Picture this: you’re standing in a natural history museum, staring at the massive skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus Rex. That towering predator once ruled the Earth for millions of years, yet it vanished in what scientists call a geological instant. Now imagine if we could somehow prevent our own species from following that same path into history books that future beings might never write.

The Fossil Record’s Stark Warning Signs

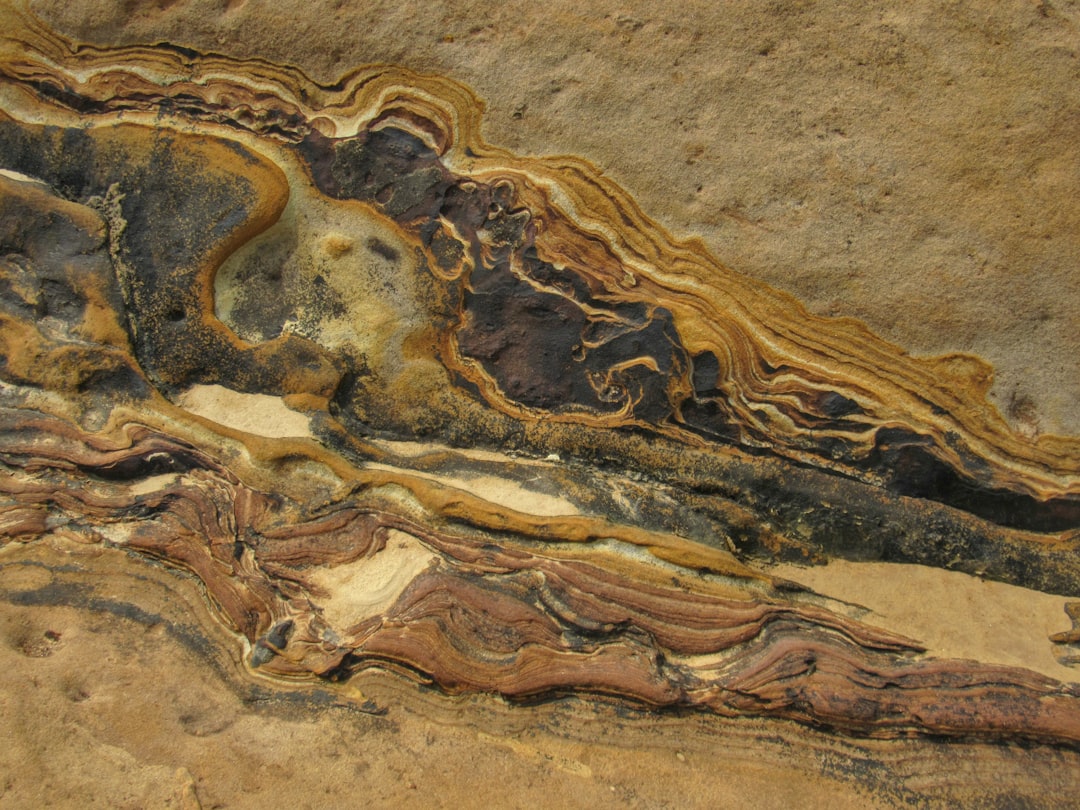

When paleontologists examine ancient rock layers, they uncover a chilling pattern that repeats throughout Earth’s history. In the strata corresponding to these time periods, the lower, older rock layer contains a great diversity of fossil life forms, while the younger layer immediately above is depauperate in comparison. This isn’t just bad luck or poor preservation – it’s the signature of mass extinction events that wiped out entire ecosystems.

Using such techniques, geologists estimate that some of these massive extinctions took place in 200,000 years or less. Either way, this represents a sudden event when compared to life’s 3.5 billion year history. Think of it this way: if Earth’s entire history was compressed into a single year, some mass extinctions would be over in just a few hours.

Why Some Species Survive While Others Perish

The fossil record reveals fascinating patterns about who lives and who dies during catastrophic events. Mass extinctions tend to preferentially remove spatially-restricted species, rather than the ones that are widespread, and that immediately gives us an idea about which lineages are most resistant to human activities…that they tend to be the rats, weeds, and cockroaches of the world, rather than the exquisitely adapted organisms that we often value highly.

This harsh reality teaches us something crucial about conservation today. The species we cherish most – the polar bears perfectly adapted to Arctic ice, the specialized orchids that bloom in specific forest conditions – are often the most vulnerable when environmental chaos strikes. Though each mass extinction is certainly unique, David’s work highlights their regularities – for example, the fact that they all seem to spare widespread genera.

Meanwhile, the generalists keep trucking along. It’s not exactly inspiring, but it’s a pattern that’s held true for hundreds of millions of years.

The Big Five and What They Teach Us

Earth has experienced at least five major mass extinction events, each offering distinct lessons for modern conservation efforts. End Permian (252 million years ago): Earth’s largest extinction event, decimating most marine species such as all trilobites, plus insects and other terrestrial animals. Most scientific evidence suggests the causes were global warming and atmospheric changes associated with huge volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia.

The End-Permian extinction, often called “The Great Dying,” eliminated roughly ninety-five percent of marine species and seventy percent of terrestrial vertebrates. What’s particularly unsettling is how closely the suspected causes mirror our current environmental crisis. End of the Cretaceous (66 million years ago): Extinction of many species in both marine and terrestrial habitats including pterosaurs, mosasaurs and other marine reptiles, many insects, and all non-Avian dinosaurs.

Each extinction event shows us that when multiple stressors hit simultaneously – climate change, habitat destruction, chemical changes in the atmosphere and oceans – life gets squeezed from all sides. There’s rarely just one smoking gun.

Climate Change as the Ultimate Game-Changer

But climate change is playing an increasingly important role in the decline of biodiversity. Climate change has altered marine, terrestrial, and freshwater ecosystems around the world. It has caused the loss of local species, increased diseases, and driven mass mortality of plants and animals, resulting in the first climate-driven extinctions.

Ancient climate upheavals show us what happens when temperatures shift too rapidly for ecosystems to adapt. On land, higher temperatures have forced animals and plants to move to higher elevations or higher latitudes, many moving towards the Earth’s poles, with far-reaching consequences for ecosystems. The risk of species extinction increases with every degree of warming.

They also found strong support for the first two hypotheses: animals that lost a large portion of their habitat to climate change were more likely to go extinct than those that did not, and cold-tolerant animals were less likely to go extinct than temperature-sensitive species. This ancient pattern is playing out today in real-time, from coral reefs bleaching in overheated oceans to Arctic species losing their icy homes.

The Domino Effect: When One Extinction Triggers Another

Perhaps the most alarming lesson from the fossil record is how extinctions cascade through ecosystems like falling dominoes. While nearly one million species are currently at risk of extinction, the United Nations University (UNU) in Bonn is drawing attention to “co-extinctions”: the chain reaction occurring when the complete disappearance of one species affects another. The domino effect could lead to more species going extinct and eventually even to the collapse of entire ecosystems.

Modern examples make this crystal clear. In a finely tuned ecological dance, sea otters prey on sea urchins, halting the unrestrained growth of sea urchin populations. Without the presence of otters, these spiky grazers run rampant, transforming lush kelp forests into desolate ‘urchin barrens’. But the demise of sea otters would have impacts that extend far beyond the disappearance of kelp alone, UNU said.

Each species exists within an intricate web of relationships. Pull out enough threads, and the whole tapestry unravels.

Early Warning Systems: Detecting Trouble Before It’s Too Late

Scientists are developing sophisticated methods to spot approaching ecological disasters before they become unstoppable. Such approaches have been termed early warning signals and represent a set of methods for identifying statistical changes in the underlying behaviour of a system across time or space that would be indicative of an approaching tipping point.

This allows for a dramatic improvement in the ability to detect climate change and early warnings of climatic tipping points. This allows for a dramatic improvement in the ability to detect climate change and early warnings of climatic tipping points. Think of it like monitoring a patient’s vital signs before they go into cardiac arrest – subtle changes in the data can reveal that a system is losing stability.

For tipping points that occur because of a bifurcation, it may be possible to detect whether a system is getting closer to a tipping point, as it becomes less resilient to perturbations on approach of the tipping threshold. These systems display critical slowing down, with an increased memory (rising autocorrelation) and variance. When ecosystems start behaving erratically, it’s often a sign they’re approaching a point of no return.

Conservation Success Stories: Proof That Action Works

Despite the grim lessons from the fossil record, recent research offers genuine hope that conservation efforts can work. The new study found that conservation actions improved the state of biodiversity or slowed its decline in most cases (66%) compared with no action taken at all. And when conservation interventions work, they were generally found to be highly effective.

The meta-analysis found that conservation actions – including the establishment and management of protected areas, the eradication and control of invasive species, the sustainable management of ecosystems, habitat loss reduction and restoration – improved the state of biodiversity or slowed its decline in the majority of cases (66%) compared with no action taken at all. And when conservation interventions work, the paper’s co-authors found that they are highly effective.

Even better, conservation gets more effective as we learn from our mistakes. This might also explain why the authors found a correlation between more recent conservation interventions and positive outcomes for biodiversity – conservation is likely getting more effective over time.

The Biotechnology Revolution in Conservation

Cutting-edge genetic tools are opening unprecedented possibilities for saving species from extinction. Biotechnologies can enhance conservation outcomes by accelerating evolutionary processes, restoring genetic diversity, and fostering the long-term recovery of endangered species. This is why we are creating the Genetic Rescue Toolkit.

The sixth mass extinction does not have to come to pass – with biotechnologies we can stop it. We can revive species and restore ecosystems for millennia to come. From cryopreserving genetic material to using gene editing to boost disease resistance, technology offers tools that past conservationists could only dream of.

However, these aren’t magic bullets. While traditional conservation tools, including habitat restoration and captive breeding, are critical aspects of species recovery, they cannot keep pace with the extinction crisis and cannot restore genetic diversity lost from living populations. Technology amplifies our conservation toolkit but doesn’t replace the fundamentals of protecting habitats and reducing threats.

Global Cooperation: The Ultimate Conservation Strategy

The fossil record shows that mass extinctions affect the entire planet, and our response must be similarly global in scope. I also urge countries to take urgent action to drastically reduce emissions, adapt to climate extremes, prevent pollution and put the brakes on biodiversity loss, including recognizing the role Indigenous Peoples play in protecting biodiversity. And all Governments must create new national climate plans that align with limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, as well as national biodiversity strategies that implement the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

In November 2024, at COP16 in Cali, Colombia, countries reached a historic consensus, including on the functioning of a fund, known as the Cali Fund, aimed at mobilizing new streams of funding for biodiversity action worldwide and boosting the implementation of the framework. It is set to receive contributions from private sector entities making commercial use of data from genetic resources, with the aim to raise an additional $200 billion each year by 2030 to close the global biodiversity finance gap.

Money talks, and the international community is finally putting serious funding behind biodiversity protection. Indigenous communities, who manage some of the world’s most biodiverse landscapes, are increasingly recognized as essential partners in this effort.

Addressing Root Causes, Not Just Symptoms

Conservation efforts must start addressing the underlying drivers of biodiversity loss, rather than just the symptoms, and advance solutions that can protect biodiversity at scale and minimize extinction risk. The fossil record teaches us that surface-level fixes rarely work when facing existential threats.

The main driver of biodiversity loss remains humans’ use of land – primarily for food production. Human activity has already altered over 70 per cent of all ice-free land. When land is converted for agriculture, some animal and plant species may lose their habitat and face extinction.

In shedding more light on co-extinctions, UNU said that intense human activities, such as land-use change, overexploitation, climate change, pollution and the introduction of invasive species, is causing an extinction acceleration that is at least tens to hundreds of times faster than the natural process of extinctions. In the last 100 years, over 400 vertebrate species were lost, for example.

We need systemic changes in how we produce food, consume resources, and power our societies – not just more protected areas around the edges.

The Race Against Time: Why Speed Matters

Regardless, scientists agree that today’s extinction rate is hundreds, or even thousands, of times higher than the natural baseline rate. Judging from the fossil record, the baseline extinction rate is about one species per every one million species per year.

This acceleration puts us in uncharted territory. Current extinction rates, for example, are around 100~1,000 times higher than the baseline rate, and they are increasing. The ongoing sixth mass extinction may be the most serious environmental threat to the persistence of civilization, because it is irreversible. Thousands of populations of critically endangered vertebrate animal species have been lost in a century, indicating that the sixth mass extinction is human caused and accelerating.

Unlike past mass extinctions caused by asteroid impacts or massive volcanic eruptions, this one is entirely within human control – which makes it both more tragic and more hopeful. We have the power to stop it, but time is running short.

Building Resilient Ecosystems for the Future

The fossil record reveals that ecosystems with greater diversity and more complex food webs tend to be more resilient during crisis periods. Conservation efforts must extend beyond individual species to encompass entire ecosystems”, Ms. Sebesvari said. “Urgent and decisive action is needed to preserve the resilience of ecosystems and ensure the survival of our planet’s diverse web of life.

In large part, conservation is about removing or reducing those factors and doing so for the most vulnerable species and in the places where species are most vulnerable. Much of the task of conservation professionals is to protect habitats large enough to house viable populations of species, first deciding where the priorities should be and sometimes restoring habitats that already have been destroyed.

The goal isn’t just to save individual species in zoos and botanical gardens, though those efforts matter. We need to maintain entire functioning ecosystems that can weather future storms. Large, connected habitats give species room to move and adapt as conditions change.

Hope From the Ashes: Recovery After Catastrophe

Perhaps the most inspiring lesson from the fossil record is that life always finds a way to bounce back after mass extinctions. Mass extinctions are typically followed by evolutionary bursts or radiations within surviving groups of organisms, such as mammals after dinosaurs became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous. The combined effect of mass extinctions and the following evolutionary bursts is that new groups of organisms fill niches previously filled by now-extinct org

Recovery takes millions of years, which isn’t much comfort to those of us alive today. But it shows that Earth’s capacity for regenerating biodiversity is virtually limitless, given enough time and the right conditions. However, our results clearly show that there is room for hope. Conservation interventions seemed to be an improvement on inaction most of the time; and when they were not, the losses were comparatively limited.

Every conservation success, no matter how small, creates seeds for future recovery. Protecting what remains gives evolution the raw materials to work with as conditions eventually stabilize.

Conclusion: Writing a Different Ending

The fossil record offers us a stark choice: we can be the asteroid that ends the age of mammals, or we can be the first species in Earth’s history to consciously prevent a mass extinction. The lessons are clear – act fast, think big, address root causes, and work together globally.

Staring down the pathway toward a sixth mass extinction, we stand at a critical juncture in history. Yet, amidst the challenges, we find cause for hope in the transformative potential of genetic rescue technologies. By embracing innovation and genetic rescue, we chart a course toward a brighter, sustainable future.

Unlike the dinosaurs, we can see the metaphorical asteroid coming. We have early warning systems, proven conservation methods, international cooperation mechanisms, and revolutionary biotechnology tools. The question isn’t whether we can prevent the next big die-off – it’s whether we’ll choose to act on everything the fossil record has taught us.

Did you expect that the bones buried in ancient rocks could offer such a clear roadmap for saving our modern world?