When we think of saber-toothed predators, our minds typically conjure images of the iconic Smilodon, often called the saber-toothed tiger (though it wasn’t a tiger). However, the story of saber-toothed creatures is far more complex and fascinating than most people realize. Among the most intriguing chapters in this evolutionary tale is that of Thylacosmilus, a remarkable saber-toothed predator that evolved completely independently from cats, on an entirely different branch of the mammalian family tree. This South American marsupial represents one of the most striking examples of convergent evolution in the fossil record, developing similar adaptations to the famous saber-toothed cats despite having no close relationship to them. Let’s explore this extraordinary animal that carried impressive saber teeth but wasn’t remotely feline.

Marsupial Origins: Not Related to Cats at All

Thylacosmilus belonged to a group of mammals called metatherians, which includes modern marsupials like kangaroos, koalas, and opossums. While saber-toothed cats like Smilodon were placental mammals (eutherians) related to modern big cats, Thylacosmilus shared no close evolutionary relationship with them. The last common ancestor between Thylacosmilus and saber-toothed cats existed over 160 million years ago, making their similar appearances all the more remarkable. This marsupial predator evolved in South America during its isolation as an island continent, developing its distinctive features independently through the process of convergent evolution. Like modern marsupials, Thylacosmilus likely gave birth to extremely underdeveloped young that would have completed their development in a pouch, a reproductive strategy completely different from that of cats.

The Age of Thylacosmilus: Ruling Ancient South America

Thylacosmilus lived during the Late Miocene to Pliocene epochs, approximately 9 to 3 million years ago, in what is now South America. During this time, South America was an isolated continent, having separated from Antarctica millions of years earlier, creating a unique evolutionary laboratory. This isolation allowed distinctive mammals to evolve, including many marsupial species that filled ecological niches occupied by placental mammals elsewhere. Thylacosmilus emerged as one of the apex predators in this isolated ecosystem, hunting the diverse megafauna that roamed the ancient South American grasslands and woodlands. Interestingly, its reign came to an end around the time of the Great American Interchange, when North and South America connected via the Panama land bridge, allowing northern predators like true saber-toothed cats to enter South America and potentially outcompete the native marsupial predators.

Impressive Canines: Longer Than Those of Smilodon

Perhaps the most striking feature of Thylacosmilus was its enormous, curved upper canine teeth, which were proportionally even longer than those of the famous Smilodon. These impressive sabers could reach up to 7 inches in length, extending well below the lower jaw when the mouth was closed. Unlike those of saber-toothed cats, the canines of Thylacosmilus continued to grow throughout the animal’s life, more like the incisors of rodents than typical mammalian canines. This continuous growth required special adaptations to prevent damage and breakage. The teeth were protected by a bony flange that extended downward from the lower jaw, creating a sheath-like structure that helped guard the sabers when the mouth was closed. This unique dental arrangement represents a fascinating case of parallel evolution, achieving a similar hunting adaptation through a completely different developmental pathway.

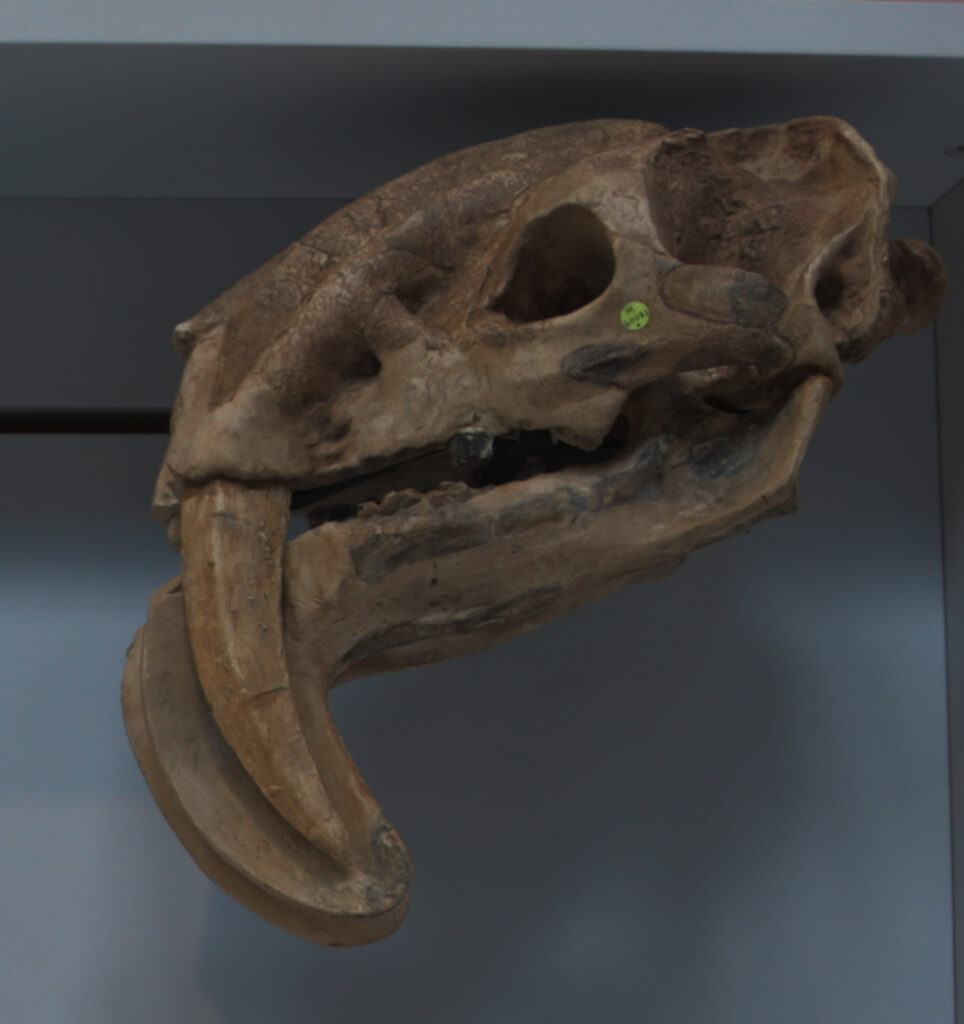

Skull Adaptations: Built for Stabbing Power

The skull of Thylacosmilus featured remarkable specializations that supported its saber-toothed lifestyle. The cranium showed extensive reinforcement to anchor powerful neck muscles, which would have been crucial for the stabbing motion used to deploy its impressive canines effectively. The zygomatic arches (cheekbones) were exceptionally robust, indicating attachment points for massive jaw muscles that could generate tremendous force. Unlike most carnivorous mammals, Thylacosmilus had a relatively weak bite force at its molars, suggesting it didn’t rely on crushing bones like modern big cats do. Instead, its entire skull was optimized for a specialized killing technique involving the canines. The nasal opening was positioned unusually high on the skull, possibly allowing the animal to breathe while its mouth and canines were embedded in prey—an adaptation that highlights how specialized this marsupial had become for its predatory lifestyle.

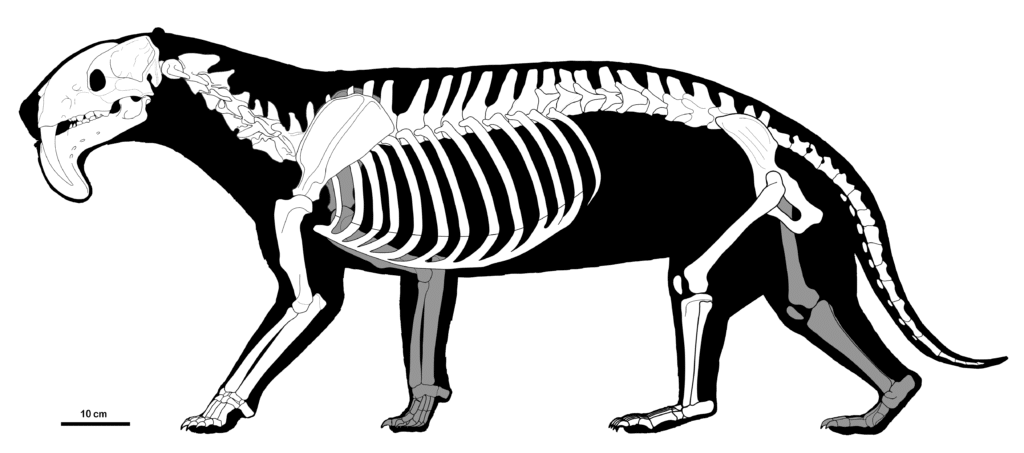

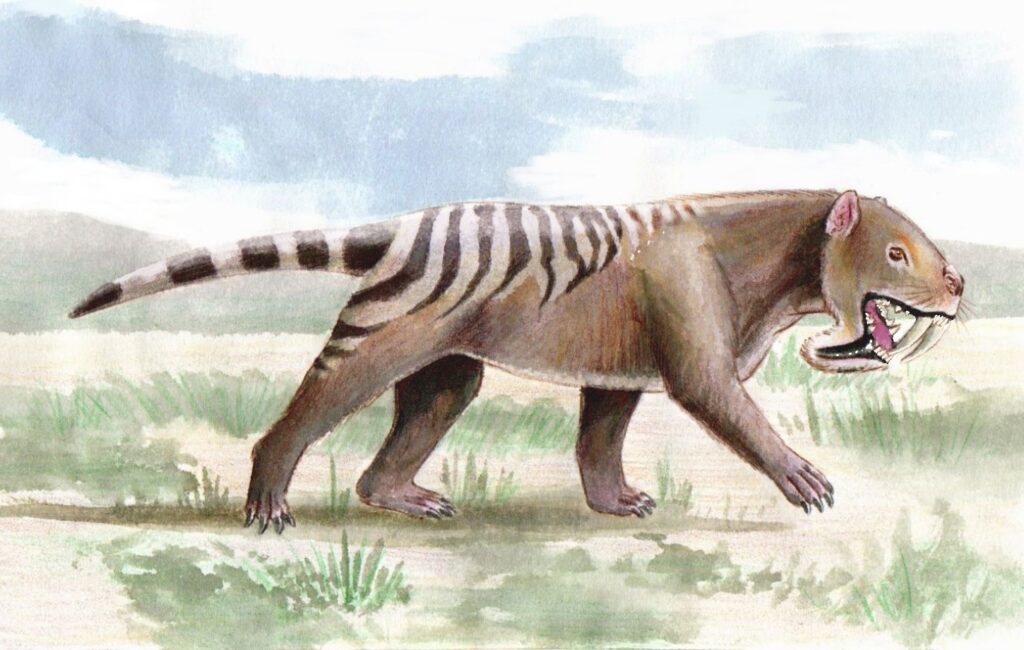

Body Structure: A Different Kind of Predator

Thylacosmilus possessed a body structure noticeably different from that of saber-toothed cats, reflecting its separate evolutionary history. Weighing approximately 330-440 pounds (150-200 kg), it was roughly the size of a jaguar but built quite differently. Its forelegs were powerful but didn’t show the extreme adaptations for grappling with prey seen in Smilodon. The marsupial predator had a somewhat plantigrade stance (walking partially on the soles of its feet) rather than the digitigrade posture (walking on toes) typical of cats, suggesting it was less adapted for rapid pursuit. Its robust build indicates considerable strength, likely used to overcome and subdue large prey once caught. The overall body proportions suggest Thylacosmilus was an ambush predator that relied on surprise attacks rather than speed and pursuit, convergent with but distinct from the hunting strategy of saber-toothed cats.

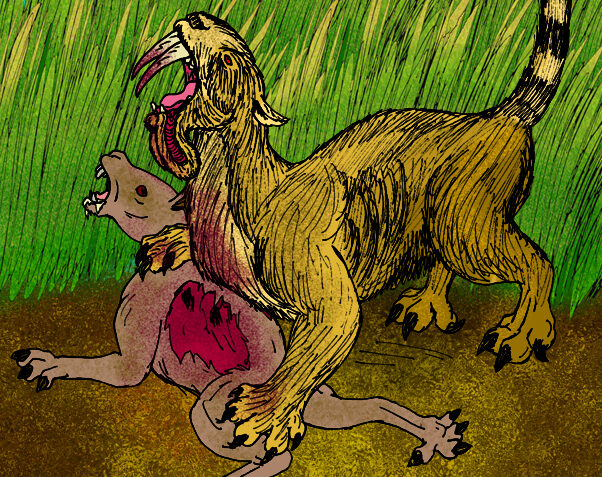

Hunting Techniques: How They Used Those Impressive Teeth

Paleontologists have extensively debated how Thylacosmilus employed its massive canines to dispatch prey. The current consensus suggests it used a precisely targeted stabbing motion, driving its sabers into vital areas of prey animals to cause rapid blood loss. This hunting method would have required remarkable precision and control, as the fragile canines could easily break if they contacted bone. Unlike modern big cats that typically kill with a suffocating bite to the throat, Thylacosmilus likely used its powerful forelimbs to restrain prey while positioning for the fatal strike with its sabers. This specialized killing technique may have been particularly effective against the large, thick-skinned herbivores that inhabited South America during this period. Recent biomechanical studies indicate that Thylacosmilus had especially strong neck muscles, which would have been crucial for withdrawing its deeply embedded canines from prey without damaging them—a critical capability for an animal whose hunting strategy centered entirely on these specialized teeth.

Convergent Evolution: Nature’s Repeated Experiment

Thylacosmilus represents one of the most striking examples of convergent evolution in the fossil record—the phenomenon where unrelated organisms independently evolve similar traits in response to similar environmental pressures. Despite sharing no close ancestry with feline predators, Thylacosmilus evolved a remarkably similar saber-toothed adaptation for hunting large prey. This evolutionary parallel occurred at least three times among mammals: in the true saber-toothed cats (machairodontines like Smilodon), in the marsupial Thylacosmilus, and in the nimravids (another group of carnivores sometimes called “false saber-toothed cats”). Such repeated evolution of similar adaptations strongly suggests that the saber-toothed predatory strategy was highly effective in certain ecological contexts, particularly for hunting large herbivores. These natural experiments in evolution demonstrate how specific environmental challenges can drive drastically different animal lineages toward similar solutions, despite their distinct evolutionary histories and different developmental pathways.

Reproduction: Marsupial Motherhood

As a marsupial, Thylacosmilus would have had a reproductive strategy fundamentally different from that of placental mammals like saber-toothed cats. Modern marsupials give birth to extremely underdeveloped young after a very short gestation period, with most development occurring while the offspring are attached to teats, often within a protective pouch. Thylacosmilus females likely had a similar reproductive pattern, giving birth to tiny, embryonic young that would crawl to a pouch where they would continue developing. This reproductive strategy represents a major physiological difference between Thylacosmilus and superficially similar placental predators like Smilodon. The marsupial approach to reproduction would have influenced many aspects of Thylacosmilus’s life history and behavior, potentially including social structure, parental investment, and population dynamics. Paleontologists can only speculate about these aspects, but the fundamental differences in reproduction underscore how distinct this animal was from the saber-toothed cats despite their convergent hunting adaptations.

Ecological Role: South America’s Top Predator

During its existence, Thylacosmilus occupied the position of apex predator in the South American ecosystem, playing a crucial role in controlling herbivore populations and influencing their behavior and evolution. The ancient South American landscape featured a diverse array of potential prey animals, including large native ungulates, ground sloths, and early relatives of armadillos and anteaters. As the dominant predator, Thylacosmilus would have exerted significant selective pressure on these herbivore species, potentially driving the evolution of defensive adaptations. The predator-prey relationships involving Thylacosmilus would have been fundamental to the functioning of this isolated ecosystem, shaping energy flows and population dynamics across the food web. Its specialized hunting strategy likely allowed it to target prey that other predators couldn’t effectively handle, creating a unique ecological niche that lasted for millions of years until continental connections brought competition from northern predators.

Discovery and Naming: Scientific History

Thylacosmilus was first discovered in the 1920s in Argentina by paleontologists working in fossil-rich Pliocene deposits. The genus name Thylacosmilus combines the Greek words “thylakos” (pouch) and “smilos” (knife or saber), literally meaning “pouch knife,” referencing both its marsupial nature and its distinctive canine teeth. The most complete fossils belong to the species Thylacosmilus atrox, with “atrox” meaning “terrible” or “frightening” in Latin. The initial discovery caused considerable scientific excitement, as it represented a dramatic example of convergent evolution that had not previously been documented. Early interpretations sometimes overemphasized the similarities to saber-toothed cats, but more detailed anatomical studies revealed the fundamental differences between these superficially similar predators. The discovery of Thylacosmilus significantly expanded scientific understanding of marsupial diversity and demonstrated the remarkable adaptive potential of this mammalian lineage.

Extinction: The End of an Evolutionary Experiment

Thylacosmilus disappeared from the fossil record approximately 3 million years ago, coinciding with significant ecological changes in South America. This extinction appears to correlate with the Great American Interchange, when the formation of the Panama land bridge connected North and South America, allowing northern animals to migrate southward and vice versa. Among the northern immigrants were true cats, including early saber-toothed cats like Smilodon, which may have outcompeted Thylacosmilus for prey resources. Some paleontologists suggest that the placental predators had advantages in terms of intelligence, reproductive strategy, or metabolic efficiency that allowed them to displace the marsupial predator. Other factors potentially contributing to its extinction include climate change and alterations in prey species composition. The extinction of Thylacosmilus represents the end of a fascinating evolutionary experiment—a specialized marsupial predator that had evolved in isolation but ultimately could not compete when confronted with ecological change and new competitors.

Recent Research: New Insights into an Ancient Predator

Recent scientific analyses have provided new perspectives on how Thylacosmilus lived and hunted, sometimes challenging long-held assumptions. Advanced biomechanical studies using computer modeling have suggested that, despite appearances, Thylacosmilus may have employed its saber teeth differently than Smilodon did. Some research indicates that its bite was even weaker than previously thought, emphasizing the importance of neck muscles rather than jaw strength in its killing technique. Comparative studies of tooth wear patterns between Thylacosmilus and saber-toothed cats have revealed subtle differences that might reflect variations in prey preference or killing methods. Isotope analyses of fossilized teeth have provided clues about the marsupial predator’s diet, suggesting it specialized in certain prey types within its ecosystem. These ongoing research efforts continue to refine our understanding of this remarkable predator, highlighting both the similarities and differences between Thylacosmilus and the more familiar saber-toothed cats, and emphasizing the importance of examining convergent evolution with nuanced scientific approaches.

Cultural Impact: Beyond Scientific Significance

Though less well-known to the general public than Smilodon, Thylacosmilus has nevertheless made its mark on our cultural understanding of prehistoric life. The discovery of this marsupial saber-tooth dramatically expanded scientific and public appreciation for the diversity of extinct predators and the complexity of evolutionary processes. Thylacosmilus has been featured in numerous paleontological exhibitions worldwide, where it often serves to illustrate the concept of convergent evolution and the diversity of prehistoric South American fauna. It has appeared in documentary series about prehistoric life, including specialized programs focusing on ancient South America or the evolution of mammals. For educators, Thylacosmilus provides a compelling example for teaching evolutionary concepts, as its parallel development of saber teeth makes the abstract idea of convergent evolution concrete and understandable. The continuing fascination with this animal reflects humanity’s enduring interest in remarkable predators and the surprising pathways that evolution can take in different parts of the world.

Conclusion

Thylacosmilus stands as one of the most fascinating examples of convergent evolution in the fossil record. This marsupial predator, despite having no close relationship to cats, developed remarkably similar adaptations for a specialized predatory lifestyle, including its iconic saber teeth. Its existence in isolation in ancient South America created a unique evolutionary experiment that lasted millions of years before changing conditions led to its extinction. The story of Thylacosmilus reminds us that evolution can produce strikingly similar solutions to ecological challenges in completely unrelated animal lineages, while still reflecting the distinctive characteristics of each evolutionary branch. As scientific research continues to uncover new details about this remarkable animal, we gain deeper insights not only into this specific predator but also into the broader patterns and processes that shape life’s diversity across time and space.