When we think of dinosaurs today, we might conjure images of towering T. rexes or long-necked Brachiosaurus. However, dinosaur discovery began centuries ago with a much less celebrated creature. The first scientifically documented dinosaur fossil sparked a revolution in our understanding of Earth’s history and laid the groundwork for paleontology as we know it today. This fascinating story of discovery involves curious natural philosophers, misidentifications, and the gradual unveiling of creatures that had been hidden in stone for millions of years. Let’s explore the identity of the first officially recognized dinosaur and the remarkable journey that began humanity’s fascination with these prehistoric giants.

Megalosaurus: The First Named Dinosaur

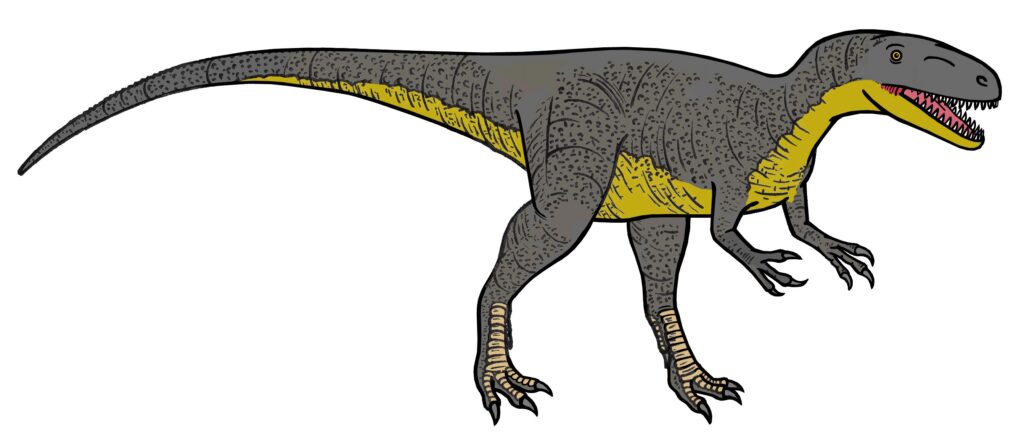

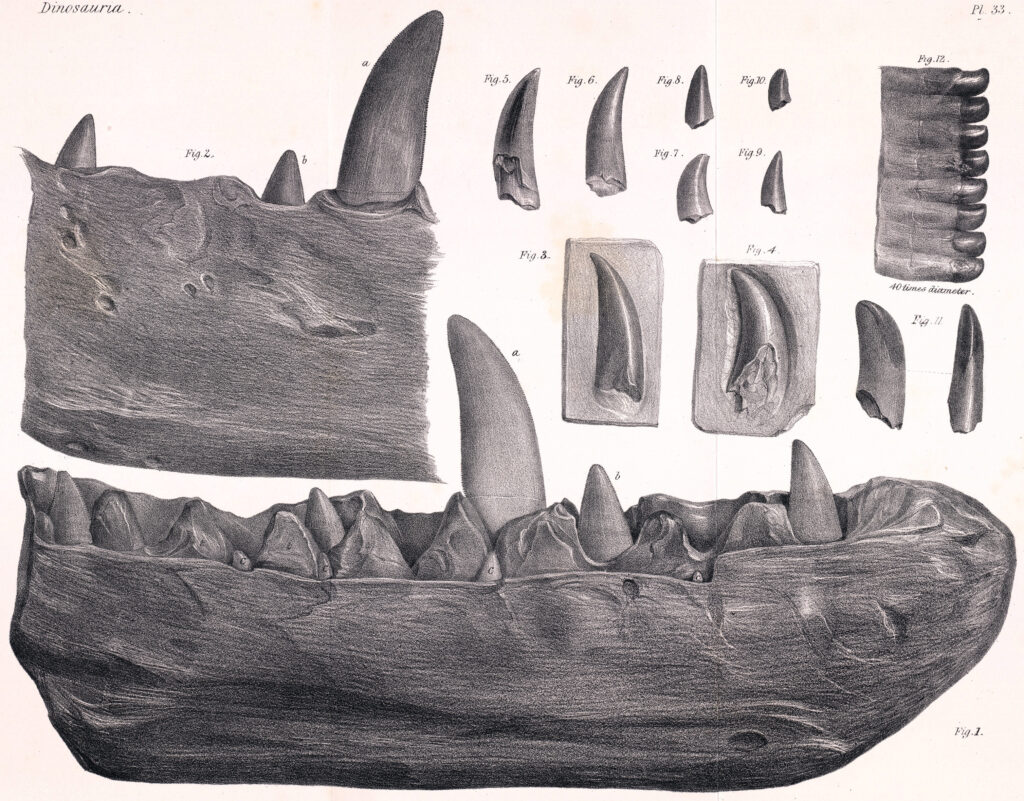

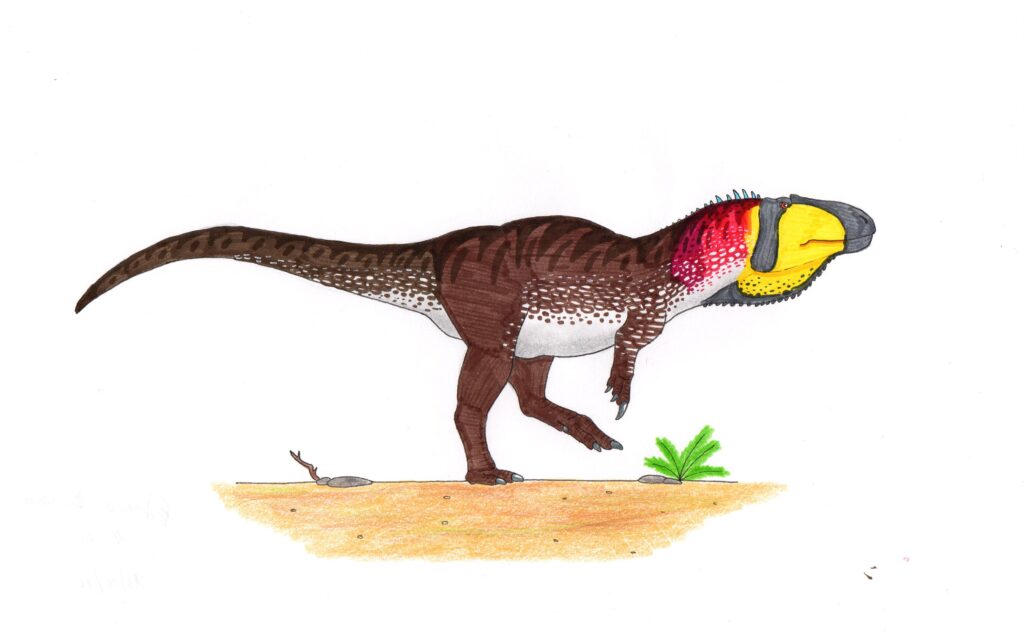

Megalosaurus has the distinction of being the first dinosaur to receive a formal scientific name and description in scientific literature. In 1824, Oxford geologist William Buckland published a paper describing unusually large fossil bones found in Jurassic limestone formations near Oxford, England. He named this creature “Megalosaurus,” meaning “great lizard,” and classified it as an enormous extinct reptile. The material Buckland worked with included a lower jawbone with teeth, vertebrae, and limb bones. Though Buckland didn’t yet have the concept of “dinosaurs” to work with, his description of Megalosaurus marks the first scientific documentation of what we now recognize as a dinosaur species. This theropod dinosaur lived during the Middle Jurassic period, approximately 168 to 166 million years ago, and is estimated to have reached lengths of around 30 feet.

Earlier Unrecognized Discoveries

While Megalosaurus represents the first scientifically named dinosaur, fossil evidence suggests humans had been encountering dinosaur remains for centuries or even millennia before this formal recognition. Ancient Chinese documents describe “dragon bones” that were likely dinosaur fossils. In Europe, historians believe that some mythological creatures may have been inspired by fossilized dinosaur remains discovered by early peoples. In the 17th century, British naturalist Robert Plot illustrated a large thigh bone in his Natural History of Oxfordshire (1677), which we now know was likely from a Megalosaurus, though he misidentified it as belonging to a giant human. Similarly, a piece of a Megalosaurus jaw was illustrated in 1763 by Richard Brookes, who labeled it “Scrotum humanum” due to its resemblance to human anatomy. These early encounters with dinosaur fossils demonstrate that humans had been finding these remains long before understanding what they truly represented.

The Coinage of “Dinosauria”

The term “dinosaur” itself wasn’t coined until 1842, years after the first dinosaur species had been scientifically described. British anatomist Sir Richard Owen examined fossils of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus and recognized that these creatures formed a distinct group of reptiles unlike any living ones today. He named this group “Dinosauria,” meaning “terrible lizards,” during a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Owen’s recognition united these seemingly disparate creatures under a common classification, representing a pivotal moment in paleontological history. This taxonomic designation helped formalize the study of dinosaurs as a scientific field and provided a framework for understanding subsequent fossil discoveries. Owen’s contribution transformed how scientists approached these prehistoric creatures, shifting from viewing them as curiosities to seeing them as a unique and important group of extinct animals with evolutionary significance.

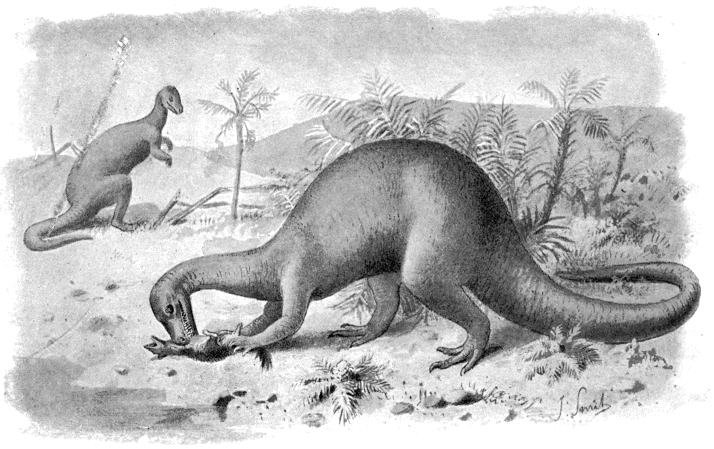

Iguanodon: The Second Dinosaur Discovery

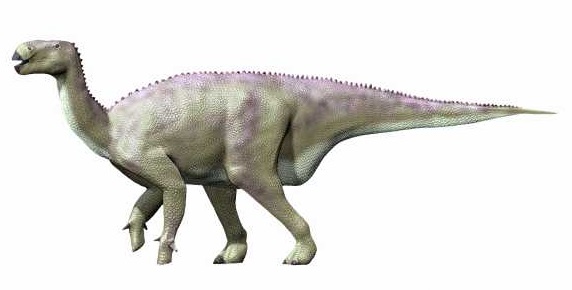

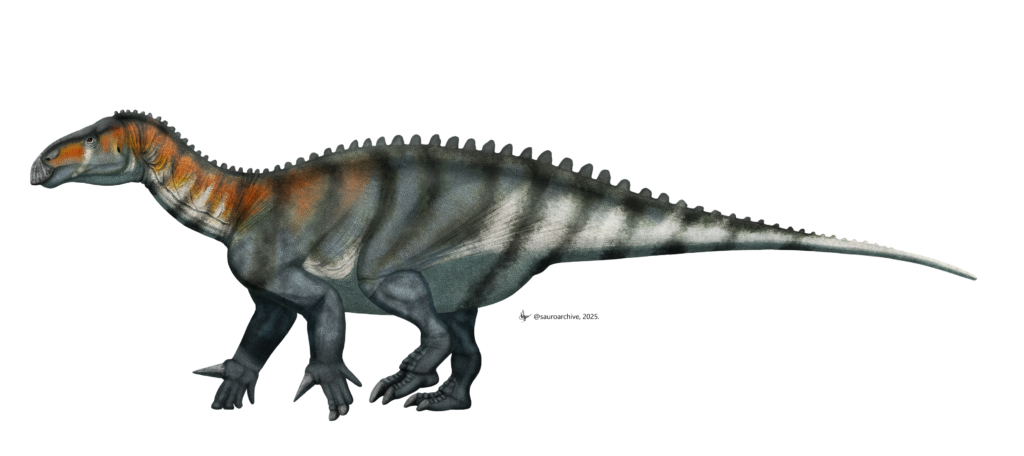

Following closely on the heels of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon became the second dinosaur to receive scientific recognition. In 1822, Mary Ann Mantell, wife of British physician and geologist Gideon Mantell, reportedly discovered large fossilized teeth while walking along a Sussex road. Upon examining these unusual teeth, Gideon Mantell noticed similarities to those of modern iguanas, albeit much larger, leading him to name the creature “Iguanodon” or “iguana tooth” when formally describing it in 1825. Unlike the carnivorous Megalosaurus, Iguanodon was a herbivore and one of the first plant-eating dinosaurs identified by science. Its distinctive thumb spike, initially misinterpreted as a horn on its nose in early reconstructions, became one of the most recognizable features of this iconic dinosaur. The discovery of Iguanodon helped broaden the scientific understanding of dinosaur diversity beyond just predatory species.

The Role of the Industrial Revolution

The timing of the first dinosaur discoveries was not coincidental but rather closely tied to the Industrial Revolution sweeping through Europe. The expansion of mining, quarrying, canal construction, and railway building during the late 18th and early 19th centuries led to unprecedented excavation of the Earth’s layers. These industrial activities exposed fossil-bearing rocks that had remained hidden for millions of years, bringing dinosaur remains to light at an accelerating rate. Workers in mines and quarries frequently encountered strange bones and brought them to the attention of local physicians or natural philosophers. The construction of the British railway system proved particularly fruitful for fossil discoveries, with numerous important specimens uncovered while cutting through hillsides for rail lines. This intersection of industrial development and scientific discovery highlights how technological progress unexpectedly contributed to advancing our understanding of Earth’s distant past.

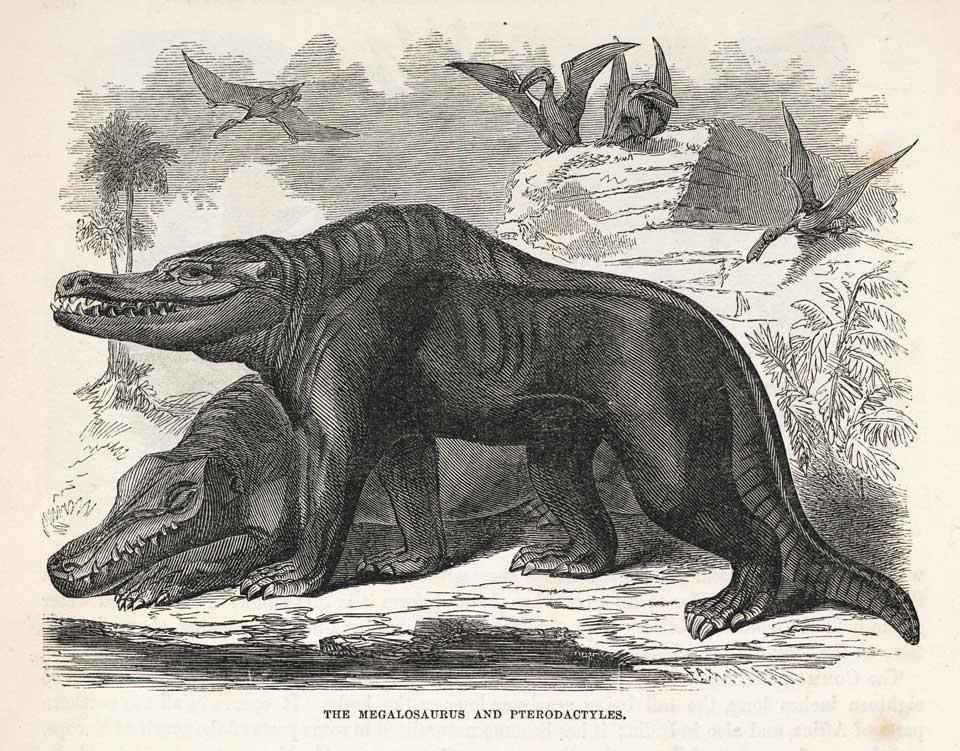

The Hawkins Sculptures: Bringing the First Dinosaurs to Life

The first attempt to visualize dinosaurs for the public occurred in the 1850s through a remarkable collaboration between sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and Richard Owen. For the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1854, Hawkins created life-sized concrete models of several dinosaurs, including Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, based on Owen’s scientific guidance. These sculptures, still standing today in London’s Crystal Palace Park, represent the world’s first dinosaur reconstructions and offered Victorian society its first glimpse of how these ancient creatures might have appeared. Though highly inaccurate by modern standards—depicting Megalosaurus as a bulky quadrupedal beast rather than the bipedal predator we now know it was—these sculptures caused a sensation and sparked public fascination with prehistoric life. The famous New Year’s Eve dinner party held inside the unfinished Iguanodon model in 1853, where scientists and dignitaries dined within the creature’s concrete ribcage, symbolized the entrance of dinosaurs into popular culture and the public imagination.

Scientific Context of the First Discovery

The first dinosaur discovery occurred during a period of significant transition in scientific thinking about Earth’s history. When Buckland described Megalosaurus in 1824, most naturalists still adhered to catastrophism—the theory that Earth had been shaped by a series of catastrophic events, often aligned with biblical accounts like the Great Flood. The emerging evidence of extinct creatures challenged this worldview, suggesting Earth had a much longer and more complex history than previously believed. Geologist Charles Lyell was developing his principles of uniformitarianism, proposing that the same geological processes observable today had shaped Earth over vast periods. Against this intellectual backdrop, dinosaur discoveries provided compelling evidence for an ancient Earth populated by creatures no longer existing. The recognition of dinosaurs ultimately contributed to the scientific revolution that transformed our understanding of planetary and biological history, paving the way for evolutionary theory and modern geology.

Misinterpretations of Early Dinosaur Fossils

The first dinosaur discoveries were fraught with misinterpretations that reflect the limited framework early naturalists had for understanding such unusual remains. Before the concept of dinosaurs existed, fossil bones were often attributed to biblical giants, dragons, or exceptionally large modern animals. When Reverend Plot discovered what was likely a Megalosaurus femur in the 1600s, he suggested it belonged to a war elephant brought to Britain by the Romans or possibly a giant human mentioned in scripture. Even after Buckland’s formal description of Megalosaurus, early reconstructions depicted it as a gigantic, lizard-like quadruped rather than the bipedal predator we now understand it to be. Similarly, Mantell’s initial reconstruction of Iguanodon placed a horn-like spike on its nose when this was a modified thumb that the animal used for defense or gathering food. These misinterpretations demonstrate how scientific understanding progresses through successive refinements as more evidence emerges and conceptual frameworks evolve to accommodate discoveries.

The Fossil Hunters: Key Figures in Early Dinosaur Discovery

Beyond Buckland and Mantell, several other remarkable individuals played crucial roles in early dinosaur paleontology. Mary Anning, though primarily known for her marine reptile discoveries along the Dorset coast, contributed significantly to the emerging understanding of prehistoric life that contextualizes dinosaur discoveries. Her meticulous work with plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs helped establish rigorous methods for fossil extraction and interpretation. Geologist William Smith’s pioneering work on stratigraphy—identifying how rock layers correlate with specific periods—provided the crucial framework for dating dinosaur fossils. Anatomist Georges Cuvier, while never working directly with dinosaur material, developed comparative anatomy techniques essential for interpreting fossil bones and established the reality of extinction as a biological phenomenon. The wealthy fossil collector Thomas Hawkins acquired numerous specimens that advanced scientific knowledge, though his tendency to “enhance” fossils with fictional elements sometimes complicated scientific interpretation. These diverse contributors, each bringing different skills and perspectives, collectively established the foundations of dinosaur paleontology as a scientific discipline.

America’s First Dinosaur Discoveries

While Europe witnessed the first formal dinosaur descriptions, North America soon followed with significant discoveries of its own. In 1858, the first substantially complete dinosaur skeleton was found in Haddonfield, New Jersey, by William Parker Foulke. Named Hadrosaurus foulkii by paleontologist Joseph Leidy, this discovery was revolutionary because it provided definitive evidence that some dinosaurs were bipedal, walking on two legs rather than four. This fundamentally changed the scientific understanding of dinosaur posture and locomotion. Earlier American discoveries included isolated teeth found in Montana that were incorrectly attributed to mammals. By the 1870s, the “Bone Wars” erupted between rival paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, resulting in a competitive fossil-hunting frenzy that dramatically expanded the catalog of known dinosaur species. This notorious scientific feud, despite its personal animosity and ethical lapses, accelerated American dinosaur discovery and brought dozens of new species to scientific attention, including iconic dinosaurs like Triceratops, Stegosaurus, and Allosaurus.

The Cultural Impact of the First Dinosaur Discoveries

The discovery of Megalosaurus and subsequent dinosaurs profoundly impacted Victorian society and culture, extending far beyond scientific circles. These revelations about Earth’s mysterious past captivated the public imagination during a period already fascinated with natural history and geological discoveries. The Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures became a tourist attraction, drawing crowds eager to glimpse representations of these prehistoric beasts. Literature reflected this dinosaur fascination, most notably in Charles Dickens’ opening to “Bleak House” with its memorable description of a metaphorical Megalosaurus “waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.” Educational materials began featuring dinosaurs, introducing generations of schoolchildren to paleontology. Religious thinkers grappled with the theological implications of extinct creatures that existed long before human biblical history. These cultural reverberations demonstrate how dinosaur discoveries did more than advance science—they transformed how people conceptualized Earth’s history and humanity’s place within it, creating a fascination with prehistoric life that continues unabated today.

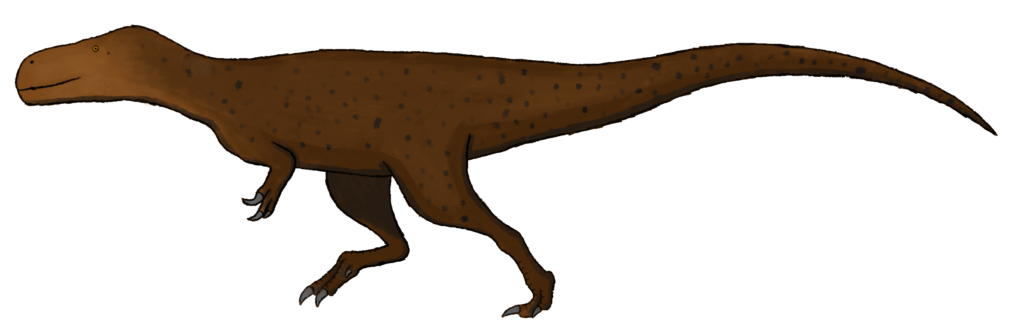

Modern Reassessments of Megalosaurus

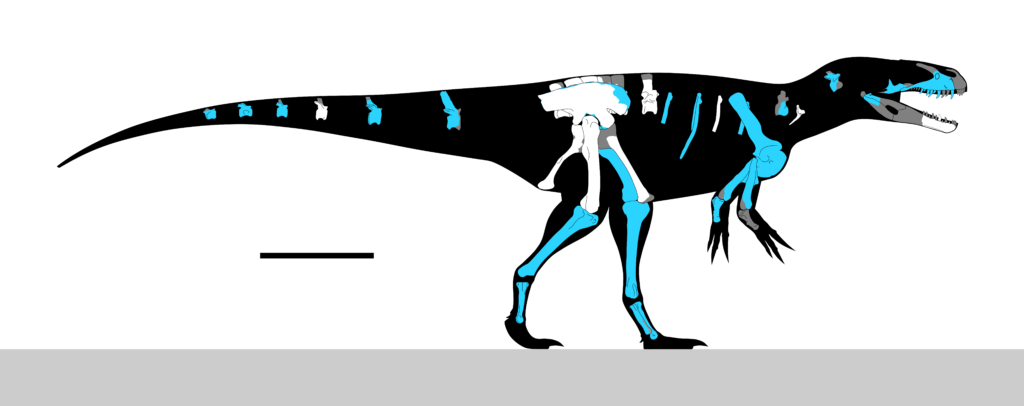

Our understanding of Megalosaurus has evolved dramatically since its first description almost two centuries ago. Modern paleontologists recognize Megalosaurus as a large theropod dinosaur belonging to the megalosaurid family, a group of carnivorous dinosaurs that flourished during the Middle to Late Jurassic period. Unlike early depictions as a quadrupedal, lizard-like creature, we now know Megalosaurus stood on powerful hind legs with smaller forelimbs, similar in general body plan to its more famous later relative, Allosaurus. The fragmentary nature of original Megalosaurus fossils has made comprehensive reconstruction challenging, with the holotype specimen consisting primarily of a partial jawbone. New fossil discoveries throughout England have gradually improved our understanding, though Megalosaurus remains less completely known than many later dinosaur discoveries. Advances in comparative anatomy, biomechanics, and evolutionary biology have allowed paleontologists to place Megalosaurus within a more precise evolutionary context, recognizing it as an important representative of early large theropod evolution rather than the anomalous monster it appeared to be when first discovered.

The Legacy of the First Dinosaur Discovery

The identification of Megalosaurus as the first scientifically described dinosaur marked the beginning of a journey of discovery that continues to this day. This initial finding established methodologies for describing, naming, and classifying extinct animals that would guide generations of paleontologists in their work. The early misconceptions about dinosaur anatomy and biology serve as important reminders of how scientific understanding progresses through constant refinement and revision as new evidence emerges. Each year, approximately 50 new dinosaur species are named, building upon the foundation laid by Buckland’s original Megalosaurus description. Modern paleontological techniques now include sophisticated CT scanning, biomechanical modeling, soft tissue analysis, and molecular studies unimaginable to early dinosaur researchers. The journey from Megalosaurus to our current understanding of dinosaur diversity, representing over 1,000 scientifically named species, illustrates one of science’s greatest success stories—the reconstruction of a lost world through careful observation, analysis, and interpretation of fossil evidence. The first dinosaur discovery opened a window into Earth’s distant past that continues to widen with each new finding.

The Discovery of Megalosaurus: Unveiling Earth’s Prehistoric Past

From Megalosaurus’s first scientific description to today’s sophisticated understanding of dinosaur evolution, behavior, and biology, the story of dinosaur discovery represents one of science’s most fascinating journeys. What began with curious bone fragments in English quarries has expanded into a global enterprise, uncovering the rich diversity of life that dominated terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years. That first dinosaur discovery forever changed our perception of Earth’s history, revealing a planet that had been home to extraordinary creatures long before human existence. As paleontologists continue to unearth new specimens and develop innovative techniques for studying them, the legacy of that first Megalosaurus discovery lives on—reminding us that even the most established scientific understanding remains open to revision as we continue learning about our planet’s remarkable prehistoric past.