In the world of paleontology, few discoveries capture the imagination quite like fossilized dinosaurs preserved in dynamic poses. These remarkable specimens, sometimes called “dancing dinosaurs,” offer rare glimpses into prehistoric behavior frozen in time.

Unlike typical fossils showing animals at rest, these exceptional finds depict dinosaurs seemingly caught mid-action—fighting, fleeing, protecting young, or even mating. Such fossils provide unprecedented insights into dinosaur behavior, biology, and ecology that static remains simply cannot reveal.

Let’s explore the fascinating world of these action-captured dinosaur fossils and what they teach us about life in the Mesozoic Era.

The Phenomenon of Action-Preserved Fossils

Action-preserved fossils represent extraordinarily rare circumstances where animals were rapidly entombed during active behaviors. These specimens require perfect preservation conditions, typically involving sudden burial by volcanic ash, sand storms, or mud flows that can instantly capture creatures in their final moments.

The scientific term “behavioral fossils” applies to these unique finds, where posture and positioning reveal information about what the animal was doing at its moment of death. Unlike traditional fossils that merely show anatomy, these action poses serve as prehistoric snapshots, providing direct evidence of behaviors scientists would otherwise only speculate about. The dramatic nature of these posed fossils often creates visually striking specimens that appear to tell stories from millions of years ago.

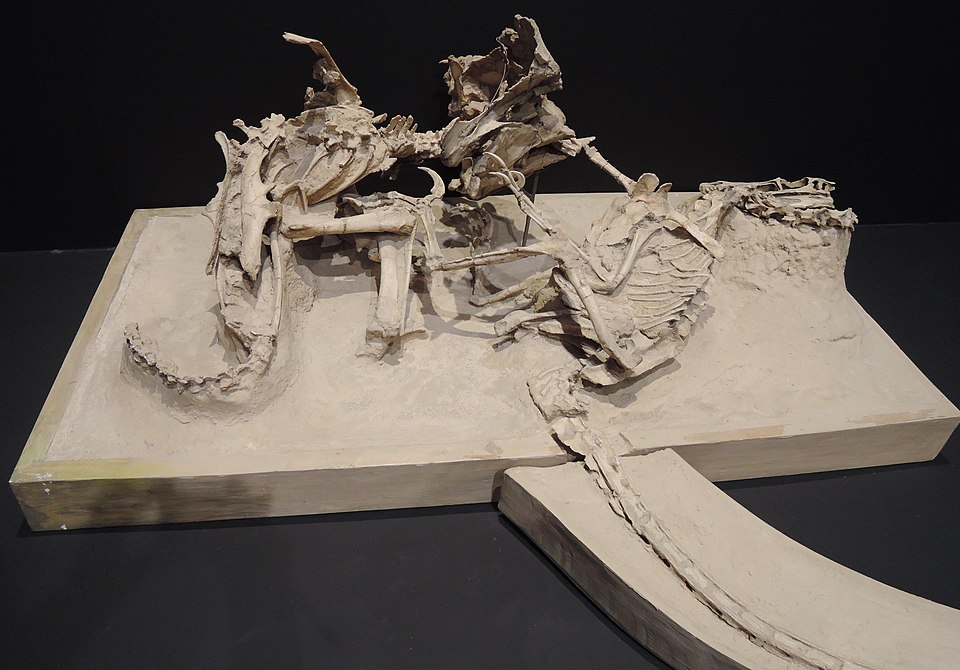

The Famous Fighting Dinosaurs

Perhaps the most iconic example of dinosaurs caught in action is the “Fighting Dinosaurs” specimen discovered in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert in 1971. This extraordinary fossil shows a Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in mortal combat, preserved exactly as they died approximately 80 million years ago. The Velociraptor’s sickle claw is positioned at the Protoceratops’ neck, while the Protoceratops appears to have the predator’s right arm clamped in its beak.

Scientists believe a sudden sandstorm or collapsing sand dune entombed these combatants mid-fight, preserving what represents the most dramatic evidence of predator-prey interaction in the fossil record. This specimen single-handedly transformed our understanding of Velociraptor hunting techniques and Protoceratops defensive behaviors, providing direct evidence that these species interacted as predator and prey.

The Sleeping Dragon: Mei long

In 2004, paleontologists working in China’s Liaoning Province discovered a small troodontid dinosaur preserved in a remarkably lifelike sleeping position. Named Mei long (meaning “soundly sleeping dragon”), this specimen shows the animal curled up with its head tucked under its arm, precisely mimicking the sleeping posture of modern birds.

The fossil reveals the dinosaur was resting when suddenly buried by volcanic ash, preserving even delicate details like its feather impressions. This discovery provides compelling evidence for bird-like sleeping behaviors in non-avian dinosaurs, strengthening the evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and modern birds. Moreover, the specimen suggests this sleeping posture evolved for heat conservation long before the origin of birds, representing an adaptation developed by small-bodied, warm-blooded dinosaurs millions of years earlier.

The Dueling Dinosaurs

One of the most spectacular recent discoveries in paleontology is the “Dueling Dinosaurs” specimen found in Montana in 2006. This extraordinary fossil preserves what appears to be a Tyrannosaurus rex and a Triceratops engaged in battle, both preserved in three dimensions with skin impressions and even stomach contents intact. The specimen suggests these mortal enemies died together, possibly when their battleground collapsed into mud or quicksand.

After years of legal battles regarding ownership, the specimen was finally acquired by the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in 2020 for further study. Paleontologists are particularly excited about this specimen because both dinosaurs appear to be complete, with minimal crushing and exceptional preservation of soft tissues. The ongoing research promises to reveal unprecedented details about these iconic dinosaur species and their interactions.

Nesting Behaviors Frozen in Time

Some of the most emotionally evocative action fossils depict dinosaurs engaged in parental care. The “Big Mama” specimen, an oviraptorid dinosaur discovered in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, shows an adult positioned directly over its nest of eggs in a protective brooding posture. Initially misinterpreted as a dinosaur caught in the act of stealing eggs (hence the name “oviraptor” or “egg thief”), scientists now recognize this and similar specimens as evidence of bird-like nesting behaviors.

Multiple examples of oviraptorids preserved while brooding their nests demonstrate that these dinosaurs died protecting their offspring, often during sandstorms. These fossils provide definitive evidence that many theropod dinosaurs were attentive parents, contradicting earlier assumptions about reptilian neglect. The positioning of the adult’s limbs spread over the nest suggests these dinosaurs used their feathered arms to shelter their eggs, much as modern birds do.

Death Poses: Understanding the Contorted Postures

Many dinosaur fossils exhibit dramatic, contorted postures that were once mistakenly interpreted as capturing the animal’s final struggles. The classic “death pose” with head arched back, tail extended, and limbs contracted was long thought to indicate suffering or agonizing final moments. However, modern research has revealed that these positions typically result from post-mortem processes rather than behavioral capture.

When animals die, the ligaments and tendons along their spine naturally contract as they dry out, pulling the head and tail backward in what scientists call the opisthotonic pose. This phenomenon occurs in everything from chickens to humans and explains many dramatic fossil postures without requiring the animal to have died in action. Distinguishing between true behavioral fossils and post-mortem positioning represents one of the key challenges in interpreting apparently active dinosaur poses.

The Science of Taphonomy: How Action Gets Preserved

The study of how organisms become fossilized, known as taphonomy, helps explain the rarity and significance of action-preserved dinosaurs. For behavior to be captured in the fossil record, several unlikely events must occur simultaneously. First, the animal must die during the behavior itself rather than beforehand or afterward. Second, burial must happen extraordinarily quickly—within hours rather than days—before scavengers or decomposition disrupt the positioning.

Third, the sediment must be fine-grained enough to capture details but substantial enough to prevent disturbance. Finally, the fossil must survive millions of years of geological processes without being crushed, eroded, or otherwise damaged. Taphonomists estimate that fewer than one in a million fossils preserve any behavioral information, making each action-captured dinosaur an extraordinary scientific treasure.

The Running Dinosaurs of Germany

In 1998, excavations at the Münchehagen tracksite in Germany revealed something unprecedented: perfectly preserved dinosaur footprints showing multiple bipedal dinosaurs running in the same direction. Unlike single footprints or walking trails, these tracks captured a moment when several medium-sized theropods were sprinting at speeds estimated at over 25 miles per hour.

The depth and spacing of the footprints allowed scientists to calculate the dinosaurs’ speed, stride length, and even their approximate weight. Most intriguingly, the parallel nature of the tracks suggests coordinated movement, potentially representing evidence of pack behavior. The Münchehagen trackway provides rare evidence of dinosaur locomotion during high-speed movement, offering insights into their athletic capabilities that skeletal remains alone could never reveal.

Dinosaurs Caught Swimming

Astonishing trackways discovered in Wyoming’s Bighorn Canyon reveal dinosaurs engaged in an unexpected behavior: swimming. These unique traces show partial footprints and drag marks where the animals’ feet occasionally touched the bottom while their bodies remained buoyant in water. Scientists can distinguish swimming tracks from walking tracks by their irregular pattern and reduced pressure, as the animal’s weight was supported by water.

One particularly remarkable trackway shows a theropod dinosaur swimming across what was once a shallow lake, occasionally pushing off the bottom with its powerful hind limbs. These rare swimming traces contradict earlier assumptions that large dinosaurs avoided deep water and demonstrate that at least some species were comfortable and capable swimmers. The finding expands our understanding of dinosaur habitat use and behavioral adaptability.

The Mating Dinosaurs Controversy

In 2012, paleontologists in Mongolia described a potential first in the fossil record: two oviraptorids apparently preserved while mating. The specimen shows two similar-sized individuals positioned close together in a manner reminiscent of modern bird mating positions. The researchers suggested the dinosaurs were caught in the act when buried by a collapsing sand dune. However, this interpretation has proven controversial among scientists, with many experts arguing that the positioning could result from other factors, including the coincidental burial of two individuals or taphonomic processes that brought the bodies together post-mortem.

The scientific debate surrounding this specimen highlights the challenges in interpreting behavioral fossils, particularly for behaviors that leave little skeletal evidence. If confirmed, this would represent the only direct evidence of dinosaur reproductive behavior in the fossil record, but the scientific community remains divided about the specimen’s significance.

Interpreting Fossil Behavior: Science or Speculation?

The study of behavioral fossils walks a fine line between evidence-based interpretation and speculative storytelling. Paleontologists must consider multiple alternative explanations for any seemingly action-oriented fossil positioning. Was a dinosaur truly running when preserved, or were its legs positioned that way after death? Does a group burial represent social behavior, or simply multiple animals caught in the same catastrophic event?

Scientists use several approaches to strengthen behavioral interpretations, including comparative anatomy with living relatives, biomechanical analysis, and taphonomic experiments with modern animals. Additionally, repeated examples of similar positioning across multiple specimens provide stronger evidence for behavioral interpretations. Despite these scientific approaches, some degree of uncertainty always remains when interpreting behavior from fossils, making these specimens both scientifically valuable and perpetually debatable.

Modern Technologies Revealing Ancient Actions

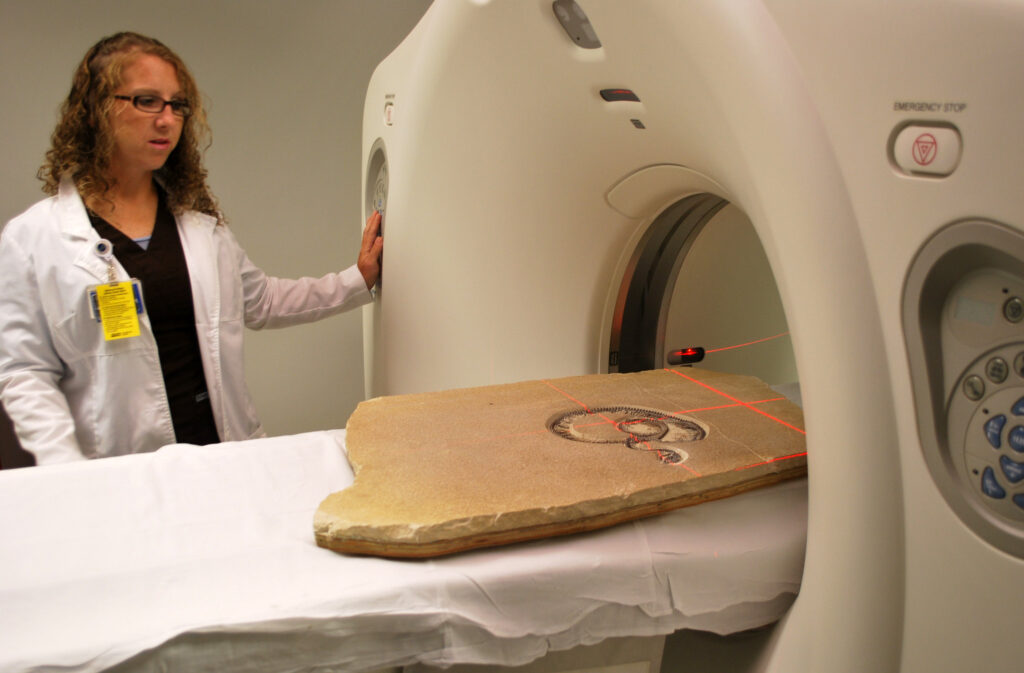

Advanced technologies are revolutionizing how scientists study action-preserved dinosaurs, revealing details invisible to previous generations of researchers. CT scanning allows paleontologists to examine the internal structure of fossils without damaging them, potentially revealing meal remains, egg structures, or muscle attachments relevant to the preserved behavior. Laser surface scanning creates precise three-dimensional models that can be digitally manipulated to test biomechanical hypotheses about the feasibility of captured poses.

Synchrotron imaging can detect chemical residues that might indicate stress hormones or other physiological states at the moment of death. These non-destructive techniques allow for increasingly sophisticated analysis of behavioral fossils, often revealing that specimens discovered decades ago still contain untapped information about dinosaur behavior. As technology advances, paleontologists continue to extract new insights from these rare action-preserved specimens.

The Future of Behavioral Paleontology

The study of dinosaurs caught in action represents a growing field within paleontology, with new discoveries and methodologies continuing to emerge. Expedition teams now specifically target geological formations with conditions favorable to rapid burial and exceptional preservation, increasing the chances of finding behaviorally informative fossils. Computer modeling allows scientists to simulate dinosaur movements and test whether preserved positions represent physically possible behaviors.

Some researchers are developing new approaches to distinguish between truly behavioral fossils and those with misleading post-mortem positioning. The integration of paleontology with comparative biology, biomechanics, and taphonomic experimentation promises increasingly rigorous interpretations of dinosaur behavior. As new specimens emerge from unexplored regions and technologies advance, our understanding of dinosaur behavior will continue to evolve, bringing these ancient animals to life in increasingly vivid and scientifically grounded ways.

Conclusion

The rare and spectacular fossils of dinosaurs caught in action provide invaluable windows into the dynamic lives of creatures that dominated Earth for over 160 million years. From fighting predators and protective parents to running herds and swimming individuals, these exceptional specimens transform our understanding of dinosaurs from static skeletons to living, breathing animals with complex behaviors.

While interpreting these fossils presents significant scientific challenges, each action-preserved specimen adds another piece to the puzzle of prehistoric life. As we continue to unearth and study these remarkable time capsules, the dancing dinosaurs will keep revealing their ancient secrets, helping us understand not just what these magnificent creatures looked like but how they lived, moved, and interacted in their long-vanished world.