During the Mesozoic Era, the coastlines of North America teemed with a remarkable diversity of life. From towering dinosaurs patrolling the beaches to massive marine reptiles ruling the prehistoric seas, these ancient shorelines represented dynamic ecosystems where terrestrial and aquatic worlds converged. The ever-shifting boundaries between land and sea created unique environmental niches that supported specialized creatures, many of which have no modern equivalents. This fascinating period in Earth’s history reveals how coastal environments influenced the evolution of some of the most spectacular creatures ever to inhabit our planet.

The Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway

During much of the Cretaceous period (145-66 million years ago), North America was divided by a vast inland sea known as the Western Interior Seaway. This massive body of water stretched from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, effectively splitting the continent into eastern and western landmasses. The shallow, warm waters of this seaway created thousands of miles of new coastline habitat, dramatically reshaping North American ecosystems. Fossil evidence indicates that this environment supported incredibly diverse marine communities, including massive predatory fish, enormous sea turtles, and various marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. The Western Interior Seaway also influenced terrestrial ecosystems along its edges, creating extensive coastal wetlands, lagoons, and estuaries where specialized dinosaurs and other land animals thrived.

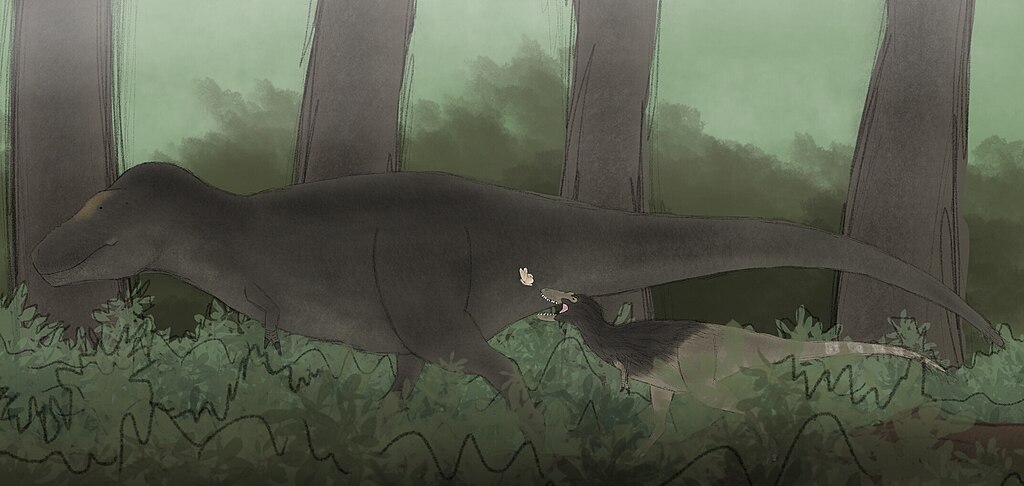

Tyrannosaurus Rex: Coastal Hunter

Recent paleontological evidence suggests that Tyrannosaurus rex, often portrayed as a creature of inland forests and plains, may have frequently hunted along coastal areas. Fossils of this apex predator have been discovered in ancient shoreline deposits across western North America, particularly in areas that once bordered the Western Interior Seaway. These massive carnivores, reaching lengths of up to 40 feet and weights exceeding 9 tons, likely took advantage of the abundant food sources concentrated near water bodies. The coastal environments would have attracted a variety of potential prey animals, from fish-eating pterosaurs to migrating hadrosaurs and ceratopsians. T. rex’s powerful jaws and serrated teeth were well-suited for dismembering large carcasses that may have washed ashore, suggesting these titanic predators might have occasionally scavenged marine animals in addition to actively hunting terrestrial prey.

Mosasaurs: Dragons of the Deep

Mosasaurs represent some of the most fearsome marine predators in North America’s ancient seas. These massive aquatic reptiles, distant relatives of modern monitor lizards and snakes, evolved to dominate the marine ecosystem during the Late Cretaceous period. Some species, like Mosasaurus hoffmannii, reached lengths exceeding 50 feet, with powerful paddle-like limbs, a streamlined body, and a long tail adapted for swimming. What made mosasaurs particularly deadly was their double-hinged jaw that allowed them to swallow large prey whole, complemented by multiple rows of sharp, conical teeth. Fossil evidence from places like the Pierre Shale in South Dakota and the Smoky Hill Chalk in Kansas reveals that these marine reptiles fed on fish, ammonites, sea turtles, birds, and even other mosasaurs. Their fossils are often found in sediments that represent relatively shallow marine environments, suggesting they frequently patrolled coastal waters where prey was abundant.

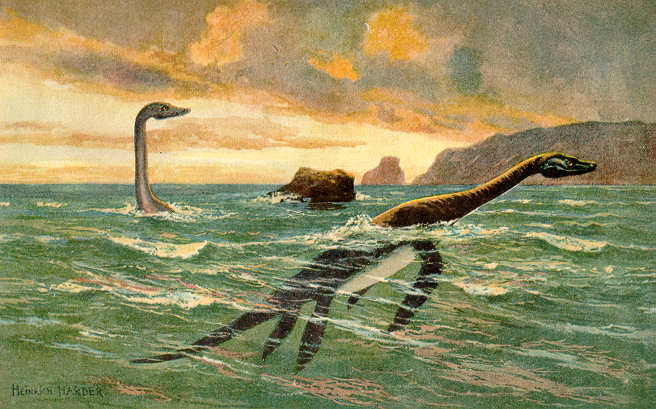

Plesiosaurs: Long-Necked Hunters

Plesiosaurs were among the most distinctive marine reptiles inhabiting North America’s prehistoric coastlines. These remarkable creatures possessed a unique body plan featuring a barrel-shaped torso, four powerful flipper-like limbs, and, in many species, an extraordinarily long neck topped with a relatively small head. This unusual anatomy has no direct modern equivalent, making plesiosaurs among the most distinctive animals in Earth’s history. Specimens discovered across North America, particularly from the Western Interior Seaway deposits, show remarkable diversity in their form and likely feeding strategies. Short-necked, large-headed varieties (pliosaurs) like Brachauchenius were active predators that could tackle large prey, while long-necked forms like Elasmosaurus, which could exceed 40 feet in length with necks containing over 70 vertebrae, likely specialized in hunting smaller prey with lightning-quick strikes from their flexible necks. Evidence suggests these reptiles gave birth to live young in the water rather than returning to land to lay eggs, making them fully committed to marine life.

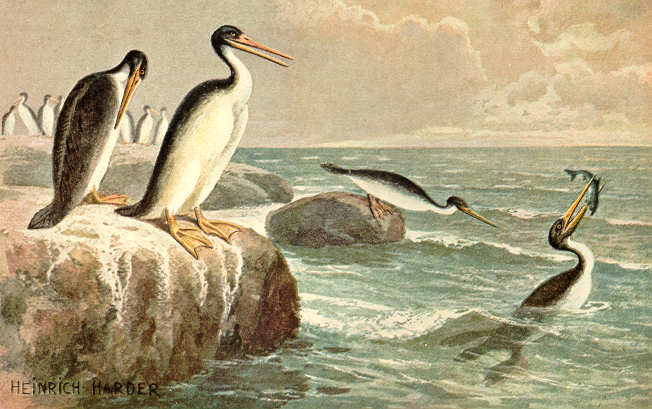

Pterosaurs: Masters of Coastal Skies

The skies above North America’s ancient shorelines were dominated by pterosaurs, flying reptiles that evolved diverse adaptations for coastal living. Unlike their depictions in popular media as simple “flying dinosaurs,” pterosaurs represent a separate reptilian lineage that developed powered flight independently of birds. Late Cretaceous North American shores hosted some of the largest flying animals ever to exist, including Quetzalcoatlus, with its staggering 36-foot wingspan. Fossil evidence from Texas, Montana, and Alabama reveals specialized coastal pterosaurs with adaptations for fishing, including elongated jaws filled with needle-like teeth perfect for grasping slippery prey. Some species possessed throat pouches similar to modern pelicans for scooping up fish, while others likely waded in shallow waters probing for crustaceans and mollusks. Pterosaur tracks discovered in coastal sediments suggest these animals frequently walked on firm ground along shorelines, contradicting earlier notions that they were awkward on land.

Hesperornithiformes: Toothed Diving Birds

The coastal waters of Cretaceous North America were home to a remarkable group of specialized aquatic birds known as hesperornithiformes. Unlike modern birds, these ancient avians retained teeth in their beaks, a primitive characteristic inherited from their dinosaurian ancestors. Species like Hesperornis regalis grew to impressive sizes, with some reaching lengths of up to 6 feet. These birds evolved highly specialized adaptations for a fully aquatic lifestyle, including powerful hind limbs positioned far back on their bodies for efficient underwater propulsion, similar to modern loons and grebes. Their wings became dramatically reduced to the point of flightlessness, as they evolved to become expert underwater hunters. Hesperornithiform fossils have been discovered in marine deposits from Kansas to the Canadian Arctic, indicating they were widespread across the Western Interior Seaway. Analysis of these fossils suggests they fed primarily on fish and may have nested in colonies along protected shorelines, much like modern seabirds.

Hadrosaurs: Coastal Plant-Eaters

Hadrosaurs, often called “duck-billed dinosaurs,” were among the most successful herbivores along North American shorelines during the Late Cretaceous period. These large ornithischian dinosaurs thrived in coastal environments, with fossil evidence suggesting they often lived in large herds that migrated along shorelines. Species like Edmontosaurus and Parasaurolophus possessed specialized dental batteries containing hundreds of teeth that were perfect for processing fibrous coastal vegetation such as cycads, conifers, and early flowering plants. Their distinctive bills were likely covered with a keratinous beak in life, allowing them to crop vegetation efficiently. Remarkably well-preserved specimens from Alberta and Wyoming show these animals had webbed feet, suggesting they were comfortable moving through shallow water and may have used coastal waterways as migration routes or to escape predators. Trackways discovered in coastal sediments from Alaska to Mexico provide further evidence that these dinosaurs frequently inhabited shoreline environments.

Prehistoric Crocodilians: Rulers of the Intertidal Zone

Ancient North American shorelines hosted a diverse array of crocodilian relatives far more varied than their modern descendants. During the Cretaceous period, these reptiles evolved specialized adaptations for different ecological niches within coastal environments. Massive predators like Deinosuchus, which could reach lengths exceeding 30 feet, lurked in estuaries and river mouths, capable of ambushing even large dinosaurs that came to drink. Unlike modern crocodilians, some prehistoric species evolved fully marine lifestyles, including streamlined bodies, paddle-like limbs, and tail fins for efficient swimming in open waters. Fossil evidence from Texas and Mississippi reveals that certain species possessed crushing teeth specialized for feeding on hard-shelled prey like turtles and mollusks, while others retained more traditional sharp teeth for grasping fish and other vertebrates. The remarkable diversity of these ancient crocodilians demonstrates how coastal environments fostered evolutionary experimentation, producing forms quite unlike anything seen today.

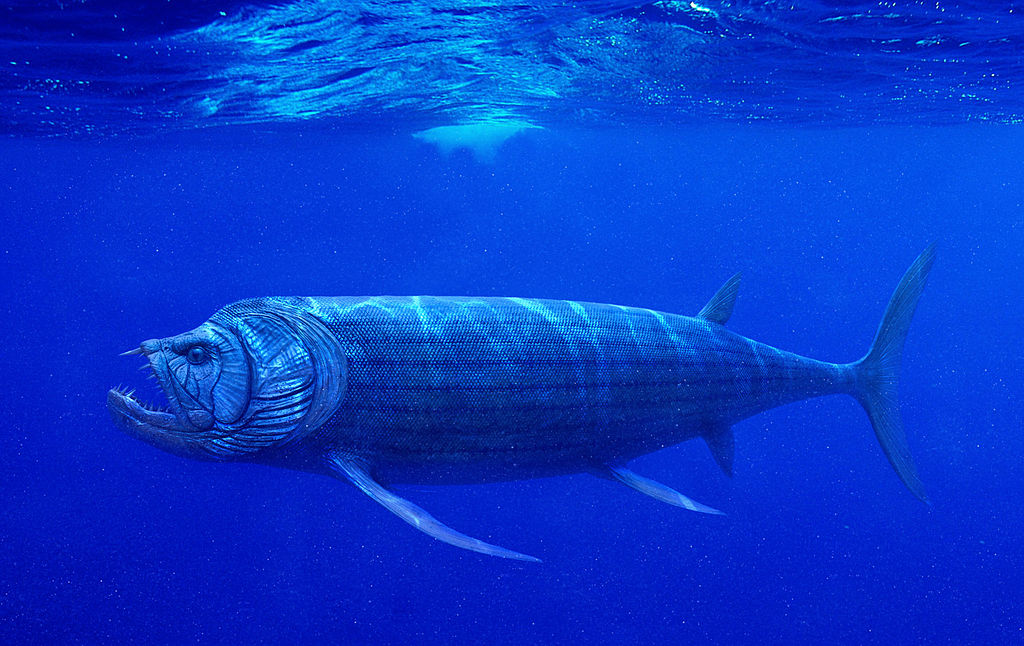

Xiphactinus: The Bulldog of the Sea

One of the most fearsome bony fish to patrol North America’s prehistoric coastlines was Xiphactinus, an enormous predator that resembled a monstrous version of a modern tarpon. This incredible fish could reach lengths of 18-20 feet, with a massive bulldog-like face featuring fang-like teeth protruding from its jaws even when closed. Remarkably complete fossils discovered in Kansas chalk deposits include one spectacular specimen containing the intact remains of another large fish within its body cavity, providing direct evidence of its voracious feeding habits. This “fish-within-a-fish” fossil suggests Xiphactinus sometimes attempted to swallow prey so large that it caused fatal internal injuries to the predator itself. Analysis of its skeletal structure indicates Xiphactinus was a powerful swimmer capable of explosive acceleration to capture prey, likely hunting in the middle depths of the Western Interior Seaway. Its large eyes suggest it relied heavily on vision to locate prey, and its streamlined body form allowed it to pursue fast-swimming victims through open water.

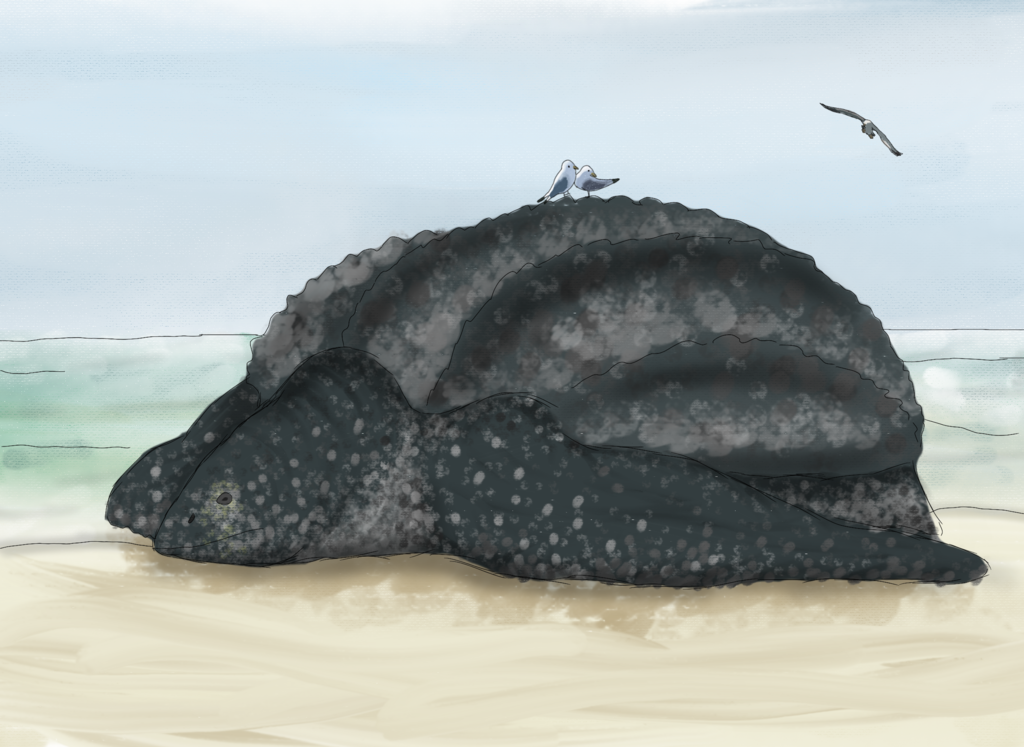

Archelon: The Colossal Sea Turtle

The Late Cretaceous seas of North America were home to Archelon, the largest turtle that ever lived. This massive marine reptile dwarfed modern sea turtles, with a shell length approaching 15 feet and an estimated weight exceeding 2 tons. Unlike modern sea turtles with their solid shells, Archelon had a reduced, leathery carapace with a skeletal framework that likely decreased its weight and increased maneuverability in the water. Fossils discovered in South Dakota and Wyoming reveal powerful flippers that would have propelled this giant efficiently through the shallow seas of the Western Interior Seaway. Analysis of its jaw structure suggests Archelon fed primarily on soft-bodied prey like jellyfish and squid, though it likely also consumed crustaceans and mollusks. Like modern sea turtles, Archelon probably needed to return to shorelines to lay eggs, creating a crucial connection between marine and terrestrial ecosystems along prehistoric North American coastlines.

Ammonites: Shelled Sentinels of Ancient Seas

The shallow coastal waters surrounding North America during the Mesozoic teemed with ammonites, shelled cephalopods that resembled nautilus but were more closely related to modern squid and octopuses. These animals, with their distinctive coiled shells that sometimes reached diameters exceeding three feet, represented vital components of marine food webs. Ammonite fossils are remarkably abundant in coastal deposits across the continent, with sites in Montana, South Dakota, and Texas yielding thousands of specimens representing dozens of species. Their intricate shell chambers functioned as sophisticated buoyancy control systems, allowing these mollusks to move up and down in the water column with minimal energy expenditure. Many species possessed specialized jaw structures for feeding on plankton, small fish, and crustaceans. The shells of ammonites underwent dramatic changes over time, with some Late Cretaceous forms evolving uncoiled or helical shapes that departed dramatically from the typical spiral pattern, reflecting ongoing evolutionary experimentation until their ultimate extinction alongside non-avian dinosaurs.

Dinosaur Diversity Along Ancient Shorelines

Beyond the well-known hadrosaurs and tyrannosaurs, North American coastal environments supported a remarkable diversity of dinosaurian life. Ceratopsians like Triceratops often inhabited coastal plains and deltas, where rich vegetation provided abundant food for these horned herbivores. Fossil evidence from Montana and Alberta suggests that certain ankylosaurs, heavily armored dinosaurs with club-like tails, frequently occupied coastal habitats where their tank-like bodies and defensive adaptations helped protect them from large predators. Small, bird-like theropods including dromaeosaurs (“raptors”) and troodontids hunted along beaches and estuaries, preying on fish, small mammals, and invertebrates. Remarkably, some dinosaur nesting sites have been discovered in what were ancient coastal environments, suggesting certain species may have deliberately selected shoreline areas for reproduction. The preservation of dinosaur tracks in coastal sediments across the continent provides further evidence of the importance of these transitional environments to dinosaurian ecology, revealing behavioral patterns that bone fossils alone cannot demonstrate.

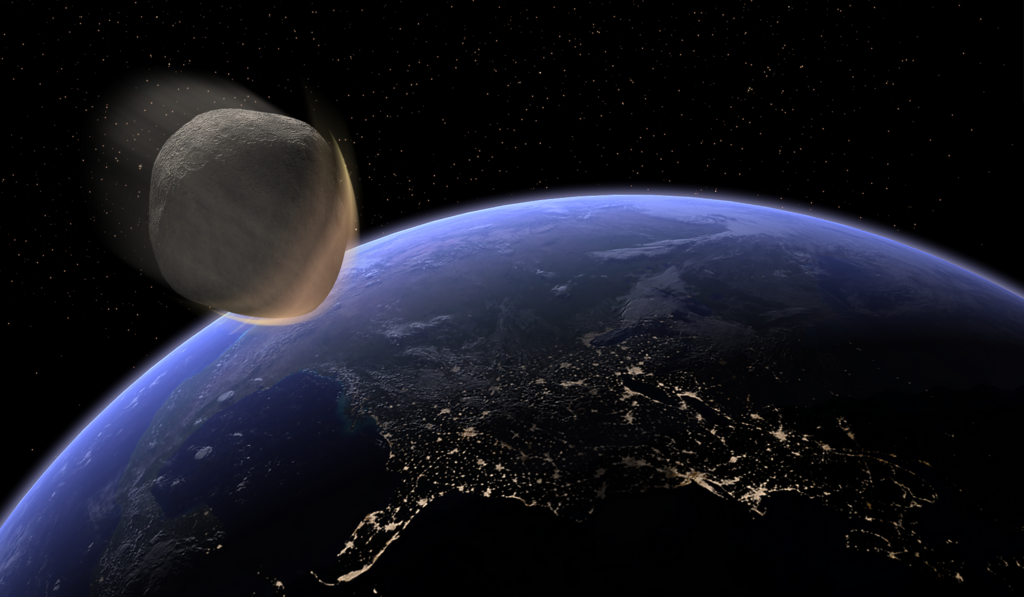

The End-Cretaceous Extinction Event

The vibrant coastal ecosystems of North America came to a catastrophic end approximately 66 million years ago during the end-Cretaceous extinction event. This global cataclysm, triggered primarily by a massive asteroid impact at what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, had particularly devastating effects on shoreline environments. The impact generated enormous tsunamis that scoured coastlines across the continent, with geological evidence of these massive waves preserved in deposits from Texas to North Dakota. Acid rain and global cooling following the impact severely disrupted marine food chains, leading to the collapse of entire ecosystems. Marine reptiles including mosasaurs and plesiosaurs disappeared completely, as did the ammonites and many specialized fish species. On land, all non-avian dinosaurs perished, leaving coastal niches vacant for surviving species to eventually exploit. The fossil record reveals a stark transition at this boundary, with the rich diversity of Mesozoic coastal life suddenly replaced by a dramatically impoverished assemblage of survivor species that would eventually diversify to create entirely new coastal ecosystems during the subsequent Cenozoic Era.

The story of North America’s prehistoric shorelines offers a fascinating glimpse into lost worlds where giants ruled the land, sea, and sky. These ancient coastal environments served as dynamic interfaces between terrestrial and marine ecosystems, fostering remarkable evolutionary innovations and supporting complex food webs. While the creatures that once dominated these shores have long vanished, their fossilized remains continue to provide valuable insights into Earth’s biological history. By studying these prehistoric coastal communities, scientists gain a deeper understanding of how ecosystems respond to environmental changes over time – knowledge that becomes increasingly relevant as we face modern challenges to our own coastal environments. The dinosaurs and marine giants of ancient North America remind us that our familiar shorelines have witnessed dramatic transformations throughout geological history, and will undoubtedly continue to evolve long after our own species has passed into the fossil record.