The discovery of a significant fossil, whether it’s a T. rex skull or an ancient hominid, represents a crucial piece of our planet’s history. However, the journey these specimens take from ground to museum display often travels through murky ethical waters. When prestigious institutions purchase fossils with questionable provenance, it raises profound questions about accountability, cultural heritage, and scientific integrity. The problem extends beyond simple ownership disputes—it encompasses issues of national heritage, scientific access, and the commodification of irreplaceable natural history. This complex ethical dilemma forces us to ask: When museums buy stolen fossils, who bears the ultimate responsibility?

The Global Black Market for Fossils

The illicit fossil trade represents a multi-million-dollar global industry that operates in the shadows between legitimate scientific collection and outright theft. Unlike artifacts covered by clear archaeological protection laws, fossils often exist in regulatory gray areas in many countries, making them vulnerable to exploitation. Particularly in fossil-rich regions with limited enforcement resources like Mongolia, Morocco, and parts of South America, poachers can extract specimens with relative ease. The financial incentives are substantial—a complete T-Rex skeleton might sell for millions at auction, while even smaller specimens can command prices that dwarf the annual income of residents in source countries. This black market creates a pipeline where fossils are illegally excavated, smuggled across borders with falsified documentation, and eventually “laundered” through a series of transactions until they appear legitimate enough for high-end buyers, including prestigious museums.

Legal Frameworks and Their Limitations

The legal protections for fossils vary dramatically worldwide, creating inconsistent standards that traffickers readily exploit. The United States, through the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act of 2009, prohibits collecting fossils from public lands without permits, while countries like Mongolia declare all fossils national property regardless of where they’re found. However, these regulations face significant enforcement challenges. Many fossil-rich regions lack the resources to monitor remote dig sites effectively. Furthermore, the international nature of fossil trafficking means specimens cross multiple jurisdictions, each with different standards of evidence and prosecution priorities. Once a fossil has passed through several transactions, proving its illegal origin becomes increasingly difficult, especially when documentation has been altered or fabricated. This regulatory patchwork creates convenient loopholes that allow institutions to maintain plausible deniability about a specimen’s questionable origins.

The Museum’s Dilemma

Museums face genuine ethical conflicts when presented with scientifically valuable specimens of uncertain provenance. On one hand, these institutions exist to preserve and study important natural history specimens for public benefit and scientific research. When confronted with a rare or scientifically significant fossil, museum curators may justify acquisition by arguing that institutional protection is preferable to leaving the specimen in private hands where it might remain unstudied. Additionally, competitive pressures between institutions create incentives to acquire notable specimens that attract visitors and prestige. However, these justifications increasingly conflict with ethical standards that have evolved in museum practices. By purchasing questionable fossils, museums may inadvertently fuel market demand for more illegally excavated specimens, perpetuating a destructive cycle. This tension between scientific opportunity and ethical responsibility creates genuine institutional dilemmas without easy solutions.

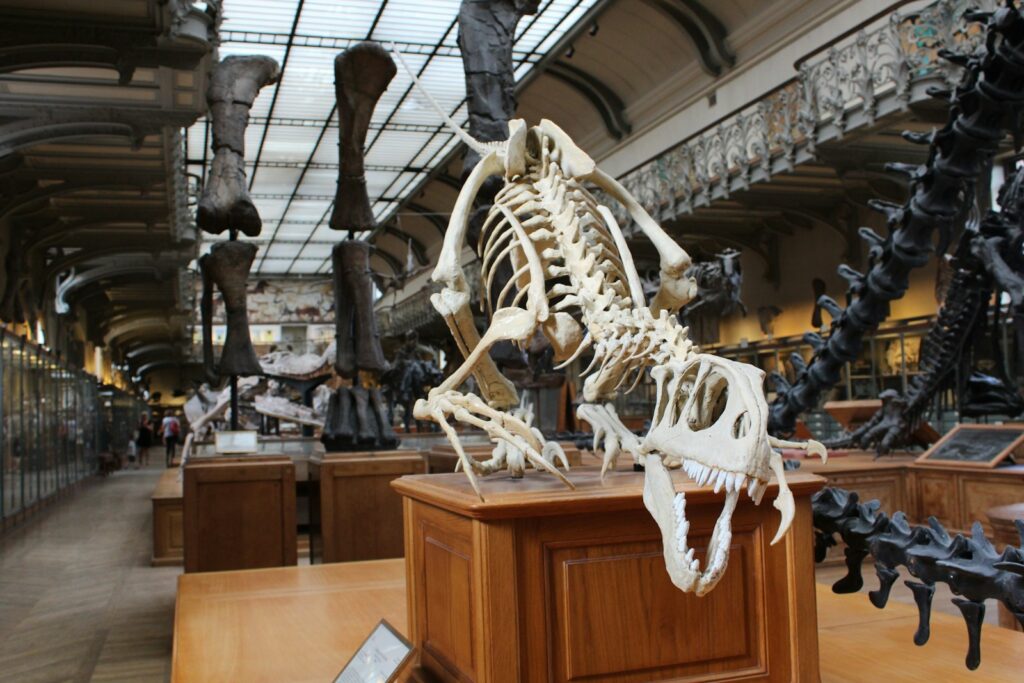

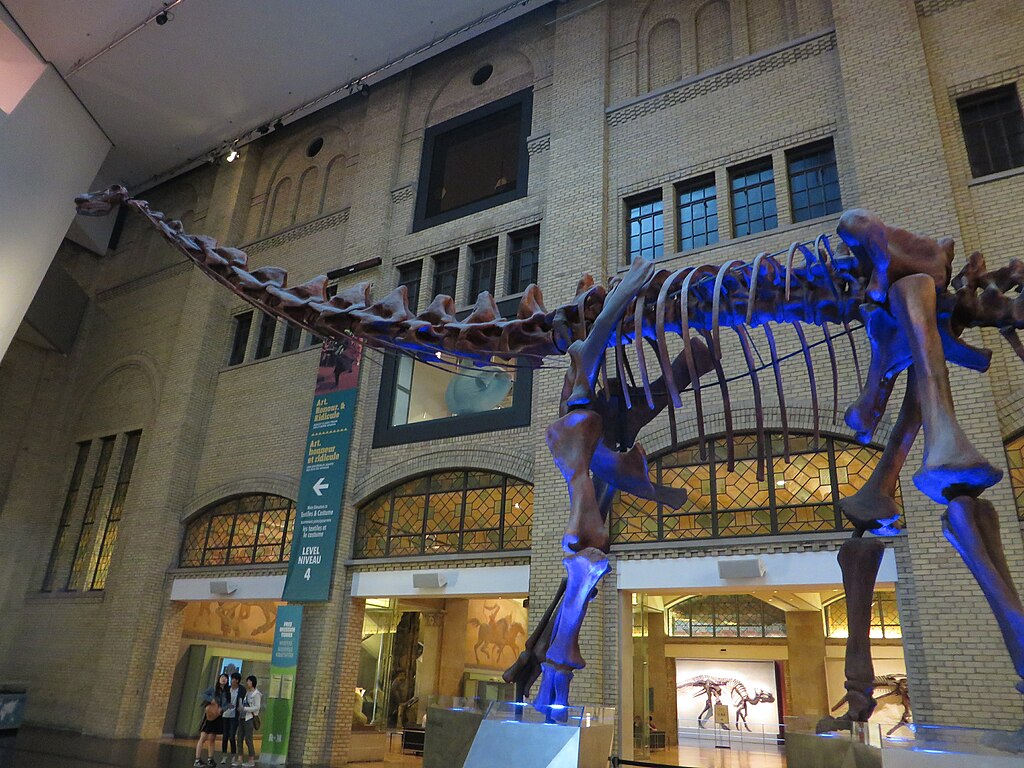

Notable Cases of Controversial Acquisitions

Several high-profile cases have brought the issue of questionable fossil acquisitions to public attention. Perhaps most famously, the Field Museum’s 1997 purchase of “Sue,” a remarkably complete T. rex skeleton, for $8.36 million came after complex legal battles over ownership rights. More recently, in 2012, federal authorities seized a Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton (a close T. rex relative) that was about to be auctioned in New York after experts identified it as having been illegally exported from Mongolia. The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County faced criticism for displaying a specimen called “Tinker,” a juvenile Tyrannosaurus, which some experts believe was commercially collected from federal lands. The American Museum of Natural History’s acquisition of multiple Mongolian dinosaur specimens in the early 20th century would be considered illegal under today’s standards, raising questions about repatriation. These cases illustrate how even prestigious institutions with significant resources for provenance research have become entangled in fossil acquisition controversies.

The Scientific Cost of Illegal Collection

When fossils are illegally excavated, crucial scientific information is permanently destroyed. Professional paleontologists document precise details about a fossil’s position, surrounding geological context, and associated specimens—data that provides critical insights about ancient environments, behaviors, and evolutionary relationships. Amateur excavators and commercial collectors typically prioritize extracting marketable specimens quickly, often using destructive methods that damage both the fossils and their contextual information. Without proper documentation of exactly where and how a specimen was discovered, scientists lose valuable data that might help understand extinct ecosystems and evolutionary patterns. This destruction of context represents an irreversible loss to science that goes beyond the physical specimen itself. Even when illegally obtained fossils eventually reach scientific institutions, these gaps in provenance information significantly diminish their research value, making proper collection methods as important as the specimens themselves.

Due Diligence and Acquisition Policies

Responsible museums have increasingly adopted rigorous acquisition policies to avoid purchasing illicitly obtained specimens. These protocols typically require comprehensive documentation of a fossil’s discovery location, excavation permits, export authorizations, and complete ownership history. The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology’s ethics guidelines explicitly discourage member institutions from acquiring specimens without clear legal provenance. Some museums now employ dedicated provenance researchers who specifically investigate potential acquisitions for red flags such as incomplete documentation, suspicious price increases between transactions, or connections to known problematic dealers. Many institutions also require approval from ethics committees before proceeding with significant acquisitions. Despite these precautions, determining legitimate provenance remains challenging, especially for specimens discovered decades ago when documentation standards were less stringent. The most ethical institutions now recognize that declining a questionable acquisition, despite its scientific value, may be necessary to uphold professional standards.

The Culpability of Private Collectors

Private fossil collectors represent a crucial link in the chain that connects illegal excavation to institutional acquisition. Wealthy individual collectors have driven market prices to unprecedented heights, with specimens like Stan the T-Rex selling for $31.8 million in 2020, creating powerful financial incentives for fossil poaching. Unlike museums, private collectors rarely face public accountability for their acquisitions and often operate with less transparency regarding provenance research. Some private collectors view themselves as temporary stewards who will eventually donate specimens to museums, potentially laundering problematic fossils through charitable gifts that may come with tax benefits. However, not all private collecting is problematic—many collectors work closely with scientists, follow legal collection protocols, and contribute valuable specimens to research. The distinction between responsible collectors who document findings properly and those who purchase questionable specimens without scrutiny remains critical to understanding this complex market dynamic.

Indigenous Rights and Cultural Heritage

The fossil trade frequently intersects with indigenous rights and cultural heritage claims in ways that complicate ethical considerations beyond legal ownership. For many indigenous communities, particularly in North America, Australia, and parts of Asia, fossils represent more than scientific specimens—they hold cultural and spiritual significance connected to creation stories and ancestral lands. The Sioux tribes of South Dakota, for instance, view dinosaur fossils found on their territories as culturally significant items connected to their spiritual traditions. When museums acquire fossils removed from indigenous lands without consultation or consent, they perpetuate colonial patterns of appropriation. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples establishes the principle that indigenous communities should have control over cultural heritage items found on their territories, creating a framework that challenges traditional scientific ownership models. Progressive institutions have begun developing collaborative relationships with indigenous communities, establishing consultation protocols for specimens from tribal lands.

Repatriation Challenges and Solutions

When museums discover they possess illegally obtained fossils, the repatriation process presents significant logistical, financial, and diplomatic challenges. The first obstacle often involves determining the rightful owner, particularly when specimens were collected decades ago from regions whose national boundaries have since changed. Additionally, museums must consider whether source countries have adequate facilities to properly conserve and study returned specimens—a genuine concern that can nonetheless become a paternalistic justification for retention. The financial implications of repatriation are substantial, including not just shipping costs for fragile specimens but also potential loss of donor support from those who funded the original acquisition. Despite these challenges, successful repatriations have occurred, such as the return of numerous dinosaur specimens to Mongolia following U.S. court cases confirming their illegal export. Innovative approaches include creating replicas for the returning institution, establishing joint research programs, or developing traveling exhibition arrangements that acknowledge source country ownership while maximizing global scientific access.

The Role of Source Countries

Countries rich in fossil resources face complex challenges in protecting their paleontological heritage while balancing economic development needs. Nations like Morocco, China, and Brazil possess extraordinary fossil resources but often lack sufficient funding for comprehensive site monitoring and enforcement. Some countries have developed innovative programs that train residents as site guardians, providing sustainable employment while protecting scientific resources. Others have established legal frameworks for controlled commercial collection with export permits and profit-sharing arrangements that benefit local communities. Mongolia, for example, has partnered with international institutions to train domestic scientists while establishing strict export prohibitions. However, corruption remains a significant challenge in some regions, where officials may facilitate illegal exports in exchange for bribes. Source countries increasingly assert sovereignty over their paleontological heritage not just through prohibitions but by developing domestic scientific capacity and museum infrastructure that creates sustainable local benefits from fossil discoveries.

Ethical Acquisition Alternatives

Museums seeking to expand their collections without participating in problematic markets have developed several ethical alternatives to purchasing fossils of questionable origin. Many institutions now prioritize field expeditions conducted under their supervision with proper permits and scientific protocols, ensuring complete documentation and legal compliance from excavation through export. Collaborative partnerships with institutions in fossil-rich countries represent another ethical approach, where specimens might remain in their country of origin but research is conducted jointly, with findings and replicas shared internationally. Some museums have established policies to accept only donated specimens that meet strict provenance requirements rather than making market purchases. Additionally, innovative technologies, including high-resolution 3D scanning and printing, enable institutions to create remarkably detailed replicas that serve educational purposes without requiring ownership of original specimens. These approaches demonstrate that scientific advancement and public education need not depend on participating in potentially unethical fossil markets.

The Responsibility of Academic Publishers

Scientific journals and academic publishers occupy a crucial gatekeeping position in determining which fossils enter the legitimate scientific record. When journals publish studies based on potentially looted specimens, they provide academic legitimacy that can increase market value and incentivize further illegal collection. Recognizing this responsibility, several prominent journals, including Nature, Science, and the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, have strengthened their ethics policies to require authors to confirm legal collection and export of specimens described in their papers. Some journals now require detailed provenance information as supplementary material before accepting manuscripts. However, implementing these policies presents challenges, as editors typically lack the resources to independently verify provenance claims. Additionally, rejection of papers featuring important specimens with questionable origins creates tension between scientific knowledge advancement and ethical standards. Despite these challenges, publication gatekeeping represents one of the most effective pressure points for encouraging ethical fossil acquisition throughout the entire collection chain.

The Future of Ethical Fossil Collection

The path toward more ethical fossil acquisition practices requires coordinated effort across multiple stakeholders in the paleontological community. Digital technologies offer promising tools for improving provenance tracking, with proposals for blockchain-based systems that could create immutable records of fossil discoveries and transfers. Public education about the scientific and cultural costs of illegal fossil trafficking can help reduce market demand for problematic specimens. International agreements similar to the UNESCO Convention on Cultural Property could establish consistent standards for fossil protection across national boundaries. Scientific institutions are increasingly recognizing that ethical considerations must take precedence over acquisition opportunities, even when this means declining scientifically valuable specimens. As museums face greater public accountability regarding collection practices, professional standards continue to evolve toward more stringent provenance requirements. The most promising developments involve collaborative relationships between source countries, scientific institutions, local communities, and ethical private collectors working together to preserve paleontological heritage while advancing scientific understanding.

Conclusion

The question of responsibility when museums acquire stolen fossils reveals a complex web of accountability extending from individual collectors to global institutions. While museums have traditionally been viewed as beneficial custodians of natural history, this perspective must evolve to acknowledge the ethical implications of acquisition practices. Responsibility ultimately lies with every participant in the fossil journey—from field collectors who must document discoveries properly, to dealers who verify provenance, to institutions that establish rigorous acquisition standards. As our understanding of scientific ethics advances, the paleontological community continues to develop more thoughtful approaches to balancing scientific access with respect for national heritage and indigenous rights. By acknowledging this shared responsibility, we can work toward a future where important fossil discoveries benefit science without perpetuating exploitative practices that damage both cultural heritage and the scientific information these irreplaceable specimens contain.