For over a century, paleontologists have been piecing together the complex lives of dinosaurs that roamed Earth millions of years ago. While Hollywood has often portrayed dinosaurs as solitary predators or simple herding animals, recent evidence suggests their social behaviors were far more sophisticated than previously thought. One of the most fascinating questions emerging from modern paleontology is whether certain dinosaur species developed social structures complex enough to form what we might recognize as family units. Through fossil evidence, trackways, nesting sites, and comparative studies with modern animals, scientists are uncovering compelling evidence that many dinosaurs may have engaged in complex social behaviors, including parental care and group living arrangements that resemble family structures. This article explores what we know about dinosaur sociality and the evidence for family formations among these ancient reptiles.

The Challenges of Studying Dinosaur Social Behavior

Studying the social behavior of extinct animals presents unique challenges that don’t exist when observing living species. Paleontologists can’t directly observe dinosaur interactions, making it necessary to rely on indirect evidence from the fossil record. Fossilized bones, nests, eggs, and trackways provide important clues, but they represent only snapshots of moments frozen in time rather than continuous observation. Additionally, behavior doesn’t fossilize, meaning scientists must make careful inferences based on physical evidence and comparisons with modern relatives like birds and crocodilians. Taphonomic processes—how organisms decay and become fossilized—can also create misleading patterns that might be mistaken for social groupings when they actually resulted from flooding events or other natural processes that concentrated remains after death. Despite these challenges, paleontologists have developed increasingly sophisticated methods to distinguish genuine evidence of sociality from preservation artifacts.

Evidence from Mass Death Assemblages

One of the most compelling lines of evidence for dinosaur sociality comes from mass death assemblages, where multiple individuals of the same species are found together in a single location. The Centrosaurus bone beds in Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, contain thousands of individuals that appear to have died together, suggesting they lived in large herds. Similarly, assemblages of the small theropod Coelophysis at Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, include individuals of different ages found together, potentially indicating social groupings. Perhaps most striking is the “Fighting Dinosaurs” specimen from Mongolia, showing a Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in combat at the moment of their death, with the Velociraptor’s foot claw embedded in the Protoceratops’s neck. Nearby discoveries of multiple Velociraptor specimens have led some researchers to speculate these predators may have hunted in coordinated groups, though this remains debated. When mass assemblages contain individuals of different growth stages and show no evidence of being transported by water or other natural forces, they provide strong evidence for social living.

Nesting Sites and Parental Care

Nesting sites offer some of the most direct evidence for family-like structures among dinosaurs. The discovery of adult Maiasaura (“good mother lizard”) fossils in association with nests, hatchlings, and juveniles in Montana suggests these hadrosaurs provided extended care for their young. The nests contained worn teeth from juveniles too young to feed themselves, indicating parents may have brought food to the nest. Oviraptor specimens have been found in brooding positions atop nests, suggesting they incubated their eggs similar to modern birds. This behavior was so dedicated that some individuals appear to have been buried alive while protecting their nests during sandstorms. In Argentina, sauropod nesting grounds show evidence of colonial nesting, where many individuals laid eggs in the same location year after year, suggesting complex social structures. Perhaps most compelling are Citipati specimens found with their arms spread over their nests in a protective posture, showing these theropods died while sheltering their developing offspring from the elements.

Trackway Evidence of Group Behavior

Fossilized footprints, or trackways, provide a direct record of dinosaur movement patterns that can reveal social dynamics. Multiple parallel trackways of the same species moving in the same direction at the same time strongly suggest coordinated group movement. Hadrosaur trackways from Canada and the United States show evidence of herds containing adults and juveniles traveling together, with smaller footprints positioned in the center of the group, protected by larger individuals—a pattern seen in modern protective family groups. Sauropod trackways from the Morrison Formation reveal similar patterns of adults surrounding juveniles. Some theropod trackways show multiple individuals moving in coordination, potentially representing hunting parties or family groups. Importantly, trackways can capture behavioral moments that skeletal remains cannot, such as spacing between individuals, direction of travel, and speed, offering unique insights into how dinosaurs interacted while alive. When multiple growth stages appear in coordinated movement patterns, this provides compelling evidence for family-based social structures.

Maiasaura: The “Good Mother Lizard”

Maiasaura peeblesorum stands as one of the best-documented examples of parental care among dinosaurs, earning its name which translates to “good mother lizard.” Discovered by paleontologist Jack Horner in the Two Medicine Formation of Montana, these duck-billed dinosaurs left behind extensive evidence of family structures. The Maiasaura nesting grounds contained over 200 individual nests arranged in patterns similar to modern colonial nesting birds, spaced about seven meters apart—close enough for community protection but far enough to allow adults to move between nests. Each bowl-shaped nest contained approximately 30-40 eggs, and fossil evidence reveals that hatchlings remained in the nest until they nearly doubled in size, growing from about 30 cm to 1 meter before leaving. The leg bones of these juveniles show underdeveloped muscle attachment sites, suggesting they were not capable of extensive foraging on their own, indicating adults must have brought food to the nest. This complex picture of extended care, colonial nesting, and community structure strongly resembles family units seen in modern animals.

Theropod Dinosaurs and Family Bonds

Despite their fearsome reputation as predators, theropod dinosaurs—the group that includes Tyrannosaurus rex and modern birds—have yielded substantial evidence for family-like social structures. The discovery of adult Troodon and Oviraptor specimens positioned atop nests in brooding postures suggests these dinosaurs were actively caring for their eggs at the time of death, much like modern birds. In Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, paleontologists discovered a remarkable specimen of Citipati osmolskae (an oviraptorid) that perished while protecting its nest from a sandstorm, its arms spread in a protective posture over its eggs—a compelling snapshot of parental dedication. Multiple specimens of juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex found in relative proximity have led some researchers to hypothesize that even these apex predators may have lived in family groups during adolescence. Perhaps most telling is a remarkable fossil from China’s Liaoning Province showing an adult Philoraptorr pilgrimage with 24 young juveniles, potentially representing a family group caught in a volcanic eruption, though some debate remains about whether this assemblage represents a genuine family or an opportunistic feeding scenario.

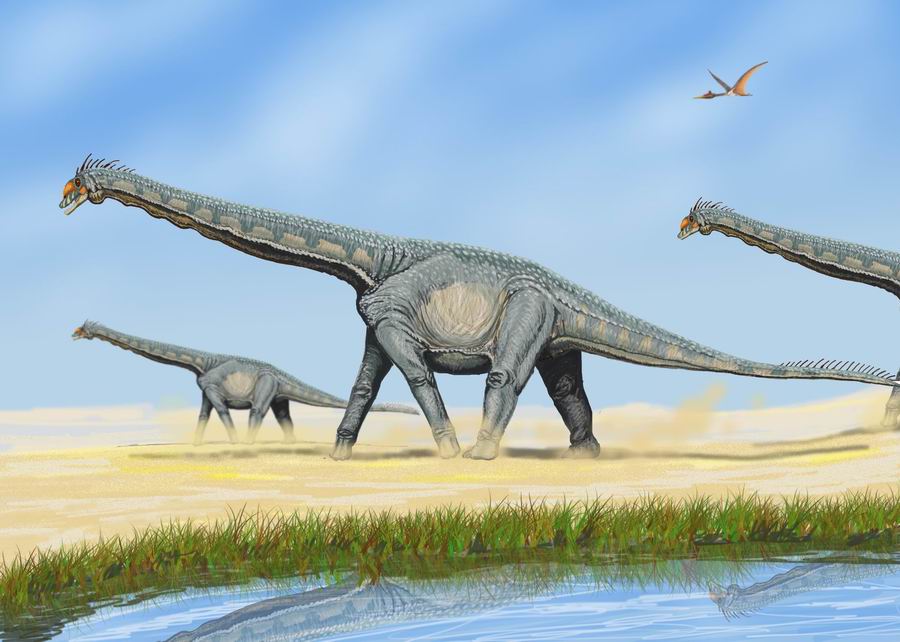

Sauropod Dinosaurs: Herds and Potential Family Groups

The enormous sauropod dinosaurs, famous for their long necks and massive size, have left evidence suggesting they formed complex social groupings that may have included family units. Trackway evidence from the Morrison Formation shows patterns of adults walking alongside juveniles, sometimes with smaller tracks positioned between larger ones in a protective formation. In Argentina’s Auca Mahuevo site, thousands of sauropod eggs have been discovered in distinct nesting colonies, with eggs laid in neat rows within circular nests. The organization of these nesting grounds suggests cooperative breeding behaviors, where many individuals returned to the same locations year after year. Analysis of growth rings in sauropod bones indicates that juveniles grew at astonishingly rapid rates, which some paleontologists interpret as evidence they received extensive parental provisioning and protection. While direct evidence of sauropod parental care remains limited, their colonial nesting behavior, coordinated movement patterns, and the presence of mixed-age herds suggest social structures that likely included some form of extended family groupings for protection and resource sharing.

Evidence from Growth Patterns and Bone Beds

The study of dinosaur growth patterns through bone histology has revealed important insights into potential family structures. By examining growth rings (similar to tree rings) in fossil bones, paleontologists can determine how quickly dinosaurs grew and when they reached sexual maturity. Many dinosaur species show a pattern of rapid juvenile growth followed by slowed growth at maturity, suggesting a life history strategy that included extended parental care during the vulnerable rapid-growth phase. The famous Centrosaurus bone beds of Alberta contain thousands of individuals that appear to have died together during a flooding event, with specimens representing various growth stages from juveniles to adults. Statistical analysis of these bone beds shows non-random age distributions consistent with natural family groupings rather than random aggregations. Similarly, the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry in Utah, with its high concentration of Allosaurus remains, shows evidence of multiple growth stages present together, though debate continues about whether this represents social groupings or simply a predator trap that caught individuals of different ages. These growth-based analyses provide a demographic perspective on dinosaur sociality that complements direct fossil evidence.

Dinosaur Parenting Strategies Compared to Modern Animals

Examining dinosaur parental care through the lens of modern animals provides valuable context for interpreting fossil evidence. Dinosaurs evolved within Archosauria, a group that includes both crocodilians and birds—animals with markedly different parenting approaches. Modern crocodilians exhibit maternal care, with females guarding nests and even carrying hatchlings in their mouths, but this care is relatively brief. Birds, as dinosaur descendants, show extensive parental care, with many species feeding and protecting offspring for extended periods. The evidence from dinosaur fossils suggests parenting strategies across the spectrum. Some dinosaurs, like certain sauropods, may have employed a more crocodilian-like strategy of guarding nests but providing limited post-hatching care, essentially employing a “precocial” strategy where hatchlings were relatively independent. Others, like Maiasaura and oviraptorids, appear to have employed more bird-like “altricial” strategies, with extended care of relatively helpless young. This diversity of approaches makes sense given dinosaurs’ 165-million-year evolutionary history and wide range of ecological niches, suggesting that family structures likely varied significantly across different dinosaur groups.

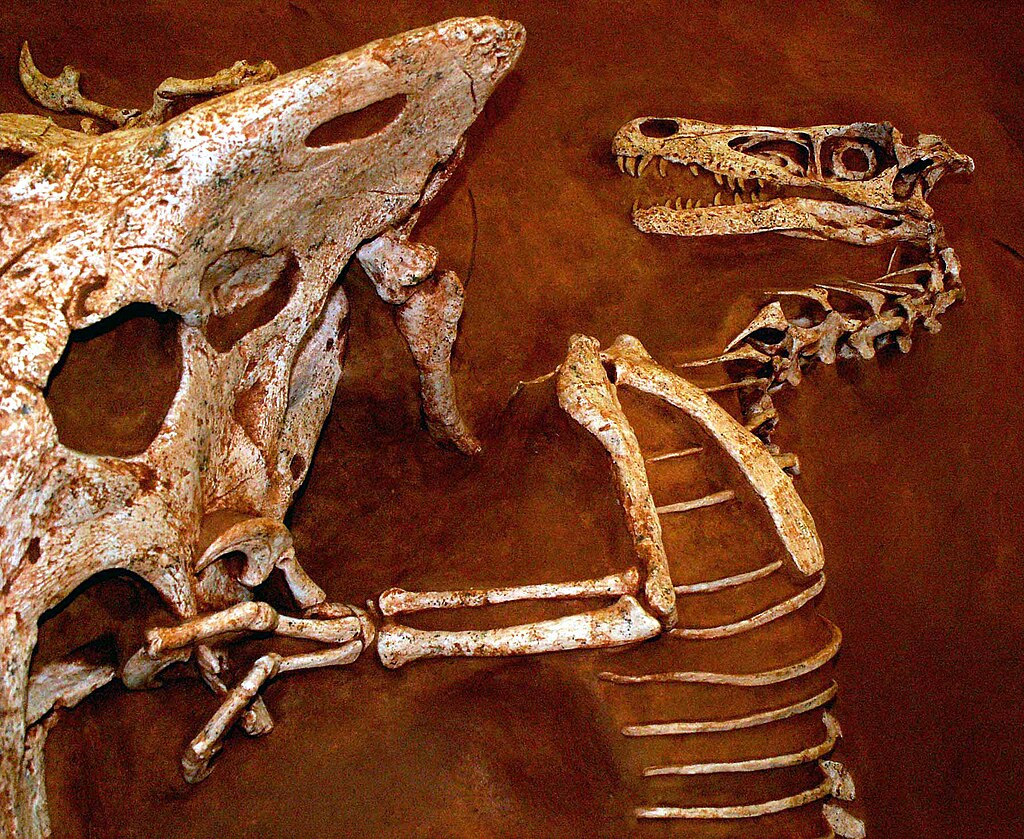

The Case of Deinonychus and Pack Hunting

Deinonychus antirrhopus, made famous as the model for the “raptors” in Jurassic Park (though considerably larger than the film portrayed), has sparked significant debate about cooperative social behavior in theropod dinosaurs. Paleontologist John Ostrom’s discoveries in the 1960s found multiple Deinonychus individuals associated with a single Tenontosaurus prey animal, suggesting possible pack hunting behavior. More recent examinations of bone beds containing multiple Deinonychus specimens have revealed individuals of different growth stages preserved together, potentially representing family groups rather than unrelated packs. The large, curved “killing claw” on each foot seems well-adapted for taking down prey larger than an individual Deinonychus could handle alone, providing a biomechanical argument for social hunting. Tooth-marked bones from prey animals sometimes show multiple attack points that would be difficult for a single predator to inflict simultaneously. While some paleontologists remain skeptical, suggesting these associations might represent mob feeding rather than coordinated hunting, the evidence collectively suggests Deinonychus may have hunted in family groups similar to some modern predators like wolves or lions, where related individuals cooperate to bring down larger prey.

Modern Discoveries and Technological Advances

Recent technological advances have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur sociality and family structures. CT scanning of fossil eggs has revealed embryonic dinosaurs in various developmental stages, providing insights into growth rates and hatching strategies without destroying specimens. Chemical analysis of fossil bones using techniques like rare earth element analysis can now determine whether dinosaurs found together actually lived together or were transported after death. Powerful computer modeling has enabled researchers to analyze trackway patterns mathematically, distinguishing random aggregations from coordinated group movements with statistical certainty. Advances in comparative phylogenetics allow scientists to place dinosaur behavior in evolutionary context by comparing multiple lines of evidence across related species. Perhaps most exciting is the application of synchrotron radiation analysis, which can reveal microscopic details of bone structure and even preserved soft tissues, providing unprecedented insights into dinosaur physiology and development. These technological innovations continue to strengthen the case for complex social structures, including family units, among many dinosaur species by providing multiple independent lines of evidence that point toward similar conclusions.

Debated Cases and Scientific Disagreements

Not all paleontologists agree on the interpretation of evidence for dinosaur family units, with several high-profile cases generating ongoing scientific debate. The interpretation of Tyrannosaurus rex social behavior remains particularly contentious, with some researchers arguing that multiple specimens found together represent family groups, while others suggest these aggregations resulted from coincidental deaths around concentrated food sources. The famous “fighting dinosaurs” specimen showing Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in combat has been cited as evidence both for and against pack hunting behavior. Some researchers interpret nearby Velociraptor specimens as evidence of coordinated attacks, while others argue the evidence is insufficient to distinguish between social hunting and opportunistic mob feeding. The Mapusaurus bone bed from Argentina contains multiple individuals of this massive carcharodontosaurid, which some interpret as evidence of pack behavior in giant theropods, while others suggest it may represent a temporary aggregation. These ongoing debates highlight the challenge of interpreting behavior from fossil evidence and reflect the scientific process at work as researchers continue to test hypotheses about dinosaur sociality against new discoveries and analytical methods.

Conclusion: The Growing Evidence for Dinosaur Families

While definitive proof of dinosaur family structures remains elusive due to the inherent limitations of the fossil record, the cumulative evidence strongly suggests many dinosaur species lived in social groups that included extended care of offspring and multi-generational associations. The most compelling cases come from nesting grounds showing adults in direct association with eggs and juveniles, trackways demonstrating coordinated movement of mixed-age groups, and mass death assemblages containing individuals of various growth stages. The discovery that many dinosaur species exhibited extended parental care challenges older perceptions of these animals as solitary or simplistic in their social behaviors. As research techniques continue to advance, our understanding of dinosaur sociality grows increasingly sophisticated, revealing these ancient reptiles as complex, socially intelligent creatures. Perhaps the most profound insight from this research is the recognition that family structures and parental care evolved long before humans—or even mammals—appeared on Earth, representing fundamental survival strategies that have deep evolutionary roots stretching back hundreds of millions of years. The dinosaur family, it seems, was very much a reality.