In the scorching landscapes of what is now Arizona, approximately 220 million years ago during the Late Triassic period, a massive crocodile-like predator ruled the waterways. Smilosuchus, whose name translates to “knife crocodile,” was one of the largest and most fearsome phytosaurs—distant relatives of today’s crocodilians. Armed with saber-like teeth and reaching lengths of up to 40 feet, these impressive reptiles dominated their ecosystem long before dinosaurs rose to prominence. Their fossil remains offer paleontologists crucial insights into the complex predator-prey relationships of Triassic river systems and the evolutionary history of archosaurs.

The Discovery and Naming of Smilosuchus

The story of Smilosuchus begins in the late 19th century when fossil hunters exploring the rich paleontological sites of Arizona’s Chinle Formation uncovered large, crocodile-like skulls with distinctive features. Initially classified under various names, including Leptosuchus and Machaeroprosopus, these fossils were later reorganized under the genus Smilosuchus in 1995 by paleontologists Long and Murry. The name derives from Greek words “smilo” (knife or blade) and “suchus” (crocodile), referencing the animal’s blade-like teeth and superficial resemblance to modern crocodilians. The type species, Smilosuchus gregorii, was named in honor of American paleontologist William K. Gregory, who contributed significantly to the early understanding of these prehistoric reptiles. The discovery of numerous Smilosuchus specimens has made the Chinle Formation one of the most important sites for understanding Late Triassic ecosystems in North America.

Taxonomic Classification and Evolutionary Relationships

Smilosuchus belongs to the order Phytosauria, a group of crocodile-like reptiles that were not direct ancestors of modern crocodilians but rather represent a remarkable case of convergent evolution. Within the archosaur family tree, phytosaurs sit as cousins to the lineage that would eventually produce crocodiles and dinosaurs (including birds). Specifically, Smilosuchus is classified within the family Phytosauridae and subfamily Pseudopalatinae, characterized by their robust skulls and heterodont dentition. Paleontologists recognize several species within the genus, including S. gregorii, S. adamanensis, and S. lithodendrorum, each showing subtle variations in skull morphology and size. Understanding Smilosuchus’s place in the evolutionary landscape provides vital insights into the diversification of archosaurs during a critical period of Earth’s history, just before the end-Triassic extinction event that would reshape life on our planet.

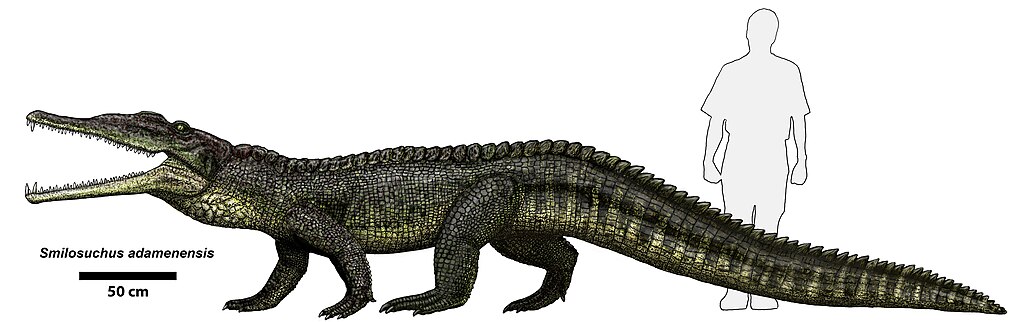

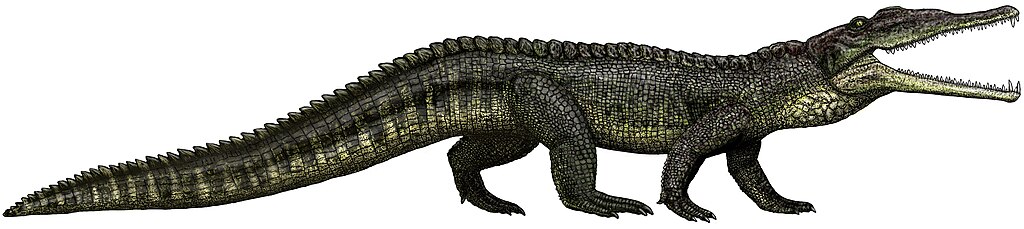

Physical Characteristics and Size

Smilosuchus was a truly imposing predator, with the largest specimens reaching estimated lengths of 35-40 feet—dimensions that rival or exceed those of the largest modern crocodilians. Its body followed the classic phytosaur blueprint: a long, heavily armored body with four powerful limbs and a massive, elongated skull measuring up to 5 feet in length. Unlike modern crocodilians, Smilosuchus and other phytosaurs had nostrils positioned high on their snouts, near their eyes, rather than at the tip—an adaptation possibly allowing them to breathe while remaining mostly submerged. Their bodies were covered in bony scutes (osteoderms) providing protection and possibly thermoregulatory benefits. Sexual dimorphism was likely present in Smilosuchus, with males potentially possessing larger crests on their snouts and overall more robust proportions than females, though this remains somewhat speculative based on the fossil evidence currently available.

The Fearsome Dentition

The most striking feature of Smilosuchus, and the inspiration for its knife-like name, was its impressive dental arsenal. Unlike the relatively uniform teeth of modern crocodilians, Smilosuchus possessed heterodont dentition—different types of teeth specialized for different functions. At the front of its elongated jaws sat numerous conical teeth perfect for seizing prey, while farther back were larger, blade-like teeth with serrated edges capable of slicing through flesh and bone. Some of these teeth could reach lengths of several inches and featured the curved, compressed shape reminiscent of saber-toothed predatory mammals that would evolve millions of years later. This sophisticated dental arrangement allowed Smilosuchus to process a wide variety of prey items, from fish to large terrestrial animals that came to the water’s edge. Tooth replacement occurred continuously throughout its life, similar to modern sharks and crocodilians, ensuring this apex predator always maintained its lethal bite force.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Smilosuchus inhabited the lush river systems that flowed through what is now the southwestern United States during the Late Triassic period. Most fossils come from Arizona’s Chinle Formation, a geological unit representing ancient floodplains, rivers, and lakes that existed approximately 220-205 million years ago. During this time, the region experienced a monsoonal climate, with alternating wet and dry seasons creating dynamic riparian environments. These waterways supported diverse ecosystems, with dense vegetation along the banks and numerous prey species that would have sustained large predators like Smilosuchus. While most abundant in Arizona, related specimens have been discovered across the American Southwest, suggesting these massive phytosaurs had a considerable geographic range throughout the region. The concentration of fossils in ancient river deposits indicates these animals were primarily aquatic, though they likely patrolled both water bodies and adjacent shorelines in search of prey.

Hunting and Feeding Behavior

As the dominant predator of its ecosystem, Smilosuchus employed hunting strategies similar to modern crocodilians but with adaptations unique to phytosaurs. Its elongated jaws and powerful neck muscles enabled lightning-fast strikes from an ambush position, likely lurking mostly submerged with only its eyes and elevated nostrils exposed above the water’s surface. The positioning of its nostrils allowed Smilosuchus to breathe while keeping the rest of its body hidden, providing a significant advantage when stalking prey coming to drink at the water’s edge. Once prey was seized with its formidable anterior teeth, Smilosuchus would use its powerful jaws to drag the victim into deeper water, employing the “death roll” technique still used by modern crocodilians to dismember larger prey. Analysis of Smilosuchus teeth shows wear patterns consistent with a varied diet that may have included fish, amphibians, and terrestrial reptiles, including early dinosaurs and their relatives. As an opportunistic apex predator, Smilosuchus likely scavenged when necessary, taking advantage of any available food sources in its environment.

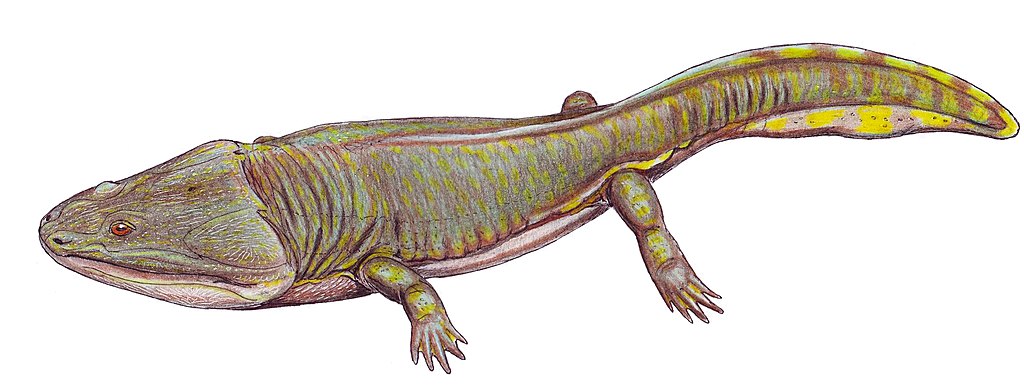

Ecological Role and Predator-Prey Relationships

Smilosuchus occupied the apex predator niche in Late Triassic freshwater ecosystems, serving as a crucial regulator of prey populations and influencing the behavior and evolution of contemporary species. By controlling populations of herbivores and smaller carnivores, these massive phytosaurs helped maintain the balance of their ecosystem, preventing any single species from dominating resources. The fossil record suggests Smilosuchus preyed upon various animals, including large amphibians like metoposaurs, primitive reptiles, early dinosaurs, and potentially even other phytosaurs in cases of cannibalism. Contemporary predators that might have competed with Smilosuchus included rauisuchians and other large archosaurs, though the semi-aquatic lifestyle of phytosaurs likely reduced direct competition through niche partitioning. The presence of such a formidable predator would have exerted strong selective pressure on prey species, potentially driving evolutionary adaptations like increased vigilance, defensive structures, or avoidance of waterways—ecological relationships that shaped the trajectory of animal evolution during this critical period.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

While direct evidence of Smilosuchus reproduction remains limited, paleontologists can make educated inferences based on both the fossil record and comparisons with modern archosaurs. Like other phytosaurs, Smilosuchus likely laid eggs in nests constructed on riverbanks or sandy areas adjacent to water, similar to modern crocodilians. Clutch sizes were probably substantial, as high mortality rates among hatchlings would necessitate numerous offspring to ensure survival of the species. Young Smilosuchus would have been vulnerable to predation from various sources, including larger members of their own species, leading to a high attrition rate in the early life stages. Growth was likely rapid during the juvenile phase, slowing as individuals approached sexual maturity. Based on growth ring analysis of related phytosaurs, scientists estimate that Smilosuchus may have lived 30-50 years in optimal conditions, gradually increasing in size throughout its life. Sexual dimorphism, particularly in cranial features, suggests complex social and reproductive behaviors that may have included territorial disputes and elaborate mating rituals.

Smilosuchus in the Triassic Ecosystem

The Late Triassic period represented a crucial transitional time in Earth’s history, with ecosystems recovering from the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event and new groups of animals diversifying to fill available niches. Within this dynamic landscape, Smilosuchus reigned as one of the most formidable predators in what is now the American Southwest. The Chinle Formation ecosystem where Smilosuchus thrived included a diverse assemblage of animals: primitive conifers and ferns dominated the flora, while the fauna featured early dinosaurs, large amphibians, various reptiles, and distant relatives of mammals. Rivers and lakes formed the central arteries of this environment, with seasonal flooding creating rich floodplains that supported abundant plant and animal life. As an apex predator specializing in the aquatic-terrestrial interface, Smilosuchus occupied a critical position in the food web, influencing the behavior and evolution of numerous other species through predation pressure. The fossil record indicates that multiple phytosaur species sometimes inhabited the same waterways, suggesting potential resource partitioning or specialized feeding strategies to reduce direct competition.

Extinction and Legacy

Despite their evolutionary success and dominance throughout the Late Triassic, Smilosuchus and all other phytosaurs disappeared from the fossil record at the end-Triassic extinction event approximately 201 million years ago. This major extinction episode, potentially triggered by massive volcanic eruptions associated with the breakup of Pangaea, eliminated roughly 75-80% of all species on Earth. The disappearance of phytosaurs created a vacant ecological niche that would eventually be filled by true crocodilians, which evolved similar body plans through convergent evolution. Though Smilosuchus left no direct descendants, its evolutionary legacy lives on in the extensive fossil record it left behind, particularly in the Chinle Formation. These fossils provide paleontologists with critical information about Triassic ecosystems, predator-prey dynamics, and the evolutionary history of archosaurs. The study of Smilosuchus and its relatives offers valuable insights into how climate change and geological events influence the rise and fall of dominant species—lessons with relevance to understanding modern biodiversity patterns and extinction threats.

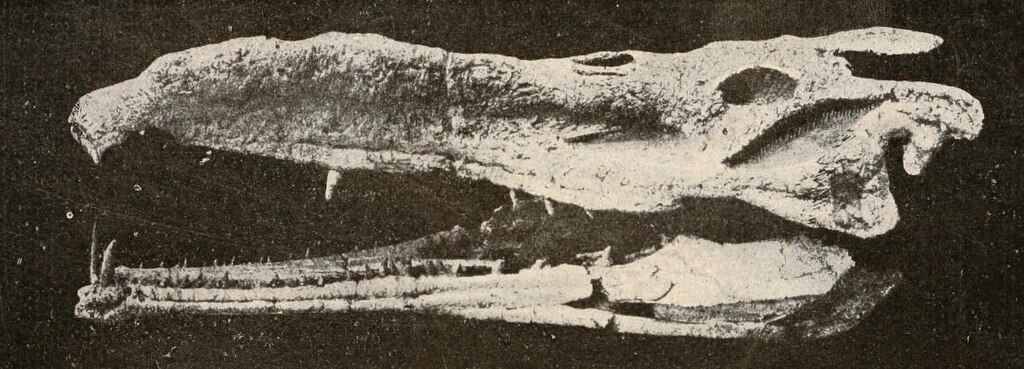

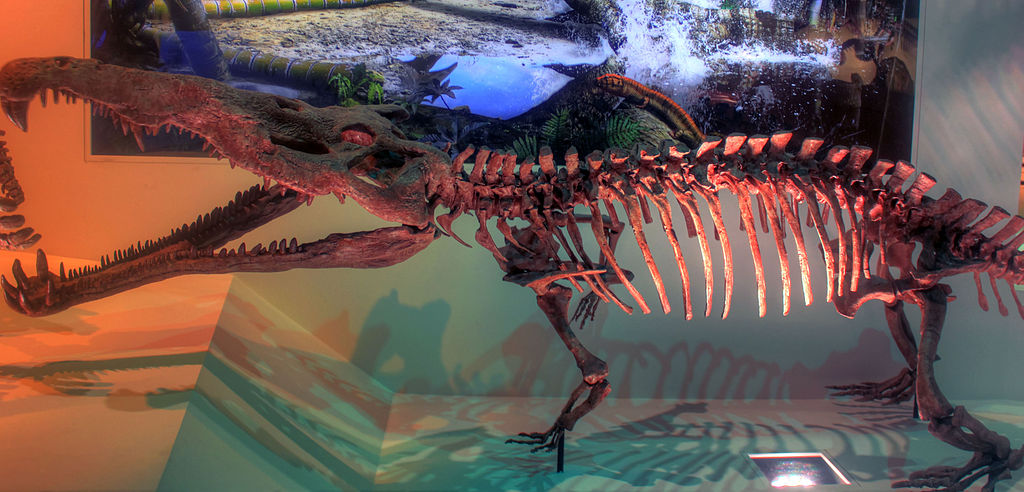

Notable Fossil Discoveries

Several particularly significant Smilosuchus specimens have enhanced our understanding of this formidable predator. The Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona stands as one of the most productive sites for Smilosuchus fossils, with numerous skulls and partial skeletons recovered since systematic excavations began in the early 20th century. One noteworthy specimen, discovered in the Blue Mesa member of the Chinle Formation in the 1980s, included an exceptionally well-preserved skull exceeding 1.5 meters in length, providing detailed insights into the cranial anatomy and sensory capabilities of these animals. Another remarkable find from Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, revealed evidence of potential predator-prey interactions, with Smilosuchus remains found in association with those of early dinosaurs and other contemporary reptiles. The University of California Museum of Paleontology houses several important Smilosuchus specimens, including articulated vertebral columns showing the transition from neck to tail vertebrae and revealing details about locomotion and muscle attachment. Each new discovery adds to our understanding of these magnificent creatures, with ongoing fieldwork in the American Southwest continuing to yield valuable specimens that refine our knowledge of phytosaur diversity and ecology.

Scientific Significance and Research

Smilosuchus occupies a significant position in paleontological research for multiple reasons that extend beyond its impressive size and predatory adaptations. As one of the most completely known phytosaurs, it serves as a reference point for understanding the evolution and diversity of this important archosaur group. Studies of Smilosuchus have contributed substantially to our understanding of Late Triassic paleoecology, helping scientists reconstruct food webs and environmental conditions in prehistoric North America. The exceptional preservation of some specimens has allowed researchers to employ advanced techniques like CT scanning to examine internal cranial structures, revealing details about brain size, sensory capabilities, and feeding mechanics. Ongoing research focuses on several aspects of Smilosuchus biology, including growth patterns as revealed through bone histology, biomechanical analyses of bite force and skull strength, and refined taxonomic assessments using geometric morphometrics to better distinguish between species. Additionally, Smilosuchus serves as an important case study in convergent evolution, demonstrating how similar selective pressures can produce comparable adaptations in unrelated lineages—a phenomenon seen in the remarkable similarities between phytosaurs and modern crocodilians despite their distant relationship.

Smilosuchus in Popular Culture

While not achieving the celebrity status of dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus or Velociraptor, Smilosuchus has nevertheless made appearances in scientific documentaries and educational media focused on prehistoric life. The BBC documentary “Walking with Monsters” featured phytosaurs similar to Smilosuchus, introducing these impressive creatures to a wider audience and highlighting their importance in Triassic ecosystems. Several natural history museums across the United States showcase Smilosuchus reconstructions in their Mesozoic exhibits, with particularly notable displays at the Petrified Forest National Park visitor center and the Museum of Northern Arizona. Educational programs in paleontology frequently use Smilosuchus as an example when discussing convergent evolution, predator adaptations, and the diversity of archosaurs before the age of dinosaurs. Though less commercially exploited than many dinosaurs, Smilosuchus has inspired paleoartists who strive to create accurate reconstructions of these ancient predators, contributing to our visual understanding of creatures known primarily through their fossilized remains. As public interest in prehistoric life beyond dinosaurs continues to grow, Smilosuchus stands poised to gain greater recognition as one of North America’s most impressive prehistoric predators.

Conclusion

Smilosuchus represents a fascinating chapter in Earth’s evolutionary history—a dominant predator that ruled the waterways of ancient Arizona long before the rise of dinosaurs. With its massive size, specialized dentition, and sophisticated hunting adaptations, this “knife crocodile” exemplified the remarkable diversity of archosaurs during the Late Triassic period. Though extinct for over 200 million years, Smilosuchus continues to provide valuable scientific insights into predator-prey dynamics, convergent evolution, and ecosystem functioning. As paleontologists continue their work in the fossil-rich deposits of the American Southwest, our understanding of these magnificent creatures grows ever more detailed, allowing us to better appreciate the complex and fascinating world that existed so long before our own.