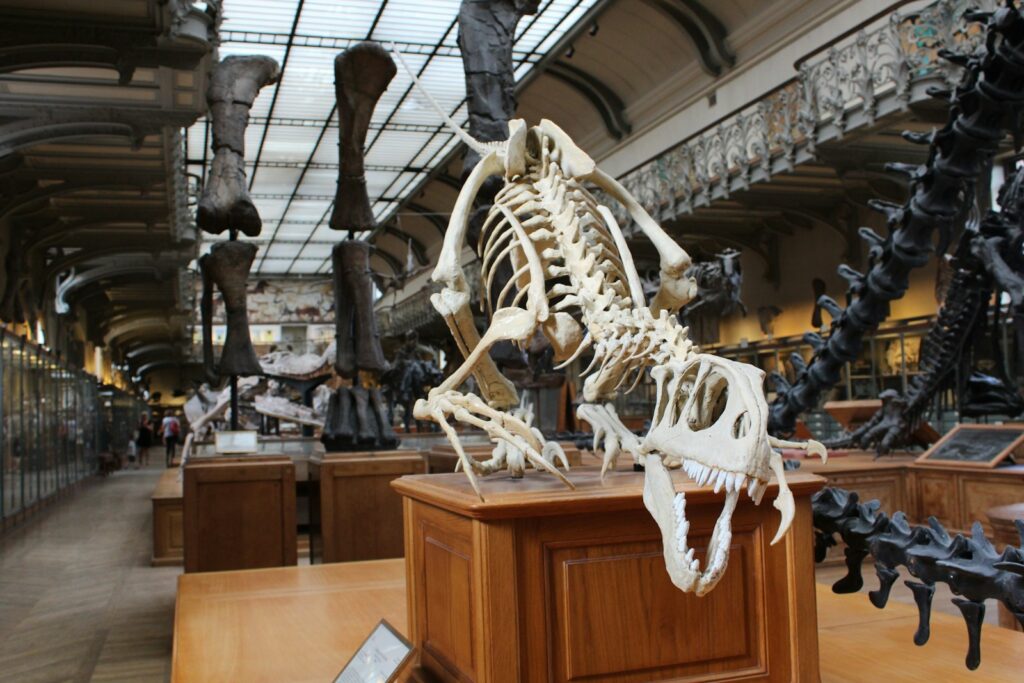

In museums worldwide, impressive dinosaur skeletons and ancient human remains captivate visitors with their imposing presence and historical significance. These star specimens represent extraordinary discoveries that have shaped our understanding of evolutionary history. Yet, for every fossil that makes headlines and finds its way into prestigious display cases, thousands more remain unseen by the public eye. These “forgotten fossils” – the countless specimens that don’t capture media attention – form the backbone of paleontological research. What happens to these less spectacular but equally valuable discoveries? Where do they go, and what role do they play in science? This article explores the untold journey of ordinary fossils, from discovery to storage, and their crucial importance to scientific understanding.

The Vast Fossil Record: A Numbers Game

The sheer volume of fossils discovered annually would astonish most people. Each year, professional paleontologists and amateur fossil hunters unearth tens of thousands of specimens worldwide. Natural history museums like the Smithsonian Institution house millions of fossils in their collections, with only about 1% ever displayed for public viewing. These numbers reveal an important truth: paleontology exists primarily in storage facilities, not exhibition halls. Most specimens never make headlines because they represent already-known species or consist of fragmentary remains rather than complete skeletons. Yet collectively, these ordinary fossils provide the statistical basis for understanding ancient life, offering crucial data points that help scientists trace evolutionary patterns, confirm species distributions, and verify existing theories.

The Journey from Field to Facility

When paleontologists discover fossils in the field, a methodical process begins that determines their ultimate fate. Field researchers carefully document each specimen’s exact location, orientation, and geological context before extraction. These specimens then undergo preliminary cleaning and stabilization, often using specialized adhesives to prevent fragmentation during transport. Upon arrival at research facilities, technicians remove the surrounding matrix material and conduct more thorough preparation. This preparation process can take months or even years for significant specimens. However, many less remarkable fossils might receive only minimal preparation before being cataloged and stored. The level of attention a fossil receives often depends on its perceived scientific importance, preservation quality, and the resources available to the institution that houses it.

Behind Museum Doors: The Repository System

Most scientific institutions maintain vast fossil repositories that serve as libraries of Earth’s past life. These temperature-controlled storage facilities house specimens in organized drawer systems, organized by taxonomic classification, geological age, or geographic origin. The American Museum of Natural History, for example, stores millions of fossils in specialized cabinets that protect them from environmental damage and deterioration. Curators maintain meticulous catalog systems that track each specimen’s information, including where and when it was found, who collected it, and its taxonomic identification. These repositories function as scientific archives, preserving evidence of past life that researchers can access for future studies. Modern institutions increasingly digitize their collections, creating virtual databases that allow scientists worldwide to search for specific specimens without physical visits.

The Scientific Value of Ordinary Specimens

While complete skeletons of rare species make headlines, the scientific value of common, fragmentary fossils is immeasurable. These ordinary specimens provide the statistical foundation for understanding species variation, population structures, and evolutionary trends. A single spectacular T. rex skeleton might capture public imagination, but dozens of fragmentary T. rex fossils allow scientists to determine growth patterns, population distribution, and anatomical variations within the species. Similarly, thousands of cataloged trilobite specimens enable researchers to trace evolutionary changes across millions of years with statistical confidence. The scientific method relies on replicated observations and patterns, making these abundant “common” fossils essential for drawing reliable conclusions about ancient life. Without these forgotten fossils, paleontologists would be limited to making speculative assertions based on isolated spectacular specimens.

The Problem of Storage Capacity

As fossil collections continue to grow, museums and research institutions face increasing challenges with storage capacity. Many facilities have reached their maximum capacity, forcing difficult decisions about what to keep and what to deaccession. The Field Museum in Chicago, for instance, houses over 30 million specimens across all collections, requiring nearly 300,000 square feet of storage space that costs millions to maintain annually. This storage crisis has led some institutions to consider controversial solutions, including transferring specimens to other facilities, returning them to their countries of origin, or, in rare cases, deaccessioning less scientifically valuable materials. Space limitations often mean newly discovered common specimens might receive less priority than unusual or well-preserved examples. Some institutions have implemented moratoriums on accepting certain common fossil types unless they demonstrate exceptional scientific value or preservation quality.

The Role of Type Specimens and Reference Collections

Among stored fossils, certain specimens hold special status that guarantees their permanent preservation. “Type specimens” represent the official reference examples used to define species in scientific literature. When paleontologists name a new species, they designate one specific fossil as the holotype—the definitive example of that species against which all other potential members are compared. The Tyrannosaurus rex holotype resides at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, while “Sue,” the famous T. rex at the Field Museum, is not a type specimen despite its completeness. Beyond holotypes, reference collections consist of well-documented specimens that represent the standard examples of known species. These specimens receive priority conservation attention and storage considerations because they serve as the fundamental reference points for taxonomic identification. Most major museums maintain extensive type and reference collections that form the cornerstone of their research value.

Forgotten Fossils and Citizen Science

Amateur fossil collectors and citizen scientists play a crucial role in recovering fossils that might otherwise remain undiscovered. Many significant specimens in museum collections were initially found by hobbyists who donated their discoveries to scientific institutions. The famous Archaeopteryx specimen that helped confirm the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds was discovered by a quarry worker in Germany rather than a professional paleontologist. Today, numerous museums operate volunteer programs that allow enthusiasts to participate in fossil preparation and cataloging work. The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County maintains a volunteer program where participants help process the backlog of uncatalogued specimens, making them accessible to researchers. These citizen science initiatives not only expand institutional capacity but also foster public appreciation for the scientific value of ordinary fossils that rarely make headlines.

Digital Resurrection: Bringing Forgotten Fossils to Light

Modern technology has revolutionized the way researchers access and study stored fossil collections. Digitization initiatives at major institutions now create 3D scans of specimens, making them virtually accessible to scientists worldwide without requiring physical access to storage facilities. The Digital Atlas of Ancient Life project has created online databases featuring thousands of fossils that would otherwise remain unseen in drawers. These digital repositories allow researchers to examine specimens remotely, compare collections from different institutions, and conduct large-scale statistical analyses that would be impossible with physical access alone. Technologies like CT scanning reveal internal structures of fossils without damaging them, while photogrammetry creates detailed 3D models from multiple photographs. These technological advances essentially “resurrect” forgotten fossils from storage obscurity, giving them new scientific life without requiring public display space.

When Old Collections Yield New Discoveries

Some of paleontology’s most significant breakthroughs have come not from new field expeditions but from reexamining forgotten specimens already stored in collections. In 2017, researchers discovered a new species of titanosaur dinosaur by studying fossils that had been sitting in the Natural History Museum of London’s collections since the 1930s. Similarly, the dinosaur Spinosaurus was redescribed based on specimens collected in the early 1900s when researchers recognized their significance decades later. These examples highlight how scientific advancements and new analytical techniques can extract new information from long-stored specimens. Modern techniques like stable isotope analysis, ancient DNA extraction, and microscopic examination of growth patterns allow researchers to answer questions about ancient organisms that weren’t possible when the specimens were first collected. This reality means that even the most ordinary-seeming fossil might yield extraordinary insights when examined with future technologies or theoretical frameworks.

The Ethics of Fossil Collection and Storage

The accumulation of fossils in institutional collections raises important ethical questions about scientific responsibility and cultural patrimony. Many significant fossil collections were amassed during colonial eras when specimens were removed from their countries of origin without consideration for local scientific development or cultural significance. Today, paleontologists debate the ethics of where fossils should be housed and who should have authority over their study and display. Countries like Mongolia, China, and Argentina have enacted strict laws preventing the export of fossils found within their borders, viewing them as national scientific patrimony. Meanwhile, some institutions have begun repatriating historically collected specimens to their countries of origin. These ethical considerations influence decisions about which fossils institutions accept, how they document provenance, and who has access to study them. Responsible collection practices now emphasize collaboration with local scientists and respect for both legal regulations and the scientific capacity of fossil-rich nations.

The Educational Value of Secondary Specimens

While museums display their finest specimens, many “second-tier” fossils serve crucial educational purposes in classrooms and teaching collections. Universities maintain teaching collections where students can directly handle and study actual fossil specimens rather than replicas. The University of California Museum of Paleontology provides fossil specimens to geology and biology courses, allowing students to examine real examples of ancient life. Similarly, many museums maintain educational “touch tables” where visitors can handle less scientifically valuable specimens to experience fossils directly. Some institutions even develop traveling collections that bring fossils to schools and community centers, particularly in areas with limited museum access. These educational specimens might lack the completeness or rarity to warrant display or intensive research, but they play an invaluable role in training future scientists and fostering public appreciation for paleontology.

Fossil Localities: The Contextual Record

Beyond individual specimens, paleontologists preserve extensive records of fossil localities—the sites where specimens were discovered. These locality records document the geological context, associated fauna and flora, and environmental conditions that provide crucial scientific context for individual fossils. Major research institutions maintain vast databases of these localities, often including specimens, soil samples, photographs, and field notes. The University of California Museum of Paleontology has documented over 200,000 fossil localities worldwide, providing an invaluable resource for understanding ancient ecosystems. When researchers study a specific fossil, they often reference all specimens from the same locality to understand the broader ecological context. This locality information frequently proves more scientifically valuable than isolated spectacular specimens, as it enables reconstruction of entire ancient ecosystems rather than just individual species. Protecting this contextual information represents one of the strongest arguments against unregulated commercial fossil collecting, which often prioritizes spectacular specimens over systematic documentation.

The Future of Forgotten Fossils

As paleontology evolves, the fate of forgotten fossils continues to transform through technological and methodological innovations. Artificial intelligence applications now help catalog massive fossil collections, identifying patterns and relationships that might escape human observation. Cloud-based storage systems allow institutions to share data about their collections, creating virtual global repositories that transcend physical storage limitations. Some facilities have begun using robotics systems for specimen retrieval, making stored collections more accessible to researchers. Looking forward, emerging technologies like ancient protein analysis and advanced stable isotope techniques promise to extract new information from long-stored specimens. Perhaps most importantly, changing perspectives on what constitutes scientific value mean that previously overlooked specimens—like microfossils, trace fossils, and fragmentary remains—increasingly receive research attention. The forgotten fossils of today may well become the research foundations of tomorrow as scientific questions and methodologies continue to evolve.

Conclusion: The Silent Majority of the Fossil Record

The spectacular fossils that capture public imagination represent just the tip of an immense iceberg of paleontological knowledge. The true foundation of our understanding of ancient life rests upon the countless ordinary specimens that fill museum drawers and storage facilities worldwide. These forgotten fossils—the fragments, the duplicates, the common species—collectively tell us more about Earth’s history than any single spectacular skeleton ever could. They provide the statistical power, the geographic distribution, and the evolutionary context essential for scientific interpretation. As technology advances and research questions evolve, these stored specimens continue to yield new insights, often decades or centuries after their discovery. The next time you admire a magnificent dinosaur skeleton in a museum hall, remember that its scientific significance depends on the thousands of less impressive specimens hidden from view, patiently waiting in drawers and cabinets for their chance to contribute to our understanding of life’s remarkable history.