You’ve probably imagined the age of dinosaurs as a time of thunderous roars and primal silence. Yet the prehistoric world was far from quiet. Recent discoveries have shattered Hollywood’s version of the Mesozoic soundscape, revealing an acoustic environment more complex and fascinating than any film could capture.

Picture yourself transported back millions of years where Triceratops might have heard crickets chirping in the evening, while Mesozoic treetops resonated with sounds you’ve never encountered. The real story begins not with the mighty dinosaurs, but with the tiny insects that dominated Earth’s first terrestrial concert halls. So let’s dive into this forgotten symphony of prehistoric life.

The Pioneer Musicians: Insects Take Center Stage

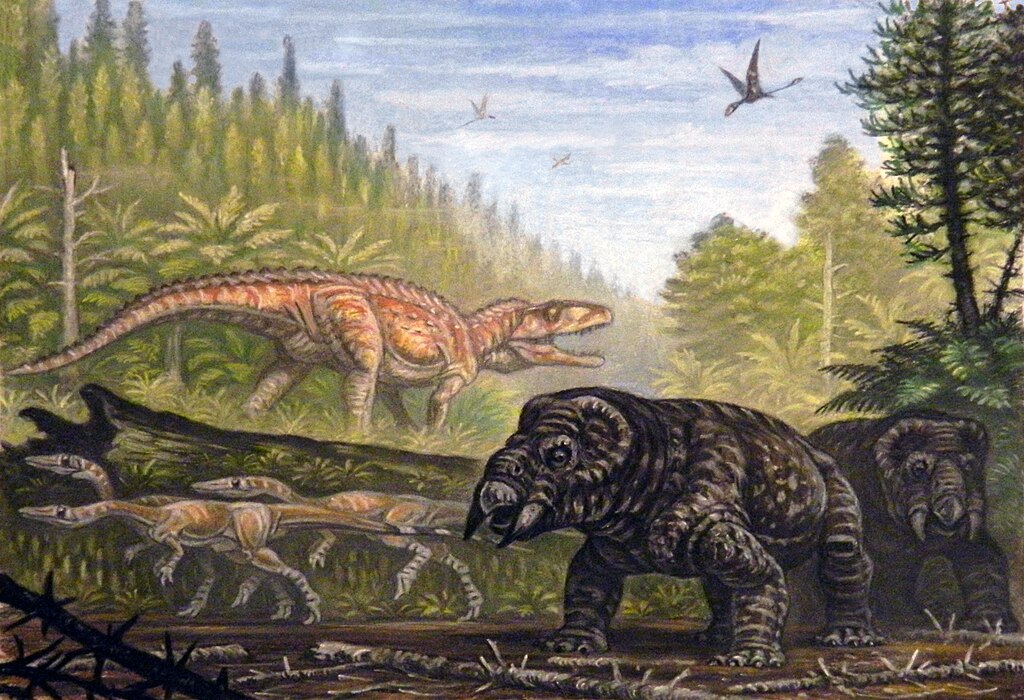

During the Triassic period, stridulating insects, including crickets, performed the first terrestrial twilight choruses. You might find it surprising that these six-legged creatures pioneered acoustic communication on land long before any vertebrate dared to make a sound. Over 100 million years ago, long before the sound of vertebrates such as birds and frogs filled the air, ancient forests were dominated by the chirping of insects.

Think of it this way: while massive reptiles stomped through primeval forests, it was the humble insects that truly understood the power of song. Katydids are the earliest known animals to have evolved complex acoustic communication, acoustic niche partitioning, and high-frequency musical calls. These creatures weren’t just making noise – they were composing the world’s first orchestrated performances.

The Evolution of Sound Through Time

The twilight chorus was joined by water boatmen in the Lower Jurassic, anurans in the Upper Jurassic, geckoes and birds in the Lower Cretaceous, and cicadas and crocodilians in the Upper Cretaceous. You can imagine each geological period adding new instruments to nature’s growing orchestra. The progression wasn’t random – it followed a careful evolutionary timeline that built complexity layer by layer.

During the Triassic, insects especially katydids dominated the choruses, although some reptiles and amphibians may have made sounds. During the Jurassic, when the world became truly noisy, vertebrate animals had evolved a wide range of vocal abilities. Honestly, this gradual crescendo over millions of years makes modern musical evolution seem lightning fast in comparison.

Dinosaurs: The Silent Giants Myth Debunked

Acoustic displays by non-avian dinosaurs were therefore probably non-vocal. This revelation might shatter your Jurassic Park fantasies, yet it opens up an entirely different acoustic world. Theropods might have used low-frequency booms or bellows, akin to modern-day crocodiles, creating sounds through closed-mouth techniques rather than roaring vocals.

Scientists at Sandia National Laboratories collaborated to recreate the sound a dinosaur made 75 million years ago, finding that the dinosaur had a bony tubular crest that extended back from the top of its head, containing a labyrinth of air cavities and shaped something like a trombone. Some sauropods made percussion sounds by cracking their tails in the air like a whip, while dinosaurs made closed-mouth booms and forced-air hisses.

The Sophisticated Cricket Symphony

Researchers discovered tympanal ears dating to 160 million years ago, making them the earliest-known insect ears, while studying 87 fossils from China, South Africa and Kyrgyzstan dating from 150 to 240 million years ago during the Middle Triassic to the Middle Jurassic. These discoveries prove that ancient insects possessed hearing capabilities we’re only beginning to understand.

Reconstructing the sounds produced by katydids revealed they had evolved a high diversity of singing frequencies, including high-frequency calls, by at least the Late Triassic around 200 million years ago. By at least the Middle Jurassic, they had evolved complex acoustic communication, including mating signals, communication between males and directional hearing. The katydid’s high-frequency, short-range musical calls allowed them to communicate over shorter distances above the upper hearing limit of most Mesozoic animals.

When Birds Finally Found Their Voice

A team of palaeontologists confirmed they had discovered the oldest known fossil of a bird’s voice box, known as a syrinx, found in the remains of an extinct Antarctic bird named Vegavis, which died at least 66 million years ago and lived alongside the dinosaurs. The fact that the syrinx was not more widespread at the time suggests that the bird’s voice box arrived relatively late in the evolutionary game.

You might assume birds were among the first to sing, yet they were actually latecomers to the acoustic party. Birds appeared in the Late Jurassic, although their special vocal structure is only reported from the latest Cretaceous. Ancient birds honked and quacked, but the Chicxulub asteroid impact quieted the chorus 66 million years ago, though it didn’t silence it forever.

The Amphibian Chorus Emerges

The first Lissamphibians (modern amphibians) appeared in the Triassic, with the progenitors of the first frogs already present by the Early Triassic. However, the group as a whole did not become common until the Jurassic, when the temnospondyls had become very rare. Before modern frogs took center stage, ancient waterways echoed with completely different sounds.

The waterways were instead filled with a different, distinct group of amphibians known as the Temnospondyls. These were much larger animals, some of which grew up to four metres in length. They physically resembled modern crocodiles and likely filled a similar ecological role. The appearance of the earliest crabs and modern frogs, salamanders and lizards marked major events in the Jurassic.

The Mammalian Whisper Network

By 225 million years ago, one branch gave rise to the mammaliaformes, which were likely small, nocturnal insectivores. Early mammals were likely nocturnal insectivores, keeping out of the way of dominant archosaurs. The bones of early mammals show that their hearing had improved by the Jurassic, likely due to predatory eves-dropping on insects.

These tiny creatures developed remarkable acoustic abilities out of necessity. The Early – Middle Jurassic katydid transition coincided with the diversification of derived mammalian clades and improvement of hearing in early mammals, supporting the hypothesis of the acoustic coevolution of mammals and katydids. Imagine these mouse-sized animals perfecting their hearing to better hunt the very insects that invented terrestrial music.

A World Without Modern Melodies

Most large animals were reptiles rather than mammals; there were no dinosaurs, no bird sounds, and no flowers to pick or grass to mow during the earliest parts of the Mesozoic. The must have been a truly alien sounding symphony. You would have encountered acoustic environments completely unlike anything in today’s world.

With dinosaurs already pushing biology to its extremes in many other aspects, its absolutely possible they were capable of creating sounds that we don’t even have names for. Long-distance acoustic communication brought many advantages for Mesozoic katydids, including locating and assessing rivals or mates from a safe distance under varying light conditions. To be able to take advantage of long-distance acoustic communication, insects need to both encode and extract relevant information like the location and species identity of mates and rivals.

The Mesozoic soundscape wasn’t just background noise – it was a complex, evolving acoustic ecosystem where every chirp, buzz, and boom served a purpose. From the pioneering cricket concerts of the Triassic to the emerging bird songs of the Late Cretaceous, these prehistoric melodies laid the foundation for every sound you hear in nature today. The next time you listen to a cricket’s evening serenade, remember you’re experiencing an acoustic tradition that began when dinosaurs walked the Earth. What other prehistoric secrets do you think modern soundscapes might be hiding?