Long before modern crocodilians ruled Earth’s waterways, prehistoric giants dominated ancient ecosystems as apex predators. Among these titans, Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus stand out as two of the most formidable crocodilian ancestors to ever exist. These massive prehistoric reptiles have captured the imagination of paleontologists and the public alike, representing nature’s perfect predatory design scaled to terrifying proportions. Though separated by time and geography, comparing these ancient behemoths reveals fascinating insights into convergent evolution, prehistoric ecosystems, and the ultimate limits of crocodilian size and power. This article explores the similarities and differences between these two prehistoric giants, examining how they lived, hunted, and ruled their respective domains millions of years ago.

Origins and Evolutionary Context

Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus evolved from different lineages of crocodiliform archosaurs, showcasing remarkable examples of convergent evolution. Sarcosuchus imperator, often called “SuperCroc,” belonged to the Pholidosauridae family and lived approximately 112 to 95 million years ago during the mid-Cretaceous period, primarily in what is now Africa and South America. Deinosuchus, meaning “terrible crocodile,” emerged later in the Late Cretaceous period (approximately 82 to 73 million years ago) in North America and was more closely related to modern alligators and caimans as a member of Alligatoroidea. These creatures evolved separately, adapting to similar ecological niches in their respective environments, which resulted in comparable body plans despite their distinct evolutionary histories. Their existence demonstrates how the crocodilian body plan proved remarkably successful across different continents and time periods, with minimal modifications needed over millions of years.

Size Comparison: The Battle of the Giants

When discussing these prehistoric titans, size inevitably becomes the most striking point of comparison. Sarcosuchus stands as potentially the larger of the two, with estimates suggesting it reached lengths of up to 11-12 meters (36-40 feet) and weighed approximately 8-10 metric tons. Its skull alone measured nearly 1.8 meters (6 feet), housing powerful jaws lined with over 100 teeth. Deinosuchus, while slightly smaller, was no less impressive, reaching estimated lengths of 10-12 meters (33-39 feet) and weighing between 5-10 metric tons. For comparison, the largest modern crocodilian, the saltwater crocodile, typically maxes out at around 6 meters (20 feet) and 1 ton. The sheer scale of these prehistoric creatures dwarfs their modern descendants, making them among the largest crocodiliform reptiles to ever exist. Their massive size represented an evolutionary adaptation that allowed them to prey upon even the largest dinosaurs that shared their environments.

Skull Morphology and Bite Force

The skulls of these ancient predators reveal crucial differences in hunting strategies and prey preferences. Sarcosuchus possessed a relatively long, narrow snout (similar to modern gharials) that was slightly expanded at the end into a bulbous structure called a bulla, which may have housed enhanced sensory organs for detecting prey movements in water. This elongated snout suggests specialization for catching fish, though it was robust enough to capture larger prey as well. Deinosuchus, conversely, had a broader, more alligator-like skull built for crushing power rather than speed, indicating it was adapted for ambushing and overpowering large dinosaurs at the water’s edge. Bite force estimates for both creatures are staggering, with some research suggesting Deinosuchus may have had a bite force exceeding 23,000 pounds – powerful enough to crush dinosaur bones. These different skull adaptations highlight how these giants evolved specialized feeding strategies despite their superficial similarities.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

The two giant crocodilians occupied different continents during their reign, which significantly influenced their evolution and behavior. Sarcosuchus fossils have been discovered primarily in the Sahara Desert of Niger and parts of Brazil, indicating it thrived in the lush, river systems that once flowed through these now-arid regions during the mid-Cretaceous period. These waterways were part of a massive river system that existed when Africa and South America were still connected or recently separated. Deinosuchus, meanwhile, dominated coastal swamps and estuaries along the eastern and southern regions of what is now the United States, with significant fossil discoveries in Texas, New Jersey, and North Carolina. It lived in a warm, subtropical environment along the shores of the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow sea that divided North America. These different geographical contexts meant each species evolved in response to distinct ecological pressures and prey availability, resulting in their specialized adaptations.

Hunting Strategies and Prey Selection

The hunting strategies of these prehistoric crocodilians likely resembled those of modern species, but on a far more terrifying scale. Sarcosuchus, with its more gharial-like snout, was likely a proficient fish hunter that could also tackle larger prey when opportunity arose. Paleontologists believe it employed the classic crocodilian ambush strategy – lying submerged with only its eyes and nostrils visible before lunging with explosive speed to capture prey. Evidence suggests it may have fed on large fish, turtles, and even small to medium-sized dinosaurs. Deinosuchus, meanwhile, appears to have been specialized for tackling much larger prey, including dinosaurs. Fossil evidence, including dinosaur bones bearing distinctive Deinosuchus tooth marks, indicates it actively preyed upon hadrosaurids (duck-billed dinosaurs) and possibly even tyrannosaurs that came to the water’s edge. Both predators likely employed the infamous “death roll” technique to dismember large prey, using their massive body weight and powerful jaws to devastating effect.

Armor and Defense Mechanisms

Both Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus boasted impressive natural armor that made them nearly invulnerable to predators. Sarcosuchus featured especially thick osteoderms (bony plates) embedded in its skin, forming an interlocking shield across its back and neck. These osteoderms were particularly massive and featured deep pitting, likely to accommodate blood vessels for thermoregulation in the hot Cretaceous climate. Deinosuchus similarly possessed robust body armor, with its osteoderms featuring distinctive raised ridges that created a more textured appearance. The armor of both species served multiple functions: protection from potential predators or rival crocodilians, structural support for their massive bodies, and possibly thermoregulation by absorbing and releasing heat. Additionally, both likely had the thick, tough hide characteristic of modern crocodilians, providing further protection and reducing water loss in their semi-aquatic lifestyles.

Growth Patterns and Lifespan

Understanding the growth patterns of these prehistoric giants provides insight into their remarkable size. Like modern crocodilians, both Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus likely experienced indeterminate growth – continuing to grow throughout their lives, albeit at a decreasing rate with age. Research on growth rings in fossilized osteoderms suggests Sarcosuchus may have taken 50-60 years to reach its maximum size, with potential lifespans extending to 80-100 years. Similar studies indicate Deinosuchus may have grown at a comparable rate, reaching adult size after several decades. This slow, continuous growth pattern allowed these creatures to achieve their enormous proportions, surpassing the size constraints that limit most vertebrates. Interestingly, both genera likely experienced different growth phases, with rapid juvenile growth followed by slower growth during sexual maturity, similar to patterns observed in modern crocodilians but extended over much longer timeframes due to their exceptional size.

Ecological Impact as Apex Predators

As apex predators in their respective ecosystems, Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus exerted enormous influence on their environments. Sarcosuchus would have controlled populations of fish and smaller reptiles while occasionally taking dinosaurs, helping to maintain ecosystem balance in the river systems of ancient Africa and South America. By removing weak or injured animals, it likely contributed to the overall health of prey populations. Deinosuchus played an even more dramatic ecological role by being one of the few predators capable of taking down fully-grown dinosaurs, creating unique predator-prey dynamics along ancient North American coastlines. Evidence suggests dinosaurs may have altered their behavior to avoid water edges during certain times or seasons to reduce predation risk. Both prehistoric crocodilians also likely influenced prey evolution, potentially driving selection for increased vigilance, different migration patterns, or other anti-predator adaptations in the animals they hunted.

Reproduction and Parental Care

The reproductive strategies of Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus can be inferred from studying their modern relatives and fossil evidence. Like all crocodilians, they were egg-layers, with females likely excavating nests along riverbanks or shorelines to deposit their clutches. Given their enormous size, mature females may have produced exceptionally large clutches of eggs – potentially numbering in the dozens – to offset high mortality rates among hatchlings. Maternal protection was likely a crucial aspect of their reproductive strategy, with female Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus guarding their nests against egg predators during the incubation period. After hatching, young may have benefited from some degree of parental protection, though juvenile mortality would still have been high due to predation from other aquatic predators and even cannibalism from adults. The journey from hatchling to massive adult would have been a perilous one, with perhaps only a small percentage surviving to reproductive age.

Extinction and Ecological Succession

The reign of these titanic crocodilians eventually came to an end due to a combination of environmental changes and ecological pressures. Sarcosuchus disappeared from the fossil record around 95 million years ago, well before the end-Cretaceous mass extinction that claimed the non-avian dinosaurs. Its extinction may have been related to changing river systems in Africa and South America as the continents continued to drift apart, along with competition from emerging crocodilian species better adapted to new ecological conditions. Deinosuchus met its end approximately 73 million years ago, also before the K-Pg extinction event, possibly due to cooling climates and habitat loss as the Western Interior Seaway began to recede. Neither species left direct descendants, though their ecological niches were eventually filled by smaller, more specialized crocodilian species that continue to thrive today. Their disappearance marked the end of the era of truly giant crocodilians, as no subsequent species has matched their tremendous proportions.

Scientific Discoveries and Fossil Record

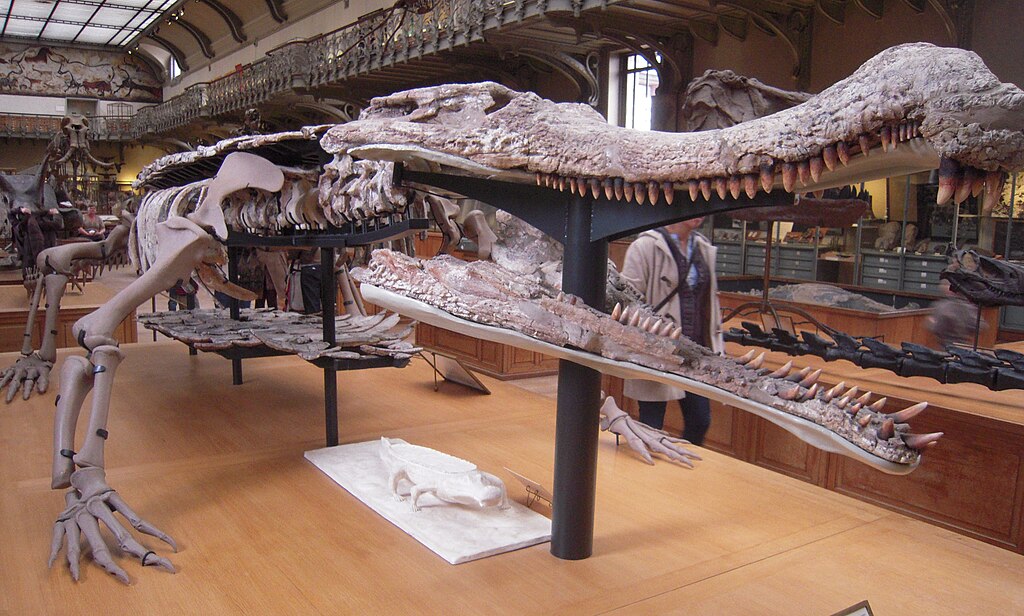

The story of how these prehistoric giants were discovered and studied reflects the fascinating progression of paleontological knowledge. Sarcosuchus was first described scientifically in the 1960s based on fragmentary remains from Niger, but it wasn’t until Paul Sereno’s expeditions in the 1990s and early 2000s that more complete specimens were discovered, allowing for accurate size and anatomical reconstructions. These discoveries in the Tenere Desert of Niger included a nearly complete skull and substantial postcranial material that revolutionized our understanding of this creature. Deinosuchus has a longer history in scientific literature, first described in 1909, with numerous specimens discovered across the southern United States over the following century. Particularly notable findings include massive teeth (some exceeding 5 inches in length) and jaw fragments that helped establish its fearsome reputation. Both creatures continue to attract scientific interest, with new analytical techniques providing ever more detailed insights into their biology, behavior, and evolutionary significance.

Cultural Impact and Representations

These prehistoric giants have captured the public imagination and become icons of prehistoric life alongside dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex. Sarcosuchus achieved widespread recognition following National Geographic’s “SuperCroc” documentary and exhibition in the early 2000s, which featured life-sized reconstructions that stunned viewers with their scale. The creature has since appeared in numerous documentaries, books, and video games, including the popular “Ark: Survival Evolved.” Deinosuchus has similarly penetrated popular culture, appearing in documentary series like “Prehistoric Planet” and various paleoart reconstructions that emphasize its dinosaur-hunting capabilities. Museums around the world showcase reconstructions of both creatures, with their massive skulls serving as particularly impressive display pieces. Their enduring popularity stems partly from their familiar yet alien nature – recognizable as crocodilians but scaled to such extreme proportions that they seem almost mythological, providing a tangible connection to Earth’s prehistoric past.

Modern Research and Ongoing Discoveries

Scientific understanding of these ancient predators continues to evolve with new research methods and fossil discoveries. Recent studies utilizing CT scans and digital reconstructions have provided insights into the brain morphology and sensory capabilities of Sarcosuchus, suggesting enhanced olfactory abilities that may have aided in hunting. Researchers have also conducted biomechanical analyses of jaw structures to better understand feeding mechanics and bite force capabilities. For Deinosuchus, new discoveries of bite marks on dinosaur fossils continue to illuminate predator-prey relationships in Late Cretaceous ecosystems. Growth studies examining bone histology have refined our understanding of how these creatures achieved their enormous size, with implications for understanding the upper limits of reptilian growth. Ongoing excavations, particularly in previously unexplored regions of Africa and South America, may yet yield new Sarcosuchus specimens, while continued exploration of Cretaceous coastal deposits in North America promises further Deinosuchus discoveries that could expand our knowledge of these magnificent prehistoric predators.

Conclusion: Legacy of the Giant Crocodilians

The comparative study of Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus offers a fascinating window into convergent evolution and the apex of crocodilian development. Despite evolving independently on different continents, these creatures achieved similar massive proportions and occupied comparable ecological niches as dominant semi-aquatic predators. Their success demonstrates the remarkable effectiveness of the crocodilian body plan – so efficient that it has remained largely unchanged for over 200 million years, with these giants representing its ultimate expression in terms of size and predatory power. Though neither Sarcosuchus nor Deinosuchus survived to the present day, their legacy lives on in the crocodiles and alligators that continue to inhabit our planet’s waterways. Modern crocodilians, while smaller, retain the same basic adaptations that made their colossal ancestors such successful predators. By studying these prehistoric giants, scientists gain valuable insights not only into past ecosystems but also into the evolutionary processes that shape life on Earth and the extraordinary adaptability of one of nature’s most perfect predatory designs.