The prehistoric world showcased some of the most spectacular creatures ever to walk the Earth, from the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex to the massive herbivores that shared its ecosystem. While carnivores like T. rex often dominate our imagination of prehistoric power dynamics, several herbivorous dinosaurs possessed formidable defenses and physical attributes that potentially made them capable of standing their ground against predators. This article explores the most powerful herbivores from the age of dinosaurs and contemplates whether any could successfully defend themselves against the infamous “tyrant lizard king.”

Defining Power in Herbivorous Dinosaurs

When discussing power among herbivores, several metrics must be considered beyond mere size. Defensive capabilities, physical strength, social behaviors, and anatomical weaponry all contribute to an animal’s ability to protect itself. The most powerful herbivores typically combined massive body size with specialized defensive adaptations like horns, clubs, or spikes. Some employed herd defense tactics, while others relied on sheer bulk and strength. These various adaptations served specific purposes in deterring predators, with some potentially effective enough to give even the mightiest carnivores pause. Understanding these power dynamics requires looking beyond traditional assumptions about predator-prey relationships and examining the sophisticated evolutionary arms race between herbivores and the predators that hunted them.

Triceratops: The Three-Horned Defender

Triceratops stands as one of the most iconic defensive herbivores, equipped with three formidable horns and a massive frill that protected its neck. Growing up to 30 feet long and weighing 5-9 tons, this ceratopsian possessed a bony shield that could potentially withstand bites from predators. Its two brow horns, sometimes exceeding 3 feet in length, served as powerful weapons capable of goring attackers. Fossil evidence suggests that Triceratops engaged in combat not only with predators but also with members of its own species, indicating these weapons weren’t merely for show. The animal’s low center of gravity and wide stance provided stability during confrontations, allowing it to potentially charge like a modern rhinoceros. When facing a T. rex, a healthy adult Triceratops could pose a significant threat, potentially inflicting fatal wounds with its horns while using its frill to protect vulnerable areas.

Ankylosaurus: The Armored Tank

Ankylosaurus represents nature’s answer to a battle tank, covered from head to tail in thick osteoderms that formed a nearly impenetrable armor. This 20-26 foot long herbivore reached weights of 4-8 tons and possessed one of the most effective defensive adaptations in dinosaur history—a massive tail club that could shatter bones on impact. Studies suggest this club could generate forces strong enough to break the leg bones of even large predators. The animal’s low-slung profile offered few vulnerable attack points, while its broad body made it difficult to topple. Ankylosaurus lived alongside T. rex in Late Cretaceous North America, evolving its extreme defenses specifically to counter such apex predators. A direct hit from an Ankylosaurus tail club could potentially disable or even kill a T. rex, making it one of the few herbivores that might not only defend itself but actively deter predation through offensive capability.

Stegosaurus: The Spiked Defender

Stegosaurus, though not a contemporary of T. rex, warrants discussion as one of the most distinctively armed herbivores in dinosaur history. This Jurassic giant, stretching up to 30 feet long and weighing 5-7 tons, featured massive upright plates along its back and a thagomizer—a cluster of four to eight spikes—on its tail. Research suggests these tail spikes could deliver devastating blows to predators, with evidence of Allosaurus bones bearing puncture wounds consistent with Stegosaurus defense. The animal’s relatively small head contained a brain roughly the size of a walnut, leading to speculation about a second “brain” near its hips to control its rear defenses, though scientists now believe this was actually an enlarged nerve cluster. Despite its formidable weaponry, Stegosaurus moved relatively slowly and lacked the quick reflexes of later armored dinosaurs. Had it somehow encountered a T. rex (which evolved approximately 85 million years later), its defensive capabilities would have been tested against a predator far more powerful than those it evolved to counter.

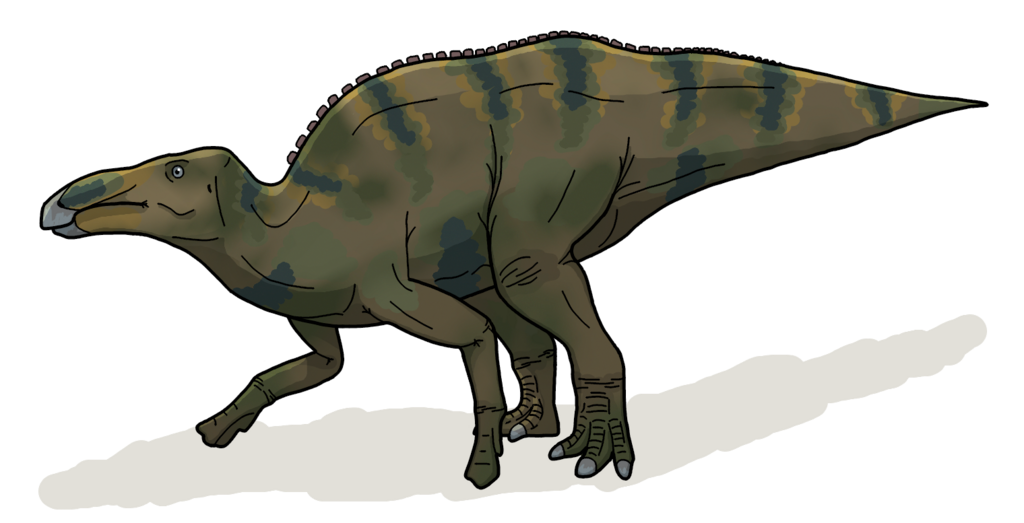

Shantungosaurus: The Colossal Hadrosaur

Shantungosaurus stands as possibly the largest known ornithischian dinosaur, dwarfing many of its contemporaries with its massive proportions. This duck-billed dinosaur reached lengths of up to 50 feet and potentially weighed 15-16 tons—comparable to some sauropods and significantly outweighing even the largest T. rex specimens. Unlike many powerful herbivores, Shantungosaurus lacked obvious defensive weapons, instead relying primarily on its sheer size and possibly herd behavior for protection. Its powerful hind legs could have delivered devastating kicks, while its muscular tail could generate substantial force when swung. Modern analogies with large herbivores like hippopotamuses suggest that size alone can be an effective deterrent against predation. Though physically imposing, Shantungosaurus evolved in Asia and would not have encountered T. rex directly, instead contending with large tyrannosaurs like Tarbosaurus. Its massive bulk may have made adults too risky for even large predators to attack, though juveniles would have remained vulnerable.

Argentinosaurus: The Ultimate Heavyweight

When discussing pure size and power, few dinosaurs compare to Argentinosaurus, one of the largest land animals ever to exist. This titanosaur sauropod reached estimated lengths of 100-115 feet and potentially weighed 70-80 tons—dimensions that put it well beyond the predatory capabilities of even the largest theropods. Argentinosaurus didn’t need specialized defensive adaptations; its titanic proportions served as its primary defense. An adult could likely have crushed any predator with a single stomp or tail swipe, generating forces far beyond what even the most robust carnivore could withstand. The sheer scale differential between even the largest T. rex (estimated at 8-9 tons) and Argentinosaurus made predation on healthy adults virtually impossible. However, Argentinosaurus lived in South America during the Late Cretaceous and would never have encountered T. rex, instead facing predators like Giganotosaurus and Mapusaurus. These large carnivores likely focused on juvenile sauropods or attacked adults through pack hunting strategies, targeting vulnerable individuals.

Therizinosaurus: The Scythe-Clawed Herbivore

Therizinosaurus represents one of the most unusual cases among powerful herbivores, possessing massive claws that stretched up to three feet in length—the longest of any known animal. Despite being a theropod (the same group that includes T. rex), this bizarre dinosaur evolved to eat plants while retaining and enlarging its ancestral claws. Standing potentially 15-20 feet tall and weighing 3-5 tons, its slender build belied formidable defensive capabilities. The function of its enormous claws has been debated, with theories including defense, pulling down branches, or digging for roots, but their potential as weapons cannot be overlooked. When threatened, Therizinosaurus could likely have inflicted devastating slashing wounds on predators. Interestingly, this dinosaur lived alongside Tarbosaurus (an Asian relative of T. rex) in Late Cretaceous Mongolia, suggesting its unusual adaptations evolved specifically to counter large tyrannosaur predation. A confrontation between Therizinosaurus and a large tyrannosaur would have presented a unique match-up between two theropods with dramatically different specializations.

Parasaurolophus: The Vocal Defender

Parasaurolophus represents an interesting case of a herbivore that may have used non-physical defense mechanisms as its primary protection strategy. This hadrosaur, measuring up to 33 feet long and weighing 2-3 tons, is best known for its elaborate hollow crest extending from the back of its skull. Scientific studies suggest this crest functioned as a resonating chamber, potentially allowing the animal to produce loud, low-frequency sounds that could travel long distances. Such vocalizations may have served as alarm calls, coordinating herd movements when predators were detected. Unlike more heavily armed herbivores, Parasaurolophus likely relied on early warning systems and rapid flight to escape predators, potentially using its powerful hind legs to run at speeds of 25-30 mph. While not equipped to directly confront a T. rex, its sophisticated communication system might have provided sufficient warning time to flee before an attack materialized. The fossil record shows that hadrosaurs were among T. rex’s common prey items, suggesting their defensive strategies were not always successful against the apex predator.

Pachyrhinosaurus: The Bone-Headed Charger

Pachyrhinosaurus offers an alternative defensive strategy within the ceratopsian family, substituting the typical horns for a massive, roughened bone pad called a nasal boss. This 18-23 foot long herbivore weighed approximately 4 tons and lived in northern North America during the Late Cretaceous. Rather than goring predators like its relative Triceratops, Pachyrhinosaurus likely used its thickened nasal area for powerful ramming attacks, potentially delivering concussive blows to attackers. Fossil evidence suggests these dinosaurs engaged in head-butting contests with each other, indicating the impressive strength of their cranial structures. The animal’s frill, while less dramatic than some ceratopsians, still provided crucial neck protection against predator bites. Pachyrhinosaurus shared its habitat with tyrannosaurs including Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus, though not T. rex specifically. Its combat strategy of delivering high-impact collisions might have been effective against predators, particularly when combined with herd defense tactics that multiple specimens could employ simultaneously.

The Prehistoric Power Balance

The relationship between predator and prey in the dinosaur world represented an evolutionary arms race spanning millions of years. As carnivores developed more sophisticated hunting techniques and more powerful jaws, herbivores responded with increasingly effective defensive adaptations. This dynamic equilibrium meant neither group gained a permanent advantage, instead creating ecosystems where both could persist through specialized adaptations. Fossil evidence occasionally provides glimpses of direct confrontations, such as a Triceratops with healed T. rex bite marks or tyrannosaur bones showing injury patterns consistent with defensive wounds. Environmental factors also played crucial roles in these interactions, with terrain, visibility, and even time of day potentially determining the outcome of predator-prey encounters. The fossil record suggests that predation success rates were likely similar to those in modern ecosystems—with most attempted predations resulting in failure, especially against healthy adult herbivores. This balance of power ensured that both predator and prey populations remained stable over evolutionary timeframes, with neither gaining a decisive advantage.

Modern Analogies: Learning from Today’s Megafauna

Studying modern ecosystems provides valuable insights into how prehistoric herbivores might have defended themselves against predators like T. rex. African elephants, weighing up to 13,000 pounds, can successfully deter pride attacks from lions weighing just 400-500 pounds—a size differential comparable to some dinosaur encounters. Observations show that adult rhinoceros, hippopotamus, and cape buffalo can all effectively defend themselves against predators, often becoming dangerous adversaries when threatened. These modern examples demonstrate that herbivores with sufficient size, weaponry, or aggressive temperament can not only survive but dominate confrontations with predators. Particularly telling is the case of mother elephants, which become extraordinarily dangerous when protecting calves, suggesting parental defense may have been a significant factor in dinosaur confrontations as well. The social dynamics of modern herding animals also provide models for understanding how dinosaur herds might have coordinated their defenses, potentially forming defensive circles around vulnerable juveniles when threatened by predators like T. rex.

Size vs. Weaponry: What Mattered More?

The question of whether size or specialized weaponry provided better protection against predators remains complex, with evidence suggesting different advantages in different contexts. Massive sauropods like Argentinosaurus rarely needed specialized defenses due to their sheer bulk placing them beyond the predatory capabilities of even the largest carnivores once they reached adulthood. Medium-sized herbivores like ceratopsians and ankylosaurs, meanwhile, evolved elaborate defensive adaptations precisely because they existed within the size range that made them potential prey. The fossil record indicates that the most successful herbivores combined moderate to large size with specialized defenses—creating a sweet spot of defensive capability. Ankylosaurs, for example, combined significant bulk with armor and active weaponry, while Triceratops paired its three-ton mass with formidable horns. Environmental factors also influenced which attributes proved most valuable; open plains might favor speed and herding behavior, while densely forested areas might advantage armored, solitary defenders. This suggests that the most effective protection against predators like T. rex likely came from complementary combinations of size, weaponry, and behavior rather than any single attribute.

The Verdict: Could Any Herbivore Defeat a T. Rex?

Based on paleontological evidence and biomechanical studies, several herbivorous dinosaurs possessed the physical capabilities to potentially survive an encounter with a Tyrannosaurus rex under the right circumstances. Adult specimens of Triceratops and Ankylosaurus represent the most formidable candidates, combining sufficient size with specialized weapons specifically evolved to counter large predators in their ecosystems. Triceratops’ lethal horns could inflict devastating injuries if they connected with vulnerable areas, while an Ankylosaurus tail club could potentially break bones with a well-placed strike. Extremely large herbivores like Shantungosaurus or sauropods might have been effectively immune to predation as adults simply due to their massive size, though they lacked the active defensive weapons of their medium-sized counterparts. The fossil record indicates that T. rex was a successful predator but not an invincible one—it evolved in ecosystems containing herbivores with sophisticated defenses, suggesting a complex relationship where neither predator nor prey held absolute advantage. In the prehistoric power balance, healthy adult specimens of several herbivore species could likely defend themselves successfully against even the most fearsome predator of their time.

The confrontation between prehistoric herbivores and their predators reminds us that nature rarely creates one-sided relationships. For every evolutionary advancement in predatory ability, prey species developed countermeasures that allowed their continued survival. While T. rex remains an icon of prehistoric power, the herbivores that shared its world were far from defenseless victims—they were sophisticated, well-adapted survivors whose defensive capabilities ensured the continuation of their lineages across millions of years. The most powerful among them didn’t need to defeat T. rex in combat; they simply needed to make predation too costly and risky to be worthwhile. In this evolutionary chess match, massive size, specialized weaponry, and effective defensive behaviors created herbivores fully capable of standing their ground against even the most iconic predator in Earth’s history.