Picture this: Earth, 252 million years ago, was a wasteland that would make Mars look hospitable. The planet had just survived the most catastrophic extinction event in its history, wiping out nearly 96% of marine life and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates. Yet from this apocalyptic landscape, something remarkable was stirring. While tiny dinosaur ancestors scrambled for survival in the shadows, other extraordinary creatures were beginning to reclaim the devastated world. This was the Early Triassic period—a time when life hung by a thread, but refused to let go.

The Great Dying’s Devastating Legacy

The Permian-Triassic extinction event, often called “The Great Dying,” had transformed Earth into an alien world. Volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia had pumped massive amounts of carbon dioxide and toxic gases into the atmosphere, creating a greenhouse effect that pushed global temperatures to deadly extremes. Ocean acidification killed off coral reefs and countless marine species, while on land, forests withered and died under the relentless heat.

What remained was a planet stripped bare of its biodiversity. The few survivors found themselves in a world where the rules of life had completely changed. Competition was fierce, resources were scarce, and the climate was unpredictable. This wasn’t just an extinction—it was a complete reset of life on Earth.

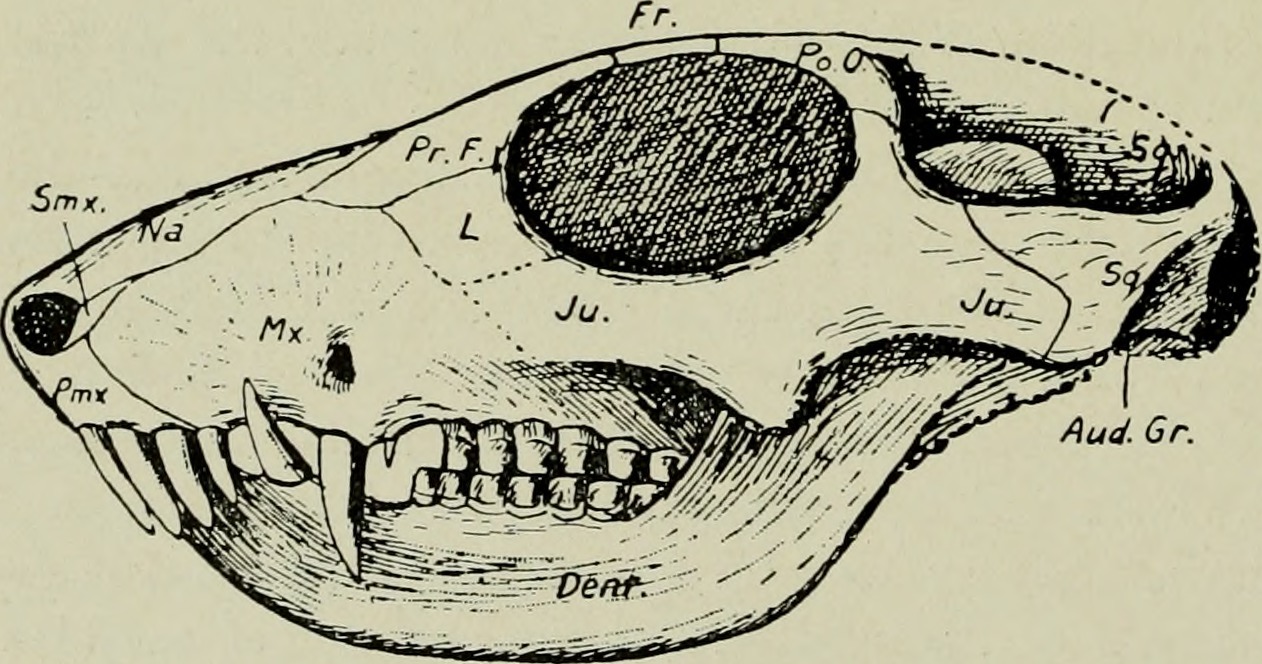

A World Dominated by Therapsids

In this harsh new reality, dinosaurs were nowhere to be found among the dominant players. Instead, mammal-like reptiles called therapsids ruled the Early Triassic landscape. These weren’t the massive predators you might imagine—most were relatively small, adaptable creatures that had managed to survive the great catastrophe. The dicynodont Lystrosaurus became so successful that it made up about 90% of all land vertebrates in some regions, earning it the nickname “the disaster taxon.”

These therapsids possessed several advantages that helped them thrive in the post-extinction world. Many had efficient metabolisms that allowed them to survive on limited food resources, while others had developed burrowing abilities that provided protection from the extreme climate. Their success was so complete that they essentially owned the planet for the first few million years of the Triassic.

The Rise of Archosaurs

While therapsids dominated the immediate aftermath of the extinction, a new group was quietly gaining ground. Archosaurs—the group that would eventually give rise to dinosaurs, crocodiles, and pterosaurs—began to emerge as serious competitors. These early archosaurs were still relatively small and unspecialized, but they possessed something crucial: adaptability.

One of the most significant early archosaurs was Euparkeria, a small, agile predator that lived in what is now South Africa. Though only about three feet long, this creature displayed many of the features that would later make dinosaurs so successful. Its efficient breathing system and improved limb structure gave it advantages over its therapsid competitors, setting the stage for the archosaur revolution that would follow.

Marine Recovery and New Ocean Rulers

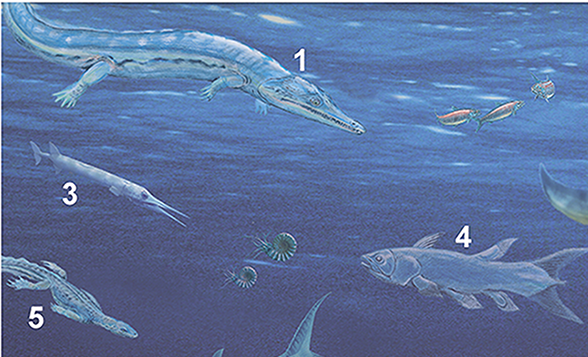

The oceans of the Early Triassic were graveyards filled with the shells of countless extinct species. Yet life found a way to bounce back, though it took time. The first marine communities to recover were simple ones, dominated by small mollusks, brachiopods, and primitive fish. These “disaster fauna” were hardy generalists that could survive in the harsh, oxygen-poor waters that characterized the early Triassic seas.

As conditions slowly improved, more complex marine ecosystems began to emerge. Early marine reptiles like the ichthyosaurs started their evolutionary journey, though they were still far from the dolphin-like giants they would later become. The first nothosaurs also appeared, beginning the lineage that would eventually produce the massive plesiosaurs of later periods.

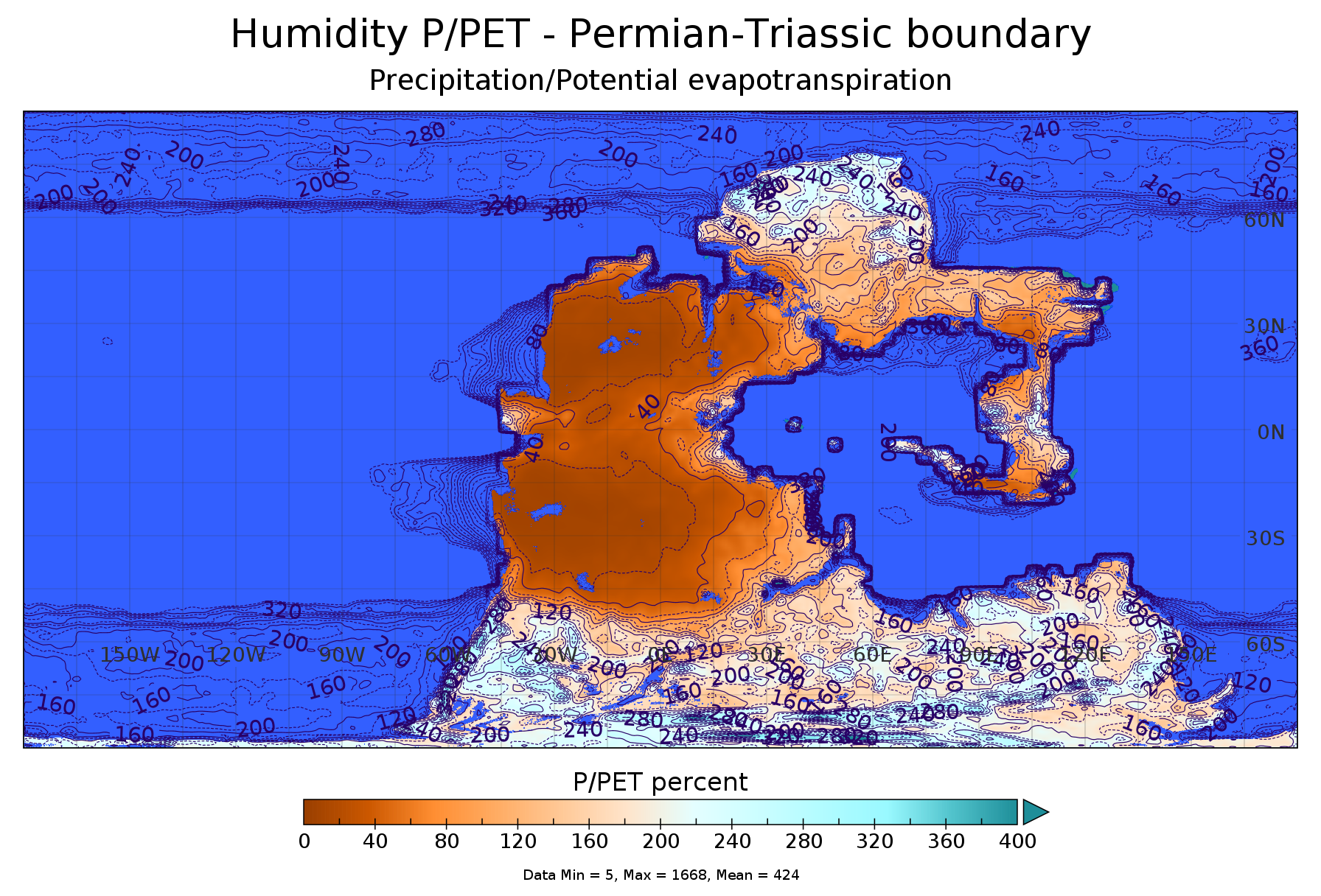

Climate Chaos and Extreme Weather

The Early Triassic climate was a nightmare of extremes that would challenge even the most adaptable organisms. Global temperatures soared to levels not seen before or since, with some estimates suggesting that equatorial regions may have been uninhabitable for complex life. The polar regions, normally frozen, became warm enough to support forests, creating a world with minimal temperature gradients from pole to equator.

This climate chaos wasn’t just about heat—it was about instability. Massive seasonal variations, unpredictable weather patterns, and frequent droughts made survival a constant challenge. Only the most flexible and resilient species could adapt to these rapidly changing conditions. The climate during this period was so extreme that it took millions of years for stable ecosystems to establish themselves.

Plant Life’s Slow Recovery

The terrestrial plant communities that had dominated the Permian period were completely shattered by the extinction event. Vast forests of seed ferns and early conifers had been reduced to scattered remnants, leaving behind a world of barren landscapes and simplified plant communities. The few surviving plants were mostly small, hardy species that could tolerate the harsh conditions.

Ferns and horsetails became the dominant vegetation in many areas, creating landscapes that looked more like modern wetlands than the diverse forests of earlier periods. These simple plant communities couldn’t support the complex food webs that had existed before the extinction, forcing animals to adapt to a world with limited and often poor-quality food sources.

The recovery of plant diversity was frustratingly slow, taking millions of years to approach pre-extinction levels. This sluggish recovery had a domino effect on animal evolution, as the lack of diverse plant communities limited the types of herbivores that could survive and thrive.

The First Dinosaur Ancestors

Somewhere in this chaotic world, the very first dinosaur ancestors were taking their tentative steps toward evolutionary success. These early dinosauromorphs were small, often bipedal creatures that bore little resemblance to the giants that would later dominate the planet. Creatures like Lagerpeton and Marasuchus were only about the size of a house cat, but they possessed the fundamental body plan that would eventually evolve into dinosaurs.

These early dinosaur relatives faced intense competition from the established therapsids and the emerging archosaurs. They survived by being generalists—able to eat a variety of foods and adapt to changing conditions. Their small size was actually an advantage in this resource-limited world, as they required less food and could hide from larger predators.

What’s remarkable is that these humble beginnings would eventually lead to the most successful group of land vertebrates in Earth’s history. But during the Early Triassic, they were just another group of small reptiles struggling to survive in a hostile world.

Volcanic Nightmares and Toxic Skies

The Early Triassic period was punctuated by continued volcanic activity that made life even more challenging. The Siberian Traps, the massive volcanic province responsible for the end-Permian extinction, continued to spew lava and toxic gases for hundreds of thousands of years into the Triassic. These eruptions created a feedback loop of environmental destruction that prevented rapid recovery.

The atmosphere during this time was a toxic cocktail of carbon dioxide, sulfur compounds, and other volcanic gases. Acid rain was common, and the high CO2 levels created a greenhouse effect that pushed global temperatures to extremes. The volcanic ash blocked sunlight, creating periods of cooling that alternated with the greenhouse warming, making climate even more unpredictable.

Animals had to evolve mechanisms to deal with these toxic conditions. Some developed improved respiratory systems, while others evolved behaviors that helped them avoid the worst effects of the polluted environment. The constant environmental stress acted as a powerful selective pressure, favoring only the most adaptable species.

The Emergence of New Predator-Prey Relationships

The simplified ecosystems of the Early Triassic forced the evolution of new predator-prey relationships. With fewer species overall, each organism had to be more flexible in its feeding habits. Predators couldn’t specialize in hunting specific prey species because biodiversity was so low—instead, they had to be opportunistic hunters capable of taking whatever was available.

This led to the evolution of some unusual feeding strategies. Many predators became scavengers, feeding on the abundant carrion left behind by the mass extinction. Others developed the ability to switch between hunting and scavenging depending on conditions. The intense competition for food resources drove rapid evolution in both predators and prey.

The lack of large herbivores meant that plant-eating animals had to be highly efficient at extracting nutrients from poor-quality vegetation. This led to the evolution of more complex digestive systems and behaviors that maximized nutrient intake from limited food sources.

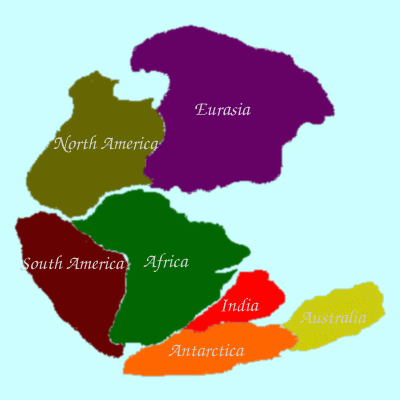

Continental Drift and Changing Landscapes

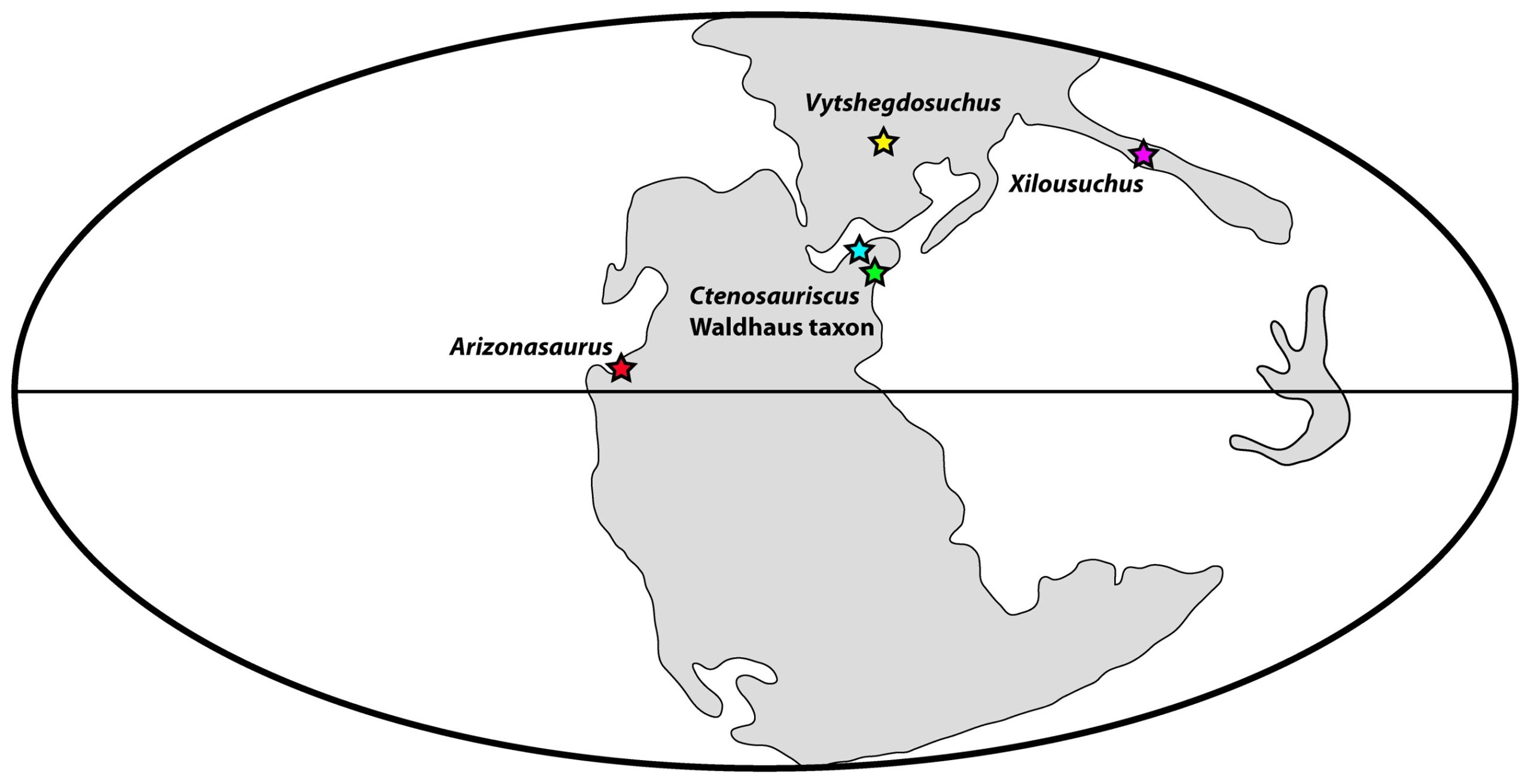

During the Early Triassic, the supercontinent Pangaea was beginning to show signs of the rifting that would eventually break it apart. This continental configuration created unique climatic conditions and geographic barriers that influenced the evolution and distribution of life. The interior of Pangaea was a vast desert, while the coastal regions experienced monsoon-like conditions.

These changing landscapes created isolated populations of animals that evolved in different directions. The geographic isolation helped prevent the spread of diseases and allowed for the evolution of distinct regional fauna. As the continents slowly began to separate, new ocean basins formed, creating opportunities for marine life to diversify and evolve.

The changing geography also affected ocean currents and climate patterns, creating new environmental pressures that drove evolution in unexpected directions. Mountains rose and fell, rivers changed course, and new habitats emerged, providing opportunities for surviving species to expand and diversify.

Underground Survivors and Burrowing Adaptations

One of the most successful survival strategies during the Early Triassic was going underground. Many animals developed burrowing abilities that allowed them to escape the harsh surface conditions and find more stable environments below ground. These underground refuges provided protection from temperature extremes, toxic gases, and predators.

The most famous example is Lystrosaurus, which survived the mass extinction partly because of its ability to dig extensive burrow systems. These burrows provided not only shelter but also access to underground water sources and plant roots. The burrowing lifestyle became so successful that it influenced the evolution of many other Early Triassic animals.

Underground ecosystems developed their own unique characteristics, with specialized predators and prey adapted to life in the dark. These subterranean communities were often more stable than surface ecosystems, providing a refuge where life could persist during the worst environmental conditions.

The Seeds of Future Dominance

Despite their humble status during the Early Triassic, the ancestors of dinosaurs were already developing the key innovations that would eventually make them the dominant land vertebrates. Improved respiratory systems, more efficient metabolism, and better locomotion were evolving in small, unremarkable creatures that few would have predicted would inherit the Earth.

The archosaur lineage was also developing the upright posture and improved limb structure that would give dinosaurs their competitive advantage. These early innovations were subtle but significant, providing small advantages that would compound over millions of years of evolution. The stage was being set for the Middle and Late Triassic periods, when dinosaurs would finally begin their rise to dominance.

What’s fascinating is that these future rulers of the planet were learning their survival skills in one of the most challenging environments in Earth’s history. The harsh conditions of the Early Triassic served as a training ground that would prepare them for their eventual success.

Recovery’s Slow Rhythm

The recovery of life during the Early Triassic was frustratingly slow compared to recoveries from other mass extinctions. It took nearly 10 million years for biodiversity to begin approaching pre-extinction levels, and even then, the ecosystems that emerged were fundamentally different from what had come before. This sluggish recovery was due to the severity of the extinction and the continued environmental stress from ongoing volcanic activity.

The pace of recovery varied dramatically between different environments and regions. Marine ecosystems generally recovered faster than terrestrial ones, partly because the ocean provided more stable conditions and buffering against climate extremes. Some regions remained essentially lifeless for millions of years, while others began showing signs of recovery within a few hundred thousand years.

This slow recovery had profound implications for evolution. The extended period of low diversity and environmental stress created unique evolutionary pressures that shaped the development of all major animal groups. The lessons learned during this difficult period would influence the course of evolution for the rest of the Mesozoic Era.

Legacy of the Underdogs

The Early Triassic period teaches us that evolutionary success isn’t always about being the biggest or strongest—sometimes it’s about being the most adaptable. The small, unassuming creatures that survived this period of crisis went on to become the ancestors of some of Earth’s most successful animal groups. Their ability to endure hardship and adapt to changing conditions was more valuable than size or strength.

This period also demonstrates the incredible resilience of life itself. Even after the worst extinction event in Earth’s history, life found ways to survive, adapt, and eventually flourish. The diversity we see in modern ecosystems can be traced back to the survivors of this catastrophic period, who refused to give up in the face of seemingly impossible odds.

The story of the Early Triassic reminds us that in nature, as in life, the underdog sometimes wins. The tiny dinosaur ancestors struggling for survival in this hostile world had no idea they were destined to rule the planet for over 160 million years. Their success came not from dominance, but from persistence, adaptability, and the remarkable ability of life to find a way forward even in the darkest of times. What other “underdogs” might be quietly preparing for their moment in the sun?