In the grand theater of evolution, few performers have shown the staying power of turtles. These remarkable reptiles have survived for over 220 million years, witnessing the rise and fall of dinosaurs and enduring multiple mass extinction events that wiped out countless other species. Their distinctive shells, deliberate pace, and remarkable adaptability have allowed them to persist across eons while maintaining a design that has remained fundamentally unchanged. Today, as human activities threaten biodiversity worldwide, understanding how turtles have managed their extraordinary evolutionary marathon offers valuable insights into resilience and survival in an ever-changing world.

The Evolutionary Marvel of Turtle Origins

Turtles first appeared during the Late Triassic period, approximately 220-230 million years ago, making them one of Earth’s most ancient reptile lineages still in existence. The earliest known turtle ancestor, Odontochelys semitestacea, possessed only a partial shell covering its underside, while Proganochelys, appearing slightly later, featured a more complete shell resembling modern turtles. What makes turtles particularly fascinating to evolutionary biologists is their unusual body plan — no other vertebrate has evolved to encase its shoulder blades and ribs inside a protective bony box. This radical anatomical innovation represented not merely an incremental change but a complete architectural overhaul that proved remarkably successful, allowing turtles to outlive countless other reptilian experiments.

The Protective Masterpiece: Anatomy of the Shell

The turtle’s shell represents one of nature’s most effective defensive structures, evolving over millions of years into a protective fortress. Unlike common misconception, turtles cannot “leave” their shells because these structures are actually part of their skeleton, formed by the fusion of more than 50 bones, including the ribcage and spine. The shell consists of two main sections: the carapace (upper portion) and the plastron (lower portion), connected at the sides by bridges. This remarkable adaptation provides protection from predators while still allowing sufficient flexibility for movement, feeding, and reproduction. The shell’s design varies significantly across species, from the fully enclosed box turtle that can completely retract its limbs, head, and tail, to the flattened, streamlined shell of sea turtles optimized for oceanic navigation.

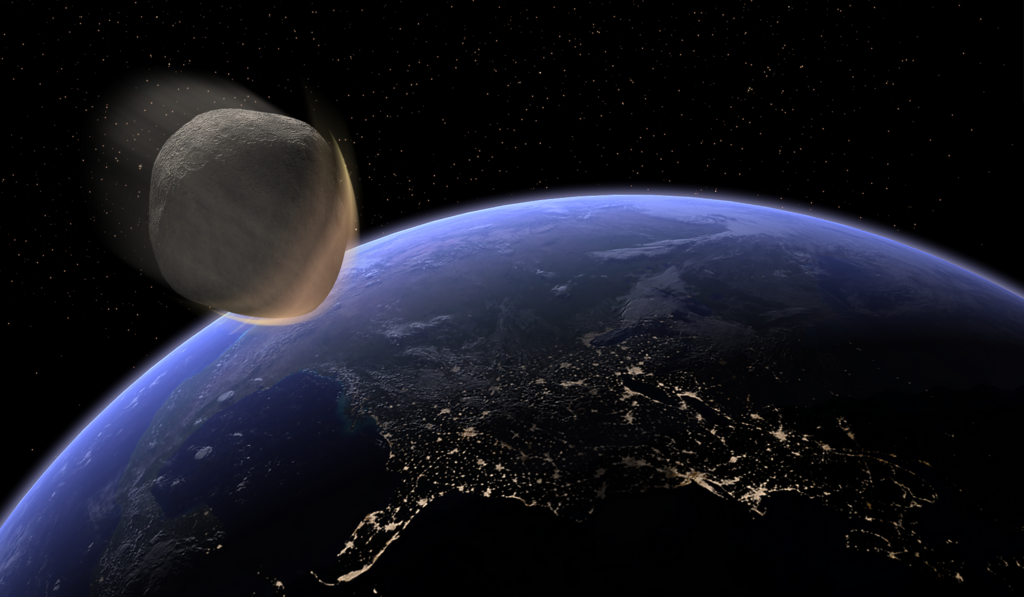

Surviving the K-Pg Extinction Event

When the infamous Chicxulub asteroid struck Earth approximately 66 million years ago, it triggered the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event that eliminated roughly 75% of all species, including all non-avian dinosaurs. Turtles, however, emerged from this catastrophe relatively unscathed. Their survival likely stemmed from several key adaptations: their ability to hold their breath for extended periods, their omnivorous or herbivorous diets allowing flexibility during food scarcity, and their capacity to remain dormant for long periods. Perhaps most crucially, many turtle species could burrow into mud and sediment, potentially shielding them from the immediate aftermath of the impact. This remarkable endurance through one of Earth’s most devastating extinction events demonstrates the effectiveness of the turtle’s evolutionary strategy.

Metabolic Efficiency: The Slow Lane Advantage

Turtles have mastered the art of metabolic efficiency, turning their seemingly slow pace into a survival advantage. As ectotherms (cold-blooded animals), turtles require significantly less energy than similarly sized mammals or birds, allowing them to survive on minimal resources during harsh conditions. Some freshwater turtles can even switch to anaerobic respiration when oxygen is scarce, extracting energy without breathing for months during winter hibernation. The Blanding’s turtle exemplifies metabolic resilience, with documented cases of individuals surviving frozen in ice for weeks. This efficiency extends to their longevity—many species regularly live 50-100 years, with some documented cases exceeding 150 years, giving individual turtles extraordinary temporal resilience against changing environments and temporary threats.

Habitat Versatility Across Millennia

Turtles have demonstrated remarkable adaptability by colonizing nearly every type of habitat available on Earth except the polar extremes. From the open oceans navigated by leatherback sea turtles to the scorching deserts inhabited by tortoises, from freshwater rivers and lakes to tropical rainforests, turtles have evolved specialized adaptations for vastly different environments. The pig-nosed turtle showcases this versatility with its unique combination of flippers for swimming and legs for walking, allowing it to thrive in both aquatic and terrestrial settings. This habitat flexibility has proven crucial during periods of dramatic climate change throughout Earth’s history, as turtles could shift their ranges or adapt to new conditions rather than face extinction when their original environments transformed.

Reproductive Strategies That Withstand Time

The reproductive biology of turtles represents another key to their evolutionary success. Most turtle species produce large numbers of eggs, creating a statistical advantage for survival even if many offspring perish. Sea turtles epitomize this approach, with females laying clutches of 100 or more eggs several times during a nesting season. Additionally, many species exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination, where the incubation temperature determines whether hatchlings develop as males or females. This mechanism, while creating vulnerability to climate change, has historically provided population flexibility in response to environmental shifts. Perhaps most remarkably, some turtles like the painted turtle possess the ability to delay egg development through embryonic diapause if conditions aren’t favorable, effectively hedging their reproductive bets across multiple seasons.

Dietary Flexibility Through Changing Ecosystems

Throughout their 220-million-year history, turtles have encountered dramatic shifts in available food sources as ecosystems transformed around them. Their success partly stems from wide-ranging dietary adaptability, with different species evolving as specialists and generalists. The alligator snapping turtle exemplifies specialized feeding with its worm-like tongue lure that attracts fish directly into its powerful jaws. Conversely, red-eared sliders demonstrate exceptional dietary flexibility, readily consuming plants, insects, fish, carrion, and almost anything edible—allowing them to exploit whatever food becomes available. This nutritional versatility proved particularly valuable during extinction events when food webs collapsed and dietary specialists often perished. Many turtle species can also survive extended fasting periods, with desert tortoises capable of going up to a year without food when necessary.

Behavioral Adaptations for Long-term Survival

Beyond physical traits, turtles have developed sophisticated behavioral adaptations that enhance their survival prospects. Many freshwater species practice brumation, a hibernation-like state where they burrow into mud during winter months, drastically reducing their metabolic needs while waiting for favorable conditions to return. Conversely, desert tortoises estivate during extreme heat, retreating to burrows and becoming dormant until temperatures moderate. Maternal behavior also supports species survival, with female turtles often traveling remarkable distances to find ideal nesting locations—loggerhead sea turtles may migrate hundreds or thousands of miles between feeding and nesting grounds. Perhaps most impressive is the navigation ability of sea turtles, which can detect Earth’s magnetic field to locate specific beaches where they themselves hatched decades earlier, maintaining crucial nesting site fidelity across generations.

Modern Threats: The Anthropocene Challenge

Despite surviving multiple natural extinction events, turtles now face unprecedented challenges from human activities. Habitat destruction removes critical nesting areas and fragments populations, while pollution—particularly plastics in marine environments—causes significant mortality. Climate change threatens to disrupt temperature-dependent sex determination, potentially creating populations with severely skewed gender ratios. The illegal pet trade and harvesting for traditional medicines have decimated numerous populations, particularly in Asia where several species now teeter on extinction’s edge. Road mortality claims countless individuals annually as turtles, particularly females seeking nesting sites, attempt to cross highways. These modern threats operate at speeds and scales that outpace turtles’ evolutionary responses, creating a crisis for creatures that previously weathered every natural catastrophe Earth has experienced since the Triassic period.

Conservation Success Stories: Humanity as Ally

Despite the grim outlook for many turtle species, conservation efforts have demonstrated that decline isn’t inevitable. The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, once down to fewer than 300 nesting females in the 1980s, has seen numbers increase tenfold through protected nesting beaches, fishing regulation changes, and international cooperation between Mexico and the United States. Similarly, the Española giant tortoise of the Galápagos Islands rebounded from just 14 individuals to over 2,000 today through a carefully managed captive breeding program. Conservation techniques have become increasingly sophisticated, including headstarting programs where eggs and hatchlings are protected during their most vulnerable life stages, artificial incubation to ensure balanced sex ratios, and habitat restoration projects. These successes provide templates for broader turtle conservation and demonstrate that human intervention can reverse even severe population declines.

Genetic Resilience and Evolutionary Potential

The genetic makeup of turtles contributes significantly to their evolutionary endurance. Recent genomic research has revealed that many turtle species maintain surprisingly high genetic diversity despite small population sizes, providing raw material for adaptation to changing conditions. The western painted turtle genome, for example, contains unique adaptations for oxygen deprivation tolerance and cold resistance that allow survival through harsh winters. Some turtle lineages demonstrate remarkable evolutionary rate heterogeneity, with periods of rapid adaptation punctuating longer stretches of stability. Particularly fascinating is evidence that certain turtle species can hybridize when populations become isolated or fragmented, potentially creating new genetic combinations that might enhance survival prospects. Researchers are now working to understand how these genetic mechanisms might help turtles respond to anthropogenic challenges, though the pace of modern environmental change may outstrip even these impressive adaptive capabilities.

The Future of Turtles in a Human-Dominated World

The fate of turtles now rests largely in human hands as we determine how to balance development with conservation. Strategic initiatives focusing on critical habitat protection, particularly nesting beaches and migration corridors, offer the most immediate benefits. Technological innovations, including wildlife crossings under highways, turtle excluder devices in fishing nets, and artificial hatcheries that maintain appropriate incubation temperatures provide targeted solutions to specific threats. Critically, sustainable economic models that value living turtles—through ecotourism, for instance—can create incentives for protection rather than exploitation. The recent shift toward seeing turtles as flagship species for broader conservation efforts helps leverage their charismatic appeal for ecosystem-wide protection. While approximately 61% of turtle and tortoise species are currently threatened with extinction according to the IUCN, their remarkable evolutionary history suggests that with adequate human support, these ancient mariners might yet navigate through the Anthropocene into a sustainable future.

Lessons from Evolutionary Champions

Turtles offer profound lessons about resilience in an ever-changing world. Their 220-million-year success story demonstrates that sometimes evolutionary conservatism—maintaining a fundamentally sound body plan—can outperform constant innovation. The turtle’s approach of investing heavily in defense and efficiency rather than speed or aggression provides a counterintuitive lesson that patience and protection can triumph over geological timescales. Their capacity to endure through dramatically different planetary conditions offers perspective on adaptability and suggests that specialization, while potentially advantageous in stable times, may create vulnerability during periods of rapid change. Perhaps most relevantly for our current biodiversity crisis, turtles remind us that evolution requires time—the very resource that modern extinction pressures often don’t provide. By understanding and protecting these living fossils, we not only preserve remarkable biological heritage but also maintain access to evolutionary strategies that have proven successful across deep time.

As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, turtles stand as both warning and inspiration. These remarkable survivors have endured across geological epochs through a combination of anatomical innovation, physiological toughness, behavioral flexibility, and reproductive resilience. Their current vulnerability to human activities highlights the unprecedented speed and scale of anthropogenic changes compared to natural processes. Yet their proven adaptability also offers hope that with appropriate conservation measures, many species can recover and continue their evolutionary journey. In protecting turtles, we acknowledge not just their intrinsic value but also our responsibility toward living monuments of evolution’s ingenuity—creatures that watched dinosaurs both rise and fall, and that might yet outlast our own species if given the chance to continue their remarkable story of survival.