The sudden extinction of non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago marks one of the most dramatic transitions in Earth’s biological history. While the catastrophic asteroid impact at the end of the Cretaceous period has long been identified as the primary culprit behind this mass extinction, recent scientific evidence has sparked an intriguing debate: Were dinosaurs already experiencing a gradual decline before the asteroid delivered the final blow? This article explores the fascinating and complex evidence surrounding dinosaur diversity, environmental changes, and evolutionary patterns in the late Cretaceous period, examining whether these magnificent creatures were thriving or struggling when their 165-million-year reign came to an abrupt end.

The Traditional Extinction Narrative

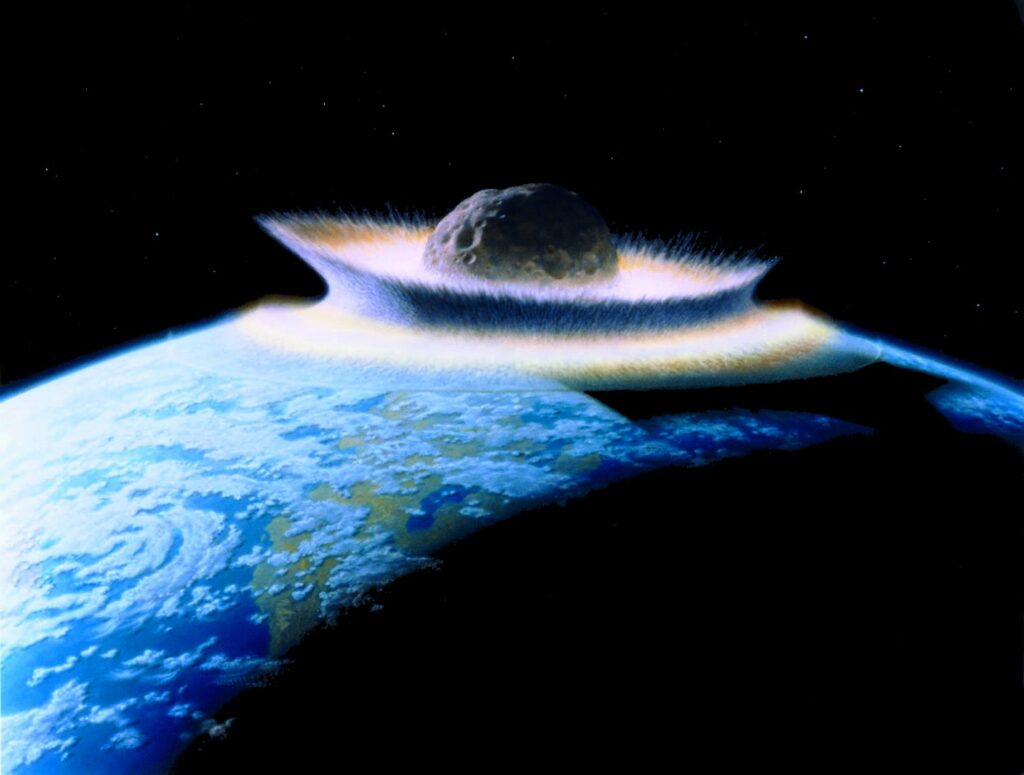

The conventional view of dinosaur extinction centers on the Chicxulub impact event, when an asteroid approximately 10-15 kilometers in diameter crashed into what is now Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. This cataclysmic event triggered worldwide climate disruption, including tsunamis, wildfires, and an “impact winter” that blocked sunlight for years. The rapid environmental changes that followed devastated ecosystems globally, eliminating roughly 75% of all species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. This dramatic narrative—of dinosaurs thriving until being suddenly wiped out by a cosmic accident—has dominated scientific understanding and popular imagination for decades. However, a growing body of research suggests the story might be more nuanced, with dinosaurs potentially experiencing challenges well before the asteroid struck.

Examining the Fossil Record

The fossil record provides our primary window into dinosaur diversity through time, though it comes with significant limitations and biases. Fossilization itself is an extremely rare event, with only a tiny fraction of organisms ever becoming preserved. Additionally, geological processes and human collecting biases further distort our picture of ancient biodiversity. When paleontologists analyze dinosaur fossils from the late Cretaceous (approximately 100-66 million years ago), they must account for these preservation biases through sophisticated statistical methods. Some studies indicate apparent declines in dinosaur diversity during the final 10 million years before the extinction, while others suggest stable or even increasing diversity. This discrepancy has fueled significant debate about whether observed patterns represent genuine biological trends or merely artifacts of an imperfect fossil record.

The Deccan Traps Controversy

While the asteroid impact receives the most attention, another major geological event was unfolding during the late Cretaceous: the formation of the Deccan Traps in what is now India. This massive volcanic province produced one of the largest lava flows in Earth’s history, erupting over approximately one million years and coinciding with the end-Cretaceous extinction. The eruptions released enormous quantities of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and other gases into the atmosphere, potentially causing significant climate disruption. Some researchers propose that Deccan volcanism had already begun stressing global ecosystems, including dinosaur habitats, before the asteroid impact. This “one-two punch” hypothesis suggests the asteroid delivered the final blow to already-vulnerable dinosaur populations that had been weakened by volcanic-induced climate change.

Dinosaur Diversity Patterns

Recent comprehensive analyses of the dinosaur fossil record have yielded conflicting results regarding late Cretaceous diversity trends. A landmark 2016 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that dinosaurs were already declining for up to 40 million years before the extinction, with fewer new species evolving than existing ones disappearing. However, subsequent research in 2018 challenged these findings, arguing that when accounting for gaps in the fossil record, dinosaurs showed no clear decline before the asteroid impact. Instead, different dinosaur groups exhibited varying patterns—some thriving while others struggled. For instance, duck-billed hadrosaurs and horned ceratopsians appeared to be flourishing in North America during the very end of the Cretaceous, evolving new species and expanding their ranges, while other groups like ankylosaurs showed less diversity.

Geographic Variation in Dinosaur Health

An important nuance in the decline debate involves geographic differences in dinosaur communities across the late Cretaceous world. The most complete fossil record from this time comes from western North America, particularly the Hell Creek Formation, which preserves a rich dinosaur fauna right up to the extinction boundary. These ecosystems show impressive dinosaur diversity, with multiple species of tyrannosaurs, ceratopsians, hadrosaurs, and other groups coexisting. However, the picture from other continents is less clear due to fewer fossil sites. Some evidence from Europe suggests dinosaur diversity was lower in the final stages of the Cretaceous, while data from South America and Asia present mixed signals. This geographic variation raises the possibility that dinosaurs may have been declining in some regions while thriving in others, complicating the global narrative of their pre-extinction status.

Climate Change in the Late Cretaceous

The late Cretaceous period experienced significant climate fluctuations that may have influenced dinosaur populations. Global temperatures during this time were considerably warmer than today, with minimal polar ice and high sea levels creating extensive shallow seas across continental interiors. However, evidence indicates that the final 10 million years of the Cretaceous saw cooling trends and sea level fluctuations that altered habitats and may have stressed some dinosaur communities. Pollen records and plant fossils suggest changing vegetation patterns, potentially affecting herbivorous dinosaurs and, by extension, their predators. These climate shifts occurred gradually enough that they might not have posed an extinction threat by themselves, but they could have reduced population resilience, making dinosaurs more vulnerable to the subsequent catastrophic impact.

Ecological Relationships and Competition

Dinosaurs existed within complex ecological networks, and changes in these relationships might have influenced their late Cretaceous status. Some researchers have proposed that increasing competition from mammals, which were diversifying throughout the Cretaceous despite remaining relatively small, may have placed pressure on smaller dinosaur species. Similarly, the evolution of flowering plants (angiosperms), which expanded dramatically during the late Cretaceous, transformed ecosystems and may have affected plant-eating dinosaurs adapted to earlier vegetation types. Dinosaurs themselves were also evolving, with potential competition between different dinosaur groups as new adaptations emerged. For example, the rise of large duck-billed hadrosaurs with sophisticated chewing abilities might have outcompeted some other herbivorous dinosaurs in certain habitats, creating ecosystem shifts even before the asteroid impact.

The Molecular Clock Perspective

Beyond the fossil record, scientists have employed molecular clock techniques to estimate evolutionary relationships and divergence times among modern birds—the living descendants of theropod dinosaurs. These genetic analyses provide an independent line of evidence about dinosaur evolutionary patterns. Some molecular studies suggest that modern bird lineages began diversifying before the end-Cretaceous extinction, indicating that avian dinosaurs, at least, were experiencing evolutionary innovations during this period. The survival and subsequent radiation of birds after the extinction event demonstrates that certain dinosaur adaptations proved remarkably resilient. While molecular clock data can’t directly address whether non-avian dinosaurs were declining, it does suggest that the dinosaur evolutionary story extends beyond the extinction boundary, with the avian branch continuing to thrive and diversify into thousands of modern bird species.

Dinosaur Physiology and Adaptability

The question of dinosaur decline relates closely to debates about their physiology and adaptability. Increasing evidence suggests many dinosaurs possessed bird-like features, including rapid growth, high metabolic rates, and in some cases, feathers or proto-feathers for insulation. These physiological traits would have influenced how dinosaurs responded to environmental challenges in the late Cretaceous. Some researchers argue that dinosaurs possessed considerable adaptability, as demonstrated by their geographic spread across virtually all continents and environments, from polar regions to deserts. Their 165-million-year evolutionary history certainly showcases impressive resilience through multiple environmental changes. However, specialized adaptations might also have created vulnerabilities when faced with rapid, catastrophic change. The balance between dinosaur adaptability and specialization remains a crucial factor in assessing whether they were in decline before the asteroid impact.

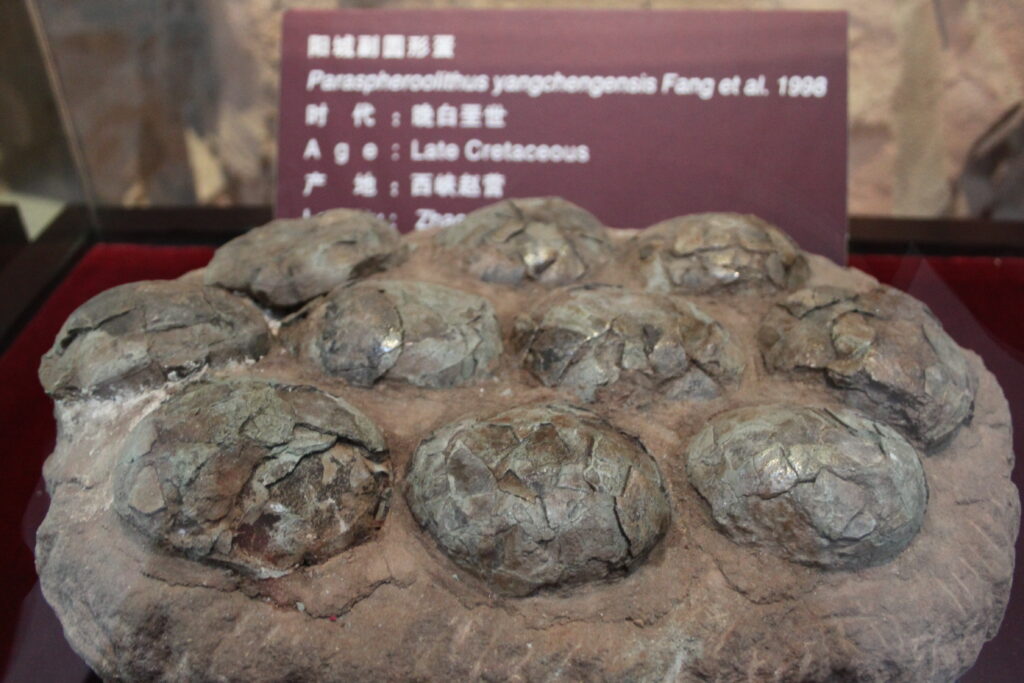

The Case for Pre-Impact Decline

Proponents of the pre-extinction decline hypothesis point to several lines of evidence beyond raw diversity counts. Some studies suggest dinosaur morphological disparity—the variety of body forms and ecological functions—was decreasing in the late Cretaceous, even if species numbers remained stable. This could indicate diminishing ecological innovation and evolutionary stagnation. Additionally, certain dinosaur groups appear to have experienced range contractions, becoming more geographically restricted than in earlier periods. Analysis of dinosaur egg diversity from China and other regions has suggested reproductive stress in some populations. Another argument involves community structure changes, with some late Cretaceous ecosystems showing altered predator-prey ratios or simplified food webs compared to earlier periods. Collectively, these signals might indicate dinosaur ecosystems were experiencing stress and restructuring before the asteroid impact, potentially making them more vulnerable to catastrophic disruption.

The Case Against Pre-Impact Decline

Despite evidence suggesting potential stress, many paleontologists remain unconvinced that dinosaurs were in systematic decline before the asteroid impact. They point to the remarkable diversity of dinosaurs preserved in formations like Hell Creek, where at least 20 different non-avian dinosaur species coexisted right up to the extinction boundary. These communities included both large and small species, herbivores and carnivores, suggesting intact and functioning ecosystems. Statistical analyses that account for the incompleteness of the fossil record often fail to detect significant diversity declines when sampling biases are corrected. Dinosaur reproduction also appears successful in the latest Cretaceous, with abundant egg sites and evidence of nesting behavior continuing until the extinction. Perhaps most compelling is the abruptness of the extinction itself—virtually no non-avian dinosaur fossils are found above the impact layer, suggesting a sudden rather than gradual disappearance, which aligns better with a catastrophic event affecting otherwise healthy populations.

Regional Variations in the Extinction Pattern

The end-Cretaceous extinction displays intriguing regional variations that complicate the decline debate. In North America, the extinction appears extremely abrupt, with diverse dinosaur communities vanishing precisely at the impact boundary marked by a thin layer rich in impact-derived minerals like iridium. However, in some regions of Europe, Asia, and particularly India, the pattern is less clear-cut. Some studies of Indian dinosaur-bearing formations suggest potential decreases in diversity before the impact layer, though these findings remain contested due to dating uncertainties and preservation issues. The proximity of Indian dinosaur communities to the Deccan Traps volcanic activity might have created regional stresses that weren’t experienced globally. These geographic variations highlight the importance of considering local contexts when evaluating dinosaur decline hypotheses, as different populations may have experienced different pressures based on their environmental circumstances.

Implications for Understanding Mass Extinctions

The debate about dinosaur decline before the asteroid impact carries broader implications for how we understand mass extinctions and ecosystem vulnerability. If dinosaurs were already declining due to environmental stressors, it suggests that mass extinctions might result from the coincidence of long-term pressures with sudden catastrophic events—a sobering perspective when considering current biodiversity threats. Alternatively, if dinosaurs were thriving until the asteroid struck, it emphasizes how even healthy ecosystems can collapse when faced with sufficiently severe disruptions. Either scenario offers valuable insights as we face current environmental challenges, including climate change, habitat destruction, and pollution. The dinosaur extinction debate reminds us that ecosystem resilience has limits, whether those limits are approached gradually through accumulating stresses or exceeded suddenly through catastrophic events.

The Ongoing Scientific Debate

The question of dinosaur decline remains an active area of scientific research and debate, with new evidence continuously refining our understanding. Recent methodological advances—including more sophisticated statistical approaches to fossil record analysis, improved dating techniques, and better understanding of preservation biases—are helping scientists develop more nuanced pictures of late Cretaceous ecosystems. International collaborations are expanding fossil collection beyond the well-studied North American formations to improve global coverage. Meanwhile, interdisciplinary approaches combining paleontology with ecology, climate science, and geochemistry are creating more comprehensive models of the extinction dynamics. As with many complex scientific questions, the dinosaur decline debate may not resolve into a simple yes-or-no answer, but rather a more textured understanding of how different dinosaur groups in different regions responded to varying environmental pressures before the final catastrophe.

Conclusion

The question of whether dinosaurs were declining before the asteroid impact remains one of paleontology’s most intriguing debates. Current evidence suggests a complex reality—neither simple thriving nor uniform decline accurately captures the state of dinosaur life in the late Cretaceous. Different dinosaur groups were experiencing different trajectories, with some flourishing while others struggled, and regional variations created a patchwork of conditions across the planet. Environmental changes, including climate fluctuations and ecosystem transformation, were certainly occurring, potentially stressing some populations while creating opportunities for others. What seems increasingly clear is that the asteroid impact represented an extraordinary catastrophe that far exceeded the adaptive capabilities of even this remarkably successful group of animals, regardless of their pre-impact status. As research continues, our understanding of dinosaurs’ final chapter will undoubtedly become richer, offering deeper insights into both ancient extinctions and the vulnerability of life to environmental change.