The ancient seas of the Mesozoic era were witness to one of nature’s most spectacular rivalries. While dinosaurs dominated the land, beneath the waves, a different drama unfolded between two mighty groups of marine reptiles – the graceful plesiosaurs and the powerful mosasaurs. These colossal predators would compete for supremacy of the oceans across millions of years, their rivalry shaping the very evolution of prehistoric marine ecosystems. Yet this wasn’t simply a tale of two similar beasts; it was a complex story of adaptation, timing, and ultimately, extinction.

Ancient Marine Ecosystem Dominance

The prehistoric oceans were far from empty waters. Angola’s Cretaceous seas were dominated by many species of large, carnivorous marine reptiles, creating an underwater world that would seem alien to modern observers. Unlike today’s oceans where whales and sharks rule supreme, the Mesozoic seas hosted multiple apex predators competing for the same resources.

Marine reptiles were especially successful in the Mesozoic as major predators in the sea. They were successful in becoming marine predators during the Age of Dinosaurs, when there were no mammalian competitors. This absence of mammalian competition allowed reptilian marine predators to evolve into ecological niches that would later be filled by whales and dolphins.

Timeline of Marine Reptile Evolution

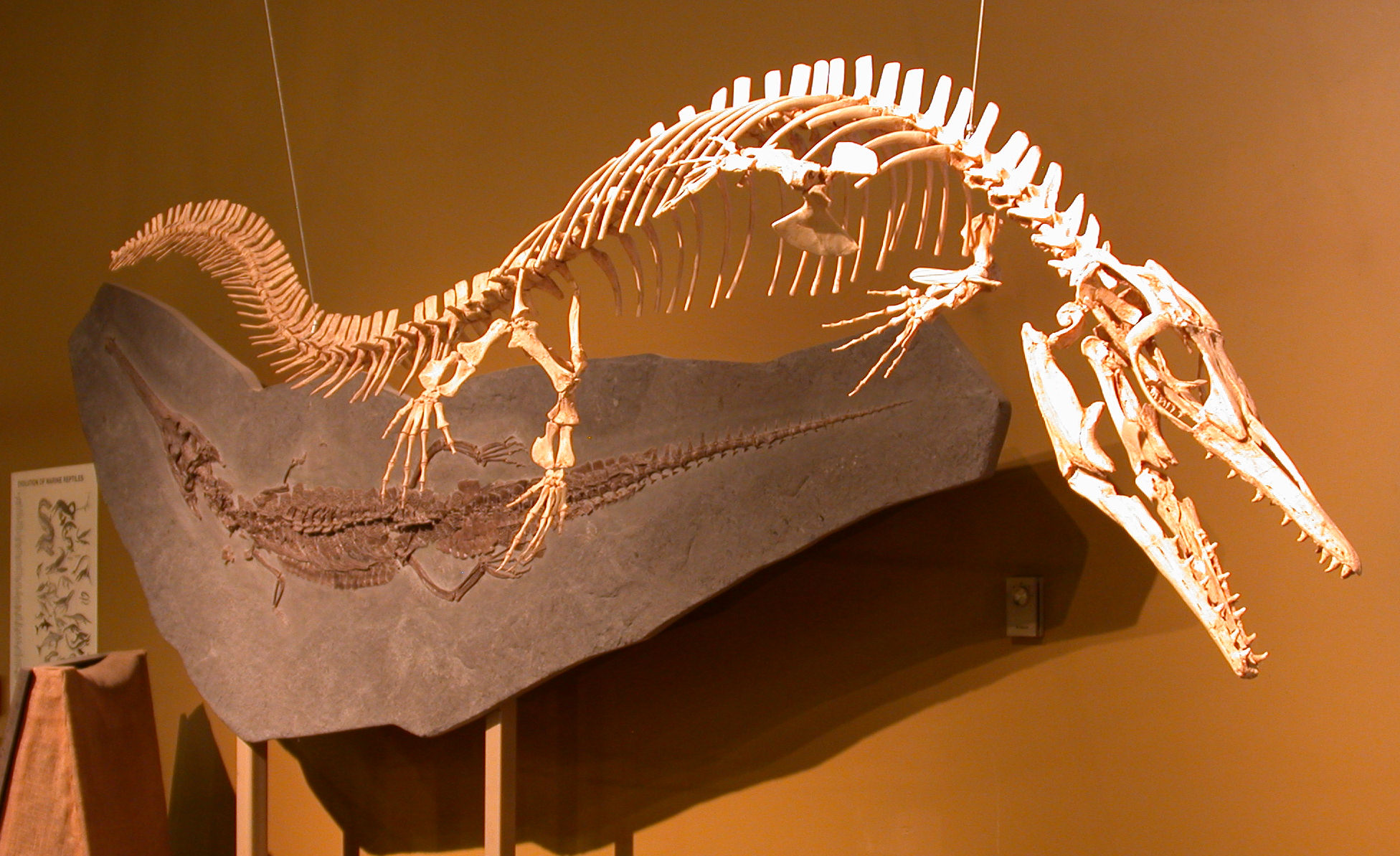

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period, possibly in the Rhaetian stage, about 203 million years ago. They became especially common during the Jurassic Period, thriving until their disappearance due to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 66 million years ago. This gave plesiosaurs an impressive reign of roughly 140 million years in Earth’s oceans.

Mosasaurs, however, were relative newcomers to the marine scene. Mosasaurs were relative latecomers during the span of the Mesozoic. While ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and turtles reigned supreme since the early Triassic, the first mosasaur didn’t emerge until the late Cretaceous, about 99 million years ago. Despite their late arrival, they would prove to be formidable competitors.

Physical Differences and Adaptations

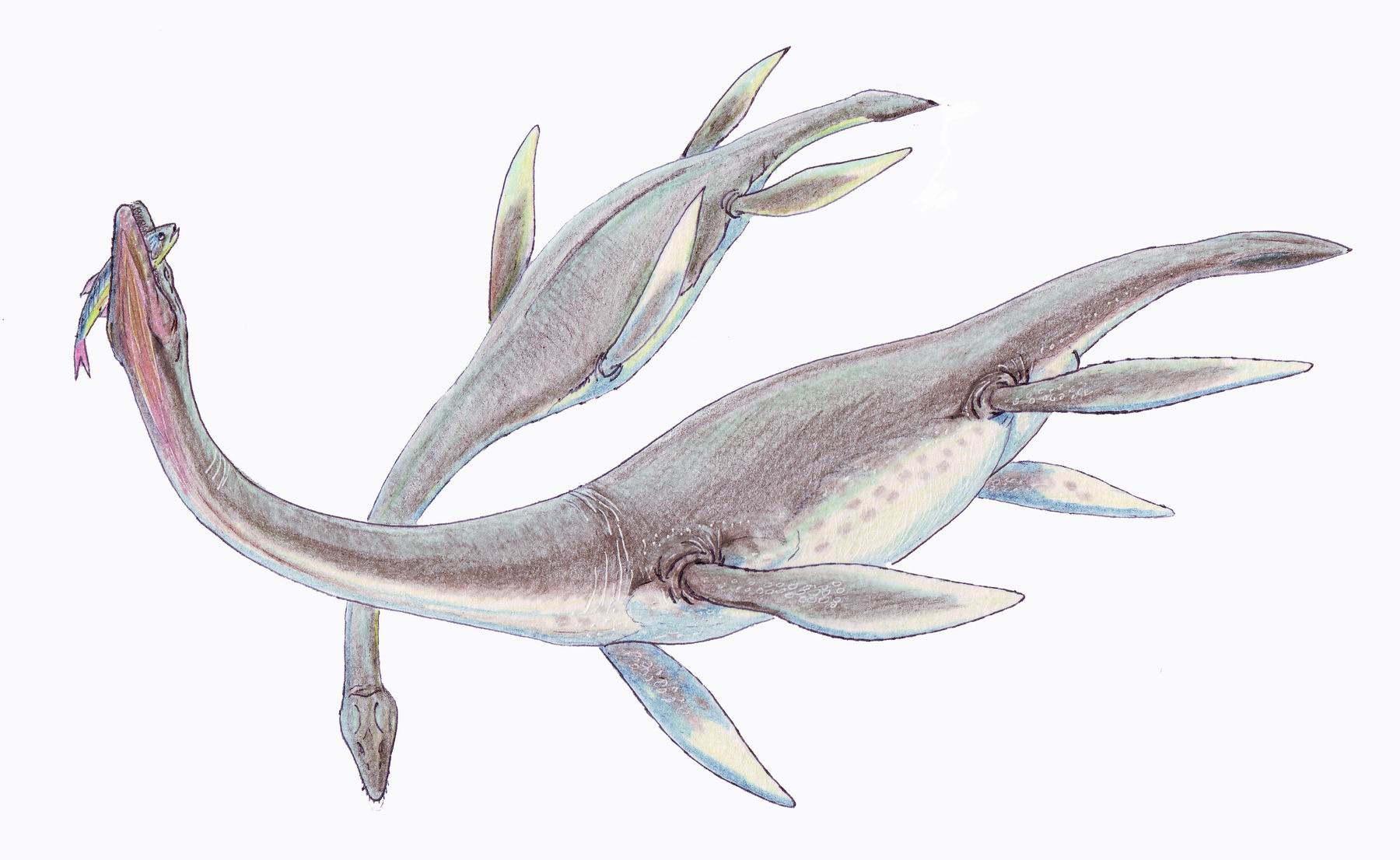

The anatomical differences between these marine giants were striking. The plesiosaur swam with four paddle-like flippers, unlike anything that exists in today’s seas, while mosasaurs had evolved from terrestrial lizards. Mosasaurs swam like crocodiles, swinging their long tails in a back and forth motion. They had goanna-like bodies, pronounced snouts and forked tongues and were covered in a scaly skin.

The swimming mechanics of these creatures revealed their evolutionary origins. This contrasts to the ichthyosaurs and the later mosasaurs, in which the tail provided the main propulsion. Plesiosaurs used their four flippers in coordinated underwater flight, similar to how sea turtles move today, but with all four limbs contributing equally to propulsion.

Body Size and Structure Variations

In general, plesiosaurians varied in adult length from between 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) to about 15 meters (49 ft). The group thus contained some of the largest marine apex predators in the fossil record, roughly equalling the longest ichthyosaurs, mosasaurids, sharks and toothed whales in size. The diversity in size allowed different species to occupy various ecological niches.

Mosasaurs showed similar size diversity. The smallest-known mosasaur was Dallasaurus turneri, which was less than 1 m (3.3 ft) long. Larger mosasaurs were more typical, with many species growing longer than 4 m (13 ft). The largest specimens could rival the biggest plesiosaurs in sheer size and ferocity.

Swimming Speed and Efficiency

One of the most fascinating aspects of this rivalry was the difference in swimming capabilities. She concluded that plesiosaurs were about twenty percent slower than advanced ichthyosaurs, which employed a very effective tunniform movement, oscillating just the tail, but five percent faster than mosasaurids, which were assumed to swim with an inefficient anguilliform, eel-like, movement of the body.

However, this speed advantage came with trade-offs. While the short-necked “pliosauromorphs” (e.g. Liopleurodon) may have been fast swimmers, the long-necked “plesiosauromorphs” were built more for manoeuvrability than for speed, slowed by a strong skin friction, yet capable of a fast rolling movement. Different plesiosaur body types served different hunting strategies.

Dietary Competition and Feeding Strategies

Their diet was unbiased covering anything from ammonites, fish, turtles, plesiosaurs, sea birds and even smaller mosasaurs. This dietary overlap created direct competition between the species, with both groups targeting similar prey resources in their shared marine environments.

Recent research has revealed the intensity of this competition. The teeth of the plesiosaurs and mosasaurs proved to have stable-calcium isotope proportions comparable to those of the superpredators at the very top of today’s marine food web, namely the great white shark. The findings indicate that all the reptiles that vanished at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary were fish-eating top predators in the Maastrichtian marine ecosystem.

The Ichthyosaur Factor

Understanding the rivalry between plesiosaurs and mosasaurs requires acknowledging a third player that shaped their competition. Together, they shared the ocean for approximately 150 million years, however the plesiosaurs outlived the ichthyosaur, spanning the sea, seen in the discovery of their fossils found on each and every continent. The mosasaurs were the last of the sea monsters to dive into the ocean, joining the plesiosaurs within a few million years after the extinction of the ichthyosaurs.

The extinction of ichthyosaurs created new opportunities. Competition with early mosasaurs is unlikely to have been a contributing factor since large mosasaurs did not appear until 3 million years after the ichthyosaur extinction, filling the resulting ecological void left by the extinction of ichthyosaurs. Plesiosaurian polycoltylids perhaps also filled some of the niches previously occupied by ichthyosaurs.

Rise of the Mosasaurs

Uploaded by FunkMonk, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20523418)

The mosasaurs’ success story was remarkable for its speed. Their success proper was due in part to sheer luck. About 92 million years ago, an extinction event occurred that was caused by large-scale underwater volcanic activity. It wiped out several groups of animals in the seas, among these were the ichthyosaurs or “fish lizards”, and the pliosaurs, large-headed and more predatory cousins of the plesiosaurs.

This extinction event opened ecological niches that mosasaurs rapidly filled. But in a short period of time, they quickly diversified. Some developed bulbous teeth that they used to hammer away at oyster-like bivalves, while others developed razor-like teeth that could pierce and shred larger prey, including other mosasaurs. Their rapid adaptation showcased evolutionary flexibility that would serve them well in competition with established plesiosaur populations.

Territorial Competition and Habitat Overlap

The geographic distribution of these marine reptiles reveals extensive overlap in their territories. Mosasaurs are known from every continent including Antarctica. Fossils of mosasaurs have been found on every continent, including Antarctica, indicating they lived throughout the entire globe. Similarly, plesiosaurs had achieved global distribution long before mosasaurs appeared on the scene.

This worldwide overlap meant that competition wasn’t limited to specific regions but was a global phenomenon. Different species adapted to various marine environments, from shallow coastal waters to deeper offshore regions, creating multiple zones of potential conflict between these marine giants.

The Final Chapter

The end of this ancient rivalry came with devastating finality. During the last 20 million years of the Cretaceous period (Turonian–Maastrichtian ages), with the extinction of the ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs, mosasaurids became the dominant marine predators. They themselves became extinct as a result of the K-Pg event at the end of the Cretaceous period, about 66 million years ago.

The vulnerability of these apex predators became clear through their shared feeding strategies. The researchers identify this rivalry between plesiosaurs and mosasaurs as the key to their vulnerability: control of their food web was exercised “bottom-up” in that any scarcity of the limited fish species that these reptiles competed for would jeopardize their survival. This was precisely what occurred at the end of the Cretaceous period when a majority of plankton species disappeared as part of the mass-extinction event. Plankton-eating fish – vital food sources for the plesiosaurs and mosasaurs – also dropped in number, triggering the reptiles’ disappearance.

Conclusion: Legacy of Ancient Rivals

The rivalry between plesiosaurs and mosasaurs represents one of nature’s most dramatic evolutionary competitions. These magnificent marine reptiles ruled the oceans for millions of years, their competition driving innovation and adaptation that would have continued indefinitely under different circumstances. Their story reminds us that even the most successful predators can be vulnerable when their fundamental resources disappear.

The extinction of both groups cleared the way for mammals to eventually colonize marine environments, leading to the whales and dolphins we know today. In many ways, these modern marine mammals have filled the ecological roles once occupied by their ancient reptilian predecessors. The next time you watch dolphins playing in the waves or see footage of great whales in the deep ocean, remember the titans that came before them – the plesiosaurs and mosasaurs who once ruled these same waters with equal majesty and power.

What other evolutionary rivalries might be playing out in today’s oceans that we haven’t yet discovered?