The prehistoric oceans were arenas of epic power struggles, dominated by creatures that would make today’s marine life seem tame by comparison. For over 250 million years, various apex predators vied for supremacy in Earth’s ancient seas. Two groups stand out in this underwater competition for dominance: the fearsome marine reptiles—like ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs—and the ancient sharks, including the massive megalodon and its predecessors. Both groups evolved remarkable adaptations for marine life and occupied top predator positions throughout different geological periods. Their evolutionary arms race shaped marine ecosystems for millions of years, leaving behind fascinating fossil evidence of their reign. This article explores the comparative dominance, adaptations, and ultimate fates of these magnificent marine rulers.

The Timeline of Marine Dominance

The struggle for oceanic supremacy spans hundreds of millions of years, with different predators claiming the title of apex predator at various points. Sharks first appeared in the fossil record around 450 million years ago, evolving into increasingly sophisticated predators throughout the Paleozoic Era. Marine reptiles, by contrast, were relative newcomers, first appearing in the Early Triassic period about 250 million years ago when some land reptiles returned to the sea. The two groups would share the oceans for nearly 185 million years, with marine reptiles becoming extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period (66 million years ago), while sharks continued to evolve and persist to the present day. This long coexistence created fascinating instances of competition, adaptation, and ecological partitioning as these predators evolved alongside one another in Earth’s ancient oceans.

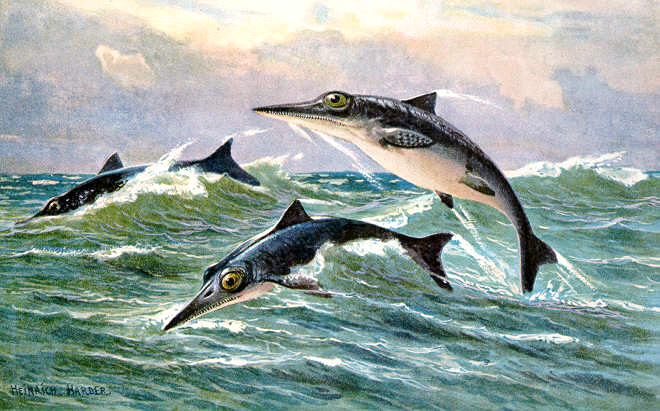

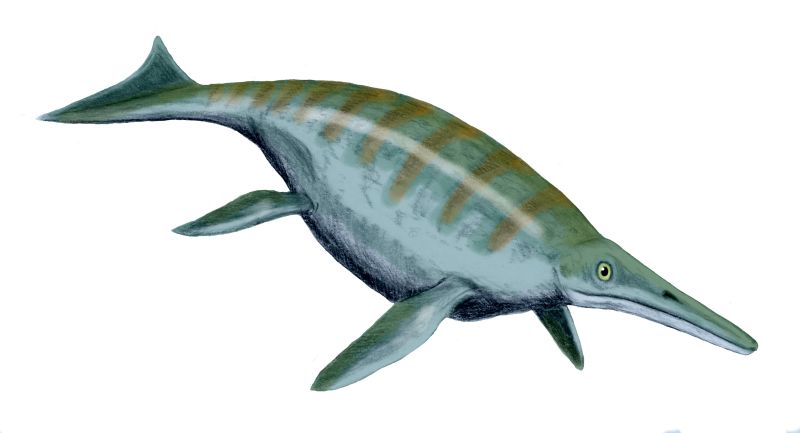

Ichthyosaurs: The Dolphin-like Marine Reptiles

Among the most remarkable marine reptiles were the ichthyosaurs, whose dolphin-like appearance represents one of evolution’s most striking examples of convergent evolution. These reptiles evolved from terrestrial ancestors but developed a streamlined body shape eerily similar to modern dolphins and tuna despite being unrelated. Some ichthyosaurs grew to massive sizes, with species like Shonisaurus reaching lengths of over 20 meters. Their large eyes—sometimes the size of dinner plates—suggest they were effective hunters in deep or dimly lit waters. Unlike sharks, ichthyosaurs gave birth to live young at sea rather than laying eggs, an adaptation that freed them from returning to land. At their peak during the Jurassic period, ichthyosaurs were among the ocean’s fastest and most efficient predators, though they declined mysteriously in the mid-Cretaceous, well before the mass extinction that claimed other marine reptiles.

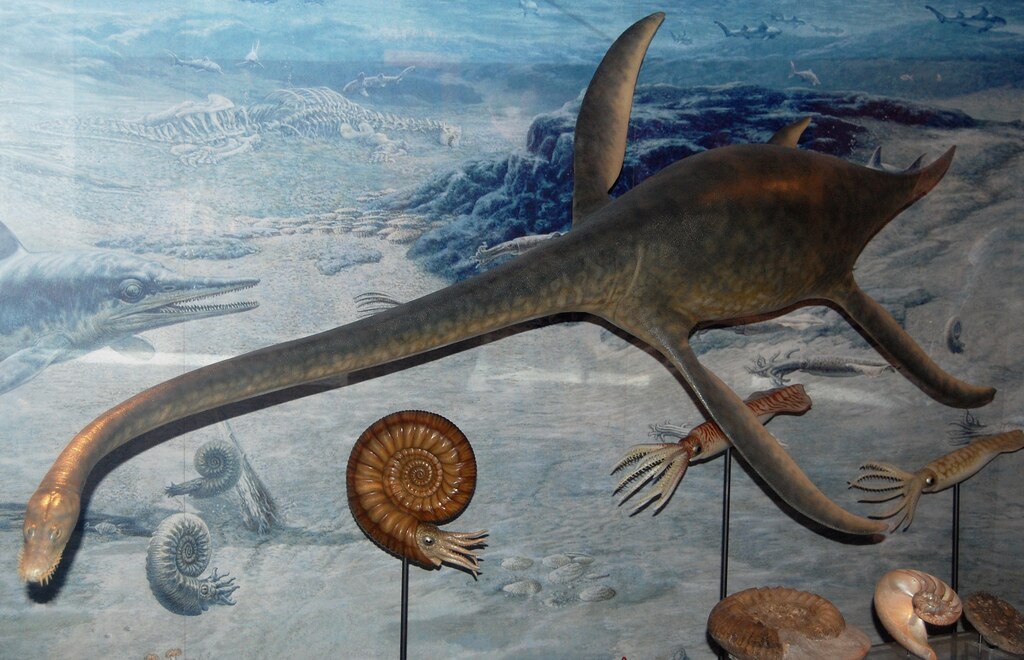

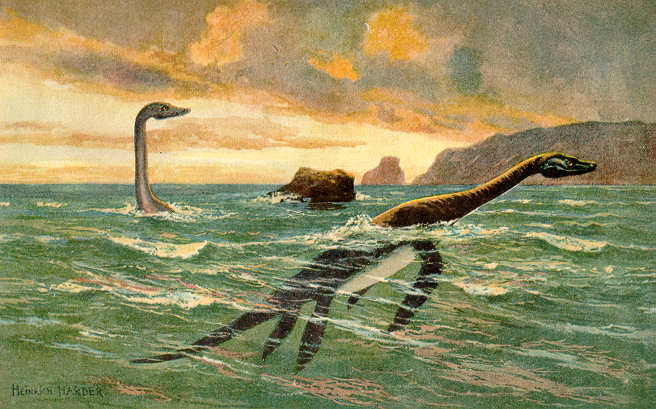

Plesiosaurs: The Long-Necked Hunters

Plesiosaurs represent one of the most distinctive body plans ever to evolve in marine vertebrates, featuring a small head on an extremely long neck, a rounded body, and four powerful flippers. These unique reptiles first appeared in the Late Triassic and persisted until the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Unlike the torpedo-shaped ichthyosaurs built for speed, plesiosaurs adopted a different hunting strategy, using their long necks to strike at prey from below or to reach into crevices for hidden food. The elasmosaurids, a family of plesiosaurs, took this adaptation to the extreme with necks containing more than 70 vertebrae—the highest number of any known vertebrate. Their four flipper propulsion system, similar to that of sea turtles but more powerful, allowed for remarkable maneuverability and possibly ambush tactics that sharks of the time couldn’t match. This distinctive body plan persisted for over 135 million years, suggesting it was a remarkably successful adaptation.

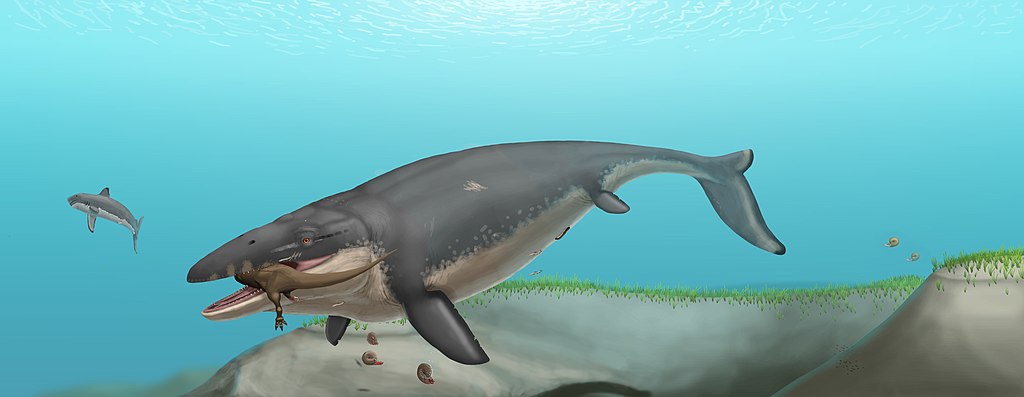

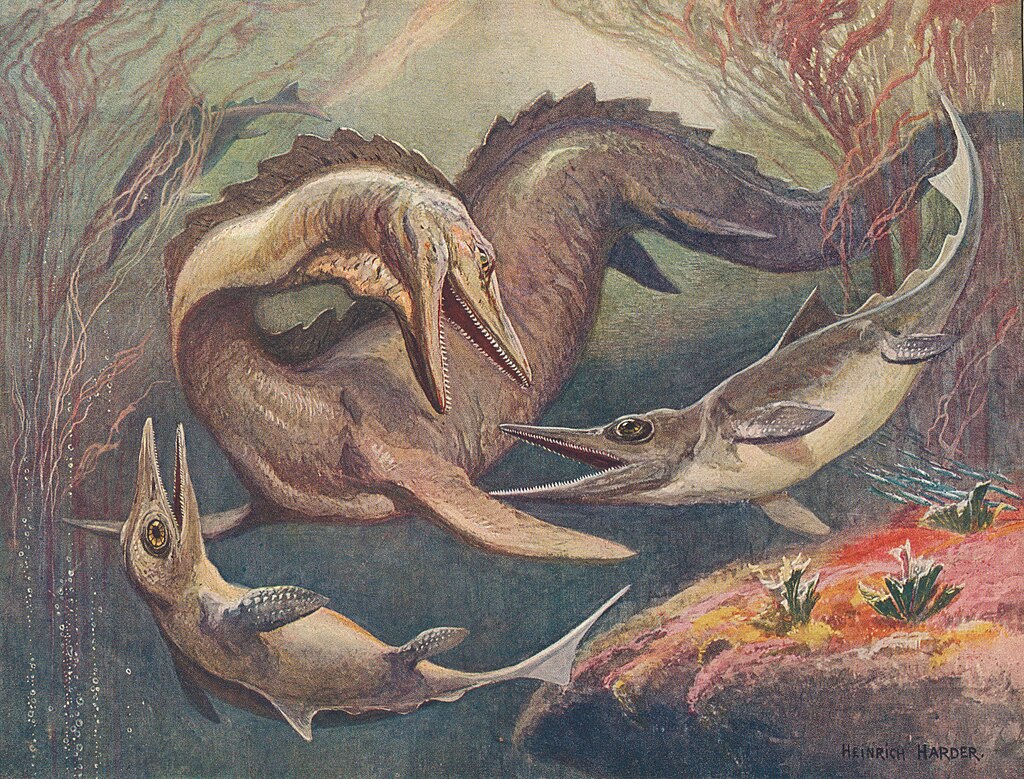

Mosasaurs: The Late Cretaceous Titans

As ichthyosaurs declined in the mid-Cretaceous, a new group of marine reptiles rose to dominance: the mosasaurs. These powerful predators, closely related to modern monitor lizards and snakes, ruled the oceans during the final 20 million years of the Cretaceous period. Mosasaurs evolved several shark-like features through convergent evolution, including a streamlined body and a powerful tail fin, though their propulsion method was more serpentine. The largest species, like Mosasaurus hoffmannii, reached lengths of up to 17 meters, making them comparable in size to many modern whale species. Unlike other marine reptiles, mosasaurs had double-hinged jaws and flexible skulls similar to those of snakes, allowing them to swallow large prey whole. Their teeth were designed for gripping rather than cutting, with some species developing crushing teeth specialized for shellfish. When mosasaurs achieved dominance in the Late Cretaceous, they became perhaps the most formidable marine predators of their time, capable of taking on virtually any prey in their environment.

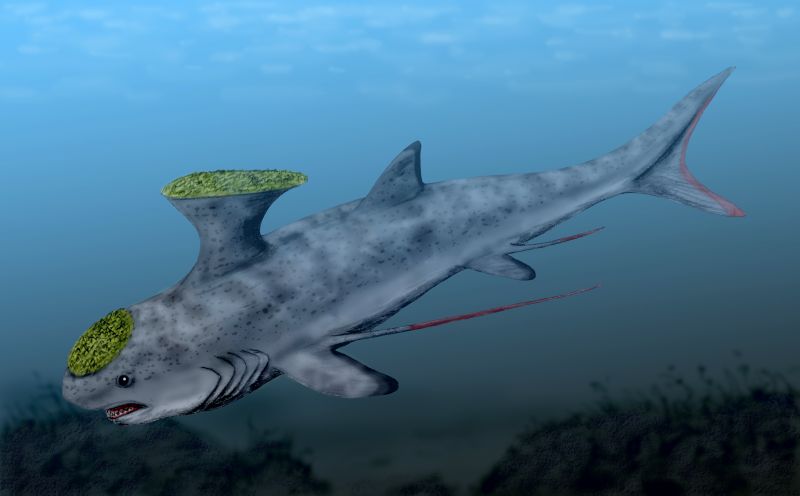

Ancient Sharks: Evolutionary Champions

Sharks represent one of evolution’s greatest success stories, having persisted for approximately 450 million years through multiple mass extinctions. Their basic design—a streamlined cartilaginous body with remarkable sensory adaptations—proved so effective that it has remained fundamentally unchanged for hundreds of millions of years. Throughout the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras, sharks diversified into numerous forms, some quite different from modern species. The bizarre Stethacanthus sported an anvil-shaped dorsal fin, while Helicoprion had a bizarre spiral-shaped tooth whorl in its lower jaw. During the time they coexisted with marine reptiles, sharks occupied numerous ecological niches, from small reef-dwelling hunters to open-ocean predators. Their continuous tooth replacement, electroreception capabilities, and efficient body design gave sharks significant advantages over many marine reptiles in certain hunting scenarios. Unlike the marine reptiles that ultimately went extinct, sharks’ evolutionary plasticity allowed them to adapt to changing ocean conditions throughout hundreds of millions of years.

Megalodon: The Ultimate Shark Predator

Long after marine reptiles vanished from Earth’s oceans, sharks achieved their evolutionary pinnacle with Otodus megalodon, the largest predatory fish ever known. Appearing approximately 20 million years ago and vanishing around 3.6 million years ago, megalodon represents the ultimate expression of shark predatory adaptation. Growing to an estimated length of 15-18 meters (with some estimates suggesting even larger sizes), megalodon had the most powerful bite force of any known animal, capable of crushing the bones of whales. Its teeth—sometimes exceeding 17 centimeters in length—were serrated cutting tools designed for attacking large marine mammals. Fossil evidence suggests megalodon was a cosmopolitan species, inhabiting most of the world’s oceans and targeting large prey like prehistoric whales and seals. Though megalodon never competed directly with the marine reptiles of the Mesozoic (having evolved long after their extinction), it represents the apex of shark evolution and demonstrates how sharks continued to develop formidable predatory adaptations long after marine reptiles disappeared.

Comparing Hunting Strategies

Marine reptiles and sharks employed distinctly different hunting approaches, shaped by their evolutionary origins and physical adaptations. Most large sharks, both ancient and modern, rely heavily on their acute sense of smell and the ability to detect electrical fields generated by prey, allowing them to hunt effectively even in murky waters or darkness. Their replaceable teeth and powerful jaws evolved specifically for predation, giving them formidable weapons. Marine reptiles, by contrast, were air-breathing descendants of land animals, relying more heavily on vision for hunting. Ichthyosaurs had extraordinarily large eyes optimized for underwater vision, while plesiosaurs likely used their mobility and unique body shape for specialized hunting techniques. Mosasaurs, with their snake-like jaws, could swallow large prey whole. The hunting methods also differed in energy expenditure—sharks can often cruise efficiently for long periods waiting for prey, while air-breathing marine reptiles needed to balance hunting with surfacing to breathe. These different approaches allowed these predator groups to frequently occupy the same ecosystems without direct competition by specializing in different prey or hunting techniques.

Anatomical Showdown: Speed and Agility

When comparing the physical capabilities of marine reptiles and sharks, fascinating patterns emerge in how these unrelated groups solved similar problems of aquatic locomotion. Ichthyosaurs achieved perhaps the most shark-like body form among marine reptiles, with a stiff, crescent-shaped tail fin that provided powerful thrust similar to that of modern tuna and sharks. Some ichthyosaurs may have reached speeds comparable to the fastest sharks, potentially exceeding 25 mph in short bursts. Plesiosaurs took an entirely different approach to locomotion, using their four large flippers in a flying motion unique among marine vertebrates—a method that provided exceptional maneuverability but likely less raw speed than ichthyosaurs or sharks. Ancient sharks displayed considerable diversity in body forms and swimming capabilities, from the sluggish bottom-dwelling types to the swift open-ocean hunters with bodies built for sustained pursuit. The competition between these groups likely drove the evolution of increasingly specialized body forms as they competed for resources in shared marine environments, resulting in remarkable examples of convergent evolution despite their different evolutionary origins.

Size Matters: Comparing Dimensions

Size often correlates with predatory dominance in marine ecosystems, and both marine reptiles and sharks achieved impressive dimensions. The largest known ichthyosaur, Shonisaurus sikanniensis, reached an estimated length of 21 meters—larger than a modern sperm whale. Among plesiosaurs, Elasmosaurus stretched approximately 14 meters, though much of this was neck rather than body mass. Mosasaurs grew to similarly impressive sizes, with Mosasaurus hoffmannii reaching up to 17 meters in length. Among ancient sharks, the massive Otodus megalodon holds the record at an estimated 15-18 meters, with some controversial estimates suggesting even larger individuals. When comparing these measurements, it’s important to consider not just length but body mass and bite force—megalodon had perhaps the most powerful bite of any known animal, estimated at up to 108,500-182,200 newtons (compared to around 3,000 newtons for a large modern great white shark). Throughout their long coexistence, marine reptiles and sharks engaged in an evolutionary arms race that pushed both groups toward larger sizes and more specialized predatory adaptations.

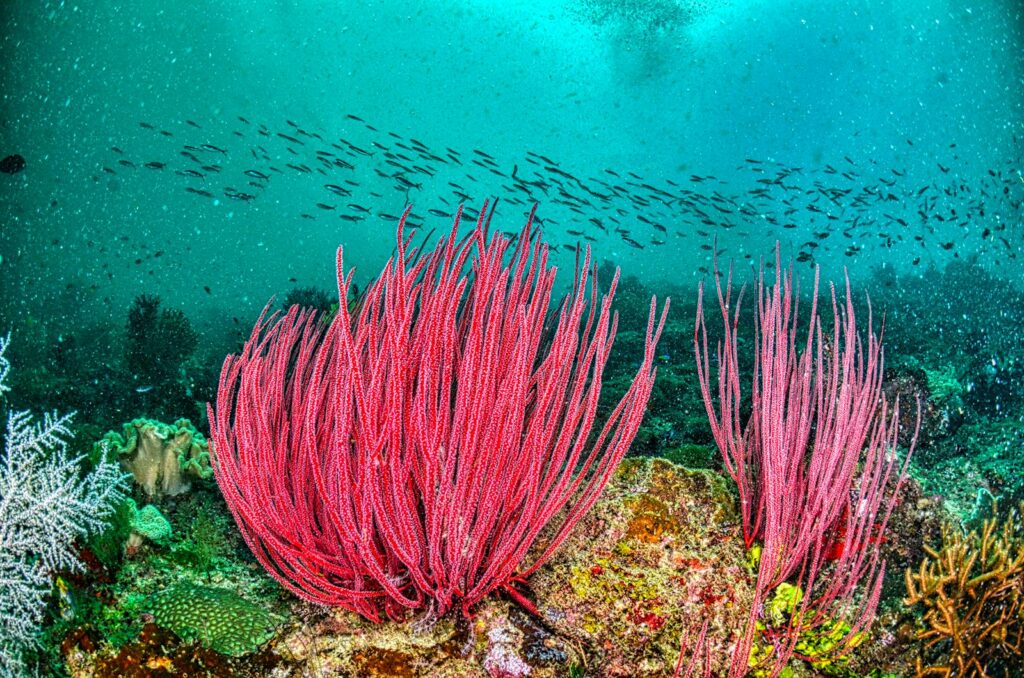

Ecological Niches and Coexistence

Despite competing as top predators, marine reptiles and sharks managed to coexist for over 180 million years by specializing in different ecological niches. Fossil evidence suggests they often partitioned food resources and hunting territories, reducing direct competition. Some ichthyosaurs specialized in diving to extreme depths, as evidenced by their large eyes and reinforced rib cages resistant to pressure, allowing them to hunt squid and other deep-water prey that many sharks couldn’t reach. Plesiosaurs with their unique body design likely specialized in ambush hunting techniques fundamentally different from shark hunting methods. Different shark species developed specialized dentition for various prey types—some evolved flat, crushing teeth for shellfish while others developed serrated cutting teeth for flesh. This ecological partitioning extended to breeding and nursery areas as well, with evidence suggesting marine reptiles and sharks utilized different coastal regions for reproduction. The fossil record indicates that marine ecosystem complexity increased throughout the Mesozoic era, creating more specialized niches that allowed for greater biodiversity among top predators without direct competition for the same resources.

The K-Pg Extinction: Why Sharks Survived

The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event 66 million years ago eliminated all marine reptiles but spared many shark lineages, raising fascinating questions about their differential survival. This catastrophic event, triggered by an asteroid impact and resulting global climate disruption, caused the collapse of marine food webs and eliminated approximately 75% of all species. Marine reptiles, as air-breathing animals that gave birth to relatively few, large offspring, proved vulnerable to these disruptions. Their complete extinction suggests they lacked the adaptations necessary to weather severe food shortages and environmental changes. Sharks, by contrast, demonstrated remarkable resilience, though they did not emerge unscathed—many larger species and specialized hunters disappeared while smaller, more generalist feeders survived. Several shark adaptations likely contributed to their survival: their ability to slow their metabolism during food shortages, their opportunistic feeding habits, their capacity to produce numerous offspring, and their occupation of diverse habitats from shallow coastal waters to the deep sea. These advantages allowed sharks to persist through an extinction event that completely eliminated their marine reptile competitors.

The Legacy in Modern Oceans

The ancient competition between marine reptiles and sharks has left lasting impressions on today’s ocean ecosystems. Modern sharks carry the evolutionary refinements developed during their long coexistence with marine reptiles, including sophisticated sensory systems, efficient body designs, and specialized feeding strategies. The ecological niches once occupied by marine reptiles were eventually filled by marine mammals—whales, dolphins, and seals—that returned to the oceans long after marine reptiles disappeared. Interestingly, these mammals independently evolved body forms and hunting strategies remarkably similar to those of extinct marine reptiles—modern dolphins bear striking resemblances to ichthyosaurs, while some whale feeding strategies parallel those theorized for plesiosaurs. This pattern of convergent evolution demonstrates the powerful selective pressures of marine environments. Today’s great white sharks, though considerably smaller than megalodon, employ hunting techniques that likely evolved during competition with marine reptiles. The modern oceans, though lacking marine reptiles, still reflect the evolutionary arms race that played out over hundreds of millions of years between these magnificent predatory groups.

Conclusion: Different Champions for Different Eras

The question of whether marine reptiles or ancient sharks “ruled the waters” defies a simple answer, as dominance shifted throughout their long coexistence. During the Jurassic period, ichthyosaurs likely held advantage in many marine ecosystems, while the Late Cretaceous saw mosasaurs achieve apex predator status in numerous ocean regions. Throughout this dynamic period, various shark species continued their own evolutionary journey, sometimes competing directly with marine reptiles and sometimes occupying completely different niches. What’s most remarkable is not which group dominated at any particular moment, but how their competition drove the evolution of increasingly specialized and formidable predatory adaptations. Marine reptiles ultimately faced extinction, while sharks persisted and continued to evolve, eventually producing the enormous megalodon long after marine reptiles disappeared. Today’s oceans, dominated by a mix of sharks and marine mammals, represent the latest chapter in this evolutionary saga. Both ancient marine reptiles and sharks deserve recognition as supreme oceanic predators, each group achieving remarkable evolutionary success through different adaptations and strategies, ruling the waters as champions of their respective eras.