Few prehistoric predators have captured the modern imagination quite like the dire wolf. Made famous by George R.R. Martin’s fantasy series “A Song of Ice and Fire” and its television adaptation “Game of Thrones,” dire wolves have transcended from paleontological curiosity to pop culture icon. However, the fictional portrayal differs significantly from what science tells us about Canis dirus, the “fearsome dog” that once roamed North America. Recent groundbreaking research has revolutionized our understanding of this extinct canid, revealing surprising truths about its biology, behavior, and evolutionary history. This article separates fact from fiction, exploring the real dire wolf’s place in natural history, its relationship to modern wolves, and examines whether de-extinction technologies might one day bring this magnificent predator back from extinction.

The True Identity of Canis dirus

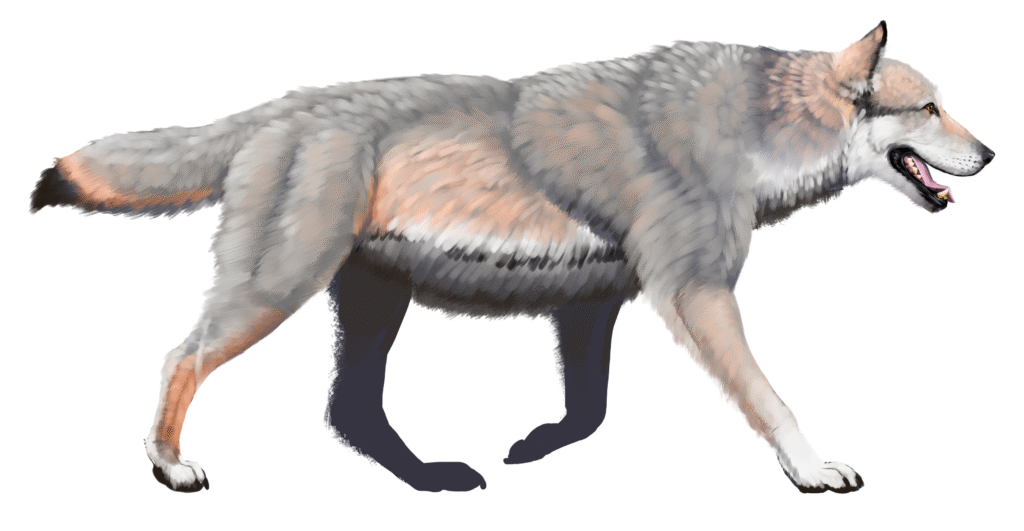

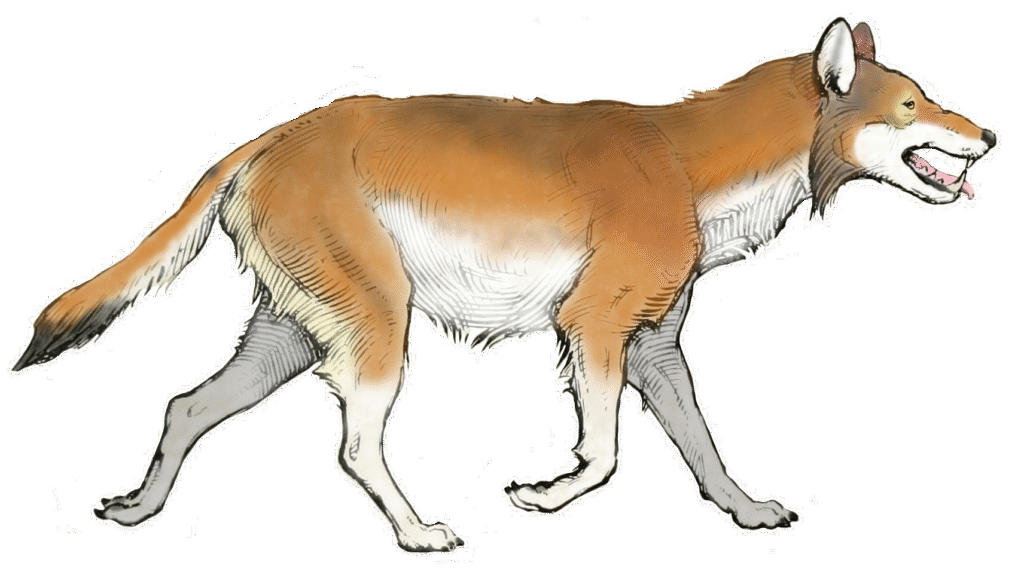

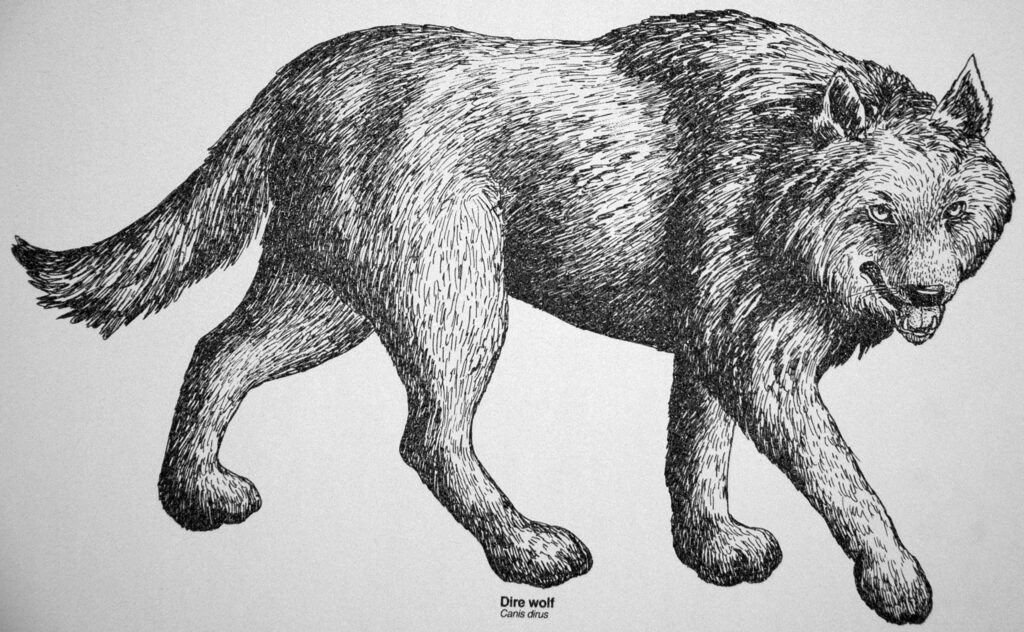

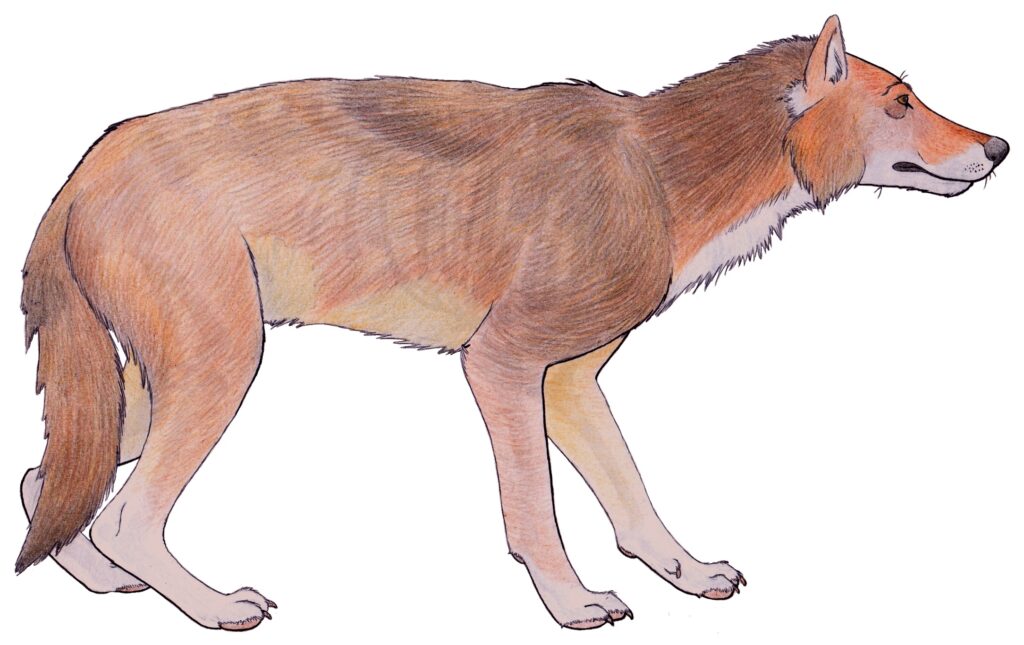

The dire wolf (Canis dirus) was a large canid that lived approximately 125,000 to 9,500 years ago during the Late Pleistocene epoch. Unlike its fantasy counterpart, which is portrayed as a supersized version of the gray wolf, the real dire wolf was a distinct species with its evolutionary trajectory. Standing about 31 inches at the shoulder and weighing between 130 and 150 pounds, dire wolves were larger than most modern wolves, but not dramatically. Their most distinctive features were their robust skulls and powerful jaws, which were adapted for crushing bone and processing tough prey. Paleontologists have recovered thousands of dire wolf specimens, particularly from the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, making it one of the best-studied prehistoric carnivores in North America.

Evolutionary History: A Canid Surprise

In January 2021, a groundbreaking study published in Nature fundamentally changed our understanding of dire wolf evolution. By analyzing ancient DNA extracted from dire wolf fossils, researchers discovered that dire wolves were not closely related to gray wolves as previously thought. Instead, they belonged to a distinct lineage that had been evolving separately from gray wolves and coyotes for approximately 5.7 million years. This revelation places dire wolves in their genus, Aenocyon (“terrible wolf”), rather than Canis. The genetic evidence suggests that, despite physical similarities to gray wolves—an example of convergent evolution—dire wolves were as different from gray wolves as modern humans are from chimpanzees. This evolutionary distance explains why, unlike other North American canids that interbred during the Pleistocene, dire wolves remained genetically isolated.

Habitat and Distribution

Dire wolves thrived across a vast geographical range that spanned from Canada to South America, with their population center in the southern United States. They were particularly abundant in what is now California, Texas, and Mexico, as evidenced by the rich fossil record. Unlike the fantasy portrayal that associates dire wolves with frozen northern landscapes, the real dire wolves preferred warmer climates and open grasslands or mixed woodlands. They coexisted with gray wolves in some regions, though the two species likely occupied different ecological niches to minimize competition. Their wide distribution across diverse environments demonstrates the dire wolf’s adaptability and success as a predator for over 100,000 years before its ultimate extinction.

Hunting and Feeding Behavior

The dire wolf was an apex predator specialized for hunting large herbivores of the Pleistocene epoch. Their robust skull, powerful jaw muscles, and specialized carnassial teeth suggest they were formidable hunters capable of bringing down large prey like bison, horses, ground sloths, and possibly young mammoths or mastodons. Studies of wear patterns on their teeth indicate a diet consisting primarily of large ungulates. Unlike their portrayal in fiction as solitary hunters, evidence suggests dire wolves likely hunted in packs similar to modern wolves, allowing them to tackle larger prey than would be possible individually. Isotopic analyses of dire wolf remains from the La Brea Tar Pits reveal they specialized in hunting horses and bison, demonstrating a different dietary niche than contemporary predators like saber-toothed cats, which focused on larger herbivores.

Social Structure: Pack Dynamics

Though direct observation of dire wolf behavior is impossible, scientists can make educated inferences about their social structure based on fossil evidence and comparison with modern canids. The high number of specimens found in predator traps like the La Brea Tar Pits suggests dire wolves hunted in groups, as multiple individuals were often lured to the same dying prey animal stuck in the asphalt. Skeletal evidence reveals healed injuries that would have been debilitating without pack support, suggesting social care similar to that observed in modern wolf packs. The dire wolf’s brain case, while proportionally smaller than that of gray wolves, was still large enough to support complex social behaviors. Pack hunting would have been advantageous for bringing down the large Pleistocene herbivores that formed their primary prey base, further supporting the theory that dire wolves lived in family groups with cooperative social structures.

Physical Differences from Modern Wolves

Despite superficial similarities, dire wolves differed from gray wolves in several important anatomical aspects. The dire wolf possessed a broader, more powerful skull with larger teeth adapted for bone-crushing and meat-shearing. Their legs were proportionally shorter and more robust, suggesting they were built more for strength and endurance rather than the speed and agility that characterize modern wolves. The dire wolf’s chest was deeper and broader, housing larger lungs and a heart to power their muscular frame. Recent morphological studies indicate dire wolves had different jaw mechanics that provided greater bite force at the expense of jaw flexibility. Their molars show greater wear than those of gray wolves, indicating they consumed more bone and tougher materials as part of their regular diet. These physical differences reflect the dire wolf’s adaptation to hunting the megafauna of the Pleistocene, a niche that no longer exists in North America.

Extinction: The End of an Era

The dire wolf disappeared approximately 9,500 years ago, making it one of the casualties of the Late Pleistocene extinction event that claimed many North American megafauna species. Unlike the gray wolf, which survived this extinction bottleneck, the dire wolf’s specialized adaptations may have contributed to its downfall. The disappearance of their preferred large prey species, combined with climate change at the end of the last ice age, drastically altered their habitat and food sources. Competition with gray wolves and other surviving predators likely exacerbated their struggle. Their genetic isolation, now confirmed by DNA evidence, meant dire wolves couldn’t hybridize with other canids to introduce potentially beneficial adaptations, unlike gray wolves and coyotes, which interbred and showed greater genetic flexibility. The dire wolf’s extinction represents a cautionary tale about evolutionary specialization and the vulnerability of even apex predators to rapid environmental change.

Game of Thrones: Fiction vs. Reality

HBO’s “Game of Thrones” catapulted dire wolves into popular culture, portraying them as extraordinarily large, intelligent companions to the Stark family. These fictional dire wolves, while captivating, bear little resemblance to their real-world counterparts. The show’s dire wolves were initially portrayed by Northern Inuit dogs, a wolfdog breed, before being replaced with CGI as the characters grew larger. In the fictional world, dire wolves are depicted as standing as tall as a horse and possessing almost supernatural intelligence and loyalty. Real dire wolves, while impressive predators, were only marginally larger than modern gray wolves and lacked the close evolutionary relationship to modern wolves suggested in the series. The show’s portrayal of dire wolves surviving north of a massive ice wall ironically contrasts with scientific evidence that real dire wolves preferred warmer southern habitats. Despite these inaccuracies, the cultural impact of Martin’s dire wolves has undeniably sparked public interest in the actual prehistoric species.

De-Extinction: Science or Science Fiction?

The concept of resurrecting extinct species through genetic engineering has gained traction in recent years, with projects aimed at reviving the woolly mammoth and passenger pigeon already underway. However, the dire wolf presents unique challenges for potential de-extinction efforts. The 2021 genetic study revealing the dire wolf’s evolutionary distance from modern canids complicates matters significantly. Without a close living relative to provide a complete genomic template, scientists would need to sequence and reconstruct the entire dire wolf genome from ancient DNA, which degrades over time. Even if a complete genome could be assembled, creating a viable embryo would require a suitable surrogate species—possibly a gray wolf, though the genetic differences might cause developmental incompatibilities. Ethical questions also arise about bringing back a predator adapted to hunting large mammals in ecosystems that have evolved without them for thousands of years. While technically not impossible, dire wolf de-extinction remains firmly in the realm of theoretical possibility rather than imminent reality.

Modern Research Methods: Unlocking Ancient Secrets

Advancements in paleontological techniques have revolutionized our understanding of dire wolves in recent years. Beyond traditional morphological studies of fossils, scientists now employ sophisticated methods like ancient DNA analysis, isotope studies, and 3D morphometrics to uncover new insights. The groundbreaking 2021 genetic study utilized next-generation sequencing to extract and analyze DNA from dire wolf fossils up to 50,000 years old, overcoming the challenges of working with degraded genetic material. Stable isotope analysis of dire wolf teeth and bones has revealed detailed information about their diet and habitat preferences. CT scanning and computational biomechanics have allowed researchers to model how dire wolves moved and hunted, including calculations of bite force and running capabilities. Comparative genomics with other canid species has illuminated the dire wolf’s unique evolutionary pathway and the genetic adaptations that made it successful during the Pleistocene. These sophisticated techniques continue to reveal new aspects of dire wolf biology, allowing scientists to reconstruct their lives with unprecedented detail.

Cultural Impact Through History

Long before “Game of Thrones,” the dire wolf had carved out a place in human cultural awareness. The species was first scientifically described in 1858 by Joseph Leidy based on fossils found in Indiana, capturing scientific interest during the early development of paleontology in North America. The La Brea Tar Pits, discovered in the early 20th century, brought dire wolves to broader public attention as thousands of specimens were excavated, making them a centerpiece of museum exhibitions nationwide. The name “dire wolf” itself entered popular imagination through various fantasy and speculative works throughout the 20th century. Beyond Martin’s series, dire wolves have appeared in multiple books, films, and games, often with exaggerated size and abilities. This cultural fascination reflects humanity’s enduring interest in apex predators and particularly those we never had to face. The dire wolf’s status as an extinct North American predator allows it to occupy a unique space in our collective imagination—familiar enough to resonate with our understanding of wolves, yet distant enough to be mythologized.

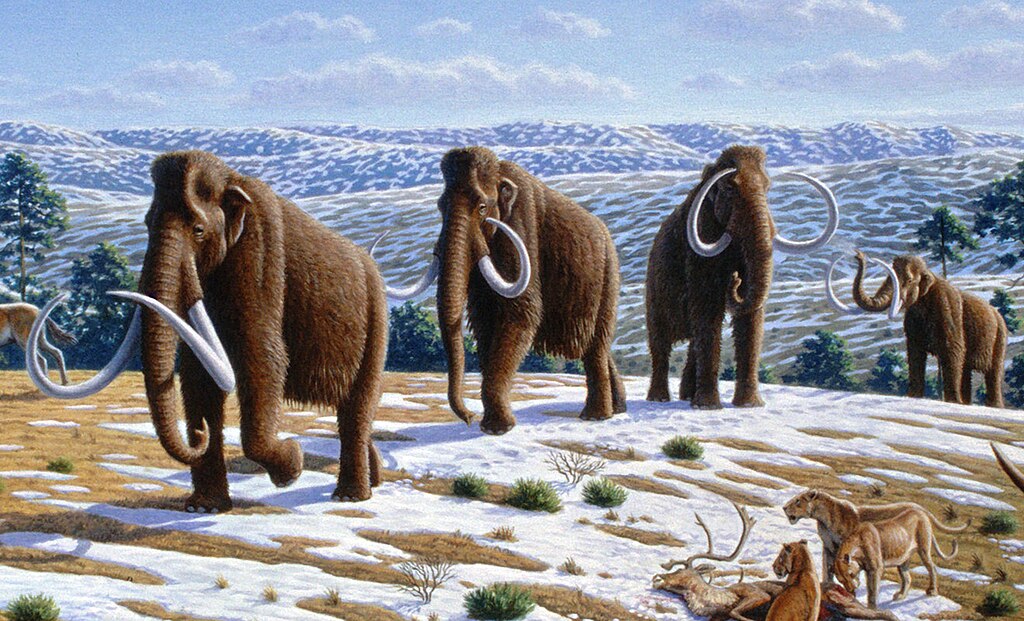

Dire Wolves and the Greater Pleistocene Ecosystem

Dire wolves existed within a complex and dramatically different ecosystem than that of modern North America. They shared their environment with an astonishing diversity of megafauna, including mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, American lions, short-faced bears, and saber-toothed cats. In this predator-rich landscape, dire wolves likely carved out a specific ecological niche, possibly focusing on medium-sized herbivores or scavenging from kills made by larger predators. The presence of multiple large carnivores suggests a productive ecosystem with abundant prey resources to support these predatory populations. Fossil evidence indicates dire wolves frequently competed directly with other predators, as shown by tooth puncture marks on bones suggesting competitive scavenging. The disappearance of dire wolves coincided with a broader collapse of this megafaunal ecosystem at the end of the Pleistocene, potentially triggered by a combination of climate change and the arrival of human hunters in North America. Understanding the dire wolf’s role in this extinct ecosystem provides valuable insights into predator-prey dynamics and ecological stability across evolutionary timeframes.

Lessons from the Dire Wolf’s Extinction

The dire wolf’s extinction offers valuable insights relevant to modern conservation efforts. As a highly specialized apex predator, the dire wolf demonstrates how specialization can be both an evolutionary advantage during stable periods and a liability during rapid environmental change. Unlike the more adaptable gray wolf, the dire wolf’s specialized hunting strategies and dietary requirements likely contributed to its inability to survive the end-Pleistocene upheaval. The confirmed lack of hybridization with other canids suggests genetic isolation limited the dire wolf’s adaptive capacity, contrasting with modern wolves and coyotes, whose genetic exchange has facilitated adaptation to changing conditions. Today’s endangered species, particularly large carnivores with specialized diets or habitat requirements, face similar vulnerabilities as environments change rapidly due to human activity. The dire wolf’s extinction reminds us that even successful species that dominated their ecosystems for thousands of years can vanish when conditions change beyond their adaptive capacity. For modern conservation biologists, the dire wolf represents both a warning about specialization risks and an example of how genetics influences adaptive potential.

The Future of Dire Wolf Research

The field of dire wolf research stands at an exciting crossroads, with new technologies promising to unlock further secrets about this iconic predator. As ancient DNA sequencing techniques continue to improve, researchers hope to recover more complete genomic information from dire wolf remains, potentially allowing for a complete genome assembly in the coming years. This would provide unprecedented insights into the genetic adaptations that made dire wolves successful and might identify the factors that contributed to their extinction. Ongoing excavations, particularly in regions outside the well-studied La Brea Tar Pits, may reveal geographical variations within dire wolf populations and how they adapted to different environments across their range. Advanced isotope analysis techniques might further clarify dire wolf diets and migration patterns throughout their evolutionary history. Computational approaches, including artificial intelligence analysis of morphological data across thousands of specimens, could reveal subtle patterns previously undetectable through traditional methods. As climate change reshapes modern ecosystems, the study of dire wolves and other extinct Pleistocene species provides valuable perspectives on how predators respond to environmental shifts, offering lessons potentially applicable to conservation efforts for their modern relatives.

Conclusion: The Dire Wolf’s Legacy

The dire wolf represents a fascinating chapter in North America’s natural history—a highly successful predator that thrived for over 100,000 years before disappearing forever. Far from the mythologized creatures of fantasy, the real dire wolves were remarkable animals in their own right, with specialized adaptations that made them perfect hunters in the Pleistocene ecosystem. Their extinction reminds us of nature’s impermanence and the vulnerability of even the most successful species to environmental change. While we may never see living dire wolves again outside of fiction, their legacy continues through scientific discovery and cultural inspiration. From museum displays of their fossilized remains to their fictional counterparts in literature and television, dire wolves continue to captivate our imagination. As research techniques advance, we can expect our understanding of these magnificent predators to deepen further, ensuring that while Canis dirus may be extinct, they are far from forgotten. The dire wolf’s story—spanning millions of years of evolution, ecological dominance, and ultimate extinction—remains a powerful testament to the complex and ever-changing tapestry of life on Earth.