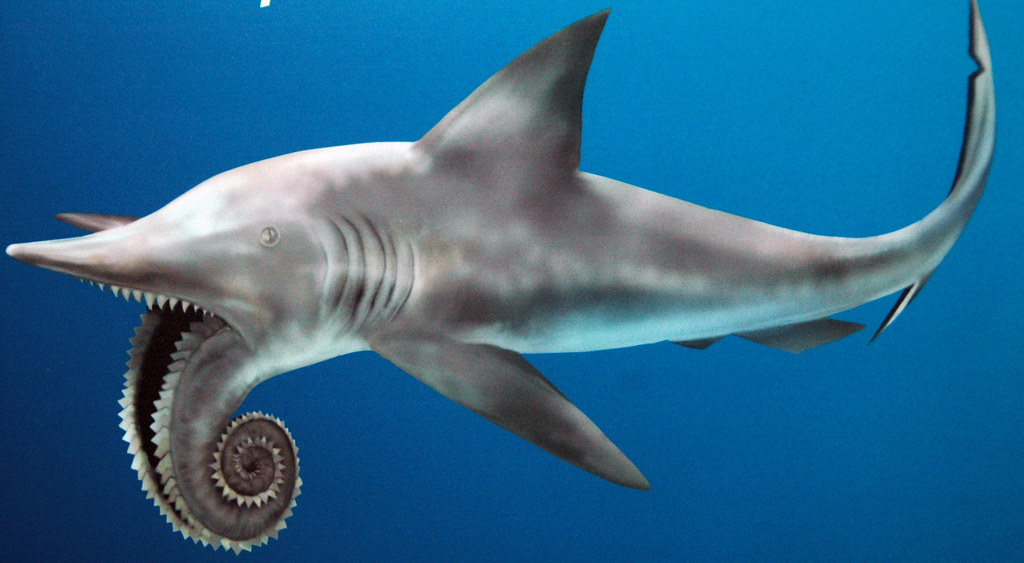

Prehistoric Sharks and Ancient Terror

The Jurassic seas weren’t just home to marine reptiles and cephalopods – they also hosted some of the most terrifying predators ever to swim: prehistoric sharks. One of the most bizarre was Helicoprion, a creature so strange that scientists struggled for over a century to understand how it actually worked. One of the weirdest looking prehistoric animals has to be the Helicoprion. If you start at the tail and move up, it looks like a normal shark right up until the top where its mouth begins. The lower jaw ends in a circular saw-like shape that makes it look like it belongs in a Bond villain’s lair. It’s hard to believe that this strange and terrifying creature once roamed this planet.

The mystery surrounding Helicoprion shows us just how much we still don’t know about these ancient seas. Ancient chondrichthyans, the class of animals that include sharks and rays, often leave little behind for researchers. Their bodies are mainly made of cartilage which is difficult to preserve. In the case of the Helicoprion, this means that researchers first discovered them through their confusing array of teeth. No one really knew where these chompers fit as there was little left of their overall bodies to give them clues about the rest of the animal.

The Whale Pretenders: Early Marine Mammals

Not all the giants of the prehistoric seas were reptiles or fish. Basilosaurus, meaning “king lizard,” is a prehistoric sea creature with a deceptive name. Despite its reptilian title, it was actually one of the earliest whales, evolving from land-dwelling mammals during the late Eocene epoch. This massive creature, reaching an average length of 18 meters (59 ft), patrolled the ancient oceans with its long, serpentine body and surprisingly small flippers.

What makes Basilosaurus so fascinating is that it represents a crucial transition in evolution – the move from land back to sea. Basilosaurus evolved from a land-dwelling animal that looked a lot like a goat. These terrestrial roots can be seen on its body, which has tiny, 35cm-long hind limbs that would have been of little use in water. Its modern descendants, blue whales, orcas, and dolphins, also possess these evolutionary ‘leftovers’, though theirs are internalised and truly vestigial. Still, they’re throwbacks to a time when their ancestors were a lot smaller and ran rather than swam.

The Great Extinction: When Giants Fell

The story of these incredible creatures has a dramatic ending. At the end of the Cretaceous Period, an asteroid colliding with Earth brought on a global mass extinction. A lingering impact winter halted photosynthesis on land and in the oceans, which had a major impact on food availability and was devastating for ammonites. This catastrophic event didn’t just affect the dinosaurs – it completely restructured marine ecosystems.

The extinction was particularly devastating for certain groups. At least 57 species of ammonites, which were widespread and belonged to six superfamilies, were extant during the last 500,000 years of the Cretaceous, indicating that ammonites remained highly diverse until the very end of their existence. All ammonites were wiped out during or shortly after the K-Pg extinction event, caused by the Chicxulub impact. It has been suggested that ocean acidification generated by the impact played a key role in their extinction, as the larvae of ammonites were likely small and planktonic, and would have been heavily affected.

Interestingly, some groups survived while others didn’t. Nautiloids, however, which had ancient relatives that lived at the same time as ammonites, survived this mass extinction. It’s thought this is in part linked to these groups’ preferred water depths. “Nautilus survived probably because it lives deeper in the ocean. This shows us that even small differences in lifestyle could mean the difference between extinction and survival.

Living Fossils and Modern Connections

What’s remarkable is that we can still see echoes of this ancient world today. Marine Reptiles Today” showcases the modern descendants of ancient marine reptiles. While less diverse today, species like the leatherback turtle, saltwater crocodile, marine iguana, monitor lizard and the sea snake continue to thrive in today’s oceans.

Scientists use these prehistoric creatures to understand our modern world. Shelled marine animals can help us look back into the past at what was going on in terms of climate change following extinction events. If we have known periods of warming or cooling, we can then infer that into modern climate science. The study of ammonites and other fossils gives us crucial insights into how marine ecosystems respond to dramatic environmental changes – knowledge that’s becoming increasingly important as we face our own climate challenges.

Conclusion

The Jurassic aquarium was a world of wonders that surpassed even our wildest imagination. From the gentle giants with impossibly long necks to the streamlined hunters with eyes the size of dinner plates, from living submarines with spiral shells to bullet-shaped cephalopods, these ancient seas teemed with life in ways that make today’s oceans seem almost empty by comparison.

These creatures remind us that life finds extraordinary ways to adapt and thrive, creating forms so fantastic they seem almost mythical. The Jurassic seas weren’t just a prelude to today’s oceans – they were a completely different world, filled with evolutionary experiments that push the boundaries of what we thought was possible in marine life.

Next time you look out at the ocean, try to imagine it as it was 200 million years ago. Picture massive marine reptiles gliding through crystal-clear waters, enormous ammonites drifting like living nautical instruments, and prehistoric sharks with circular saws for jaws patrolling the depths. The Jurassic aquarium may be gone, but its legacy lives on in every tide pool, every coral reef, and every creature that calls the ocean home. What would you have wanted to see most in those ancient seas?