Paleontologists are scientific detectives, uncovering the mysteries of prehistoric life that walked our planet millions of years ago. When these fossil hunters head into the field to excavate dinosaur remains, they don’t just grab a shovel and bucket. Modern paleontological expeditions require careful planning and a specialized toolkit that combines traditional tools with cutting-edge technology. From the rugged badlands of Montana to the remote deserts of Mongolia, these scientists arrive prepared with equipment designed to locate, extract, protect, and document ancient remains. This article explores the essential tools that paleontologists pack when embarking on dinosaur excavations, offering a glimpse into the meticulous work that brings prehistoric giants back into our modern understanding.

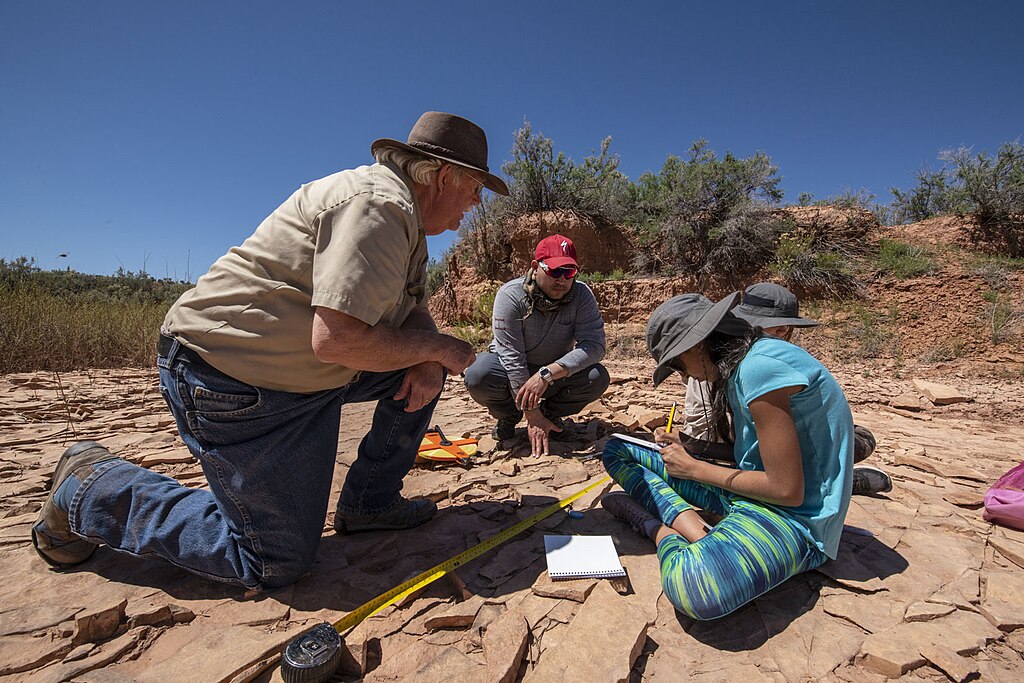

Mapping and Navigation Equipment

Before the first fossil is unearthed, paleontologists must know precisely where they’re going and document exactly where specimens are found. Modern GPS units have revolutionized field mapping, allowing researchers to mark fossil locations with pinpoint accuracy and return to productive sites year after year. Many teams also bring traditional topographic maps and compasses as reliable backups in remote areas where electronic devices might fail. Satellite phones provide essential communication capabilities in locations far from cellular coverage. Digital mapping software loaded onto rugged field tablets allows teams to create detailed site maps, recording the position of each bone in relation to others and the surrounding geological features. These precise spatial records are crucial for later research, helping scientists understand how dinosaur remains became preserved and potentially revealing information about ancient environments and death assemblages.

Geological Survey Tools

Understanding the geological context of fossil discoveries is fundamental to paleontological work, making geological survey tools essential components of any dig kit. Rock hammers with chiseled ends allow scientists to break samples for examination and test the hardness of different rock layers. Pocket magnifiers help examine sedimentary details that might reveal the age and depositional environment of fossil-bearing rocks. Field notebooks with waterproof pages provide space to record detailed observations about rock types, layering patterns, and sedimentary structures. Many paleontologists also carry acid bottles containing dilute hydrochloric acid, which reacts with carbonate minerals and helps identify limestone layers. Clinometers measure the angle of rock beds, providing crucial information about the tectonic history of fossil sites and how layers may have shifted since deposition. Together, these tools help scientists read the “rock record” surrounding their fossil finds, placing dinosaur discoveries within their proper geological and temporal context.

Excavation Tools: From Basic to Specialized

The bread and butter of any paleontological expedition consists of tools designed to carefully remove rock from around fossilized bones. Standard shovels and picks help with initial overburden removal, clearing away layers of soil and rock above fossil-bearing horizons. As work approaches actual fossil material, the tools become progressively more delicate. Awls, dental picks, and fine brushes allow for precision work around fragile specimens, gradually exposing bones without causing damage. Air scribes—essentially miniature pneumatic jackhammers powered by compressors—have revolutionized fossil preparation, allowing paleontologists to remove matrix (surrounding rock) with greater speed and control than hand tools alone. For the finest detail work around extremely delicate specimens, some paleontologists employ modified needles mounted in pencil-like holders. Power equipment, including gas-powered rock saws, may be used for cutting through particularly tough matrix, though these are employed cautiously and typically at a distance from actual fossil material. The selection of tools varies depending on the hardness of the surrounding rock and the fragility of the fossils being excavated.

Documentation Equipment

Comprehensive documentation is a cornerstone of scientific fossil collection, requiring specialized equipment to record discoveries accurately. Digital cameras with macro lenses capture detailed images of fossils both in situ (in their original position) and during various stages of excavation. These photographic records provide valuable reference material for later laboratory work and publication. Portable light setups, including LED panels with diffusers, ensure consistent, shadow-free documentation even in challenging field conditions. Scale bars and color charts are included in photographs to provide accurate size references and true color representation. Many modern expeditions also incorporate photogrammetry—taking multiple overlapping photographs that specialized software can later convert into detailed 3D models of fossils and dig sites. Video equipment records the excavation process, capturing techniques and contextual information that might otherwise be lost. Some teams even employ drones to capture aerial imagery of larger sites, providing valuable perspective on the broader geological context and spatial relationships between different fossil discoveries.

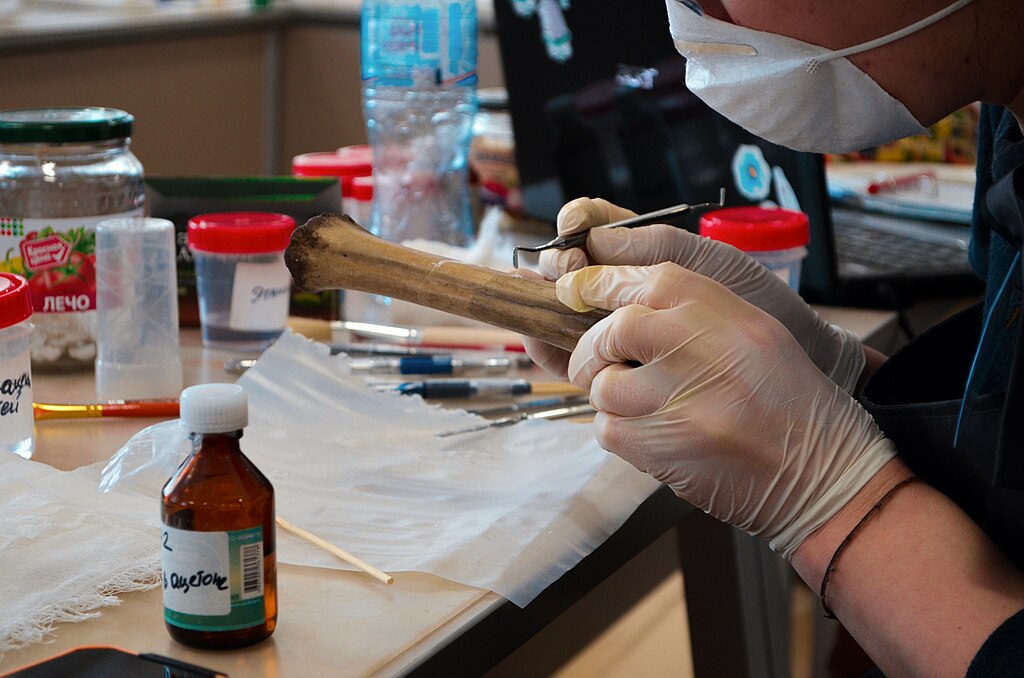

Preservation and Stabilization Materials

Fossil bones are often extremely fragile when first exposed, requiring immediate stabilization to prevent damage during excavation and transport. Consolidants such as Paraloid B-72, an acrylic resin dissolved in acetone, are applied to strengthen fragile fossils by penetrating the porous bone and hardening to provide structural integrity. These consolidants are carried in squeeze bottles for precise application in the field. For extremely delicate specimens, cyanoacrylate adhesives (similar to super glue) provide immediate stabilization of small cracks and fragmented areas. Paleontologists also pack rolls of toilet paper, paper towels, and acid-free tissue for cushioning delicate specimens. Aluminum foil creates protective wrappings that conform to irregular fossil shapes while providing some rigidity. For larger specimens, burlap strips dipped in plaster of Paris create protective field jackets—hardened shells that encase and protect fossils during transport back to the laboratory. These materials, though seemingly simple, represent the critical first line of defense in preserving specimens that have survived millions of years only to face their most vulnerable moment upon exposure to modern elements.

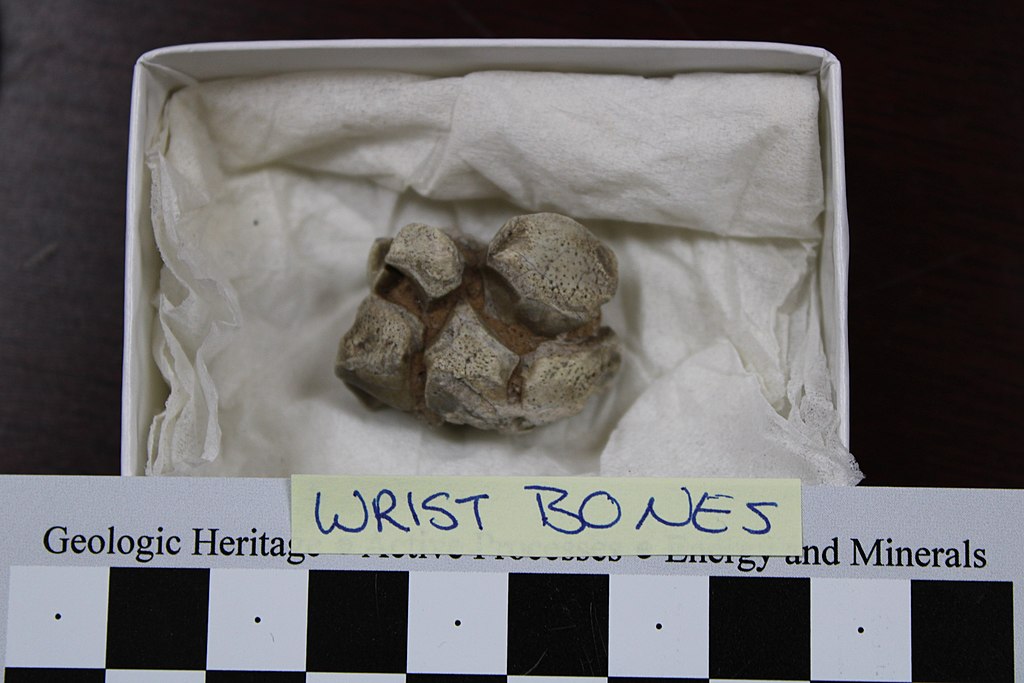

Collection and Storage Solutions

Proper collection and organization of fossil specimens require specialized containers and labeling systems. Small fossil fragments are typically placed in plastic zip-top bags with detailed labels written on acid-free paper using archival ink that won’t fade over time. These bags are often organized in plastic containers with dividers to prevent shifting during transport. For slightly larger specimens, paleontologists pack sturdy plastic boxes lined with protective foam or bubble wrap to prevent movement and potential damage. Field labels accompany every specimen, recording crucial information including the exact location (with GPS coordinates), date of collection, collector’s name, and preliminary identification if possible. Specimen numbers are assigned in the field following established cataloging systems unique to each institution. Many teams now use handheld label printers that create durable, waterproof tags that won’t degrade in field conditions. Environmental data loggers may be included with particularly sensitive specimens to record temperature and humidity fluctuations during transport, ensuring that any potential damage can be documented and addressed.

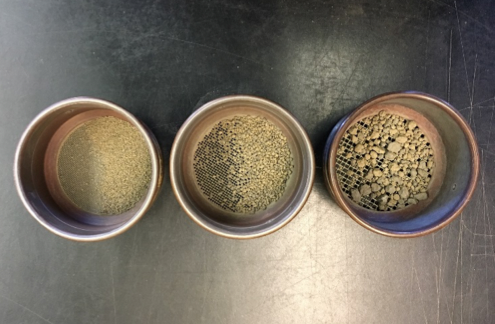

Prospecting Equipment

Before excavation can begin, paleontologists must first locate promising fossil sites through a process called prospecting. Experienced fossil hunters develop a trained eye for spotting bone fragments eroding from hillsides, but they also rely on specific tools to aid their search. Field glasses and binoculars allow examination of distant outcrops that might show telltale signs of fossil material. Walking sticks serve dual purposes—providing stability on uneven terrain while also probing suspicious objects without having to bend down repeatedly. Some teams employ small garden rakes to gently search through surface sediments. In certain geological contexts, paleontologists use screens of various mesh sizes to sift sediment for microfossils and small bone fragments that might indicate larger specimens nearby. Modern prospecting may also incorporate drone surveys with high-resolution cameras to identify promising areas from above, particularly useful in large, open terrain. These prospecting tools help maximize efficiency in the field, allowing teams to identify the most promising sites before committing to full-scale excavation.

Personal Field Gear

Paleontological fieldwork often takes place in remote, rugged environments with extreme weather conditions, necessitating appropriate personal equipment. Wide-brimmed hats and high-SPF sunscreen protect against intense sun exposure during long days in open terrain. Sturdy hiking boots with ankle support are essential when traversing uneven ground and provide protection from sharp rocks and potentially dangerous wildlife. Work gloves prevent blisters during digging while also offering protection when handling rough rock surfaces and sharp tools. Many paleontologists wear knee pads or carry portable foam kneeling pads for comfort during extended periods of detailed excavation work. Bandanas serve multiple purposes—from sun protection to dust filtering during windy conditions. Field clothes typically feature multiple pockets for carrying small tools and specimens, with lightweight, quick-drying fabrics preferred for comfort in variable conditions. Personal hydration systems, including large-capacity water bottles or backpack-style reservoirs, are critical when working in hot, arid environments where dehydration poses a serious health risk.

Laboratory Preview Tools

Some preliminary laboratory work often takes place in field camps, requiring portable versions of lab equipment. Portable microscopes, including digital USB microscopes that connect to laptops, allow for detailed examination of smaller specimens directly in the field. Ultraviolet lights reveal details in some fossils that aren’t visible under normal lighting conditions, potentially highlighting organic residues or different mineral compositions. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzers, though expensive, are increasingly common on major expeditions, allowing preliminary elemental analysis of fossils and surrounding rock without destructive sampling. Small digital scales provide precise weight measurements for specimens, useful for documentation and transportation planning. Temporary preparation stations might include small air compressors powering pneumatic tools for initial fossil cleaning when time constraints or fragility make it necessary to begin preparation before returning to the main laboratory. These field-based laboratory tools provide immediate scientific insights and help teams make informed decisions about which specimens warrant priority attention and special handling procedures during transport.

Digital Field Technology

Modern paleontological expeditions increasingly rely on digital technologies that streamline documentation and enhance scientific analysis. Ruggedized tablet computers loaded with specialized software allow immediate digital data entry, eliminating potential errors from transcribing field notes later. Digital calipers connected to these devices can automatically record measurements directly into databases. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) scanning technology creates detailed three-dimensional models of excavation sites and individual specimens with millimeter precision. Some teams employ ground-penetrating radar to identify potential fossil deposits before excavation begins, allowing more targeted and efficient digging. Portable battery systems, including solar chargers and power banks, maintain these electronic tools in remote locations lacking conventional power sources. Specialized database applications help manage the complex relationships between specimens, photographs, measurements, and geological data collected in the field. While these technologies represent significant investments, they dramatically improve the quality and quantity of scientific data recovered from paleontological expeditions.

Camp and Survival Equipment

Extended paleontological expeditions in remote areas require substantial camping and survival gear to support research teams. Durable, weather-resistant tents provide shelter, with larger expedition-grade models often serving as field laboratories and common areas. Portable cooking equipment, including camp stoves and fuel, allows teams to prepare meals in locations far from restaurants or other food services. Water purification systems, including filters and chemical treatments, ensure safe drinking water when natural sources must be utilized. First aid kits are customized for the specific hazards of each location, from snake bite treatments in desert regions to altitude sickness medications in mountainous areas. Communication equipment, including satellite phones or emergency beacons, provides crucial safety connections in remote regions. Many expeditions include portable generators to power essential equipment and charge batteries for scientific instruments. Vehicle recovery equipment is essential when traveling off-road to remote fossil sites, including winches, traction mats, and spare parts for field repairs. This support equipment, while not directly involved in fossil recovery, creates the foundation that makes extended scientific fieldwork possible in challenging environments.

Specialized Transport Equipment

Moving delicate fossil specimens from remote field locations to research institutions requires customized transportation solutions. Custom-built fossil cradles lined with foam conform to the shape of plaster-jacketed specimens, preventing movement during transport over rough terrain. For particularly large specimens, teams may construct wooden crates reinforced with metal strapping to provide protection during long-distance shipping. Shock indicators attached to containers record potentially damaging impacts during transit. Temperature-controlled containers protect specimens that might be vulnerable to extreme heat or cold during transport. When excavating in extremely remote locations, specialized equipment might include helicopter slings for airlifting large specimens to accessible roads. Some major expeditions employ portable gantry systems—lightweight aluminum frames with chain hoists—to lift heavy jacketed fossils onto transport vehicles. In particularly sensitive cases, vibration-dampening materials isolate specimens from the jarring movements of vehicles traveling across uneven terrain. These transportation solutions represent the final critical step in bringing fossils from the field to the laboratory, where the detailed scientific work of preparation and analysis can begin.

Educational and Public Outreach Materials

Modern paleontological expeditions increasingly incorporate public education components, requiring specific tools for outreach. Digital tablets loaded with animations and reconstructions help field paleontologists explain their work to visitors, local community members, and collaborating scientists. Scaled models of the dinosaurs being excavated provide immediate visual references that help contextualize fragmentary fossil remains. Simplified field guides with basic anatomical terminology assist in explaining discoveries to non-specialists who may visit active dig sites. Many expeditions now include portable video equipment specifically for creating documentary content and social media updates, sharing the excitement of discoveries with worldwide audiences in near-real time. Laminated photographs of previous discoveries from the region help illustrate what complete specimens might look like when only partial remains are currently visible. Some teams prepare multilingual information cards when working internationally, facilitating communication with local communities about the scientific and cultural significance of paleontological work in their region. These educational tools reflect paleontology’s dual mission of scientific discovery and public engagement, recognizing that fossil finds belong to our shared natural heritage.

Paleontological fieldwork represents a fascinating blend of traditional techniques and cutting-edge technology, all aimed at carefully recovering and preserving Earth’s prehistoric past. The tools paleontologists pack for dinosaur digs reflect both the physically demanding nature of the work and the scientific precision required to maximize the information gleaned from each specimen. From the moment a fossil is first spotted eroding from a hillside to its final placement in a museum collection, these specialized tools facilitate the transformation of ancient bones into scientific knowledge. As technology advances, the paleontologist’s toolkit continues to evolve, but the fundamental approach remains unchanged: careful excavation, meticulous documentation, and thorough analysis. These tools, in the hands of skilled scientists, continue to reveal new chapters in the extraordinary story of dinosaurs and the ancient world they inhabited.