Nestled within the annals of paleontological misunderstandings, perhaps no dinosaur has suffered a greater injustice than Oviraptor. Its very name—meaning “egg thief” in Latin—stands as a testament to a scientific error that persisted for decades. When first discovered in 1924 by Roy Chapman Andrews, the Oviraptor fossil was found atop what appeared to be a nest of Protoceratops eggs, seemingly caught in the act of theft. However, modern science has vindicated this misunderstood creature, revealing a far more complex and fascinating story about parental care in the prehistoric world. This article explores the true nature of Oviraptor, its remarkable adaptations, and how paleontologists eventually cleared its undeserved criminal record.

The Infamous Discovery: A Case of Mistaken Identity

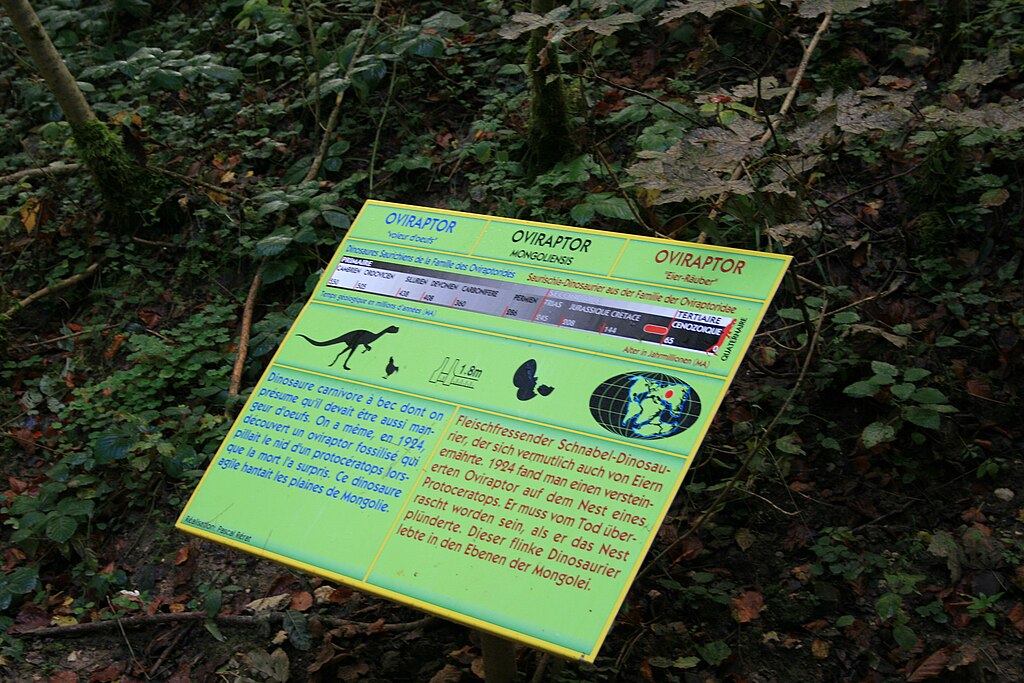

The story of Oviraptor begins in the sun-baked Gobi Desert of Mongolia during the American Museum of Natural History’s expeditions in the 1920s. In 1924, paleontologist Roy Chapman Andrews and his team made a startling discovery—a dinosaur skeleton positioned directly above a nest of what they believed to be Protoceratops eggs. Given the positioning and the creature’s unusual skull structure, scientists quickly jumped to conclusions. They named the new species “Oviraptor philoceratops,” literally meaning “egg thief, lover of ceratopsians,” assuming it had been caught in the act of raiding another dinosaur’s nest. This interpretation seemed logical at the time, especially considering the dinosaur’s unusual skull, which appeared perfectly adapted for crushing hard shells. The accusation stuck, and for nearly 70 years, Oviraptor carried the reputation of an egg-stealing villain in the popular and scientific imagination.

Physical Characteristics: Beyond the Beak

Oviraptor was a medium-sized theropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 75 million years ago. It stood about 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall and measured roughly 2 meters (6.5 feet) in length, with a relatively lightweight build of 33-40 kilograms (73-88 pounds). Its most distinctive feature was its parrot-like skull with a powerful, toothless beak and a bizarre crest on top that resembled a cassowary’s casque. This unusual head housed large eye sockets, indicating good vision, while its hands featured three long, flexible fingers perfect for grasping. Unlike many of its carnivorous theropod relatives, Oviraptor had a specialized jaw structure that suggested a more varied diet. Its relatively short, stiff tail and bird-like posture further emphasized its evolutionary relationship to modern avians, with many paleontologists now believing it had a feathered body—though direct evidence of feathers in Oviraptor itself remains limited.

The Vindication: From Thief to Nurturing Parent

The most dramatic reversal in Oviraptor’s reputation came in 1993 when a team led by Mark Norell discovered a new specimen in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. This remarkable fossil showed an Oviraptor positioned directly over a nest of eggs, with its limbs spread out in a distinctly brooding posture. Close examination of the eggs revealed they contained embryos of Oviraptor itself—not Protoceratops as originally thought in Andrews’ discovery. This groundbreaking evidence transformed scientific understanding: rather than stealing eggs, the original Oviraptor had likely been protecting its own nest when it was suddenly buried by a sandstorm or other natural disaster. Further specimens confirmed this interpretation, with multiple individuals found in similar brooding positions. The evidence was clear: far from being an egg thief, Oviraptor was a devoted parent that had given its life protecting its offspring—a behavior similar to many modern birds. This discovery represented one of paleontology’s most significant reputational rehabilitations, changing a villain into a symbol of parental devotion.

Oviraptoridae: A Diverse Family of Unusual Dinosaurs

Oviraptor belongs to a larger family of dinosaurs called Oviraptoridae, which has expanded significantly since the original discovery in 1924. This fascinating group now includes over a dozen genera, including Citipati, Khaan, and Rinchenia, all sharing distinctive characteristics like toothless beaks and elaborate cranial crests. The oviraptorids thrived primarily in Asia, with most fossils discovered across Mongolia and China, suggesting they were highly successful in these ecosystems during the Late Cretaceous. Unlike many dinosaur families with more uniform body plans, oviraptorids show remarkable diversity in size and skull morphology. Some species were quite small, while others like Gigantoraptor reached lengths of 8 meters (26 feet) and weighed over a ton. This variation suggests they occupied diverse ecological niches, with different feeding specializations and behaviors. Interestingly, brooding behavior appears to have been common across the family, with multiple genera found fossilized while sitting on nests, providing strong evidence for complex parental care throughout the group.

Dietary Habits: What Did Oviraptor Actually Eat?

Despite being wrongfully accused of egg theft, the question of Oviraptor’s actual diet has remained a subject of scientific debate. The dinosaur’s unusual skull morphology—featuring a robust, toothless beak and powerful jaw muscles—was initially interpreted as specialized for crushing eggs or shells. However, further research has suggested a much more diverse diet. Modern analyses indicate Oviraptor may have been omnivorous, consuming a variety of foods including plants, small vertebrates, insects, and possibly mollusks like clams or other shellfish. This interpretation is supported by the discovery of gastroliths—stomach stones used to grind food—associated with some specimens. Additionally, the beak structure bears similarities to modern seed-eating birds, suggesting plants may have formed a significant portion of its diet. While eggs might have occasionally been on the menu, they were certainly not its primary food source as originally believed. This dietary flexibility would have been advantageous in the semi-arid environments of the Late Cretaceous Gobi region, allowing Oviraptor to adapt to seasonal food availability.

Nesting Behavior: Pioneering Parental Care

The discovery of Oviraptor specimens in brooding positions has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur reproductive behavior. These remarkable fossils show the dinosaurs sitting directly on their nests, with their limbs symmetrically arranged around clutches of eggs in a distinctly bird-like manner. The nests themselves were carefully constructed, with eggs arranged in concentric circles containing up to 22 elongated eggs positioned with their narrow ends pointing toward the center. This arrangement allowed the parent to cover the maximum number of eggs with its body, suggesting sophisticated nesting strategies. Analysis of the skeletal positioning indicates these dinosaurs were not simply buried while laying eggs—they were actively incubating them, using body heat to warm the developing embryos. Some fossils even show evidence of a specialized “brood patch”—a region with increased blood vessels used by modern birds for efficient heat transfer to eggs. This behavior represents one of the earliest known examples of direct parental care in the dinosaur record, predating birds but clearly demonstrating the evolutionary roots of modern avian reproductive strategies.

Feathered Appearance: Reconstructing Oviraptor’s True Look

While no direct feather impressions have been found with Oviraptor specimens themselves, substantial evidence suggests these dinosaurs were likely covered in feathers. Closely related oviraptorosaurs like Caudipteryx and Protarchaeopteryx have been discovered with clear feather preservation, showing elaborate plumage including wing-like structures on their forelimbs and long tail feathers. Additionally, microscopic analysis of Oviraptor bones reveals anchor points for feathers similar to those in modern birds. Based on these lines of evidence, paleontologists now typically reconstruct Oviraptor with a fully feathered body, possibly featuring display plumage associated with its prominent head crest. The feathers would have served multiple functions, including insulation, display for mate attraction, and critically, assistance in brooding behavior by helping to shelter and warm eggs. Modern artistic reconstructions often depict Oviraptor with colorful plumage patterns, particularly around the head crest, reflecting the hypothesis that these features evolved partly for visual signaling among members of the species. Though speculative, these feathered reconstructions represent our best scientific understanding of how this remarkable dinosaur actually appeared.

The Gobi Desert Ecosystem: Understanding Oviraptor’s World

The environment in which Oviraptor lived provides crucial context for understanding its adaptations and lifestyle. During the Late Cretaceous period, the Gobi region of Mongolia was significantly different from today’s harsh desert. Paleoenvironmental evidence suggests it was a semi-arid ecosystem with seasonal streams and oases, supporting diverse plant life including conifers, ginkgoes, and cycads. This landscape experienced dramatic seasonal fluctuations, with periods of rainfall followed by extended dry spells. Oviraptor shared this environment with a variety of other dinosaurs, including the ceratopsian Protoceratops, the ankylosaur Pinacosaurus, various dromaeosaurs (“raptors”), and primitive mammals. The region was prone to sudden sandstorms that occasionally buried animals alive—creating the remarkably preserved fossils that have allowed paleontologists to study these creatures in such detail. These harsh conditions may explain some of Oviraptor’s adaptations, including its versatile feeding apparatus and dedicated parental care, which would have improved offspring survival rates in a challenging environment. The frequent preservation of Oviraptor in brooding postures suggests these sandstorms sometimes struck during nesting season, tragically freezing these prehistoric parents in their final acts of protection.

Evolutionary Relationships: Between Dinosaurs and Birds

Oviraptor occupies a fascinating position in the dinosaur evolutionary tree, representing a crucial transitional phase between non-avian dinosaurs and modern birds. As a member of the Maniraptora group, Oviraptor shared numerous characteristics with avian dinosaurs, including a wishbone (furcula), wrist bones allowing complex wing-like movements, and air sacs within its vertebrae for efficient breathing. Detailed cladistic analyses place oviraptorids as close relatives to both dromaeosaurs (like Velociraptor) and true birds, with all belonging to the overarching group Pennaraptora—meaning “feathered thieves.” This positioning makes Oviraptor particularly valuable for understanding the progression of bird-like features in dinosaur evolution. While Oviraptor itself was not a direct ancestor of birds (that honor belongs to earlier, smaller theropods), it represents a parallel evolutionary branch that developed many bird-like characteristics independently. This phenomenon, called convergent evolution, demonstrates how certain adaptations—including feathers, nesting behaviors, and skull modifications—evolved repeatedly in different lineages due to their adaptive advantages. Oviraptor thus provides a remarkable window into the evolutionary processes that eventually produced modern birds.

Cultural Impact: From Villain to Icon

The dramatic narrative of Oviraptor’s wrongful accusation and subsequent vindication has made it an enduring icon in paleontological circles and popular culture. Before its rehabilitation, Oviraptor appeared in media as a sneaky egg predator, reinforcing misunderstandings about dinosaur behavior. The 1993 discovery transforming its image coincided with growing scientific interest in dinosaur-bird connections, making Oviraptor a poster child for changing perspectives in paleontology. This redemption story has been featured in numerous documentaries, including major productions by PBS, BBC, and National Geographic, often portrayed as a classic example of how science corrects itself through new evidence. In museum exhibits worldwide, Oviraptor reconstructions now commonly show it protectively brooding its nest rather than raiding others. Modern children’s books have embraced this narrative shift, presenting Oviraptor as a sympathetic character and teaching young readers about scientific misconceptions. The dinosaur’s journey from villain to devoted parent resonates as a compelling story about both prehistoric life and the evolving nature of scientific understanding.

Modern Research: New Discoveries About Oviraptor

Research on Oviraptor and its relatives continues to yield fascinating new insights in the 21st century. Recent microscopic studies of Oviraptor eggshells have revealed porous structures suggesting the eggs were partially buried in substrate while being brooded—a reproductive strategy intermediate between reptiles and birds. Advanced CT scanning of fossil skulls has illuminated the brain structure of oviraptorids, indicating enhanced visual processing and coordination areas consistent with complex behaviors. A 2018 study analyzing melanosomes (pigment-bearing structures) in a close relative suggested these dinosaurs may have displayed reddish-brown coloration, providing the first clues about their actual appearance. Meanwhile, new specimens continue to be discovered across Asia, with a particularly rich oviraptorid fossil record emerging from the Nanxiong Formation in southern China, expanding our understanding of their geographic range. Perhaps most intriguingly, biochemical analysis of fossilized egg material has begun to reveal information about the incubation temperatures maintained by brooding oviraptorids, suggesting they maintained body temperatures between those of modern reptiles and birds—crucial evidence in understanding their physiology and metabolism.

The Legacy of a Naming Error

The misnaming of Oviraptor stands as one of paleontology’s most prominent nomenclature ironies. Unlike most scientific naming errors, which can be corrected through taxonomic revision, the rules of zoological nomenclature require that once formally published, a genus name remains valid regardless of later discoveries proving its etymology inaccurate. Consequently, Oviraptor remains permanently labeled as an “egg thief” despite being conclusively exonerated of this behavior. This peculiar situation has made Oviraptor a valuable teaching example in scientific education, demonstrating both the historical nature of science and the importance of avoiding hasty conclusions based on initial evidence. The case highlights how names can perpetuate outdated interpretations—modern paleontologists must consistently clarify that, despite its name, Oviraptor was no thief. Some researchers have embraced this contradiction, using it to emphasize the evolving nature of scientific knowledge. The Oviraptor naming error has also prompted greater caution in naming new species, with paleontologists now typically waiting for more comprehensive evidence before assigning behaviorally specific names to newly discovered prehistoric creatures.

Conclusion

From villain to vindicated parent, the story of Oviraptor represents one of paleontology’s most remarkable rehabilitations. This misunderstood dinosaur, wrongfully accused of egg theft based on circumstantial evidence, has emerged as a symbol of devoted parental care in the prehistoric world. Its discovery in brooding positions over its own eggs transformed our understanding of dinosaur behavior and provided critical evidence for the evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and birds. Today, Oviraptor stands not as a thief but as a testament to how scientific knowledge evolves through new discoveries and careful analysis. Though forever bearing a name that no longer reflects reality, this remarkable creature continues to fascinate researchers and the public alike, demonstrating sophisticated behaviors that challenge our preconceptions about these ancient animals. In the end, the dinosaur once branded a criminal has become one of paleontology’s most poignant success stories—a reminder that in science, as in justice, evidence eventually reveals the truth.