For decades, our perception of dinosaurs was shaped by artwork that portrayed them as sluggish, scaly creatures dragging their tails along the ground. These images became deeply embedded in the public consciousness through museum displays, books, films, and toys. However, paleontological discoveries over the past forty years have dramatically transformed our understanding of how dinosaurs looked and behaved. The gap between these artistic representations and scientific reality represents one of the most significant disconnects between popular culture and science in modern times. This article explores how artistic interpretations influenced generations of dinosaur enthusiasts, why these depictions persisted despite evolving evidence, and how our visual understanding of these prehistoric creatures has been revolutionized.

The Victorian Genesis of Dinosaur Imagery

The earliest influential dinosaur reconstructions emerged in Victorian England, particularly through the work of paleoartist Waterhouse Hawkins and scientist Richard Owen. Their Crystal Palace dinosaurs, unveiled in 1854, established the first public vision of what dinosaurs might have looked like. These statues depicted creatures like Iguanodon as heavy, quadrupedal reptiles resembling rhinoceros-lizard hybrids. Though revolutionary for their time, these representations were created when only fragmentary fossils were available, forcing artists to fill enormous gaps with conjecture. The reptilian appearance seemed logical since dinosaurs were classified within Reptilia, prompting artists to use modern lizards and crocodiles as reference points. These Victorian interpretations cast a long shadow, establishing a visual template that would influence dinosaur art for over a century.

Charles R. Knight and the American Dinosaur Renaissance

In the early 20th century, American artist Charles R. Knight became perhaps the most influential paleoartist in history, creating iconic murals for major natural history museums across the United States. Knight’s dinosaurs, while more dynamic than Victorian interpretations, still portrayed them as essentially reptilian in appearance and behavior. His famous paintings of Tyrannosaurus confronting Triceratops and herds of Brontosaurus (now Apatosaurus) in swampy landscapes became definitive images for generations of Americans. Knight worked closely with paleontologists like Henry Fairfield Osborn, incorporating the latest scientific theories, yet his dinosaurs maintained distinctly lizard-like qualities. The artistic techniques he pioneered—dramatic lighting, environmental context, and behavioral interactions—established the visual language for dinosaur art that would dominate until the 1970s.

Rudolph Zallinger and the “Age of Reptiles” Mural

Perhaps no single artwork shaped public perception of dinosaurs more powerfully than Rudolph Zallinger’s monumental “Age of Reptiles” mural at Yale’s Peabody Museum, completed in 1947. This 110-foot fresco depicted the progression of reptilian life across the Mesozoic Era, with dinosaurs as its centerpiece. The mural presented dinosaurs as slow-moving, cold-blooded reptiles by prevailing scientific views of the time. Zallinger’s artwork gained massive exposure when it was reproduced in Life magazine and in the popular Time-Life book series, reaching millions of households. The procession of scaly creatures in muted greens, browns, and grays became the standard vision of prehistoric life for an entire generation of Americans. The plodding dinosaurs in this mural would later serve as the perfect embodiment of what would be challenged by the coming “Dinosaur Renaissance.”

The Cold-Blooded Paradigm in Scientific Thought

The portrayal of dinosaurs as essentially reptilian wasn’t merely artistic license—it reflected the scientific consensus that persisted well into the 1960s. Paleontologists generally classified dinosaurs as cold-blooded reptiles, albeit exceptionally large ones, with physiological limitations similar to modern lizards and crocodilians. This scientific paradigm dictated how artists depicted dinosaurs, reinforcing an image of lumbering, sluggish creatures requiring warm environments to function. The perceived cold-bloodedness explained the tail-dragging posture seen in most dinosaur art, as scientists believed dinosaurs lacked the energy and muscular strength to hold their tails aloft. This physiological assumption influenced everything from their depicted behavior to their skin texture and color. Scientists rarely questioned these assumptions until the work of maverick paleontologists like Robert Bakker and John Ostrom began challenging orthodoxy in the late 1960s.

Burian, Parker, and the Persistence of the Reptilian Model

Throughout the mid-20th century, illustrators Zdeněk Burian and Neave Parker produced influential dinosaur reconstructions that reinforced the reptilian paradigm while reaching international audiences. Burian’s stunningly detailed paintings for Czech paleontologist Josef Augusta’s books depicted dinosaurs with scaly skin and generally conservative postures, though with somewhat more vitality than earlier works. Parker’s illustrations for the British Museum and numerous publications similarly portrayed dinosaurs as essentially giant lizards, complete with wrinkled, elephantine skin and dragging tails. Both artists’ work was widely reproduced in dinosaur books throughout the 1950s and 1960s, cementing the scaly lizard image in the minds of children worldwide. Despite their artistic differences, both Burian and Parker worked within the scientific framework of their time, visualizing dinosaurs through a distinctly reptilian lens that would soon face serious challenges.

The Dinosaur Renaissance: Bakker’s Artistic Revolution

The traditional image of dinosaurs began facing serious scientific challenges in the late 1960s and early 1970s with what would become known as the “Dinosaur Renaissance.” Paleontologist Robert Bakker, uniquely talented as both scientist and artist, created revolutionary dinosaur illustrations depicting these animals as active, dynamic, and potentially warm-blooded creatures. His kinetic sketches showed dinosaurs running, leaping, and fighting with tails held high off the ground and bodies in active poses. Bakker’s illustrations directly challenged the lumbering lizard paradigm, supporting his controversial theories about dinosaur physiology and behavior. His 1968 article “The Superiority of Dinosaurs” and subsequent work presented visual evidence for an energetic lifestyle inconsistent with cold-blooded metabolism. Bakker’s dual role as scientist-artist allowed him to directly translate new theories into compelling visual representations that began reshaping public perception.

Jurassic Park and the Popular Awakening

The release of Steven Spielberg’s “Jurassic Park” in 1993 represented the definitive moment when modern dinosaur science reached mainstream consciousness, revolutionizing public perception virtually overnight. The film’s dinosaurs, created through groundbreaking special effects, incorporated many aspects of contemporary paleontological thinking, including upright postures, active behaviors, and social interactions. For the first time, millions of viewers saw Velociraptors hunting in coordinated packs and Tyrannosaurus moving at frightening speeds. The film famously popularized the theory that birds are descended from dinosaurs, with its velociraptors described as “six-foot turkeys.” While the film still depicted dinosaurs with primarily scaly skin (largely missing the emerging evidence for feathers), it demolished the sluggish reptile stereotype that had dominated previous generations’ understanding. The commercial success of Jurassic Park made scientifically informed dinosaur representations the new standard for popular media.

The Missing Feathers: Evidence Overlooked

Even as dinosaur posture and behavior were being reimagined, one crucial aspect of dinosaur appearance remained overlooked in popular representations well into the 1990s and 2000s: feathers. The first feathered dinosaur fossils emerged from China’s Liaoning Province in the mid-1990s, revealing conclusively that many theropod dinosaurs possessed feathery coverings. Despite mounting evidence, artists, filmmakers, and toy manufacturers continued depicting dinosaurs with exclusively scaly skin. This resistance stemmed partly from commercial considerations—scaly dinosaurs were more marketable, “monstrous” and distinct from birds—and partly from the visual inertia of established dinosaur imagery. Even the scientifically consulted Jurassic Park sequels resisted adding feathers to their Velociraptors despite overwhelming evidence that the real animals possessed them. This represents perhaps the most significant recent disconnect between dinosaur science and popular representation, one that persists in many contexts even today.

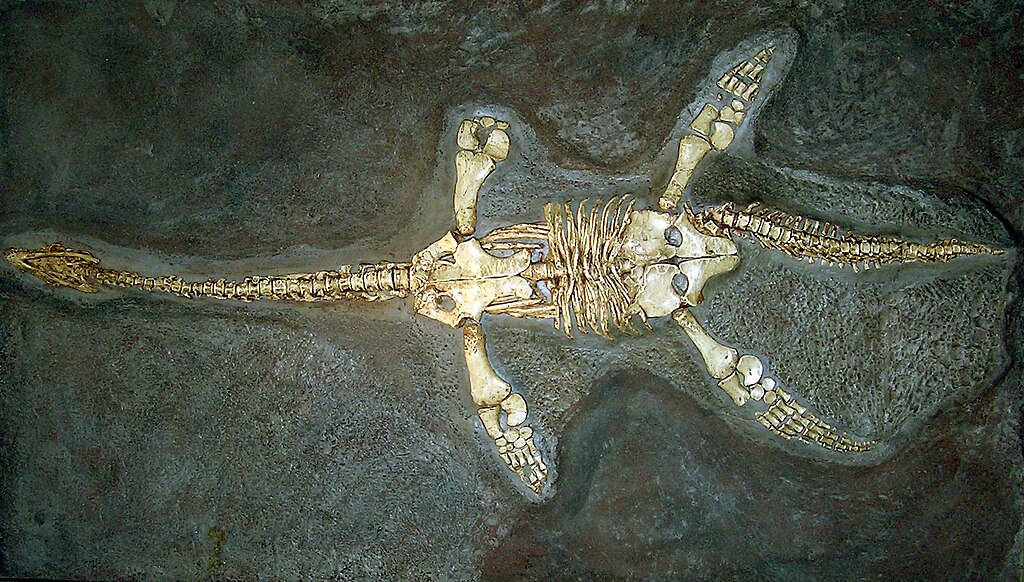

Museums: From Outdated Displays to Modern Representations

Natural history museums, once the primary perpetuators of the “dinosaurs as scaly lizards” paradigm, have undergone dramatic transformations in their dinosaur exhibits over recent decades. Many institutions maintained outdated dinosaur displays well into the 1980s and 1990s, featuring tail-dragging skeletons and accompanying artwork depicting sluggish reptilian creatures. The American Museum of Natural History’s dramatic renovation of its dinosaur halls in the 1990s marked a turning point, with skeletons remounted in active poses and new murals showing energetic, socially complex animals. Similar renovations followed at major museums worldwide, replacing outdated dioramas and illustrations with scientifically current representations. Modern museum displays now frequently include feathered dinosaur models, dynamic skeletal mounts, and interactive elements explaining the evidence for current interpretations. These institutional changes have been crucial in reshaping public understanding, though the transformation remains ongoing at smaller or less-funded institutions.

Children’s Books: The Slow Evolution of Dinosaur Imagery

Children’s dinosaur books represent a fascinating case study in the persistence of outdated dinosaur imagery, as many continued depicting dinosaurs as scaly, tail-dragging creatures well into the 1990s. These publications frequently recycled older illustrations or commissioned new art that mimicked established visual traditions, perpetuating inaccurate representations for new generations. The commercial pressure to create dinosaurs that matched children’s expectations—largely formed by existing books and toys—created a self-reinforcing cycle of scientific inaccuracy. Even as more scientifically informed books began appearing in the 1980s and 1990s, the market remained flooded with publications showing demonstrably outdated dinosaur depictions. This particularly affected school libraries, where dinosaur books might remain in circulation for decades despite containing thoroughly obsolete information. The transition to accurate dinosaur portrayals in children’s literature has been gradual rather than revolutionary, creating a generational overlap in contradictory dinosaur images.

Paleoart as Scientific Communication

The evolving representation of dinosaurs highlights the crucial role of paleoart as a form of scientific communication, bridging specialized research and public understanding. Unlike many scientific fields where photographs or direct observation can convey discoveries, paleontology relies heavily on artistic reconstruction to translate fossil evidence into comprehensible visuals. This dependency creates unique challenges, as artistic traditions and conventions can sometimes override scientific accuracy. Modern paleoartists like Mark Witton, Emily Willoughby, and Julius Csotonyi collaborate closely with scientists, basing their work directly on fossil evidence and comparative anatomy rather than previous artistic depictions. Contemporary paleoart increasingly incorporates technical knowledge of biomechanics, ecosystem relationships, and animal behavior alongside traditional artistic skills. The field has developed methodological approaches like phylogenetic bracketing—inferring unpreserved features by examining a fossil species’ closest living relatives—to create reconstructions with scientific rigor beyond mere artistic impression.

Digital Media and the Democratization of Dinosaur Imagery

The internet and digital technology have fundamentally transformed how dinosaur imagery is created and disseminated, challenging the monopoly once held by museum displays, books, and films. Social media platforms now allow paleontologists to share new findings and their visual implications directly with the public, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. Digital artists can rapidly incorporate breaking paleontological discoveries into new reconstructions, updating dinosaur appearances almost in real-time as new evidence emerges. Online paleoart communities subject reconstructions to peer review and scientific scrutiny, identifying inaccuracies and outdated features. This democratization has accelerated the replacement of the “scaly lizard” paradigm with more scientifically accurate representations, though it has also created an information environment where scientifically rigorous and completely fanciful dinosaur imagery circulates simultaneously. For consumers of dinosaur media, this requires new forms of visual literacy to distinguish between art based on evidence and pure speculation.

The Future of Dinosaur Representation

As we look toward the future of dinosaur imagery, the gap between scientific understanding and popular representation continues to narrow, though complete convergence remains elusive. Advanced technologies like 3D modeling, biomechanical simulation, and digital sculpting now allow for unprecedented precision in reconstructing dinosaur appearance and movement based on fossil evidence. Research into preserved skin impressions, pigmentation, and soft tissues continues providing new insights that challenge established visual conventions. The cultural persistence of certain dinosaur images—particularly the iconic Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor of Jurassic Park—creates tension between updated scientific models and commercially successful representations. The increasing recognition of dinosaurs as the ancestors of modern birds continues reshaping our visual understanding, with feathers, complex behaviors, and vibrant coloration replacing the monochromatic, scaly creatures of previous generations. Future dinosaur art will likely continue this trajectory toward greater biological realism while maintaining the wonder and charisma that have made these extinct animals so compelling to the public imagination.

Conclusion

The story of dinosaur representation reminds us that scientific visualization is never neutral—it always operates within artistic traditions, commercial pressures, and cultural expectations. The scaly, sluggish dinosaurs that dominated 20th-century imagery weren’t simply mistakes but reflections of the scientific understanding and artistic conventions of their time. As our knowledge continues evolving, so too will our visual conception of these extraordinary animals that dominated Earth for over 150 million years. The journey from the tail-dragging lizards of yesterday’s museums to the feathered, active creatures of contemporary paleoart demonstrates science’s capacity for self-correction and the power of art to shape our understanding of the natural world—even when that world has been extinct for 66 million years.