When we imagine prehistoric elephants roaming ancient landscapes, two iconic creatures often come to mind: mammoths and mastodons. Though frequently confused with one another, these magnificent animals were distinct species with unique characteristics that helped them thrive in different environments during the Pleistocene epoch. Both became extinct thousands of years ago, leaving behind only fossils, frozen specimens, and endless fascination. This article explores the key differences between these prehistoric proboscideans, from their evolutionary history to their ultimate disappearance.

Evolutionary Origins: Different Branches of the Elephant Family Tree

Mammoths and mastodons may look similar at first glance, but they belong to entirely different evolutionary branches within the order Proboscidea. Mammoths (genus Mammuthus) were members of the family Elephantidae, making them much closer relatives to modern elephants. They shared a common ancestor with today’s Asian and African elephants around 6 million years ago. Mastodons (genus Mammut), on the other hand, belonged to the family Mammutidae, which diverged from the elephant family tree much earlier – approximately 25-30 million years ago. This evolutionary difference meant that despite superficial similarities, mastodons were about as related to mammoths as humans are to certain monkeys – clearly part of the same broader group, but representing distinct evolutionary paths.

Timeline of Existence: When Did They Roam the Earth?

The timeline of mammoths and mastodons overlapped significantly, but mastodons appeared first in the fossil record. Mastodons originated in Africa around 30 million years ago before spreading to Europe, Asia, and eventually North America roughly 15 million years ago. Mammoths evolved later, with the earliest mammoth species appearing approximately 5 million years ago in Africa before migrating to Europe and Asia. The most famous species, the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), evolved around 400,000 years ago in Siberia. Both mastodons and mammoths shared the landscape with early humans and only disappeared relatively recently – most populations vanished between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago, although some isolated mammoth populations survived on remote islands until as recently as 4,000 years ago, making them contemporary with ancient Egyptian civilization.

Physical Size and Build: Structural Differences

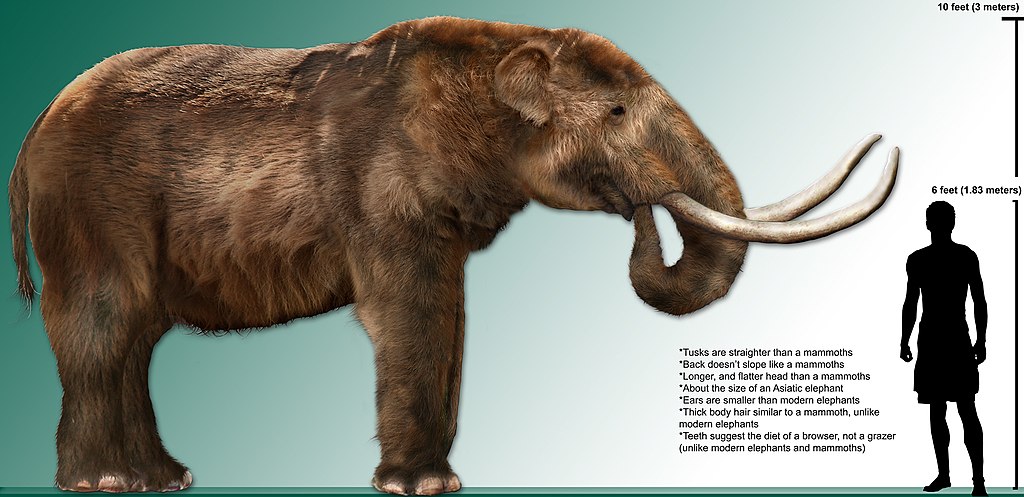

When comparing physical dimensions, mammoths generally stood taller than mastodons. The largest mammoth species, the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), could reach heights of up to 14 feet at the shoulder and weigh up to 10 tons. Woolly mammoths were somewhat smaller, typically standing about 9-11 feet tall. Mastodons were more compact and robust, standing between 8-10 feet tall with a stockier, more muscular build compared to the relatively slender frame of mammoths. The mastodon’s body was built lower to the ground with shorter legs proportional to their body size, giving them a distinctly different silhouette. This stockier build was well-adapted to pushing through dense forests and brush, contrasting with the mammoth’s more open-country adaptations. The skeletal structures also differed, with mammoths having longer limbs and a more elevated spine compared to the mastodon’s more horizontal posture.

Tusks: Length, Shape, and Function

One of the most distinctive features of both animals was their impressive tusks, which differed dramatically in form and function. Mammoth tusks were extraordinarily long (up to 15 feet in some specimens), dramatically curved, and often twisted in a characteristic spiral pattern – especially in males. These enormous tusks likely served multiple purposes: sexual display, fighting between males, and possibly for clearing snow to reach vegetation in winter. Mastodon tusks, while still impressive, were generally straighter, shorter (typically 6-8 feet long), and less curved. They were also thicker proportionally and lacked the spiral twisting seen in mammoth tusks. Evidence suggests mastodon tusks were practical tools for stripping bark from trees, digging for roots and tubers, and breaking branches to access preferred foods. The different tusk structures perfectly reflect the different feeding strategies and environmental adaptations of these two proboscideans.

Dentition: Specialized Teeth for Different Diets

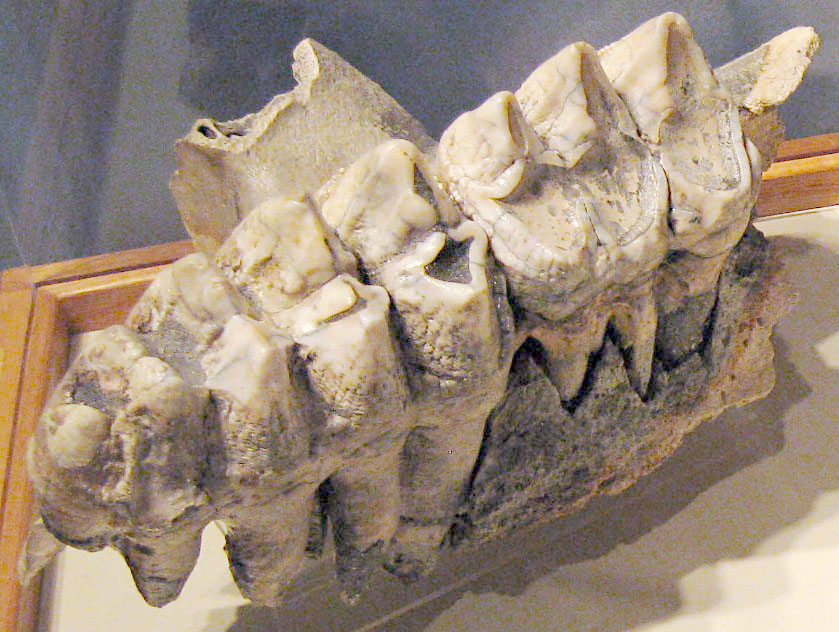

Perhaps the most scientifically significant difference between mammoths and mastodons lies in their teeth, which reveal profound differences in their diets and ecological niches. Mammoths possessed high-crowned molars with numerous flattened enamel ridges arranged in tight rows, creating efficient grinding surfaces ideal for processing grasses and other abrasive plant materials. These teeth were similar to those of modern elephants but with more ridges – adaptations for the mammoth’s grass-dominated diet. Mastodons, conversely, had distinctly different molars with cone-shaped cusps arranged in pairs (hence their name, which means “breast tooth” in Greek). These teeth were perfect for crushing leaves, twigs, and other woody vegetation but would have been inefficient for processing grasses. The dental differences represent perhaps the clearest anatomical evidence of how these animals occupied different feeding niches even when living in the same regions.

Habitat Preferences: Where They Thrived

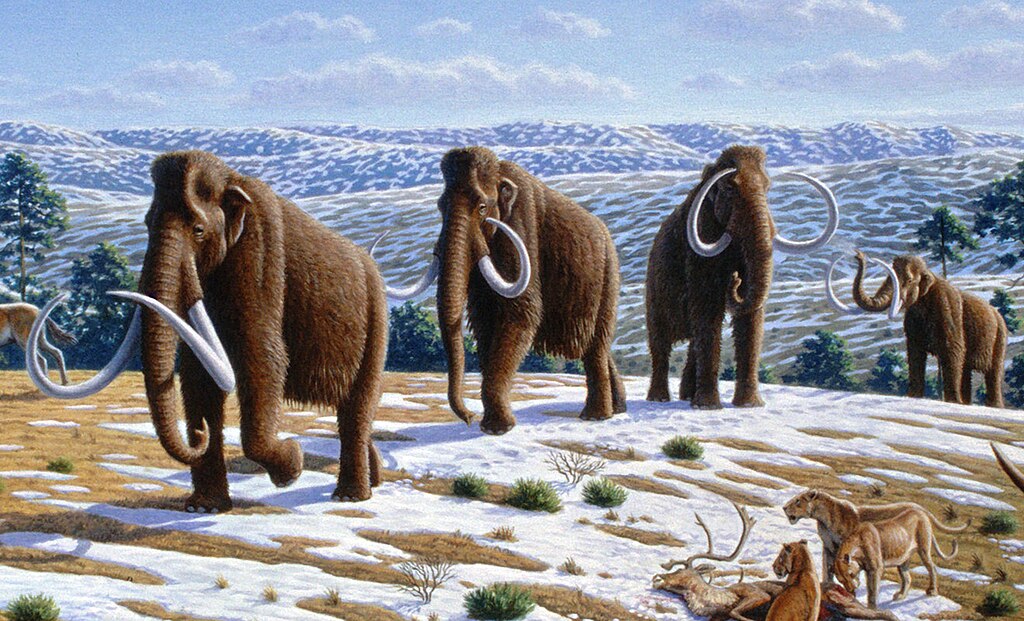

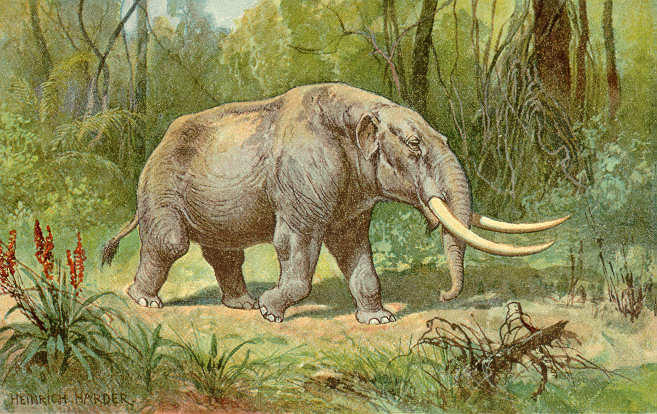

Their different physical adaptations reflected the preferred habitats of these prehistoric giants. Mammoths were primarily creatures of open landscapes – the vast grassland steppes, tundra, and prairies that covered much of the Northern Hemisphere during the Pleistocene. Their high-crowned teeth were perfectly adapted for processing the silica-rich grasses that dominated these environments. Mastodons, with their browser-type dentition, inhabited more forested environments, particularly woodland edges, marshy areas, and mixed coniferous forests. Fossil evidence shows mastodons favored regions with abundant trees, shrubs, and diverse plant life rather than open plains. This habitat differentiation helps explain how these two proboscideans could coexist across much of North America without excessive competition – they simply exploited different parts of the landscape and different food resources, a classic example of ecological niche partitioning.

Dietary Specializations: Grazers vs. Browsers

The dietary preferences of mammoths and mastodons represent one of their most fundamental differences. Mammoths were primarily grazers, with a diet dominated by grasses, sedges, rushes, and other low-growing herbaceous vegetation. Isotopic analysis of mammoth remains confirms they consumed mainly C3 grasses and plants typical of cool, open environments. Mastodons, by contrast, were dedicated browsers who fed on leaves, twigs, conifers, and woody vegetation. Studies of preserved mastodon dung and stomach contents have revealed remains of conifer twigs, leaves, seeds, mosses, and even aquatic plants. Microscopic wear patterns on mastodon teeth confirm they processed much softer, less abrasive vegetation than the silica-rich diet of mammoths. This dietary specialization meant that even when their ranges overlapped, they weren’t directly competing for the same food resources.

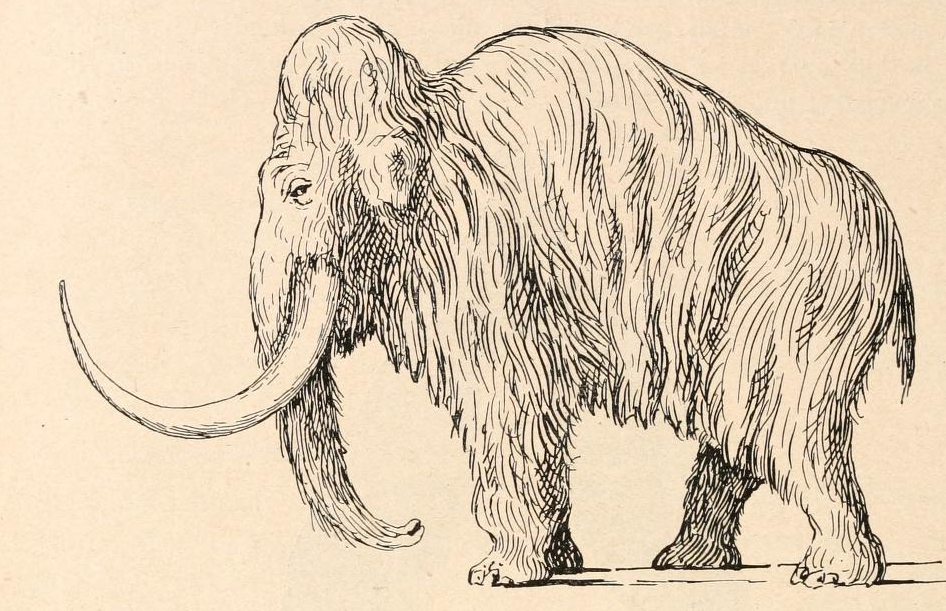

Hair and Insulation: Adaptations to Climate

The woolly mammoth is famous for its thick, shaggy coat – an adaptation to the harsh Arctic environments it inhabited. This mammoth species possessed a complex insulation system consisting of an outer layer of long guard hairs (up to 3 feet in length) and a dense undercoat of shorter, crimped wool-like fur. Additionally, woolly mammoths had a thick layer of subcutaneous fat up to 4 inches deep. While other mammoth species living in more temperate regions likely had less extensive hair covering, most had some degree of hair as insulation. Mastodons, primarily forest dwellers of more temperate regions, appear to have had a much less extensive hair covering based on the limited preserved evidence. Though some mastodon specimens show evidence of hair, particularly around the shoulders and neck, they lacked the extreme cold-weather adaptations seen in woolly mammoths. Their forest habitat would have provided more natural shelter from wind and weather extremes, reducing the need for extensive insulation.

Geographic Distribution: Where They Lived

The geographic ranges of mammoths and mastodons show both overlap and important differences. Mammoths achieved an impressively wide distribution across multiple continents. Various mammoth species inhabited Africa, Europe, Asia, and North America, with the woolly mammoth ranging from Western Europe across northern Asia and into North America. Mastodons had a more limited distribution, primarily concentrated in North and Central America, although earlier mastodon relatives had lived in parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa. In North America, the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) ranged from Alaska to central Mexico and from coast to coast, but was most common in the eastern forests and the Great Lakes region. Where their ranges overlapped, particularly in parts of North America, mammoths typically dominated in open grasslands and plains, while mastodons were more prevalent in forested regions, wetlands, and mixed habitats with abundant browse vegetation.

Famous Fossil Discoveries: Where to See Them Today

Several remarkable discoveries have enhanced our understanding of both prehistoric animals. For mammoths, the best-preserved specimens come from permanently frozen ground in Siberia and Alaska. The most famous is likely “Lyuba,” a one-month-old woolly mammoth calf discovered in 2007 so perfectly preserved that her internal organs remained intact after over 40,000 years. For mastodons, the most complete skeleton was discovered in 1845 in Newburgh, New York, and became known as the “Warren Mastodon” – it remains on display at the American Museum of Natural History. Another significant discovery occurred in 1989 when the “Snowmastodon” site in Colorado revealed the remains of at least 35 American mastodons, providing unprecedented insight into mastodon social structure. Today, impressive mammoth and mastodon displays can be found in major natural history museums worldwide, including the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, the Royal British Columbia Museum, the Field Museum in Chicago, and the Natural History Museum in London.

Social Structure and Behavior: How They Lived

While behavioral patterns must be inferred from fossil evidence and comparisons with modern elephants, researchers have developed reasonable hypotheses about the social lives of these ancient proboscideans. Mammoths likely had social structures very similar to modern elephants, with family groups consisting of related females and their offspring led by a matriarch. Evidence from frozen specimens and fossil footprints suggests woolly mammoths traveled in herds, with males leaving the family unit upon reaching adolescence to either live solitarily or form loose bachelor groups. Mastodons may have been somewhat less social, possibly living in smaller family units or even pairing seasonally rather than maintaining large permanent herds. This hypothesis is supported by mastodon fossil sites typically containing fewer individuals than mammoth sites. Both species likely experienced musth – a period of heightened testosterone and aggression in males – as evidenced by injuries on male specimens consistent with combat. The social dynamics of both animals would have been shaped by their different habitat preferences, with the open-country mammoths potentially forming larger herds than the forest-dwelling mastodons.

Extinction Theories: Why They Disappeared

The disappearance of mammoths and mastodons remains one of paleontology’s most debated topics, with evidence pointing to multiple contributing factors. Climate change played a significant role as the warming period following the last ice age dramatically transformed landscapes, shrinking the steppe environments favored by mammoths and altering forest compositions that mastodons depended upon. Human hunting pressure represents another critical factor, with archaeological evidence showing Paleolithic humans actively hunted both species throughout their range. The “overkill hypothesis” suggests that even relatively small numbers of human hunters could have tipped the balance for already-stressed populations. Disease, reduced genetic diversity from population fragmentation, and reduced reproductive success in changing environments likely contributed as well. Most paleontologists now favor a “perfect storm” explanation where climate change reduced and fragmented suitable habitat, while human hunting delivered the final blow to already vulnerable populations. Interestingly, small populations of woolly mammoths survived on isolated islands until much more recently – as late as 4,000 years ago on Wrangel Island off Siberia.

De-Extinction Prospects: Could They Return?

The remarkable preservation of some mammoth specimens, with intact DNA, has fueled serious scientific discussion about potentially bringing these species back through genetic engineering. Several approaches are being considered, with the most promising involving CRISPR gene-editing technology to modify Asian elephant embryos with mammoth-specific genes for cold tolerance, hair production, and hemoglobin adaptations. The Colossal Biosciences company, founded by geneticist George Church, has raised significant funding to pursue this goal, hoping to produce mammoth-elephant hybrids within the next decade. Mastodon de-extinction presents greater challenges due to more limited genetic material and greater evolutionary distance from modern elephants. Beyond the technical hurdles, ethical questions abound: Would recreated animals truly be mammoths or just elephant-mammoth hybrids? Would they suffer health problems? Could appropriate habitats support them? Would resources be better spent conserving endangered elephants? While de-extinction technology advances rapidly, whether we should resurrect these Ice Age giants remains as controversial as it is fascinating.

Conclusion

Mammoths and mastodons, though superficially similar, represent distinct evolutionary paths within the proboscidean family tree. From their different teeth and tusks to their preferred habitats and diets, these Ice Age giants evolved specialized adaptations that allowed them to thrive in complementary ecological niches. Mammoths, with their grazing diet and open-country adaptations, were essentially “elephant-like” creatures of grasslands and tundra. Mastodons, with their browsing habits and stockier builds, were forest specialists that occupied a completely different ecological role. Understanding these differences enhances our appreciation of prehistoric biodiversity and the complex ecosystems that existed during the Pleistocene. As scientists continue studying their remains and possibly even working toward de-extinction, these magnificent creatures continue to captivate our imagination and deepen our understanding of Earth’s ever-changing history.