When we envision the Mesozoic Era—the Age of Dinosaurs spanning from 252 to 66 million years ago—our minds often conjure images of towering sauropods and fearsome predators like Tyrannosaurus rex stalking the prehistoric landscapes. However, equally fascinating and perhaps even more terrifying were the ancient marine ecosystems teeming with predators that would make today’s sharks seem almost harmless by comparison. The waters of the Mesozoic harbored an astonishing array of reptiles, fish, and invertebrates that evolved remarkable adaptations for life in prehistoric seas. From bus-sized marine reptiles with powerful jaws to armored fish and giant arthropods, these creatures dominated aquatic environments while dinosaurs ruled on land. This exploration into the depths of prehistoric oceans reveals a world both alien and fascinating, where apex predators lurked beneath the waves and bizarre lifeforms thrived in marine habitats that no longer exist.

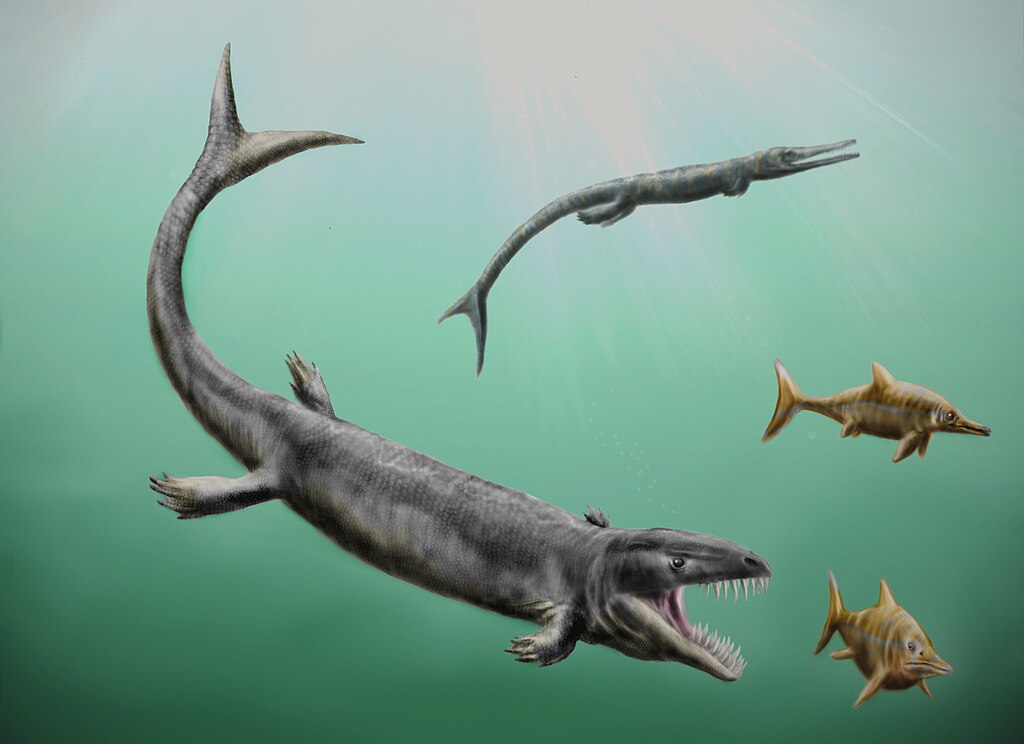

Mosasaurs: The Sea’s Ultimate Predators

Among the most formidable hunters in Mesozoic seas were the mosasaurs, massive marine reptiles that evolved from lizards and came to dominate late Cretaceous oceans worldwide. These creatures could reach astonishing proportions, with species like Mosasaurus hoffmanni growing up to 17 meters (56 feet) in length—about the size of a school bus. Mosasaurs possessed double-hinged jaws similar to those of snakes, allowing them to swallow large prey whole while their mouths were lined with multiple rows of razor-sharp teeth. Fossil evidence reveals that mosasaurs were apex predators with diverse diets, feeding on fish, ammonites, sea birds, and even other marine reptiles. Their powerful paddle-like limbs and long, flexible bodies made them swift and agile hunters capable of explosive bursts of speed. By the end of the Cretaceous Period, mosasaurs had diversified into numerous species occupying various ecological niches, from shallow coastal waters to the open ocean.

Plesiosaurs: Long-Necked Enigmas

Perhaps the most distinctive marine reptiles of the Mesozoic were the plesiosaurs, characterized by their remarkably long necks, compact bodies, and four powerful flipper-like limbs. These creatures first appeared in the late Triassic Period and persisted until the end-Cretaceous extinction event, evolving into two main body types with different hunting strategies. The “true” plesiosaurs possessed extremely elongated necks containing up to 76 vertebrae—the longest necks of any known vertebrate—which they likely used to sneak up on prey in murky waters or reach into crevices. Contrary to popular depictions, research suggests these necks were not highly flexible in a vertical plane, meaning plesiosaurs couldn’t raise their heads high above the water in a swan-like fashion. Plesiosaurs propelled themselves using a unique four-flipper swimming method, generating thrust by “flying” through the water much like penguins do today. Their diet likely consisted primarily of fish and cephalopods, which they would capture with their needle-like teeth designed for trapping rather than tearing prey.

Pliosaurs: Short-Necked Monsters

While their plesiosaur cousins evolved long necks, pliosaurs developed a dramatically different body plan that made them among the most terrifying predators ever to swim Earth’s oceans. These short-necked plesiosaurs evolved massive heads powered by enormous jaw muscles, with some specimens possessing skulls over 2 meters (6.5 feet) long equipped with conical teeth measuring up to 30 centimeters (12 inches). The largest known pliosaur, Pliosaurus funkei (informally called “Predator X”), may have reached lengths of 13 meters (43 feet) with an estimated bite force exceeding that of Tyrannosaurus rex. These marine reptiles possessed four powerful flippers that could span up to 2 meters each, allowing them to accelerate rapidly and overtake prey with bursts of incredible speed. Fossil evidence shows that pliosaurs were hypercarnivorous apex predators capable of attacking and consuming anything in their environment, including other marine reptiles close to their size. Their powerful jaws and teeth were adapted for delivering devastating crushing bites, enabling them to dismember large prey before consumption.

Ichthyosaurs: Dolphin-Like Marine Reptiles

Among the most perfectly adapted marine reptiles were the ichthyosaurs, whose streamlined, dolphin-like bodies represent one of nature’s most remarkable examples of convergent evolution. Despite having no direct relation to modern marine mammals, ichthyosaurs independently evolved strikingly similar body shapes optimized for fast swimming, including a dorsal fin, crescent-shaped tail fluke, and smooth hydrodynamic profile. These reptiles first appeared in the early Triassic, shortly after the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event, and quickly diversified to become dominant ocean predators. Unlike other marine reptiles, ichthyosaurs gave birth to live young in the water rather than returning to land to lay eggs, as evidenced by remarkable fossils showing embryos inside maternal bodies or even caught in the process of being born. Advanced adaptations in ichthyosaur eyes included large orbits and bony rings (sclerotic rings) that helped maintain eye shape under pressure, suggesting some species could dive to extreme depths in pursuit of prey. Certain ichthyosaur species like Temnodontosaurus and Shonisaurus reached massive sizes comparable to modern whales, with the largest specimens measuring up to 21 meters (70 feet) in length.

Prehistoric Sharks: Ancient Cartilaginous Predators

While reptiles dominated many Mesozoic marine ecosystems, sharks had already been thriving in Earth’s oceans for over 200 million years before dinosaurs evolved, developing diverse forms during the Mesozoic Era. Among the most unusual was Helicoprion, which possessed a bizarre spiral arrangement of lower teeth resembling a circular saw that continuously rotated forward as new teeth developed. The Jurassic Period saw the evolution of more recognizably modern shark forms, including the massive Hybodus with its distinctive dorsal fin spines and multi-purpose dentition that allowed it to feed on both hard-shelled prey and fish. By the Cretaceous Period, lamniform sharks similar to modern great whites and makos had become established, including Cretoxyrhina (the “Ginsu shark”), which grew to about 7 meters (23 feet) long and possessed powerful slicing teeth ideal for hunting marine reptiles. Unlike their marine reptile contemporaries, sharks survived the end-Cretaceous extinction event, allowing their evolutionary lineage to continue developing into the approximately 500 shark species that patrol today’s oceans.

Ammonites: Shelled Cephalopod Masters

The Mesozoic seas teemed with ammonites, shelled cephalopods related to modern squids and octopuses that became extraordinarily abundant and diverse throughout the era. These creatures possessed coiled shells divided into chambers connected by a siphuncle tube, which allowed them to control their buoyancy by regulating gas and fluid within the chambers. Ammonite shells ranged dramatically in size from species smaller than a coin to giants like Parapuzosia seppenradensis, which grew shells nearly 2 meters (6.5 feet) in diameter. The animals themselves occupied only the outermost chamber of their shells, extending tentacles to capture prey while using a powerful beak to tear food into manageable pieces. Ammonites were so abundant and evolved so quickly that their fossilized shells serve as important index fossils, helping geologists date rock layers and track evolutionary changes across the Mesozoic. Despite surviving multiple extinction events and diversifying into an estimated 10,000 species throughout their 350-million-year history, ammonites finally disappeared during the same catastrophic event that eliminated non-avian dinosaurs, leaving nautiluses as the only externally-shelled cephalopods to survive into the modern era.

Giant Sea Turtles: Ancient Mariners

Among the largest reptiles plying Cretaceous seas were giant marine turtles that dwarfed even today’s leatherbacks, the largest living turtles. The most spectacular of these prehistoric mariners was Archelon, which lived approximately 75 million years ago in the Western Interior Seaway that divided North America. This enormous turtle reached lengths of up to 4.6 meters (15 feet) from head to tail and possessed a flipper span approaching 5 meters (16 feet). Unlike modern sea turtles with solid shells, Archelon had a reduced, leather-like carapace supported by a framework of thickened ribs, possibly an adaptation that decreased weight while maintaining some protection. Fossil evidence suggests these behemoths fed primarily on slow-moving prey like ammonites, using their powerful beaks to crush mollusk shells and extract the nutritious flesh within. These giant turtles likely faced predation from large marine reptiles, particularly mosasaurs, which would have been among the few creatures capable of attacking such massive, well-defended animals. Despite their impressive size and adaptations, these giant sea turtles disappeared at the end of the Cretaceous, with modern sea turtles evolving from different, smaller turtle lineages that somehow survived the mass extinction.

Crocodilians: Marine Adaptations

Today’s crocodiles and alligators are primarily freshwater ambush predators, but during the Mesozoic Era, diverse crocodyliform species took to the seas with remarkable adaptations for marine life. Perhaps the most specialized were the thalattosuchians, which evolved paddle-shaped limbs, tail flukes, and streamlined bodies reminiscent of dolphins and ichthyosaurs. Dakosaurus, nicknamed the “Godzilla crocodile,” combined these aquatic adaptations with a short, bulldog-like snout filled with serrated, ziphodont teeth similar to those of terrestrial predatory dinosaurs—a specialized dentition for slicing through flesh rather than gripping prey. In contrast, the long-snouted teleosaurids retained more typical crocodilian features while still adapting to marine environments, likely hunting fish in shallow coastal waters using their elongated jaws lined with numerous interlocking teeth. Some marine crocodyliform species grew to impressive sizes, with Machimosaurus rex reaching estimated lengths of 9.6 meters (31 feet), making it one of the largest crocodyliform reptiles ever to exist. Unlike many other Mesozoic marine reptiles, crocodilians as a group survived the end-Cretaceous extinction event, though the highly specialized marine forms disappeared, leaving primarily freshwater and brackish-water species to carry the evolutionary lineage forward.

Xiphactinus: The Bulldog of the Cretaceous Seas

Not all fearsome Mesozoic marine predators were reptiles—the Late Cretaceous oceans were also patrolled by massive predatory fish that would dwarf many modern species. Among the most formidable was Xiphactinus, a giant teleost fish that grew up to 6 meters (20 feet) long with a bulldog-like face featuring a protruding lower jaw lined with large, fang-like teeth. This massive predator is known from particularly spectacular fossils, including the famous “Fish-Within-A-Fish” specimen displayed at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History, which contains a perfectly preserved 2-meter (6-foot) fish called Gillicus inside Xiphactinus’s body cavity. This remarkable fossil captures the predator’s last meal—evidence suggesting that Xiphactinus may have died from injuries sustained while swallowing the surprisingly large prey whole or from the prey fish’s body rupturing its internal organs. Xiphactinus belonged to the extinct family Ichthyodectidae and was related to modern tarpon and ladyfish, though vastly exceeding them in size and predatory capabilities. Despite its fearsome appearance and position as a top predator in the Western Interior Seaway that covered much of central North America, Xiphactinus went extinct alongside many other marine creatures at the end of the Cretaceous Period.

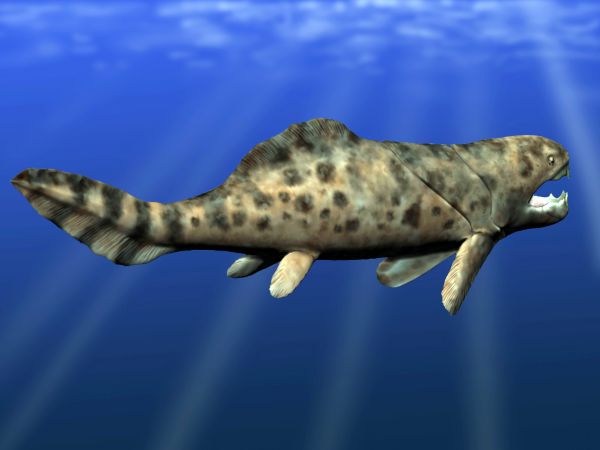

Dunkleosteus: The Armored Terror

While slightly predating the Mesozoic Era, no discussion of prehistoric marine predators would be complete without mentioning Dunkleosteus, perhaps the most terrifying fish ever to swim Earth’s oceans. This massive armored fish from the Late Devonian Period (approximately 358-382 million years ago) belonged to a group called placoderms, characterized by bony plates forming a shield-like covering over their heads and thoraxes. Instead of teeth, Dunkleosteus possessed self-sharpening bony plates that formed blade-like structures capable of snapping shut with tremendous force, estimated at over 7,400 newtons (1,660 lbf) at the tip of the jaws. These specialized cutting structures allowed it to slice through virtually anything in its path, including the armored bodies of other placoderms and early sharks. The largest species, Dunkleosteus terrelli, reached lengths of up to 6 meters (20 feet) and weighed approximately 1 ton, making it among the largest predatory fish ever to exist. Despite their fearsome adaptations and position as apex predators, placoderms mysteriously disappeared during the Late Devonian extinction event, leaving their ecological niches to be filled by sharks and other fish groups that would eventually dominate Mesozoic seas.

Marine Reptile Diversity Beyond the Giants

While mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and ichthyosaurs tend to dominate discussions of Mesozoic marine life, these waters harbored numerous other reptile groups that evolved adaptations for aquatic living. Among the most specialized were the thalattosaurs, “sea lizards” from the Triassic Period with elongated, sometimes downturned snouts likely used for probing seafloor sediments for invertebrate prey. Placodonts, another Triassic marine group, evolved flat, shell-crushing teeth perfectly suited for feeding on hard-shelled mollusks, with some species even developing turtle-like armor for protection. The hupehsuchians represented another successful experiment in marine adaptation, developing wide, stiffened bodies with both limb-based propulsion and vertical tail flukes. Several groups of nothosaurs occupied intermediate ecological niches between fully aquatic and semi-aquatic lifestyles, representing transitional forms in the evolution toward plesiosaurs. Even some pterosaurs adapted partially to marine environments, with species like Pteranodon developing specialized lifestyles for snatching fish from the ocean surfaces during gliding flights over ancient seas. This remarkable diversity of marine reptiles demonstrates the evolutionary flexibility of reptilian anatomy, allowing multiple lineages to independently adapt to aquatic niches throughout the Mesozoic Era.

Life in Ancient Coral Reefs

Beneath the waves where giant marine reptiles hunted, Mesozoic coral reefs created complex ecosystems supporting extraordinary biodiversity, much as they do today. Triassic and early Jurassic reefs were dominated by scleractinian corals similar to modern species, which began their evolutionary rise after the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction eliminated the rugose and tabulate corals that had previously dominated marine ecosystems. These ancient reefs provided critical habitat for countless invertebrate species, including bizarre rudist bivalves that evolved a coral-like lifestyle, with some species growing conical shells up to a meter tall that formed reef-like structures in warm, shallow Cretaceous seas. Mesozoic reefs teemed with echinoids (sea urchins and sand dollars) that underwent significant evolutionary radiation, producing numerous specialized forms adapted to different microhabitats within reef ecosystems. Fossil evidence shows that many modern fish families had already established themselves in and around these reefs, including early representatives of familiar groups like wrasses, triggerfishes, and angelfishes, which evolved specialized feeding adaptations to exploit reef resources. The dynamic reef communities supported complex food webs that ultimately provided prey for the larger pelagic predators, creating interconnected marine ecosystems remarkably similar in structure, if not in specific components, to those found in today’s oceans.