When we imagine dinosaurs, we often picture solitary predators like Tyrannosaurus rex stalking prey or lone plant-eaters grazing on prehistoric vegetation. However, paleontological evidence increasingly suggests that many dinosaur species were highly social creatures that lived and traveled in groups. Fossilized trackways, bone beds containing multiple individuals, nesting sites, and anatomical features all point to complex social behaviors among certain dinosaur species. These social dynamics likely provided advantages in protection from predators, successful reproduction, juvenile care, and efficient foraging. The discovery of herding behaviors has fundamentally changed our understanding of dinosaur life and offers fascinating insights into how these magnificent creatures thrived for over 165 million years.

Evidence for Dinosaur Sociality

Paleontologists have uncovered several types of evidence that point to social behavior in dinosaurs. Perhaps the most compelling are mass bone beds, where dozens or even hundreds of individuals of the same species are found together, suggesting they died as a group during a catastrophic event. Trackway sites showing multiple sets of footprints moving in the same direction provide direct evidence of coordinated movement. Nesting colonies, where numerous nests are found in close proximity, indicate communal breeding behavior. Additionally, some dinosaurs possessed physical features like elaborate crests, frills, or display structures that likely served social signaling functions. These various lines of evidence, when taken together, paint a picture of dinosaurs as often highly social creatures rather than the solitary animals they were once believed to be.

Maiasaura: The “Good Mother Lizard”

Maiasaura, whose name literally means “good mother lizard,” represents one of the most compelling examples of social dinosaurs. These hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) lived in the Late Cretaceous period in what is now Montana. Paleontologist Jack Horner discovered remarkable evidence of their social nature in the form of massive nesting grounds containing thousands of nests arranged in a grid-like pattern, with nests spaced about 23 feet apart. Within these nests were found not only eggs but also the remains of hatchlings at different stages of development, suggesting extended parental care. The discovery of worn teeth in these juveniles indicates parents brought food to the nestlings until they were strong enough to join the herd. These findings revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur behavior, showing that at least some species engaged in complex social interactions and parental care reminiscent of modern birds.

Edmontosaurus: Herds of the Late Cretaceous

Edmontosaurus, another duck-billed dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous, left behind substantial evidence of herding behavior. Multiple bone beds containing hundreds of Edmontosaurus individuals have been discovered across North America, particularly in the western United States and Canada. One especially notable site in Alberta contains the remains of over 300 individuals that appear to have died together during a river crossing, possibly due to flooding. The composition of these herds reveals a fascinating social structure, with individuals of various ages present together. This age diversity suggests these weren’t merely temporary aggregations but stable, multi-generational social groups that may have traveled together year-round. Their large body size, reaching up to 40 feet in length, combined with safety in numbers, likely helped protect them from predators like Tyrannosaurus rex, which inhabited the same environments.

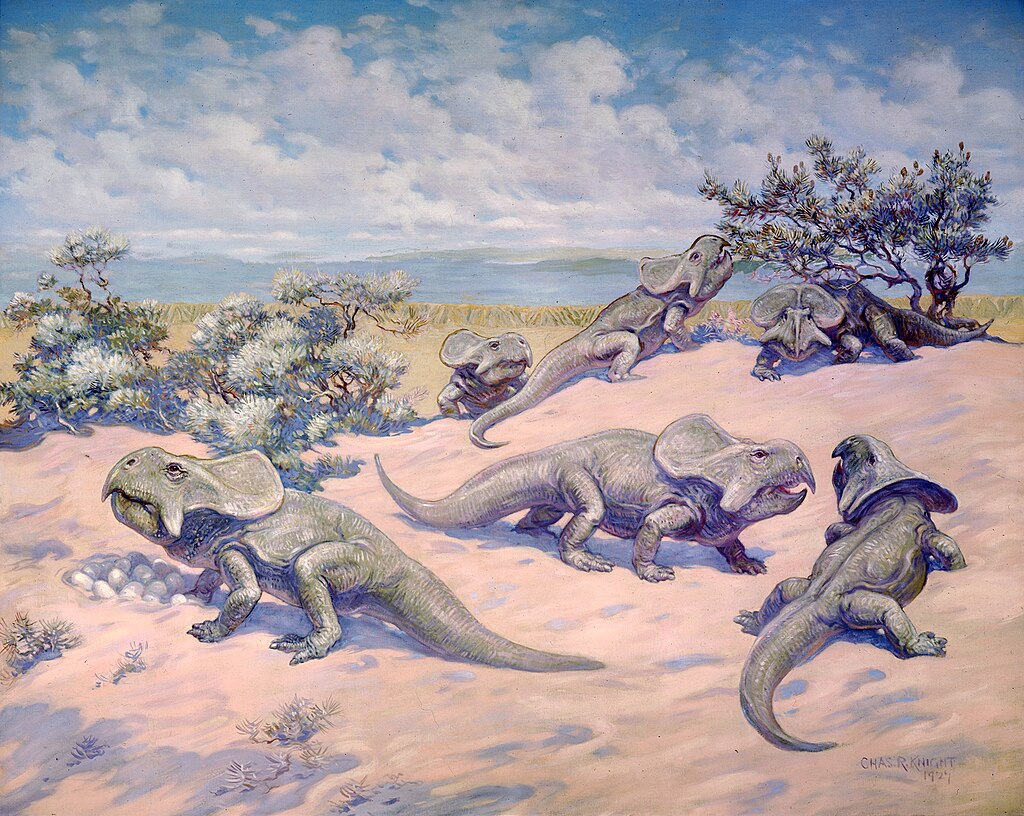

Protoceratops: Family Groups in the Gobi

Protoceratops, a sheep-sized relative of Triceratops that lived in Mongolia during the Late Cretaceous, has provided remarkable evidence of family-based social structures. Several specimens have been found clustered together in the Gobi Desert, including a famous fossil showing an adult surrounded by 15 juveniles of different sizes, potentially representing a family group. Even more compelling is the discovery of Protoceratops nesting colonies with multiple nests in close proximity, suggesting communal breeding arrangements. Some nests contain up to 30 eggs arranged in circular patterns, demonstrating sophisticated nesting behaviors. Interestingly, studies of Protoceratops frills suggest they may have served as social display structures rather than purely defensive adaptations, potentially used for species recognition and establishing dominance hierarchies within the social group.

Triceratops: Not Just Lone Warriors

Triceratops, one of the most iconic dinosaurs with its three horns and distinctive frill, has traditionally been portrayed as a solitary animal. However, more recent evidence has begun to challenge this view, suggesting these ceratopsians may have exhibited some degree of social behavior. Several Triceratops bone beds have been discovered containing multiple individuals, though not in the massive numbers seen with some other dinosaur species. Studies of Triceratops horns and frills show tremendous variety between individuals, which may have served as recognition features within social groups. Additionally, growth studies of Triceratops specimens indicate they may have formed age-segregated groups, with juveniles potentially staying together for protection until reaching adulthood. While they may not have formed the massive herds seen in hadrosaurs, the evidence suggests Triceratops likely engaged in more social interaction than previously thought.

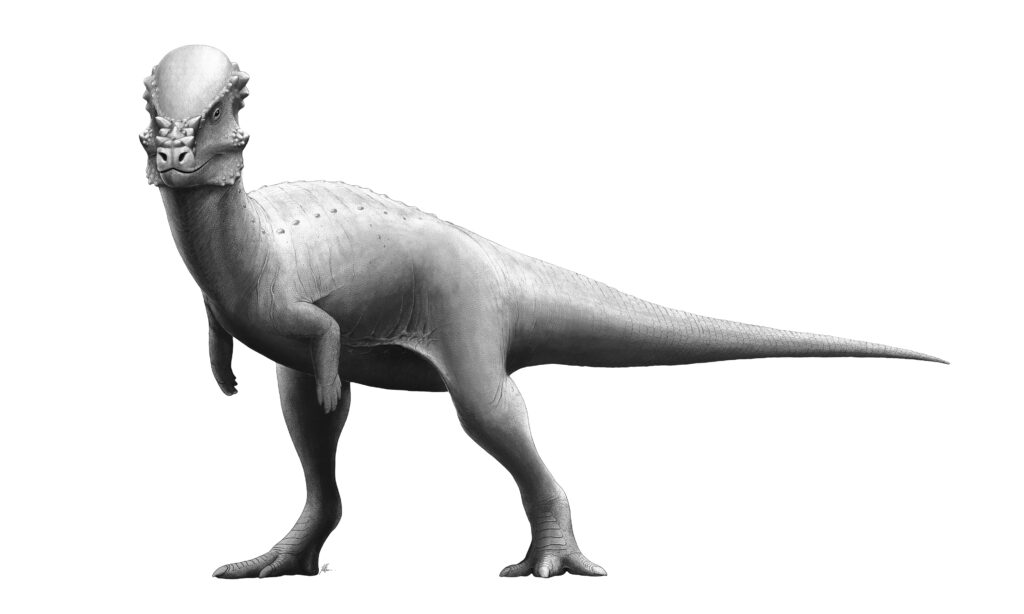

Pachycephalosaurus: Head-Butting Herd Members

Pachycephalosaurus, known for its distinctive dome-shaped skull roof up to 10 inches thick, presents an interesting case for social behavior. The thick skull has long been interpreted as an adaptation for head-butting contests between males, similar to behaviors seen in modern bighorn sheep or musk oxen. Such competitive behaviors typically evolve in the context of social groups where males compete for mating opportunities. While direct fossil evidence of Pachycephalosaurus herds is limited compared to some other dinosaurs, the specialized anatomy strongly suggests these animals engaged in social competitions. Some specimens show healed injuries consistent with head-butting impacts, further supporting this interpretation. Additionally, different pachycephalosaur species show variations in their dome shapes and ornamentations, suggesting these features may have served as species recognition signals within a social context, helping individuals identify potential mates or rivals from their own species.

Coelophysis: Early Evidence of Social Behavior

Coelophysis, a small, agile predator from the Late Triassic period, provides some of the earliest evidence for social behavior in dinosaurs. The Ghost Ranch quarry in New Mexico has yielded hundreds of Coelophysis skeletons packed together in a single bone bed, suggesting these animals may have lived or at least died together in a group. These slender, bipedal dinosaurs were relatively small, reaching about 10 feet in length and weighing around 50 pounds, making them potentially vulnerable to larger predators. Living in groups would have provided protection and possibly enhanced hunting success. The Ghost Ranch specimens include individuals of various ages, suggesting multi-generational groupings rather than age-segregated herds. Some paleontologists have suggested these animals may have hunted cooperatively, similar to some modern predators, though direct evidence for cooperative hunting behaviors remains speculative based on current fossil evidence.

Alamosaurus: Giant Sauropods in Groups

Alamosaurus, one of the last surviving sauropods in North America during the Late Cretaceous, has left evidence suggesting these massive dinosaurs moved in groups. Multiple individuals have been found in close proximity in several locations across the southwestern United States, particularly in New Mexico and Texas. As one of the largest land animals ever, reaching lengths of over 70 feet and weights potentially exceeding 70 tons, Alamosaurus would have gained substantial protection from predators by traveling in herds. Their immense size meant that adults had few predators, but juveniles would have been vulnerable to large theropods like Tyrannosaurus. Group living would have provided essential protection for younger individuals. Additionally, their high-browsing feeding strategy may have benefited from group foraging, as multiple individuals could more efficiently strip vegetation from large areas before moving on to new feeding grounds.

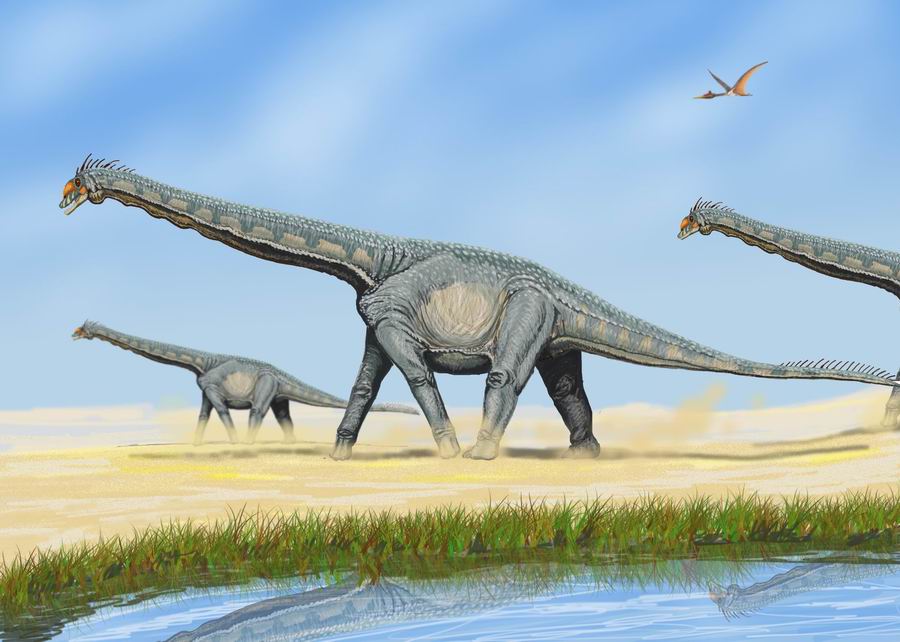

Diplodocus: Evidence of Sauropod Herding

Diplodocus and related sauropods from the Late Jurassic have provided substantial evidence for herding behavior among these long-necked giants. The Morrison Formation in the western United States has yielded several sites where multiple diplodocid sauropods have been found together, suggesting these animals traveled in groups. One particularly notable site in Wyoming contains the remains of multiple juvenile Diplodocus specimens, suggesting possible age-segregated herds where younger individuals stayed together. Trackway evidence has been especially revealing, with sites in Portugal, Spain, and the United States showing multiple sets of sauropod footprints moving in the same direction. These trackways indicate coordinated movement of multiple individuals, sometimes with smaller footprints (juveniles) positioned in the middle of the group, surrounded by larger footprints (adults) – a protective formation seen in many modern herding animals.

Psittacosaurus: Preserved Family Groups

Psittacosaurus, a small ceratopsian relative from the Early Cretaceous of Asia, has provided some of the most remarkable direct evidence of family groups among dinosaurs. One extraordinary fossil from China shows an adult Psittacosaurus surrounded by 34 juveniles, all preserved together in what appears to be a natural grouping rather than a result of post-mortem accumulation. The juveniles are all approximately the same size and developmental stage, suggesting they belonged to a single clutch being supervised by an adult. This exceptional preservation gives us a rare glimpse into direct parental care among dinosaurs. Other Psittacosaurus specimens have been found in small groups of mixed ages, further supporting their social nature. Additionally, studies of Psittacosaurus skin coloration have revealed countershading patterns that would have provided effective camouflage when moving together in wooded environments, another adaptation consistent with group living.

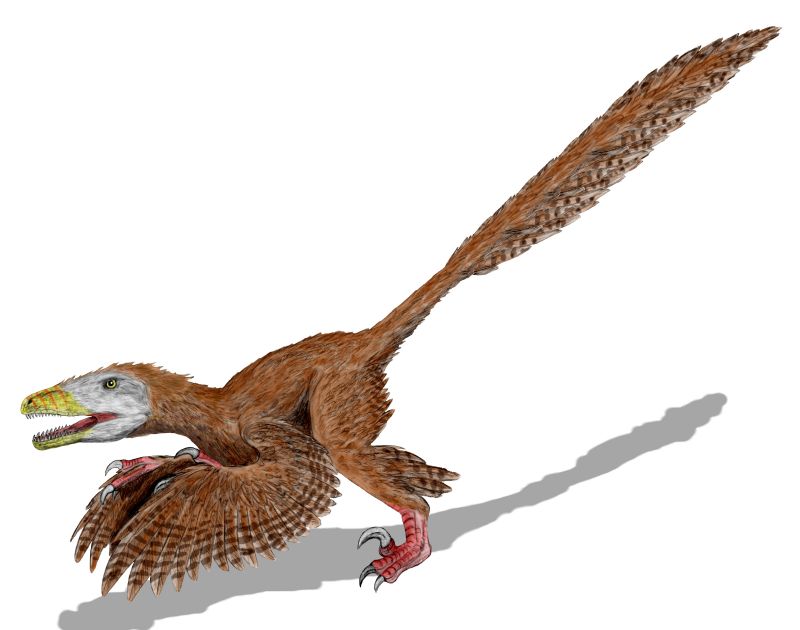

Deinonychus: Pack Hunters?

Deinonychus, the “terrible claw” dinosaur that inspired the Velociraptors in “Jurassic Park,” has long been hypothesized as a pack hunter based on several lines of evidence. Multiple Deinonychus specimens have been found associated with the remains of the larger herbivore Tenontosaurus, suggesting group hunting behavior. In some cases, shed teeth from multiple Deinonychus individuals surround a single Tenontosaurus carcass, indicating several predators fed on the same prey animal. The infamous sickle-shaped claws on their feet seem well-adapted for subduing large prey, which would have been difficult for a single Deinonychus to bring down alone. While some paleontologists have challenged the pack-hunting hypothesis in recent years, suggesting the associations might represent feeding aggregations rather than coordinated hunts, the repeated association of multiple Deinonychus with single prey animals provides compelling, if circumstantial, evidence for some degree of social behavior among these iconic predators.

Mussaurus: Nursery Evidence

Mussaurus, a relatively small sauropodomorph from the Early Jurassic of Argentina, has provided remarkable evidence of complex social organization through a recently discovered nesting site. Excavations revealed multiple nests containing eggs and hatchlings, juvenile specimens clustered together separate from adults, and adult specimens found in pairs or small groups. This age-segregated spatial arrangement strongly suggests social organization similar to many modern birds and mammals. The clustering of eggs in defined nesting areas indicates communal breeding behavior, while the grouping of similar-aged juveniles suggests “nursery” areas where young animals stayed together, potentially under adult supervision. These findings are particularly significant because they push back the evidence for complex social behavior to the Early Jurassic, approximately 193 million years ago, suggesting that sophisticated social structures evolved relatively early in dinosaur evolution.

Evolutionary Advantages of Herding Behavior

The widespread evidence for herding behavior across multiple dinosaur lineages suggests this social adaptation provided significant evolutionary advantages. Perhaps the most obvious benefit was protection from predators through safety in numbers, as many eyes could detect threats more effectively, and predators would struggle to single out individuals from a large, moving group. Herding also facilitated efficient foraging by allowing groups to collectively locate and exploit food resources, particularly important for large dinosaurs with substantial dietary requirements. Social living likely enhanced reproductive success through communal nesting sites where adults could share predator vigilance duties. For juveniles, herds provided essential protection during vulnerable growth periods and opportunities for social learning of critical survival skills. The fact that herding evolved independently in multiple dinosaur lineages—from sauropods to ceratopsians to hadrosaurs—underscores how powerfully advantageous this social adaptation was within Mesozoic ecosystems.

Modern Parallels: Comparing Dinosaur Herds to Living Animals

The social behaviors observed in dinosaur fossil evidence bear striking similarities to those of many modern animals, providing useful frames of reference for understanding extinct social structures. The massive herds of hadrosaurs like Edmontosaurus have modern parallels in the vast wildebeest or bison herds that offer protection through sheer numbers. The mixed-age groups seen in sauropod trackways resemble the family structures of modern elephants, where adults surround and protect juveniles during movement. The communal nesting behaviors of Maiasaura find parallels in modern crocodiles and many colonial nesting birds. The potential pack hunting behavior of Deinonychus resembles that of wolves or lions, where cooperation enables taking down prey larger than any individual could handle alone. While we must be cautious about making direct comparisons across millions of years of separate evolution, these modern analogs provide valuable models for interpreting the fragmentary evidence of dinosaur sociality preserved in the fossil record.

Conclusion: The Social Lives of Prehistoric Giants

The accumulating evidence for social behavior among dinosaurs has fundamentally transformed our understanding of these ancient creatures. Far from being solitary, cold-blooded reptiles, many dinosaurs appear to have lived in complex social groups that provided protection, enhanced reproductive success and supported the care of young. The diversity of social structures—from the massive herds of hadrosaurs to the family groups of ceratopsians and the potential hunting packs of certain theropods—reveals sophisticated behavioral adaptations comparable to those seen in many modern mammals and birds. These social behaviors likely played crucial roles in the remarkable evolutionary success of dinosaurs, allowing them to dominate terrestrial ecosystems for over 165 million years. As paleontological techniques continue to advance, from CT scanning of fossils to chemical analysis of bones and computer modeling of behaviors, our window into the social lives of these remarkable animals will undoubtedly continue to expand, further enriching our appreciation of dinosaur complexity.