Beneath the rust-colored rocks and windswept mesas of the American Southwest lies a prehistoric legacy that continues to captivate paleontologists worldwide. Among the many fossil treasures discovered in this region, few are as distinctive as Typothorax, an armored reptile that roamed the landscape during the Late Triassic period, approximately 230-200 million years ago. With its tank-like body covered in ornate bony plates and a peculiar, wide, flattened shape, Typothorax represents one of the most successful and specialized aetosaurs—an extinct group of heavily armored, herbivorous reptiles that flourished before dinosaurs dominated the planet. Its fossils, primarily found in New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas, provide a fascinating glimpse into Earth’s distant past when the Southwest was a dramatically different environment than the arid region we know today.

Taxonomic Classification and Evolutionary Context

Typothorax belongs to the group Aetosauria, a specialized clade of armored archosaurs within the larger group Pseudosuchia, which includes modern crocodilians and their extinct relatives. This taxonomic placement makes Typothorax more closely related to crocodiles than to dinosaurs, despite some superficial similarities to armored dinosaurs like ankylosaurs. The genus currently contains two recognized species: Typothorax coccinarum, the type species, and Typothorax antiquum, a slightly older and more primitive form. Aetosaurs like Typothorax represent an interesting evolutionary experiment in herbivory among early archosaurs, as most of their relatives were carnivorous. This distinct evolutionary path makes them particularly valuable for understanding the diversification of feeding strategies among Triassic reptiles and how different ecological niches were being exploited before the rise of dinosaurian dominance.

Discover your History, your Rhythm, and Important Fossil Finds

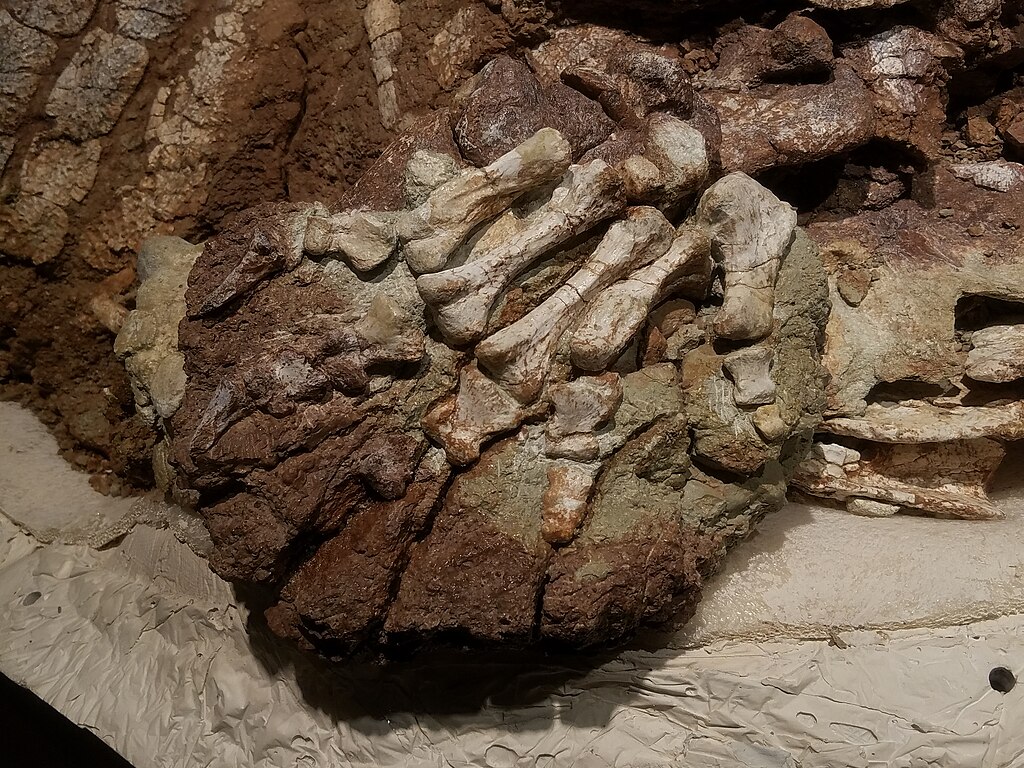

The scientific journey of Typothorax began in 1875 when paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope first described fragmentary remains from New Mexico. The genus name, derived from Greek, means “impression thorax,” referring to the distinctive patterning on its armor plates. For decades, Typothorax was known only from scattered armor fragments, leading to considerable confusion about its complete appearance and lifestyle. A significant breakthrough came in the late 20th century with the discovery of more complete specimens from the Chinle Formation in New Mexico and Arizona. Perhaps the most important find was a nearly complete skeleton unearthed at Ghost Ranch, New Mexico—the same area famous for yielding numerous specimens of the early dinosaur Coelophysis. This exceptional specimen, along with others subsequently discovered, finally allowed paleontologists to reconstruct Typothorax’s full body plan and gain insights into its biology that had remained elusive for over a century after its initial discovery.

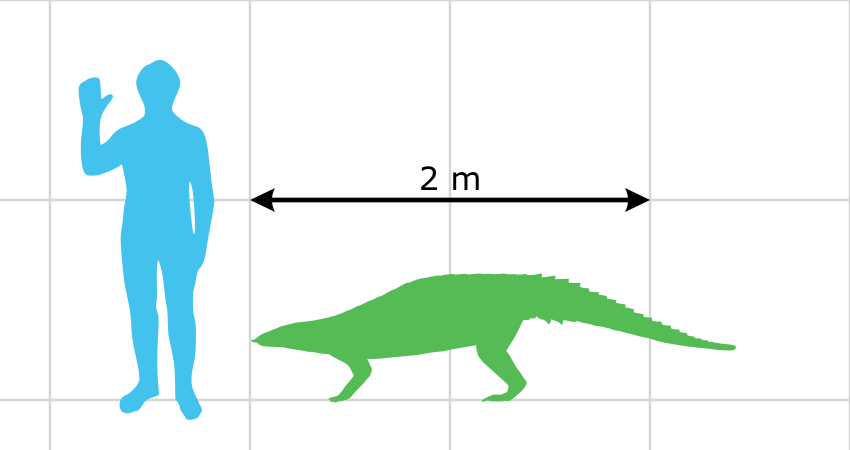

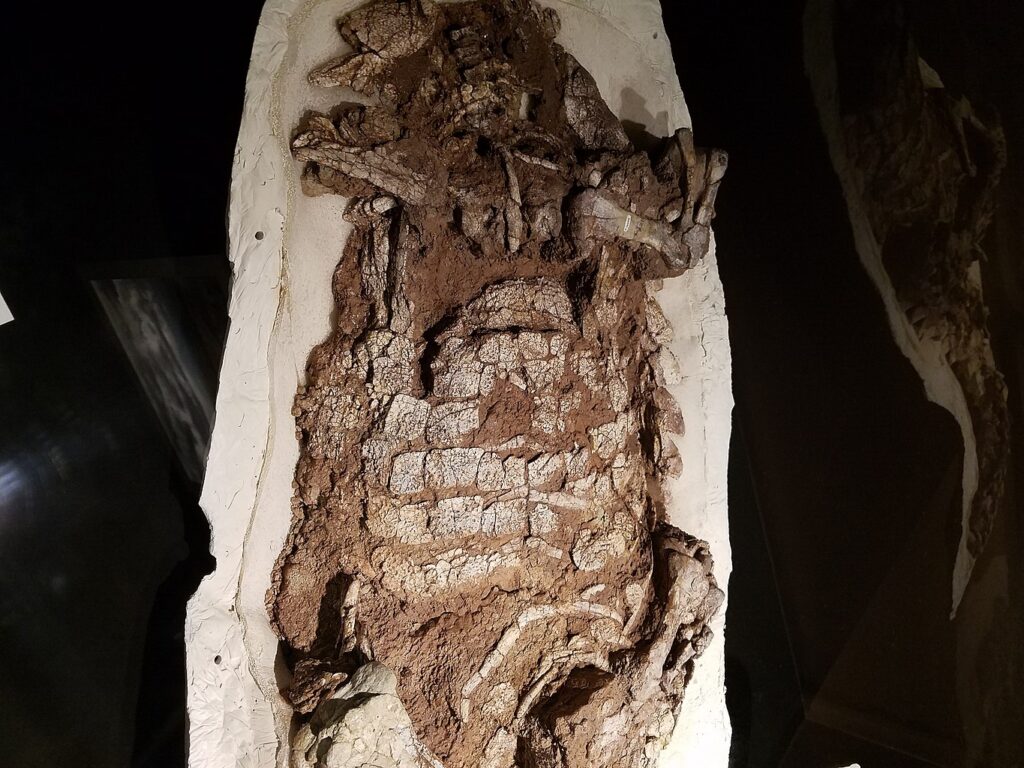

Physical Characteristics and Body Armor

Typothorax was a medium-sized aetosaur, reaching lengths of approximately 2.5 to 3 meters (8 to 10 feet), making it about the size of a modern American alligator. Its most striking feature was undoubtedly its extensive body armor, consisting of rectangular bony plates called osteoderms that covered its back, sides, limbs, and tail in overlapping rows. These osteoderms formed a continuous protective carapace, each plate adorned with distinctive pitting and radiating ridge patterns that serve as diagnostic features for species identification. The armor was arranged in regular longitudinal and transverse rows, with particularly wide plates across the mid-section giving Typothorax its characteristic broad, flattened appearance. Unlike some other aetosaurs, Typothorax had relatively short spikes projecting from its armor, primarily along the sides of its body. This extensive armoring would have provided excellent protection against the predatory rauisuchians and early dinosaurs that shared its environment, effectively making Typothorax a well-defended “tank” of the Triassic period.

Unique Skeletal Adaptations

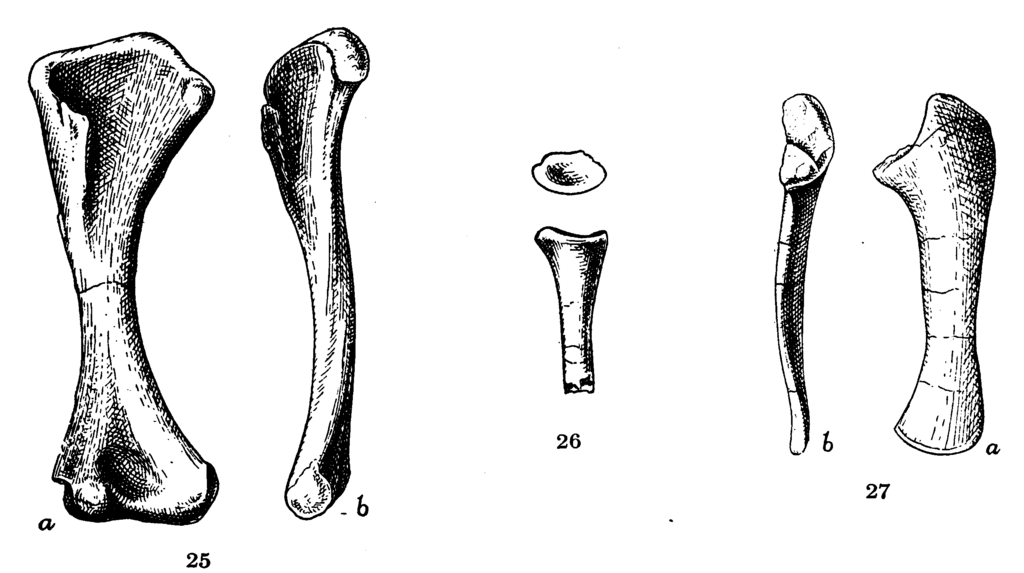

Beyond its impressive armor, Typothorax possessed several distinctive skeletal features that set it apart from other reptiles of its time. Its body was unusually wide and flat compared to most other aetosaurs, with broad hips and shoulders supporting a low-slung frame. The limbs of Typothorax showed interesting adaptations, particularly the forelimbs, which were robust with specialized claws that appear suited for digging. Unlike many other quadrupedal reptiles, Typothorax had a semi-erect posture, with limbs positioned more under the body than sprawling to the sides, though not as fully upright as in dinosaurs or mammals. The tail was moderately long and heavily armored, likely serving as both a counterbalance and defensive weapon. Perhaps most curious was Typothorax’s skull, which was relatively small compared to its body, with a distinctive upturned snout ending in a small beak-like structure. This unusual cranial morphology hints at specialized feeding behaviors that differentiated it from other contemporary herbivores.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Paleontologists believe Typothorax was primarily herbivorous, based on several lines of evidence including its dentition, jaw structure, and comparison with other aetosaurs. Its teeth were small, leaf-shaped, and seemingly adapted for cropping vegetation rather than seizing prey. The distinctive upturned snout and pig-like appearance of its muzzle suggest it may have used this specialized structure to root through soil and ground cover in search of specific plant foods, perhaps tubers, roots, or low-growing vegetation. Some researchers have proposed that Typothorax might have been specialized for consuming horsetails, ferns, and other primitive plants that were abundant in its habitat. Interestingly, the front of its mouth appears to have been edentulous (lacking teeth) and may have supported a keratinous beak similar to those of modern turtles, which would have been useful for nipping vegetation. This specialized feeding apparatus represents one of the earliest examples of herbivorous adaptations in the archosaur lineage, highlighting Typothorax’s evolutionary significance.

Habitat and Environmental Context

During the Late Triassic, when Typothorax thrived, the American Southwest bore little resemblance to today’s arid landscape. The region was situated much closer to the equator due to continental drift and experienced a tropical to subtropical climate characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons. Typothorax inhabited lowland environments associated with rivers, floodplains, and seasonal lakes that made up the extensive Chinle depositional system. These environments supported diverse plant communities dominated by ferns, cycads, ginkgoes, and early conifers, with true flowering plants still millions of years in the future. Fossil evidence indicates that these habitats were prone to periodic flooding and drought, suggesting that Typothorax needed to be adaptable to changing conditions. The distribution of Typothorax fossils primarily within certain facies of the Chinle Formation indicates these animals may have preferred specific microhabitats within this broader ecosystem, possibly areas close to water sources that would have supported the lush vegetation they depended upon for food.

Paleobiology and Growth Patterns

Studies of Typothorax growth patterns, conducted through histological analysis of bone samples, reveal fascinating aspects of its life history. Like many reptiles, Typothorax appears to have grown relatively quickly in its early years before reaching a growth plateau as an adult. The bone structure shows distinct growth rings, similar to tree rings, which indicate seasonal variations in growth rate—likely faster during favorable conditions and slower during more challenging periods. Unlike many modern reptiles, however, the bone microstructure of Typothorax shows relatively dense vascularization, suggesting a metabolic rate that may have been somewhat elevated compared to typical ectothermic (“cold-blooded”) reptiles. Juvenile specimens of Typothorax are relatively rare in the fossil record, but those that have been found indicate that young individuals already possessed the characteristic armor of adults, albeit with less developed ornamentation patterns. This suggests that even young Typothorax were well-protected against predation, which may explain their successful persistence in ecosystems dominated by large predatory archosaurs.

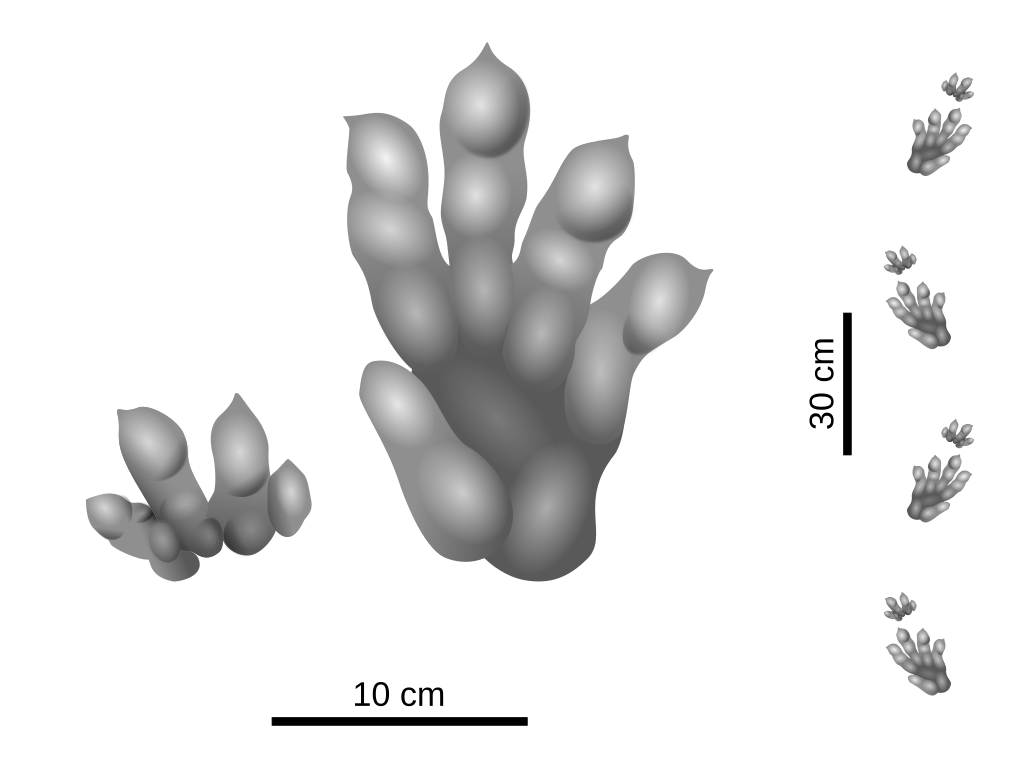

Locomotion and Movement Capabilities

The locomotive abilities of Typothorax have been the subject of considerable scientific interest, particularly given its unusual body proportions and heavy armor. Trackways attributed to aetosaurs, potentially including Typothorax, show that these animals walked with a semi-erect gait, not fully sprawling like many reptiles, but not as upright as dinosaurs. Its wide body and relatively short legs suggest it was not built for speed but rather for stability and efficient low-energy movement. Biomechanical studies indicate that Typothorax would have been capable of sustained walking at slow to moderate speeds, but unlikely to engage in rapid running or chasing behavior. The robust forelimbs with their specialized claws point to digging capabilities, potentially for foraging or possibly for constructing simple burrows for shelter. Some paleontologists have suggested that Typothorax might have been semi-aquatic, using waterways for more efficient transportation and to escape predators, though direct evidence for this lifestyle remains limited. The wide, flat body would have provided stability in water, but the heavy armor would have made it a poor swimmer compared to specialized aquatic reptiles of the period.

Social Behavior and Reproduction

The social structure and reproductive biology of Typothorax remain largely speculative, as direct fossil evidence for these aspects of its life history is scarce. However, some inferences can be drawn from their fossil distribution and comparison with modern reptiles. The occasional discovery of multiple Typothorax specimens nearby suggests these animals may have at least tolerated each other’s presence, perhaps gathering in loose aggregations around water sources or particularly productive feeding grounds. As archosaurs, Typothorax likely reproduced by laying eggs, though no definitive aetosaur eggs or nests have been identified in the fossil record to date. Based on the general pattern observed in archosaurs, Typothorax probably exhibited limited parental care, with hatchlings being relatively precocial and capable of fending for themselves shortly after hatching. The substantial armor present even in juvenile specimens would have provided vital protection during this vulnerable life stage, potentially compensating for the absence of extended parental protection.

Ecological Relationships and Predators

Typothorax occupied a specific ecological niche as a medium-sized herbivore in Late Triassic ecosystems, coexisting with a diverse assemblage of other reptiles, including early dinosaurs, large amphibians, and various other archosaurs. Despite its formidable armor, Typothorax still faced predation threats from the apex predators of its time, particularly large rauisuchians like Postosuchus, which possessed powerful jaws capable of crushing even armored prey. Fossil evidence from the Chinle Formation shows that Typothorax shared its habitat with other aetosaur genera such as Desmatosuchus and Paratypothorax, suggesting potential resource partitioning among these armored herbivores, perhaps through different feeding specializations or microhabitat preferences. As a primary consumer, Typothorax would have played an important role in its ecosystem’s energy flow, converting plant material into animal tissue and serving as potential prey for larger carnivores. Its extensive armor and relatively large adult size suggest that mature Typothorax individuals might have enjoyed a degree of protection from all but the largest predators, potentially allowing them to exploit feeding opportunities in more exposed areas than unarmored herbivores.

Extinction and Evolutionary Legacy

Typothorax and other aetosaurs disappeared from the fossil record by the end of the Triassic period, approximately 201 million years ago, coinciding with one of Earth’s major extinction events. This end-Triassic extinction eliminated many archosaur lineages and set the stage for dinosaur dominance in terrestrial ecosystems throughout the subsequent Jurassic period. The exact causes of Typothorax’s extinction remain debated, but likely involved a combination of climate change, habitat alteration, and competition with more derived herbivores, including early dinosaurs. Although Typothorax left no direct descendants, its evolutionary experiments with herbivory and armor development represent parallel adaptations to those later seen in various dinosaur groups like ankylosaurs and stegosaurs, demonstrating convergent evolution of similar traits in response to similar selective pressures. While superficially resembling modern armadillos or even armored dinosaurs, Typothorax represents an entirely separate evolutionary trajectory that ultimately ended without leaving modern descendants, a reminder of the many evolutionary paths that have flourished and faded throughout Earth’s history.

Significance in Paleontological Research

Typothorax holds special significance in paleontological research for several reasons beyond its distinctive appearance. As one of the more completely known aetosaurs, it serves as an important reference point for understanding this entire group of armored archosaurs. The abundance of Typothorax fossils in certain formations of the American Southwest has made it a valuable biostratigraphic indicator, helping geologists determine the relative age of rock layers where its remains are found. Moreover, the distinctive patterning on Typothorax osteoderms is so characteristic that even fragmentary armor pieces can often be identified to genus level, making it useful for establishing correlations between geographically separated fossil deposits. Beyond its taxonomic and stratigraphic utility, Typothorax provides valuable insights into early archosaur herbivory, representing one of several independent evolutionary experiments with plant-eating adaptations among Triassic reptiles. The study of Typothorax continues to contribute to our understanding of ecological diversification during this critical period in Earth’s history, when the foundations for modern terrestrial ecosystems were being established.

Cultural Impact and Public Awareness

While not as widely recognized as dinosaurs in popular culture, Typothorax has gradually gained visibility in museum exhibitions and paleontological education programs focused on the Triassic period. Full-scale reconstructions of this unusual reptile can be found in several natural history museums, particularly those in the American Southwest, where its fossils are commonly discovered. The New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque features Typothorax prominently in its Triassic exhibits, showcasing this distinctive local prehistoric resident. In recent years, Typothorax has been included in several books and documentaries about prehistoric life before the dinosaur age, helping to broaden public awareness of the diverse reptilian fauna that preceded and coexisted with early dinosaurs. Its strange appearance—combining aspects reminiscent of turtles, crocodiles, and armadillos into a unique form—makes Typothorax particularly intriguing to museum visitors and helps illustrate the remarkable diversity of evolutionary adaptations that have emerged throughout Earth’s history. As interest in non-dinosaurian prehistoric reptiles continues to grow, Typothorax serves as an excellent ambassador for the often-overlooked world of Triassic archosaurs.

Conclusion

The story of Typothorax provides a fascinating window into Earth’s distant past, revealing a world where strange armored reptiles roamed landscapes that would eventually transform into the American Southwest we know today. Neither dinosaur nor crocodile, but related to the latter, Typothorax represents a successful evolutionary experiment—a specialized herbivore that thrived for millions of years before disappearing during the tumultuous changes that marked the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. Its distinctive armor, unusual body shape, and specialized feeding adaptations showcase the remarkable diversity of forms that evolved among archosaurs during this critical period in Earth’s history. As paleontologists continue to unearth and study Typothorax fossils from the colorful badlands of the Southwest, our understanding of this curious creature and its prehistoric world continues to expand, adding rich detail to the complex tapestry of life that existed before the age of dinosaurs.