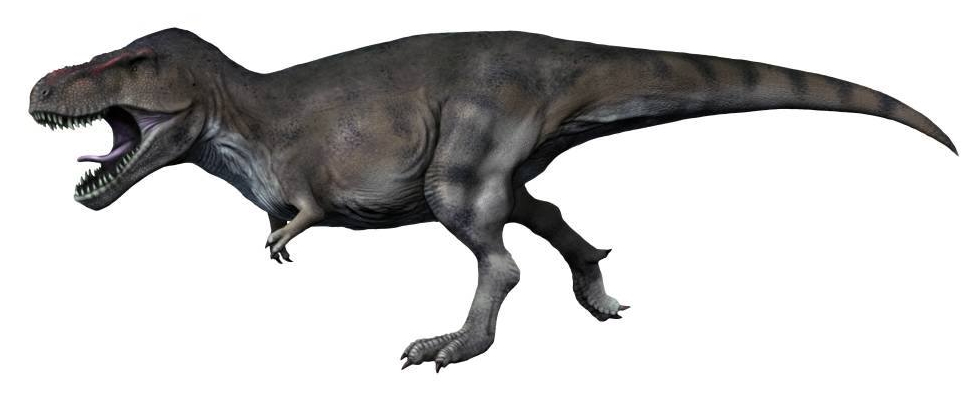

The Tyrannosaurus rex has captured human imagination like few other prehistoric creatures. Standing at up to 40 feet long with bone-crushing jaws and massive hind limbs, this Late Cretaceous dinosaur has long been portrayed as the ultimate predator in popular culture. However, a scientific debate has raged for decades: was T. rex primarily a ferocious hunter or an opportunistic scavenger? Recent fossil discoveries from the Hell Creek Formation in Montana have provided tantalizing new evidence that may help resolve this long-standing controversy. These findings are reshaping our understanding of T. rex’s ecological role and hunting behaviors in the ancient landscapes of North America approximately 68-66 million years ago.

The Historical Debate: Hunter or Scavenger?

The question of T. rex’s feeding behavior first gained serious scientific attention in the 1990s when paleontologist Jack Horner proposed that the dinosaur might have been primarily a scavenger rather than an active predator. His arguments centered on T. rex’s seemingly disproportionate features: tiny forelimbs that appeared useless in hunting, powerful olfactory bulbs suggesting a keen sense of smell for detecting carrion, and robust jaws perfect for crushing bones of already-dead animals. This controversial hypothesis challenged the popular image of T. rex as the ultimate predator and ignited a fierce debate within paleontological circles. Other scientists countered that T. rex’s forward-facing eyes suggested depth perception, powerful legs indicated speed, and massive size all pointed toward predatory behavior. This fundamental question about T. rex’s lifestyle has persisted for decades, with new fossil evidence continually adding nuance to the discussion.

Montana’s Hell Creek Formation: A T. rex Treasure Trove

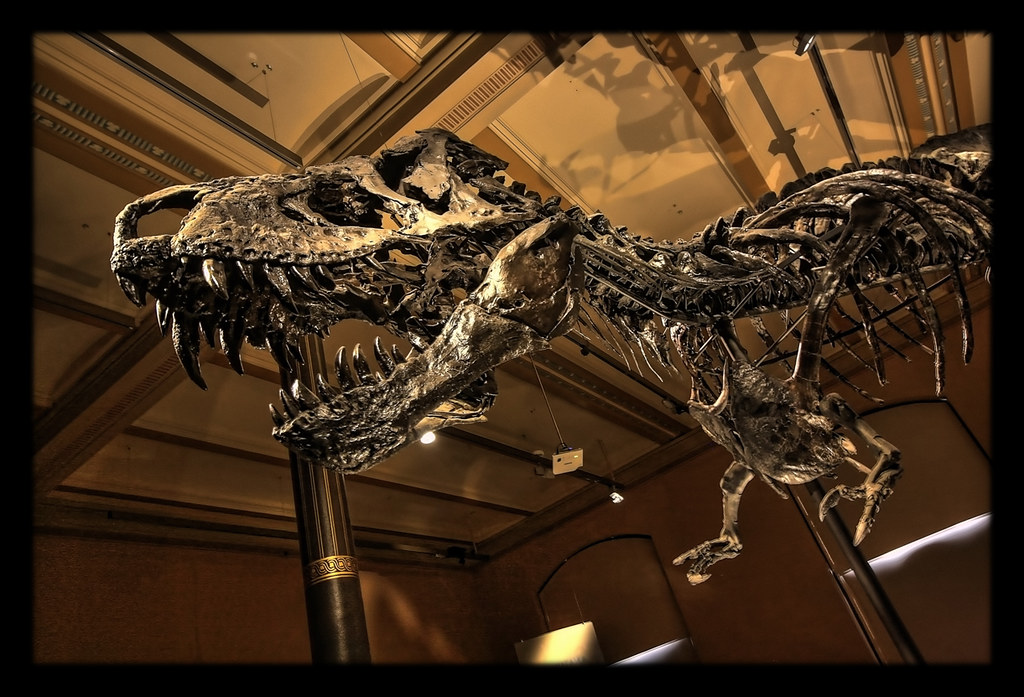

The Hell Creek Formation spans parts of Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming, representing one of the richest dinosaur fossil beds in the world. This geological formation has yielded some of the most complete and well-preserved T. rex specimens ever discovered, including the famous “Sue” and “Stan” specimens. Montana’s portion of Hell Creek has been particularly prolific, with multiple T. rex fossils discovered innearbysuggesting this region was once prime T. rex territory. The formation represents the last few million years of the Cretaceous period, immediately before the extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs, providing a crucial window into T. rex’s ecological role during this pivotal time. The exceptional preservation conditions in these ancient river valleys and floodplains have allowed scientists to gather unprecedented data about T. rex anatomy, population density, and potentially, feeding behaviors.

Bite Force Evidence: Built for Bone Crushing

Fossil evidence from Montana specimens has allowed scientists to estimate T. rex’s bite force with remarkable precision. Using computer models and comparative anatomy, researchers have calculated that T. rex could exert a bite force of approximately 8,000 pounds, making it the strongest bite of any terrestrial animal ever known. This extraordinary force would have easily crushed through bone, as evidenced by distinctive bite marks found on prey fossils and “bone fragments” in fossilized T. rex feces (coprolites) discovered in Montana. The dinosaur’s teeth were designed not just for slicing flesh but for crushing bone, allowing it to access nutritious bone marrow. This extreme specialization suggests T. rex was adapted to extract maximum nutrition from carcasses, whether it killed the prey itself or scavenged it. The combination of serrated teeth for cutting and robust rear teeth for crushing indicates a versatile feeding apparatus that could handle both fresh kills and days-old carcasses.

Growth Patterns and Metabolic Needs

Analysis of growth rings in T. rex bones from Montana has revealed fascinating details about the dinosaur’s growth rate and metabolic demands. Studies show that T. rex experienced a remarkable growth spurt during adolescence, gaining up to 1,500 pounds per year during its teenage years. This rapid growth suggests a metabolism more similar to modern birds than to reptiles, requiring substantial caloric intake. Scientists estimate that an adult T. rex would need to consume hundreds of pounds of meat regularly to sustain its massive body. Such enormous caloric requirements would make pure scavenging challenging, as finding sufficient carrion in a prehistoric ecosystem would be unpredictable. The metabolic evidence, therefore, suggests that T. rex likely couldn’t afford to be exclusively a scavenger and would need to actively hunt at least some of the time to meet its energy needs, particularly during its rapid growth phases.

Predation Evidence: The Smoking Gun

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for T. rex’s predatory behavior comes from fossilized prey animals showing signs of attack and healing. Several hadrosaur and ceratopsian fossils from Montana exhibit T. rex tooth marks with signs of healing, indicating the animals survived the initial attack. One famous Triceratops specimen dubbed “Murray” shows T. rex bite marks on its frill and healed injuries consistent with a failed predation attempt. These “smoking gun” fossils provide direct evidence that T. rex actively hunted living prey, not just scavenged already-dead animals. Additionally, the Hell Creek Formation has yielded fossils showing evidence of pursuit and struggle between T. rex and its prey, including specimens where predator and prey were preserved together in positions suggesting active hunting behavior. These rare but significant findings strongly support the hypothesis that T. rex was indeed an active predator, at least some of the time.

Speed and Agility: The Locomotion Question

The question of how fast T. rex could move has direct implications for understanding its hunting capabilities. Recent biomechanical studies of Montana specimens have revised earlier assumptions about T. rex’s speed. While earlier estimates suggested speeds of up to 45 mph, current research using muscle attachment sites, bone strength analyses, and computer modeling indicates a more modest but still impressive top speed of 10-25 mph. This speed would have made T. rex faster than many of its potential prey species, including Triceratops and Edmontosaurus. The dinosaur’s massive leg muscles and reinforced skeleton suggest it was built for powerful, sustained pursuit rather than rapid acceleration. Interestingly, juvenile T. rex specimens show proportionally longer legs and lighter builds, suggesting younger individuals may have been more agile hunters than adults, potentially indicating a shift in hunting strategies throughout the dinosaur’s lifespan.

Social Behavior: Lone Hunter or Pack Predator?

The discovery of multiple T. rex specimens nearby in Montana has sparked debate about whether these dinosaurs might have hunted in groups. The “Wankel” site in eastern Montana yielded several T. rex individuals of different ages preserved together, suggesting possible social behavior. If T. rex did hunt in family groups or packs, it would significantly enhance their ability to take down large prey like Triceratops, which weighed up to 12 tons. Pack hunting would also align with T. rex’s classification as a tyrannosaurid, a family that includes other species that show evidence of group behavior. However, the fossil evidence remains inconclusive, as multiple individuals could have been drawn to the same food source or died in unrelated events and been preserved together. Trackway evidence that might conclusively demonstrate pack behavior has yet to be discovered for T. rex, leaving this aspect of its predatory behavior still open to debate.

Sensory Capabilities: Built for Hunting

Montana T. rex skulls have provided invaluable insights into the dinosaur’s sensory abilities, which strongly suggest adaptation for hunting. CT scans of T. rex braincases reveal an enlarged olfactory bulb, indicating an exceptional sense of smell that could track prey from considerable distances. This feature would be useful for both hunting and scavenging. More tellingly, T. rex had forward-facing eyes with approximately 55-degree binocular vision, comparable to modern hawks, providing the depth perception crucial for judging distances when attacking moving prey. The dinosaur also possessed unusually large optic lobes, suggesting excellent vision even in low light conditions. Perhaps most surprisingly, recent studies of inner ear anatomy from Montana specimens indicate T. rex had exceptional hearing in the low-frequency range, potentially allowing it to detect the footfalls and movements of large prey animals from significant distances. This suite of highly developed senses points to an animal adapted for active hunting rather than simple scavenging.

The Tiny Arms: Predatory Limitation or Specialized Tool?

T. rex’s infamously small forelimbs have often been cited as evidence against predatory behavior, as they appear too short to grasp struggling prey. However, detailed analysis of arm fossils from Montana specimens has revealed surprising strength. Despite their short length, T. rex’s arms could likely curl over 400 pounds each, suggesting they served some functional purpose. Recent theories propose these arms may have been used to hold prey close to the body after it had been subdued by the powerful jaws, to help the dinosaur rise from a resting position, or even as specialized adaptations for specific feeding behaviors. Interestingly, the reduction in arm size seems to have evolved in concert with increasing jaw power across tyrannosaur evolution, suggesting a tradeoff where predatory functions shifted from the arms to the head. This evolutionary trend indicates that while the arms were reduced, they were not vestigial and likely complemented T. rex’s predatory lifestyle rather than hindering it.

Stomach Contents and Coprolites: Direct Dietary Evidence

Perhaps the most direct evidence of T. rex’s feeding habits comes from rare preserved stomach contents and fossilized feces (coprolites) found in Montana. Several coprolites attributed to T. rex contain large quantities of crushed bone fragments, indicating the dinosaur consumed and processed entire prey animals rather than just selecting soft tissues, as many scavengers do. One particularly revealing specimen discovered near Jordan, Montana, contained partially digested hadrosaur bones showing both bite marks and digestive etching. The composition of these remains suggests T. rex had a digestive system capable of processing large quantities of bone, similar to modern hyenas but on a much larger scale. While stomach contents cannot definitively determine whether the consumed animals were hunted or scavenged, the quantity and variety of bone fragments indicate T. rex was consuming substantial amounts of other dinosaurs, requiring either very successful hunting or extraordinary luck in finding fresh carcasses.

The Montana Ecosystem: Predator-Prey Relationships

Reconstructing the Hell Creek ecosystem from Montana fossils provides valuable context for understanding T. rex’s ecological role. This late Cretaceous environment was dominated by large herbivorous dinosaurs, including multiple species of hadrosaurs, ceratopsians, and ankylosaurs, providing ample potential prey for large predators. Population estimates suggest herbivores vastly outnumbered predators, with perhaps one T. rex for every hundred potential prey animals, a ratio similar to modern predator-prey ecosystems. Interestingly, Hell Creek shows relatively low diversity of large predatory dinosaurs compared to earlier formations, with T. rex being the dominant apex predator in its environment. This monopoly on the large predator niche suggests T. rex was filling the ecological role of active predator rather than just scavenger, as pure scavenging would likely not have provided enough selective pressure to drive competitors to extinction. The abundance of potential prey animals with adaptations suggesting predator avoidance (like the defensive horns of Triceratops) further indicates an ecosystem shaped by active predation rather than just scavenging.

Isotope Analysis: Chemical Clues to Feeding Habits

Advanced chemical analyses of T. rex teeth and bones from Montana specimens have provided new insights into the dinosaur’s diet and feeding habits. Stable isotope analyses, which examine the ratios of elements like carbon and nitrogen, can reveal an animal’s position in the food web and dietary preferences. Recent studies have shown that T. rex isotope signatures are consistent with those of a top predator rather than a pure scavenger. Particularly telling are nitrogen isotope ratios, which become concentrated at higher levels of the food chain. T. rex shows enrichment patterns similar to other known predators rather than specialized scavengers. Additionally, trace element analysis of T. rex teeth has revealed seasonal variations in diet, suggesting the dinosaur adapted its feeding strategies throughout the year rather than exclusively relying on one food source. These chemical signatures provide compelling evidence that T. rex occupied the ecological niche of an apex predator that primarily consumed freshly killed prey, though likely supplemented with scavenging when opportunities arose.

The Evolutionary Perspective: Ancestry and Adaptations

Examining T. rex within its evolutionary context provides further insights into its likely feeding behaviors. T. rex belonged to the tyrannosaurid family, which shows a clear evolutionary trajectory toward increasing size, more powerful jaws, and reduced forelimbs over millions of years. Earlier tyrannosaurids like Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus show adaptations consistent with active predation, suggesting T. rex evolved from a lineage of predators rather than scavengers. Comparative studies with other large theropods from different continents reveal convergent evolution toward features associated with active hunting, indicating strong selective pressure for predatory adaptations. Perhaps most tellingly, juvenile T. rex specimens from Montana show proportionally longer legs, more blade-like teeth, and more gracile builds than adults, suggesting young T. rexes were active pursuit predators before growing into their more robust adult form. This ontogenetic shift may represent a change in hunting strategies rather than a complete shift from predator to scavenger, with adults potentially specializing in hunting larger, more dangerous prey that required extraordinary bite force.

The Modern Synthesis: Predator and Scavenger

Current scientific consensus based on Montana fossils and other evidence points to T. rex as both predator and opportunistic scavenger, similar to modern large carnivores. Today’s lions, hyenas, and wolves regularly hunt prey but will readily scavenge when opportunities arise, and the evidence suggests T. rex likely behaved similarly. This balanced view is supported by the totality of fossil evidence, which includes features advantageous for both hunting (binocular vision, powerful legs) and scavenging (exceptional sense of smell, bone-crushing bite). The dinosaur’s enormous size and caloric requirements would have necessitated a flexible feeding strategy that took advantage of all available food sources. Most paleontologists now believe T. rex was primarily a predator that would have readily scavenged when convenient—a behavior pattern that maximizes energy intake while minimizing risk. This nuanced understanding of T. rex’s feeding behavior provides a more complete and realistic picture of how this iconic dinosaur actually functioned within its ancient ecosystem.

Conclusion

The ongoing discovery and analysis of T. rex fossils from Montana continue to refine our understanding of this magnificent prehistoric predator. While the perfect “smoking gun” evidence that would definitively settle the predator-scavenger debate may never be found, the accumulating evidence strongly suggests T. rex was indeed an apex predator that also scavenged opportunistically. This conclusion aligns with what we observe in modern ecosystems, where large carnivores exhibit flexibility in their feeding strategies. The Hell Creek Formation in Montana, with its exceptional preservation and abundant T. rex remains, remains at the forefront of research into this question, promising further insights as new specimens are unearthed and more sophisticated analytical techniques are developed. As our understanding evolves, one thing remains certain: T. rex was a remarkably successful and specialized carnivore whose adaptations allowed it to dominate its ecosystem until the very end of the Age of Dinosaurs.