In the late 19th century, a fierce scientific rivalry erupted that would forever change our understanding of prehistoric life and shape the development of American paleontology. This intense competition, known as the “Bone Wars,” pitted two brilliant but deeply flawed paleontologists against each other in a decades-long battle for fossil supremacy. Their ruthless pursuit of dinosaur discoveries led to both groundbreaking scientific advances and shocking ethical breaches that still echo through the scientific community today. The story of the Bone Wars is one of ambition, discovery, deception, and ultimately, an incredible legacy that helped establish dinosaur paleontology as we know it.

The Key Players: Cope and Marsh

At the center of the Bone Wars stood two men: Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh. Cope was a brilliant, self-taught naturalist from a wealthy Quaker family who published his first scientific paper at age 18. Quick-thinking and prolific, he would eventually produce over 1,400 papers during his career. Marsh, meanwhile, came from humble beginnings but had secured a privileged position as the nephew of wealthy philanthropist George Peabody, who funded Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. More methodical than Cope, Marsh became the first professor of paleontology in America at Yale University. The two men initially maintained a cordial relationship, even naming species after each other, but their temperaments and ambitions eventually set them on a collision course that would define both their careers and the future of paleontology.

The Spark That Ignited the Feud

The transformation from colleagues to bitter rivals began in 1868 when Cope invited Marsh to visit a dig site in Haddonfield, New Jersey, where Cope had discovered the first relatively complete dinosaur skeleton in North America, Hadrosaurus. During this seemingly collegiate visit, Marsh secretly bribed the quarry workers to send any new fossil finds directly to him rather than to Cope. When Cope discovered this betrayal, it ignited a smoldering resentment. The final breaking point came in 1869 when Marsh publicly humiliated Cope by pointing out that Cope had mounted the skull of Elasmosaurus (a long-necked marine reptile) on the wrong end of its body, placing it on the tail instead of the neck. This embarrassing error, which Marsh ensured was widely publicized, transformed their relationship into one of outright hostility that would last until Cope died in 1897.

The Western Frontier Battleground

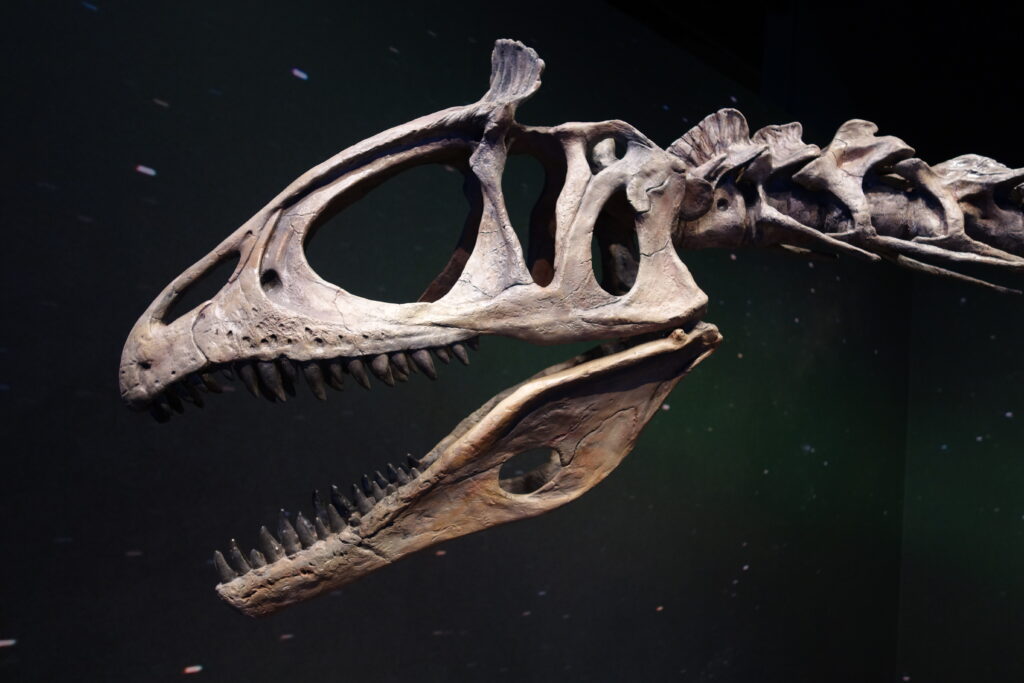

The discovery of rich fossil beds in the American West, particularly in Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana, provided the perfect battleground for Cope and Marsh’s escalating feud. These territories, recently opened by the completion of the transcontinental railroad and the displacement of Native American tribes, contained an unprecedented wealth of prehistoric remains waiting to be discovered. Both paleontologists quickly shifted their operations westward, establishing rival fossil hunting camps that sometimes operated within sight of each other. The rugged western landscapes, from the Morrison Formation to the Hell Creek Formation, yielded spectacular treasures including Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, Diplodocus, and many other iconic dinosaur species. This fossil rush coincided with America’s westward expansion, making the Bone Wars not just a scientific competition but part of the larger narrative of American frontier conquest.

Underhanded Tactics and Sabotage

As their rivalry intensified, both Cope and Marsh resorted to increasingly unethical tactics to undermine each other’s work. Field teams were instructed to destroy fossils they couldn’t collect to prevent them from falling into rival hands, a practice that resulted in the irreversible loss of countless valuable specimens. Bribes were commonplace, with both men paying informants to report on their competitors’ activities and discoveries. They even hired away each other’s fossil collectors, creating a revolving door of employees who carried valuable information between camps. Armed guards were eventually posted at dig sites to prevent espionage and sabotage. Perhaps most egregiously, both men engaged in fossil theft, with Marsh once allegedly having an entire trainload of bones intended for Cope diverted to his institution. These unscrupulous methods reflected just how far the two scientists were willing to go in pursuit of paleontological dominance.

The Rush to Publish

The competitive pressure of the Bone Wars created a frenzied publishing environment that prioritized speed over scientific thoroughness. Both paleontologists rushed preliminary findings into print, often based on fragmentary specimens, to claim naming rights to new species. This haste led to numerous scientific errors and the creation of many “paper dinosaurs”—species named from insufficient evidence that later proved invalid. Cope, particularly prolific, sometimes wrote and submitted papers the same day fossils arrived at his laboratory, barely taking time for proper analysis. Marsh, with greater institutional resources, could sometimes afford more deliberation but still felt constant pressure to publish before Cope claimed priority. The scientific journals of the era were inundated with their competing papers, sometimes publishing contradictory findings in the same issue. This publication race established a problematic precedent that valued quantity over quality in scientific output.

Financial and Personal Costs

The Bone Wars extracted enormous financial and personal tolls from both participants. Cope, who began with significant personal wealth, eventually spent his entire fortune financing expeditions and publications, dying nearly penniless and forced to sell his fossil collection. Marsh, though backed by his wealthy uncle’s endowment and Yale University, nevertheless depleted substantial institutional resources and damaged many professional relationships through his obsessive competition. Both men sacrificed personal relationships, health, and reputation in pursuit of paleontological supremacy. Cope’s marriage suffered tremendously under the financial strain and his frequent absences, while Marsh never married, focusing entirely on his work and rivalry. The stress of the competition likely contributed to Cope’s deteriorating health in his later years. By the time the feud ended with Cope’s death in 1897, both men had paid a devastating price for their scientific ambitions.

Scientific Achievements Despite the Rivalry

Despite the ethical compromises and personal costs, the Bone Wars produced remarkable scientific achievements that transformed our understanding of prehistoric life. Together, Cope and Marsh discovered and described more than 136 new species of dinosaurs, including many iconic forms that remain central to our understanding of the Mesozoic Era. Marsh’s team discovered and named Stegosaurus, Triceratops, Allosaurus, and Diplodocus, while Cope’s discoveries included Camarasaurus, Coelophysis, and Dimetrodon (technically not a dinosaur but a synapsid). Their work established North America as a crucial center for paleontological research, challenging Europe’s previous dominance in the field. The sheer volume of fossils they collected provided the first comprehensive picture of dinosaur diversity and evolution, enabling scientists to begin understanding these creatures as a complex, varied group rather than a handful of isolated specimens. Their discoveries filled museum halls across America, bringing dinosaurs into public consciousness for the first time.

The Birth of American Paleontology

The Bone Wars effectively established paleontology as a major scientific discipline in America. Before Cope and Marsh began their competitive collecting, American museums housed few significant dinosaur specimens, and European institutions dominated the field. The rivalry changed this dynamic dramatically, creating vast fossil collections at Yale’s Peabody Museum and Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences. Their work inspired a generation of new paleontologists who would build upon their discoveries while adopting more methodical and ethical approaches. The Bone Wars also coincided with America’s efforts to establish scientific credibility on the world stage after the Civil War, with dinosaur discoveries becoming a point of national pride. Field methods developed during this period, though often crude by modern standards, laid the groundwork for systematic paleontological excavation. By bringing unprecedented attention and resources to paleontology, Cope and Marsh helped transform it from a gentleman’s hobby into a legitimate scientific profession in America.

Public Fascination and Media Coverage

The bitter rivalry between Cope and Marsh captivated the American public, receiving extensive coverage in newspapers and popular magazines of the day. Publications like the New York Herald devoted front-page stories to their feuding expeditions and spectacular discoveries, introducing millions of Americans to dinosaurs for the first time. The dramatic personal conflict provided a compelling narrative that made paleontology accessible and exciting to ordinary citizens who might otherwise have shown little interest in scientific research. Public lectures featuring dramatic illustrations of newly discovered prehistoric monsters became popular entertainment in major cities. This media attention helped secure both institutional and public funding for paleontological research, as museums competed to display the most impressive dinosaur specimens. The sensationalized coverage of the Bone Wars effectively created the first wave of widespread dinosaur enthusiasm in American culture, establishing a public fascination with prehistoric life that continues to this day.

Errors and Scientific Missteps

The frenetic pace and competitive pressure of the Bone Wars inevitably led to significant scientific errors that would take decades to correct. Both men frequently named new species based on frustratingly incomplete material, sometimes from just a few bones. This haste resulted in numerous duplicate namings, taxonomic confusion, and “wastebasket taxa” where unrelated fossils were incorrectly grouped. Marsh once famously created the non-existent dinosaur “Apatosaurus” by mistakenly giving different names to juvenile and adult specimens of the same species (though Apatosaurus was eventually proven valid while Brontosaurus was temporarily invalidated). Cope’s infamous Elasmosaurus blunder, mounting the skull on the wrong end, exemplified how even brilliant scientists could make elementary mistakes when rushing their work. The cleanup of this taxonomic mess occupied later generations of paleontologists, who had to meticulously reexamine specimens and publications to sort fact from fiction. Some controversies stemming from Cope and Marsh’s hasty identifications remain unresolved more than a century later.

Ethical Legacy and Scientific Reform

The excesses of the Bone Wars eventually prompted important ethical reforms in paleontological practice. The destruction of fossils, claim-jumping, and sabotage that characterized the Cope-Marsh rivalry became cautionary tales for future scientists. Professional societies formed in the early 20th century established codes of conduct that explicitly prohibited many of the tactics employed during the Bone Wars. Modern paleontological expeditions now emphasize meticulous documentation, careful extraction, and proper preservation of contextual information that was often ignored in the rush to collect specimens during the 1870s and 1880s. The scientific community also developed more rigorous peer review standards for publishing new fossil discoveries, requiring substantially more evidence than was typical during the Bone Wars. Perhaps most importantly, collaborative research gradually replaced the intensely competitive model exemplified by Cope and Marsh, with institutions sharing resources and information rather than hoarding discoveries. These ethical reforms represent an important, if belated, recognition of the damage caused by unchecked scientific rivalry.

The Final Years and Aftermath

By the 1890s, the Bone Wars were winding down as both financial resources and new fossil sites became scarcer. Cope’s finances were in ruins, forcing him to sell his massive fossil collection and take up residence in a small room at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. In a final bizarre twist to their rivalry, Cope donated his body to science with the strange stipulation that his skull be preserved and submitted as a candidate for measurement in a study of brain size among eminent scientists—a direct challenge to Marsh, whose cranial capacity he believed would prove inferior to his own. Marsh died in 1899, just two years after Cope, having maintained his Yale position but with his reputation somewhat diminished by the public exposure of their feud’s uglier aspects. The immediate aftermath saw a generation of paleontologists working to integrate and correct the chaotic body of research the two rivals had produced. Museums spent decades sorting through, mounting, and properly identifying the thousands of specimens collected during the Bone Wars, a process that continues even today.

Why the Bone Wars Still Matter Today

The legacy of the Bone Wars extends far beyond the 19th century, continuing to influence paleontology and science more broadly. Modern discussions about scientific ethics regularly reference the Cope-Marsh feud as a landmark case study in how competition can both drive and damage scientific progress. The vast collections amassed during the Bone Wars remain vital research resources, with new technologies like CT scanning and biochemical analysis revealing fresh insights from specimens collected over 140 years ago. Taxonomic revisions of Cope and Marsh’s work continue, with the 2015 reinstatement of Brontosaurus as a valid genus (after being previously synonymized with Apatosaurus) demonstrating how their discoveries remain scientifically relevant. The sensationalized media coverage that surrounded their rivalry established a template for public communication about paleontology that persists in documentaries and museum exhibits today. Perhaps most significantly, the Bone Wars represent a pivotal moment when dinosaurs entered the American imagination, beginning their transformation from obscure scientific curiosities into cultural icons that continue to captivate our collective imagination.

The Lasting Impact of the Bone Wars on Science and Paleontology

The Bone Wars stand as one of the most fascinating chapters in the history of science—a tale of brilliant discovery marred by personal animosity and ethical compromise. While Cope and Marsh’s ruthless competition drove remarkable advances in our understanding of prehistoric life, their story serves as both inspiration and warning to modern scientists. Their legacy lives on in museum halls across America, where visitors still marvel at the spectacular creatures these feuding paleontologists introduced to the world. The dinosaurs they discovered continue to educate and fascinate new generations, even as we recognize the flawed and human story behind their unearthing. In many ways, modern paleontology has defined itself both in continuation of their pioneering work and deliberate contrast to their methods, building on their discoveries while striving to avoid repeating their mistakes.