Towering over the Ice Age landscape of North America once prowled a magnificent predator that outmatched even today’s largest big cats. The American lion (Panthera atrox), sometimes called the North American lion, reigned as the continent’s apex predator for hundreds of thousands of years. Weighing up to 800 pounds—nearly 25% larger than modern African lions—these massive felines disappeared approximately 11,000 years ago, leaving behind only fossilized remains and lingering questions. Their extinction represents one of paleontology’s most intriguing mysteries, as these majestic creatures vanished during a period of significant environmental and ecological upheaval. The story of their disappearance offers a fascinating window into prehistoric America and the complex factors that can drive even the mightiest species to extinction.

The Origins and Evolution of Panthera atrox

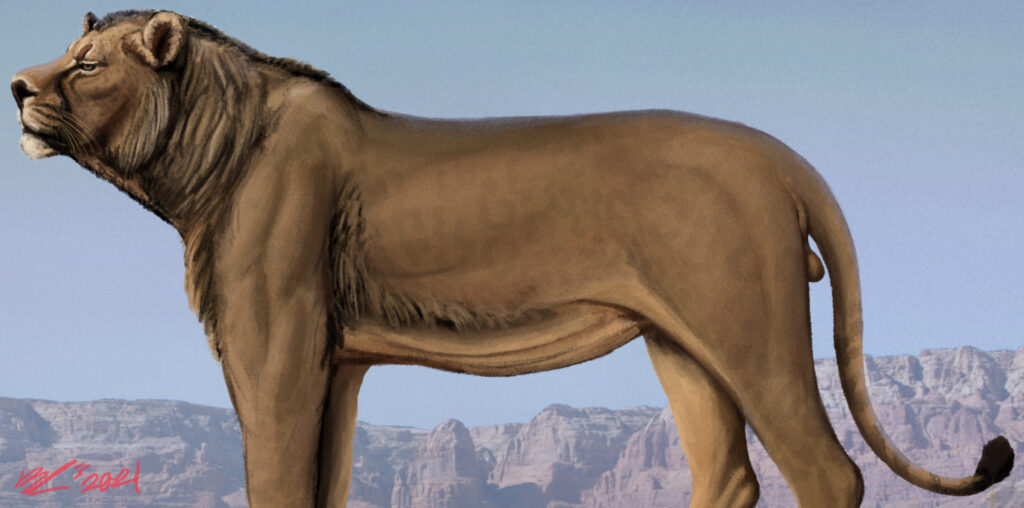

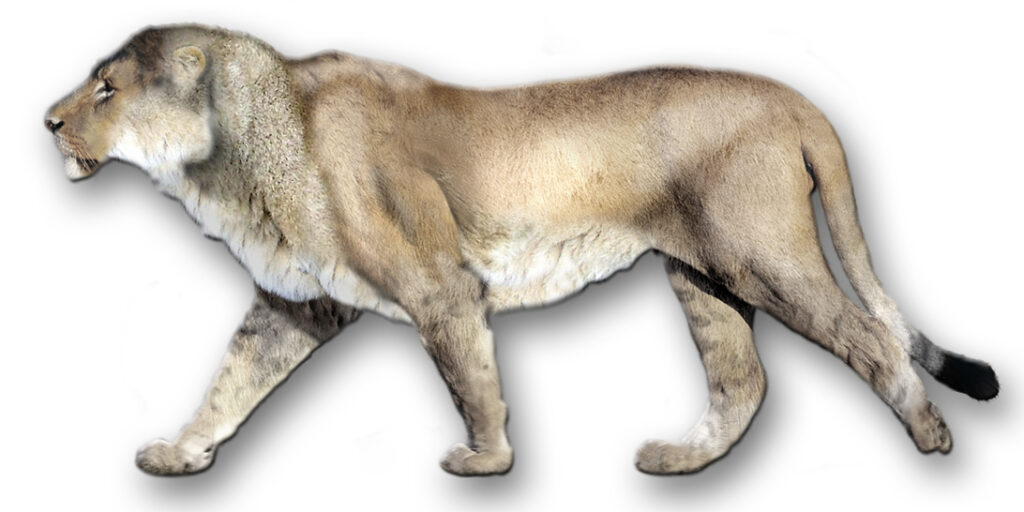

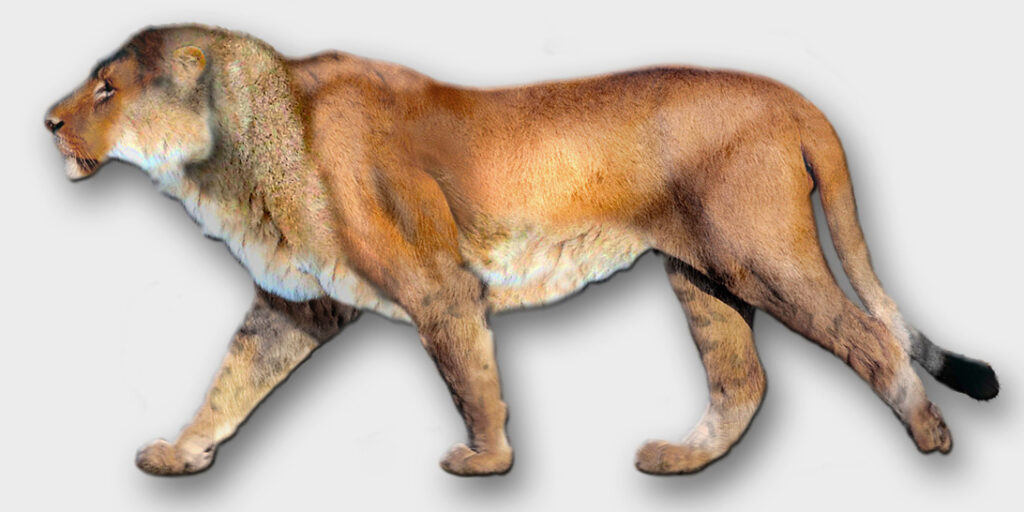

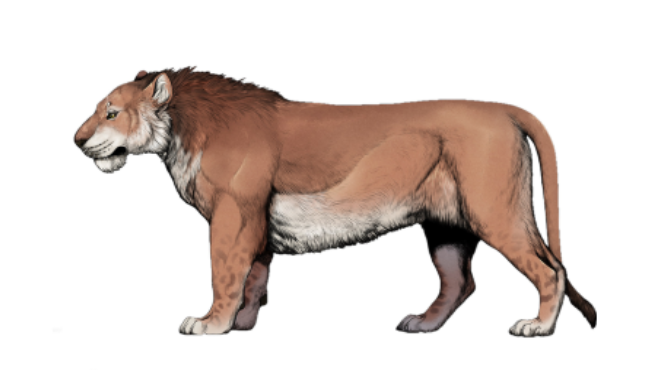

The American lion’s evolutionary journey began approximately 340,000 years ago, descending from ancestors that crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Asia. Genetic studies suggest these cats were more closely related to modern jaguars than African lions, despite their lion-like appearance. As they adapted to North America’s diverse environments, from the Pacific Northwest to Florida and deep into Mexico, they evolved distinct characteristics that set them apart from their Old World cousins. Their massive size, with males reaching lengths of up to 11.5 feet including tail, represented an evolutionary response to the abundance of large prey animals available in Pleistocene North America. The American lion developed longer legs proportional to its body than African lions, suggesting they were built for pursuing prey across open terrain rather than the ambush hunting typical of modern lions.

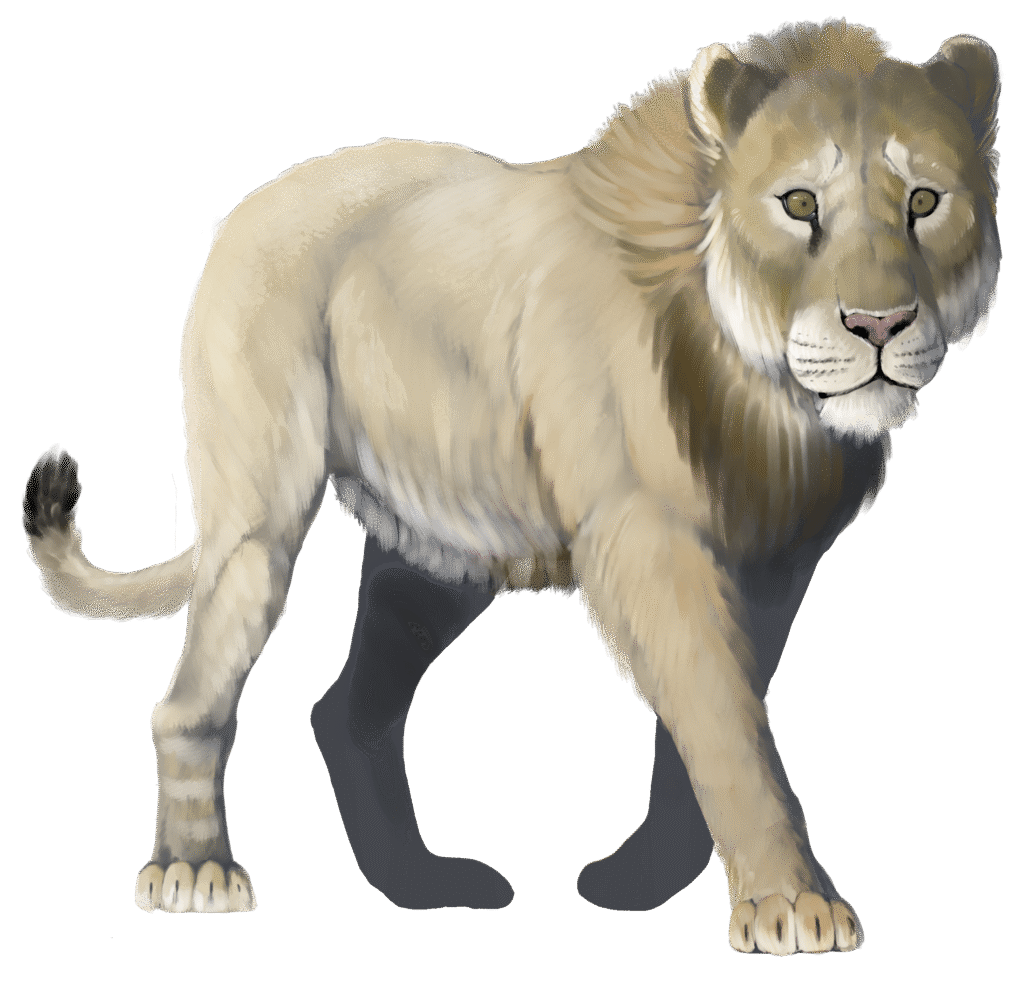

Physical Characteristics of America’s Lost King

Panthera atrox possessed a formidable physique that would have made it immediately recognizable even among today’s impressive big cats. Standing approximately 4 feet tall at the shoulder, these enormous felids featured powerful forelimbs equipped with retractable claws capable of bringing down the largest Ice Age herbivores. Their skulls were notably larger than modern lions’, with jaw muscles and teeth adapted for crushing bone and tearing through tough hides. Unlike African lions, paleontologists believe American lions may have lacked prominent manes based on cave art depictions, though this remains debated. Their pelage likely featured solid coloration suited to the varied environments they inhabited, from grasslands to woodlands. Perhaps most striking was their brain size—about 25% larger than modern lions relative to body size, e—suggesting enhanced cognitive abilities that may have facilitated complex hunting strategies.

The American Lion’s Hunting Prowess

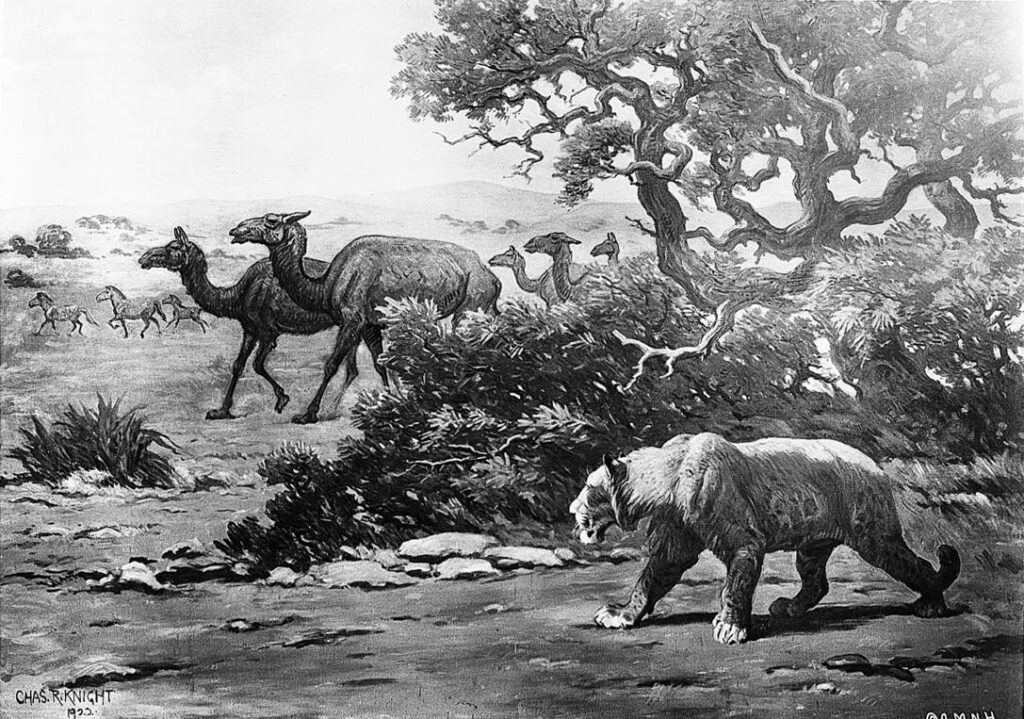

As North America’s dominant predator, the American lion employed hunting strategies tailored to the continent’s megafauna. Evidence from fossil assemblages indicates these cats targeted large herbivores, including bison, horses, ground sloths, young mammoths, and massive camels that once roamed the continent. Their powerful build allowed them to take down prey many times their weight, while their exceptional speed, eed—estimated at up to 50 miles per hour in short bursts, made them formidable pursuit predators. Unlike modern African lions, which typically hunt in prides, evidence suggests American lions may have exhibited more solitary behavior similar to tigers or jaguars. Fossil discoveries at the famous Rancho La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles reveal injuries consistent with the hazardous business of subduing massive prey, indicating these lions regularly risked serious injury to secure meals. Their hunting impact would have significantly shaped prey behavior and plant communities across the landscape, making them true ecosystem engineers.

The Pleistocene Ecosystem: The Lion’s Domain

The American lion thrived in a North America dramatically different from today’s landscape. During the late Pleistocene, the continent hosted an astonishing diversity of megafauna, creating an ecosystem more analogous to modern Africa than contemporary North America. Vast grasslands stretched across the continent’s interior, supporting herds of massive herbivores including several species of now-extinct horses, bison weighing twice as much as modern buffalo, and ground sloths the size of elephants. The American lion shared this productive environment with other apex predators, including dire wolves, short-faced bears, and saber-toothed cats, creating complex competitive dynamics. Seasonal migrations of prey would have influenced lion distribution and behavior, potentially driving seasonal movements similar to those observed in some modern predator populations. This ecosystem represented the pinnacle of mammalian evolution in North America, with animal diversity and average body size exceeding anything seen on the continent today.

Distribution and Habitat Range

The American lion boasted one of the most extensive ranges of any big cat in history, with fossils discovered from Alaska to Peru. This remarkable distribution demonstrates their adaptability to diverse climatic conditions and ecological niches. In North America, their remains have been found from coast to coast, with significant concentrations in California, Texas, and the Great Plains. The cats appear to have preferred open grasslands and mixed woodland-savanna environments where visibility facilitated hunting large prey, though they adapted to more varied landscapes as needed. Their northernmost populations in Alaska and the Yukon coexisted with cold-adapted species like woolly mammoths and musk oxen, suggesting these lions developed physiological adaptations to survive harsh winter conditions. Unlike many Ice Age mammals that retreated southward during glacial periods, evidence indicates American lions maintained northern populations even during climatic minima, demonstrating remarkable cold tolerance for a large felid.

Social Structure and Behavior Theories

The social dynamics of American lions remain largely speculative, presenting one of paleontology’s most intriguing mysteries. While modern African lions are known for their complex pride structure, American lions may have exhibited different social arrangements. The relative scarcity of American lion fossils compared to other predators at sites like Rancho La Brea suggests they might have been more solitary hunters like modern tigers or jaguars. Sexual dimorphism in American lions appears less pronounced than in African lions, which might indicate reduced male competition for females and possibly different mating systems. Some researchers hypothesize American lions formed loose associations during certain seasons or for specific hunting opportunities rather than maintaining year-round prides. Cave paintings from the Late Pleistocene occasionally depict groups of large cats, potentially representing American lions in social gatherings, though interpretation remains challenging. Whatever their social structure, it would have been adapted to the unique ecological conditions of Pleistocene North America.

Ancient Encounters: Humans and American Lions

The relationship between early humans and American lions represents a fascinating chapter in North American prehistory. Paleolithic people arrived in North America at least 16,000 years ago, meaning they coexisted with these massive predators for several thousand years before the lions’ extinction. Cave paintings discovered in Europe depict lions similar to Panthera atrox, suggesting these cats left significant impressions on human consciousness wherever they were encountered. Archaeological evidence occasionally reveals lion remains with butchery marks, indicating humans sometimes hunted these dangerous predators, likely for their pelts or as ritual demonstrations of prowess. Conversely, rare human remains show evidence of large cat predation, suggesting American lions occasionally viewed humans as potential prey. This complex predator-prey dynamic may have influenced early human settlement patterns in North America, with lion territories potentially avoided by smaller human groups lacking sufficient defenses against such formidable predators.

Leading Theories on Extinction Causes

The disappearance of the American lion coincided with the broader Quaternary extinction event that eliminated approximately 80% of North America’s large mammals around 11,000-13,000 years ago. Climate change represents one primary extinction hypothesis, as the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene brought rapid warming and ecosystem transformations that may have reduced suitable habitat and prey availability. The overkill or blitzkrieg hypothesis suggests human hunters, newly arrived in North America, might have directly hunted lions or, more likely, decimated their prey base through efficient hunting of herbivores. Disease introduction presents another possibility, as humans and their domesticated animals may have carried pathogens to which native species had no immunity. Most paleontologists now favor a multiple-causation model where climate change stressed lion populations while human hunting activities further reduced prey availability, creating a perfect storm of extinction pressures that even these mighty predators couldn’t survive.

The Cascade Effect: Ecological Impact of Disappearance

The extinction of the American lion triggered profound ripple effects throughout North American ecosystems that continue to influence the continent’s ecology today. As apex predators, these lions would have regulated herbivore populations through direct predation and behavioral effects, preventing overgrazing and maintaining vegetation diversity. Their disappearance likely allowed surviving herbivores like white-tailed deer to dramatically increase in abundance and alter their behavior in the absence of predation pressure. The loss of the continent’s largest cat created a vacancy in the apex predator niche that was partially filled by smaller native cats like cougars and immigrant species like gray wolves, though neither could fully replicate the ecological role of such a massive predator. Vegetation patterns across North America shifted significantly after the Pleistocene extinctions, with some plant communities dependent on the ecosystem engineering effects of megafauna and their predators declining dramatically. These cascading ecological changes following the lion’s disappearance represent one of history’s most significant examples of how predator loss can transform entire landscapes.

Fossil Discoveries and Scientific Understanding

Our knowledge of American lions has been pieced together through remarkable fossil discoveries across the continent. The most significant collection comes from the Rancho La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles, where over 80 individual lions have been recovered from the asphaltic deposits that trapped and preserved animals over millennia. The La Brea specimens provide unprecedented insights into lion anatomy, population structure, and even pathologies and injuries sustained during life. Important discoveries have also emerged from Natural Trap Cave in Wyoming, where animals fell into a natural pitfall cave and were preserved in exceptional condition. Genomic research has revolutionized our understanding of the American lion’s evolutionary relationships, with ancient DNA analysis revealing its close genetic affinity to jaguars rather than African lions as previously assumed based on morphology alone. New analytical techniques, including stable isotope analysis of bones and teeth, continue to reveal details about lion diet, geographic range, and seasonal behavior patterns that were previously inaccessible to researchers.

The American Lion in Cultural Imagination

Though extinct for millennia, the American lion continues to capture human imagination as a symbol of wild North America’s lost grandeur. Native American oral traditions across the continent include stories of enormous cats that may represent cultural memories of encounters with these impressive predators. Early European naturalists encountered jaguar populations in the southern United States but were unaware of the much larger feline that had preceded them. The discovery of American lion fossils in the 19th century sparked public fascination with extinct North American megafauna, contributing to the development of paleontology as a scientific discipline. In contemporary culture, the American lion frequently appears in museum exhibitions, nature documentaries, and paleoart reconstructions that attempt to bring this magnificent animal back to life in the public imagination. Conservation biologists sometimes reference the ecological vacancy left by the American lion when discussing rewilding initiatives and the potential reintroduction of large predators to North American ecosystems.

Modern Parallels: Conservation Lessons

The extinction of the American lion offers sobering parallels to modern conservation challenges facing the world’s remaining big cats. All seven living big cat species face significant threats from habitat loss, human conflict, and poaching, echoing some of the same pressures that likely contributed to the American lion’s demise. The vulnerability of even the most powerful predators to environmental change and human activities has been repeatedly demonstrated across time. Lion conservation efforts in Africa and Asia today employ strategies that might have benefited American lions had they been implemented 13,000 years ago, including habitat corridors, prey protection, and human-wildlife conflict mitigation. The American lion’s disappearance serves as a powerful reminder that even the most successful evolutionary lineages can vanish when environmental changes outpace adaptive capacity. Perhaps most importantly, the extinction of North America’s largest cat demonstrates how quickly keystone species can be lost and the profound, often irreversible ecological consequences that follow.

The Future of Big Cat Evolutionary Biology

The study of American lions continues to advance through emerging technologies and methodologies that offer new windows into the past. Ancient DNA techniques now allow scientists to sequence portions of the American lion genome from well-preserved specimens, providing unprecedented insights into their evolutionary history and genetic diversity before extinction. Cutting-edge anatomical modeling allows researchers to reconstruct American lion locomotion, hunting behaviors, and biomechanical capabilities with increasing precision. Climate proxies derived from ice cores, lake sediments, and other sources help contextualize lion extinction within broader environmental changes occurring during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. These scientific advances carry implications beyond academic interest, potentially informing conservation strategies for surviving big cats by identifying genetic, behavioral, and ecological factors that enhance resilience against extinction threats. The American lion serves as both a warning and a laboratory for understanding how large predators respond to environmental change, offering lessons that may prove crucial for preserving Earth’s remaining big cats in an era of accelerating human impacts and climate disruption.

The Rise and Fall of the American Lion

As we piece together the story of the American lion’s rise and fall, we confront a bittersweet reality: North America once supported predators that rivaled or exceeded the most impressive carnivores alive today. The loss of Panthera atrox represents not just the disappearance of a species but the unraveling of ecological relationships developed over hundreds of thousands of years. Though we will never again witness these magnificent cats prowling the North American landscape, scientific investigation continues to bring their story into sharper focus, allowing us to appreciate their evolutionary achievements and understand the complex factors that led to their demise. In doing so, we gain valuable perspectives on our relationship with the natural world and the responsibility we bear toward the remaining great predators that still inhabit our planet’s wild places.